Abstract

This chapter discusses how state and regional institutional considerations can affect the enactment of both mergers and acquisitions (M&As) and corporate social responsibility (CSR). Institutional factors have been explored in previous scholarships separately for M&As and CSR. This chapter joins the two domains in an institutionally embedded global perspective. We additionally draw on complementary global strategy, strategic intent, and transnationalism perspectives to understand M&A-CSR conduct and stakeholder engagement. As firms internationalize via acquisitions, varying national and regional practices intermix and influence CSR initiatives differentially. As state and regional institutions transform [through] participation in global markets, institutionalized practices within firms adapt to new market pressures and in response to stakeholder interests and environmental concerns.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Institutional theory

- Acquisition program

- CSR program

- Global strategy

- Strategic intent perspective

- Transnationalism

- Economic development level

- International expansion

1 Introduction

In this chapter, we address how state and regional institutional considerations can affect both mergers and acquisitions (M&As) and corporate social responsibility (CSR ). A multiplicity of institutional factors such as those related to currency stability, profit repatriation, and financial regulations impact whether and how M&As, and particularly international M&As, can occur. For example, many Chinese firms have listed on US, UK, and Hong Kong stock exchanges to boost visibility to investors and access to capital markets, which can in turn facilitate cross-border acquisitions. Similarly, firms in the Arabian Gulf region have listed on increasingly robust regional exchanges, as well as sometimes on the major established exchanges, to augment international acquisition opportunities involving target firms from developed markets. The scrutiny of and requirements for financial disclosures for firms internationalizing from developing into developed markets can occur concomitant with a deeper scrutiny and encouragement of humanitarian business and environmental practices (Matten & Crane, 2005).

The aforementioned examples of institutionalized financial factors have involved outreach by emerging market multinational companies (EMNCs) onto external stock exchanges. Institutional isomorphism also predicts evolution toward developed-country institutional standards within developing markets. State and regional institutions can transform—at least somewhat—to promote participation by emerging-market firms in global markets. Likewise, institutionalized practices within firms can also adapt to new market pressures and expectations concerning responsiveness to stakeholder interests and environmental concerns. We posit that various aspects of a CSR program related to health, education, employment assurances, and disaster assistance could evolve in tandem with an international acquisition program. The CSR program would then reflect institutional considerations in various countries where an MNC/EMNC does business. These considerations could influence both philanthropic outreach and product and services delivery to the spectrum of stakeholders.

Institutional factors have been explored separately in M&As and CSR. This chapter joins the two domains of institutional theory deployment within a global perspective. This perspective encompasses national and regional practices carrying over into new domains as firms internationalize via acquisitions and become more international in outlook through social responsibility and sustainability initiatives. We use complementary theoretical lenses to examine the wellsprings of M&A and CSR interconnections and explore the implications for organizational transformation attendant on the dual pursuit of M&As and CSR. This theory-implications-transformation approach enables us to obtain deeper insights into CSR, acquisitions, and the institutional context.

We first examine institutional theory and discuss M&A and CSR factors separately and then together, tracing the trajectory of extant scholarship and providing perspectives on and new insights into the joint domain of analysis. We then explore the implications of national and regional institutional forces as experienced by firms engaged in the preliminary phases of internationalizing and then globalizing. We study the implications for internationalization via acquisitions as well as the implications for CSR and sustainability initiatives from both global and local perspectives. Finally, we note emergent pressures in the transformation of national and regional institutions as firms enter global markets, and also the parallel transformation of practices within firms in response to a spectrum of stakeholder interests.

2 Institutional Theory in CSR and M&As

A variety of theoretical approaches within institutionalism has heightened our understanding of key factors such as state and organizational rules, regulations, and procedures. Some of these institutional factors are in the financial arena, while others relate to areas of statutory and regulatory concern as well as norms, traditions, and behaviors. For instance, globalizing firms must contend with institutional incompatibilities arising from varieties of capitalism, transitions from various forms of socialism to more market-driven economies, and the challenges of dealing with differing business environments encountered during international expansion. Such factors can affect M&As and CSR, both separately and jointly, in organizations in general and in internationalization situations in particular. We examine the M&A and CSR institutional scenarios separately and then together within a variety of national contexts.

2.1 Institutional Theory and Factors in M&As

Multiple institutional stances have furthered our comprehension of M&As from a global perspective and as a mechanism of international expansion. Institutional theory highlights cross-border M&A as strategies helpful for (a) surfacing competing institutional logics between varieties of capitalism and a more state-influenced organization of markets, (b) navigating institutional transition to more market-driven economies, and (c) gaining legitimacy and an economic foothold in new institutional environments.

A segment of the literature has long argued that multinational firms expanding through acquisitions have taken advantage of institutional elements of their home markets, enabling them to build strategic strengths that they then leverage in their competition against MNCs from diverse markets. Typically, this dynamic has been seen as advantaging firms originating from environments with stronger and more stable institutional infrastructure. Nevertheless, this dynamic has also been argued to advantage EMNCs emanating from home bases with greater institutional voids. These voids can include not only the lack of regulatory, health, and educational infrastructure but also, for instance, the absence of financial intermediaries facilitating transactions between buyers and sellers. Dealing with institutional voids has, almost counterintuitively, assisted EMNCs by providing them with an advantageous bootstrapping mentality in the competition against developed market multinationals (Khanna & Palepu, 2006). EMNCs acquiring firms in developed economies markets and then doing business in those markets have been seen to not only survive but thrive (Stucchi, 2012).

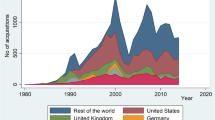

Cross-border acquisitions bring MNCs from a wide range of countries into closer competition in popular markets. National and regional institutional factors then intermingle at global crossroads. For instance, international acquisitions by EMNCs from Africa provide a compelling example of the challenges and benefits of confronting institutional voids and reconciling differential institutional contexts in the drive for international expansion (Ellis, Lamont, Reus, & Faifman, 2015). For the emerging markets of China, institutional theory deepens the understanding of target selection in international M&As when the dominant coalition derives more from an older socialist-grounded versus a newer market-driven orientation (Greve & Zhang, 2017). The competing institutional logics from varying influences on strategic activity illuminate the national origin and market power of the targets selected, as noted by Greve and Zhang (2017). Emerging-market firms from formerly socialist countries can be more likely to internationalize to the West and to acquire larger firms when influenced by a more market-oriented dominant coalition in the acquiring firm. Not only market capabilities but also an awareness of the importance of institutional shifts in nations transitioning from more state-controlled to more market-driven economies have influenced the success of developed-country MNCs making acquisitions in emerging markets such as Russia, India, and China (Li, Peng, & Macaulay, 2013). Not surprisingly, the organizational ambidexterity facilitating these economic shifts has also facilitated innovative capabilities development in M&As (Park & Meglio, 2019). Acquiring firms from both developed and developing markets benefit from understanding the nature of the economic and institutional transitions into the target firms’ home markets.

Overall, acquisitions can assist firms from both developed and developing economies in not only gaining a market foothold but also in acquiring legitimacy in the new institutional environment of any recently entered country (Held & Berg, 2015). Legitimacy in this context pertains to both internal and external perceptions of the authority and appropriateness of the organization and its right to exist, function, and flourish in the focal business environment (DeJordy & Jones, 2008).

2.2 Institutional Theory and Factors in CSR

A variety of institutional and neo-institutional theoretical factors come into play in the design and implementation of national, international, and global CSRs. These factors pertain to seeking legitimacy, interrelating state and other institutional actors, and reconciling the boundaries between business and society. Specifically, institutional theory has been applied in efforts to understand CSR as a mode of economic governance taking over from the failure of state institutions to promote social welfare in liberal-market economies (Brammer, Jackson, & Matten, 2012). As a mode of economic governance, CSR could manifest, for instance, in the launching of community initiatives (Beddewela & Fairbrass, 2016) to counteract institutional voids at the state level by offering health, educational, and housing infrastructure-related services to local residents, ensuring fair labor practices, and taking initiatives toward protecting the natural environment. Institutional approaches to CSR can also mean syncretizing institutional theory, stakeholder perspectives, and legitimacy practices toward understanding corporate motivations for CSR as well as how and why CSR, even from the same organization, varies from country to country (Fernando & Lawrence, 2014).

Institutional theory and neo-institutional theory, pertaining particularly to organizations and their incumbents, can help illuminate CSR evolution and practices in global and national domains. Organizations can adopt CSR programs to simultaneously relate to state and local actors and establish legitimacy on a global stage. Firms can use corporate community initiatives as part of an outreach to governmental actors, to supplement institutionalized state-level programs, and mediate at the boundary between business and society. This type of integrated approach facilitates an understanding of CSR as a mode of economic governance stepping in to help preserve societal health, educational, and welfare standards, even amidst any shortcomings of state institutions in liberal-market or coordinated-market economies. Multiple stakeholders, including employees, customers, and community residents, are advantaged while the firm reifies its social commitments and gains legitimacy. Institutional theory then interrelates with stakeholder perspectives and legitimacy considerations to heighten our understanding of the corporate motivations for and variations among CSR practices across national contexts.

Firms needing to be seen as legitimate—that is, valid and appropriate—can enact CSR programs adapted to the needs and interests of local communities. In India and Brazil, where colonial influences were keenly felt until independence movements arose, separation from the colonizer did not immediately mean separation from the colonizer’s institutional structures and influences. CSR initiatives have helped in righting these influences and privileging local talent over expatriate management (Millar & Choi, 2011). In the emerging markets of the African continent, the strategic use of relationship-building language (Selmier, Newenham-Kahindi, & Oh, 2015) and a burgeoning adherence to the UN Global Compact (Williams, 2013) have counteracted the former norm of low social responsibility engagement and have assisted in CSR initiatives toward environmentally sustainable economic development. The UN Global Compact has become a new form of institutionalized structure and practice militating in favor of the symbolic and substantive adoption of CSR programs by firms around the world (Rasche, Waddock, & McIntosh, 2013). Local stakeholders benefit, and global stakeholders—including, customers, investors and suppliers, as well as interested analysts and observers—applaud. We also note that alternative explanations for firm motivation for CSR—such as leadership integrity and standard bearing and the social, cultural, and religious norms influencing a focal firm and its top management—can apply as well (Fehre & Weber, 2016). We concentrate on institutional theory as our conceptual domain due to our attention to the corporate strategic underpinnings of acquisitions and CSR.

2.3 Institutional Theory and Factors: Analysis of M&As and CSR

M&As and CSR are interrelated under the aegis of institutional theory in ways that have only recently begun to be explored. Global strategy, strategic intent, transnationalism, multicultural management, and stakeholder engagement are examples of key issues entering into the dual domain of analysis. Our explorations of these interconnections are based on current precepts and practical applications and point to future theoretical and empirical directions.

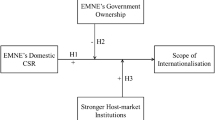

Institutional theory has long been known to predict tendencies for isomorphism (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), as organizations struggle to respond to environmental contingencies and can take cues from other (successful) organizations (Hannan & Freeman, 1977, 1984). These tendencies toward isomorphism apply even more strongly to global initiatives in an increasingly economically interdependent and digitally interconnected world (Marquis, Glynn, & Davis, 2007; Raynard, Johnson, & Greenwood, 2015), as organizations position themselves toward a transnational stance of simultaneous global integration, worldwide learning, and local responsiveness (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989). These classic and traditionally distinct perspectives on institutional theory and transnational strategy have been brought together in the context of acquisitions and CSR. Miska, Witt, and Stahl (2016) strikingly found that institutional theory tenets—explaining either tendencies toward global isomorphism or the persistence of unique national institutional characteristics—could predict global or local CSR tendencies when taken together with acquisitions and global expansion from developing into developed markets. Specifically, Miska and colleagues determined that Chinese multinationals that had already expanded to the West through M&As were more likely to have locally responsive CSR patterns. They further found that the multicultural educational and work backgrounds of top management corresponded to CSR program development in both globally integrated and nationally responsive ways. Their research intriguingly suggests a transnational (global and local) direction for future theoretical and empirical research into the institutional interconnections between M&As and CSR, as global CSR programs can be deemed reflections of isomorphic tendencies predicted by institutional theory, and locally responsive CSR programs reflect national institutional forces influencing CSR at the local level.

Institutional theory can be approached from other vantage points as well—such as from a stakeholder engagement (Selmier et al., 2015) perspective, interlinking M&As and CSR with additional enrichment to understanding. Responsiveness to multiple constituencies falls within the overall CEO leadership mandate in guiding a firm and directing expansionist maneuvers such as acquisitions (Park, 2016). Nevertheless, when CSR guidelines and ethical principles conflict with CEO ambition and perceived opportunities for a dramatic enhancement of market power, the CSR mandate may succumb to the strategic imperative for expansion (Hubbard, Christensen, & Graffin, 2017; Maak, Pless, & Voegtlin, 2016). The broader interest for stakeholder engagement is then forgotten. Only later, in the aftermath of a crisis, can the (in a sense) internal failure of CSR when confronting an aggressive expansionist and acquisition-driven agenda from within the organization be lucidly analyzed. In the case of the failed attempt by Belgian bank Fortis to acquire Dutch giant ABN AMRO as part of an acquisition consortium involving the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) and Santander (Hassan & Ghauri, 2014), an overly aggressive acquisition program felled two of the three acquirers (Fortis and RBS), and their CSR programs fell with them (Fassin & Gosselin, 2011). Stakeholders fell (in order of precedence) to strategy, ethics to opportunism, and CSR to M&As, with the financial services industry perhaps having a peculiar vulnerability to ethical breaches due to the compelling need for transparency to ensure integrity in monetary transactions (Park & Hollinshead, 2011). Institutional supports for CSR could not withstand the more controlling preferences for expansion, even when it meant overriding ethical dilemmas and contravening the organization’s own CSR guidelines (Fassin & Gosselin, 2011).

Part of the value can come from the lessons learned by merely observing. Longstanding cultural-ethical-religious traditions made for stronger support for corporate citizenship and responsibility, even in a crisis situation, in M&A and CSR practices in Japan’s banking industry (Tsuji & Tsuji, 2010). Organizational guidelines are not always as strong as deeply rooted national institutions that can hearken back to millennia-old norms of individual and collective conduct. Crises can take us back to our roots and then force us to look beyond them. The research has not indicated instances of CSR failure per se but has pointed to instances of leadership and strategic failure that have harmed CSR initiatives as a consequence.

3 Implications of Institutional and Related Theories for CSR and M&As

3.1 Implications of National and Regional Institutional Forces for the Internationalization of Firms

Internationalizing can be a way for MNCs to mitigate institutional voids in their home countries, by entering and doing business in nations and regions with better institutional infrastructure. In addition to contributing to internationalization, CSR program development and communication to stakeholders about this development can assist an MNC/EMNC in the quest for legitimacy. Part of the challenge of internationalization resides in the reconciliation of institutional differences between home and host countries. Differing institutional forces and pressures can be construed as complementary rather than as an antithetical juxtaposition. For instance, if a home country lacks a stable currency, robust financial regulations, or intellectual property protections, institutional improvements can be found abroad. As internationalizing enlarges not only the global footprint but also the global identity of the firm, legitimacy can be found, for instance, in alternative headquarters locations, listings on international stock exchanges, and even a change of firm name, or a change in the composition of the top management team or the set of languages used for everyday business communications. CSR can become part of the total solution for achieving legitimacy (Marano, Tashman, & Kostova, 2017), as CSR programs, reporting, guidelines, awards, and general recognition promote the image of a firm in the forefront of global social responsibility awareness and action.

3.2 Implications for Internationalization by Acquisition

When firms internationalize, the distance in political, economic, and knowledge systems and in developmental levels between the home and host countries has been found to impel rather than impede the momentum toward diversification into new geographic areas. These various forms of distance do not need to deter firms expanding from either an emerging or an emerged market. Cultural, financial, demographic, and geographic differences between home and host countries have been determined to have no effect on the selection of which countries to enter in internationalization decisions (Wei & Wu, 2015).

Nevertheless, the internationalization momentum benefits not just from a political, economic, and knowledge-based inspiration but also from global outreach and community initiatives around CSR (Banerjee, 2014). CSR can be part of both the motivation and integration in an acquisition. Acquisitions have become a common internationalization method, and CSR has become increasingly common alongside and even within acquisitions. It can provide a moral benchmark and vantage point for establishing legitimacy as well as a practical means of demonstrating global citizenship in an era of ongoing corporate scandals, privacy incursions, and occasional outright disregard for health and safety. CSR becomes a formidable instrument in the social responsibility repertoire of the firm. In essence, internationalization—especially for larger firms—occurs commonly through acquisitions, and acquisition programs—again, especially among larger firms—are frequently motivated and accompanied by CSR programs. The internationalization-acquisition-CSR linkage harkens back to institutional and neo-institutional theory and the institutional forces, pressures, and voids impelling firm expansion across borders while recognizing and reconciling institutional differences and benefiting from the complementarity gained by balancing those differences.

Institutional theory also relates to how deeper social, political, and organizational structures influence corporate behavior, including around internationalization, acquisitions, and CSR. As mentioned, internationalization, acquisitions—particularly cross-border acquisitions as instruments of internationalization—and CSR are interconnected through a counterbalancing of institutional differences.

Neo-institutionalism, or new institutional theory, seeks to understand how cultural precepts, social forces, and other organizations influence organizational behavior. CSR fits well within this domain as an instance of the organizational activity arising from current levels of CSR adoption. The more organizations there are that adopt CSR, the more organizations that will practice it. This isomorphism, according to institutional theory, legitimizes organizations and their pursuits. CSR can come not only from isomorphism but also, more directly, from legitimation flowing from the establishment of structures in response to institutional voids.

3.3 Implications for CSR and Sustainability Initiatives

We now turn to the question of how CSR and sustainability initiatives have been and can be influenced by the institutional substrate and by the CSR-acquisitions-institutions interconnection within an international context. We have discussed how CSR relates to both the motivation for and the integration of acquisitions. Motivation has been dealt with in terms of the mapping, managing, and measuring model addressed in earlier chapters of the book. For instance, it has been found that firms from the emerging markets of China acquire internationally with a specific strategic intent (Rui & Yip, 2008), including obtaining CSR capabilities, program development, and reputational status (Cody & MacFadyen, 2011). These aspects of CSR acquisition can be crucial for both developed- and developing-economy firms. Jormanainen and Koveshnikov (2012) advocate researching EMNCs with a focus on both macro- and micro-level factors, diverse (e.g., longitudinal and qualitative) methodologies, and emerging markets in addition to China. We heed their suggestions by taking a global perspective that embraces two of the largest emerging markets (China and India) and two large developed single markets (Europe and North America), as well as by drawing upon experiences and insights from Southeast Asia, Latin America, Africa, and the Arabian Gulf regions. We follow Morgan, Kristensen and Whitley (2001) in emphasizing the importance of understanding the diverse contextual and institutional realities in a global overview of business issues and of not falling into a highly simplified view of MNCs as convergent and stateless enterprises.

Moving from motivation to integration, we can see various manifestations of CSR that exemplify the dimensions of global integration and national responsiveness to differences in institutional voids and forces via internationalization through cross-border acquisitions. For instance, a study using data on firms from 33 countries covering 2002–2008 found that the firms were more internally than externally oriented in their CSR and sustainability initiatives (Hawn & Ioannou, 2016). Thus, firms, at least in the previous decade, tended to ‘do more and communicate less’ (Hawn & Ioannou, 2016, p. 2569). This discrepancy between the extent of CSR activities and communication about them with the outside world is oddly dissonant with the predictions of the isomorphism tenet of institutional theory and with stakeholder engagement theories, both of which would anticipate wider communication about CSR program achievements. As the study covered 33 countries spanning the US, the UK, Continental Europe, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japan, its findings pertain largely to the developed world. Investigating countries in Western Europe, Rathert (2016) found that firms adopted rights-based (vs. standards-based) CSR in labor relations to the extent that the firms sought legitimation through, and were influenced by, the existence of labor regulations. Also in the Western European context, Jackson and Apostolakou (2010) found differences in CSR implementation as predicted by institutional theory according to whether the country had a liberal-market or coordinated-market economy, with CSR programs being stronger in the former, where state-run social welfare programs were less common. Similarly, the Nordic CSR model has had its own particular trajectory, reflecting specific state, business, and cultural norms and institutions, including educational advancement and environmental protection (Gjølberg, 2010). From an emerging markets’ perspective and building on our discussion of the initiatives mentioned in China, we look at Southeast Asia and the Middle East. Beddewela and Fairbrass (2016) found that MNCs and EMNCs entering Sri Lanka launched CSR community-level initiatives to engage local institutional actors in instrumental relationship-building and advance the MNCs’/EMNCs’ business interests. Conversely, CSR in the Arabian Peninsula was seen emerging with home-country firms selectively engaging where institutional gaps/voids/absences have been found (Katsioloudes & Brodtkorb, 2007; Khan, Al-Maimani, & Al-Yafi, 2013).

4 Transformation of National and Regional Institutions as Firms Enter Global Markets

4.1 Institutional Context, Isomorphism, and Convergence

In discussing CSR, acquisitions and institutional contexts across regions such as the US, Europe, Africa, Middle East, Asia, and Southeast Asia, we have noted that institutional forces as well as stakeholder engagement, global strategy, strategic intent, and political gamesmanship have all played a role in our understanding of the M&A-M&A phenomenon. As CSR impacts both the motivation and integration phases of acquisitions and as cross-border acquisitions and international acquisition programs drive MNC/EMNC expansion into global markets, we must ask how national and regional institutions will change due to the M&A-CSR interconnection.

Institutional isomorphism theory would tend to predict a convergence between state and organizational institutional structures, but the political and social interests of sovereign nations can counteract this tendency. Even if MNCs tend toward isomorphism, they must contend with the interests of individual nations. Here, transnationalism as an approach to global strategy (Aulakh, 2007; Clark & Geppert, 2006) suggests that in counterbalancing organizational institutional convergence with national interests and divergence, CSR programs can be both globally integrated and nationally responsive. The underpinnings of the transnational duality—simultaneously global and local—have been studied in China (Miska et al., 2016). As formerly socialist economies transform into market ecosystems, in various ways, as liberal-market and coordinated-market economies exhibit their own distinctiveness, and as international acquisition programs exert transformative impacts on firms (Park, Meglio, Bauer, & Tarba, 2018), the CSR programs of global firms can reflect these institutional juxtapositions in their countries of operation and can serve stakeholders from both global and local perspectives. We explore these juxtapositions and themes further in the upcoming chapter on CSR in practice in a multinational emerging-market firm in the Arabian Gulf region.

4.2 Pillars and Foundations of Civic Society and CSR

As we have interwoven institutional theory throughout our discussion of M&As and CSR in this chapter, we also note that institutional theory has cognitive, normative, and regulative pillars that serve to support organizational striving toward social legitimacy. These pillars have applications according to what needs doing in a statutory sense (regulative), what needs to be done based on prevailing expectations (normative), and what can be determined as essential to do through strategic decision-making (cognitive) (Scott, 2014). CSR as a strategically volitional, socially expected, and in some respects—for instance, for certain labor practices and environmental care—legally required practice rests on the pillars of institutional legitimacy and also on the civil society, government, and business pillars of democratic society, as determined by scholars of political science, strategy, and organizations (Kurland, 2017). Firms and governments are each both economic and political actors subject to complementary forces and actions as expressed within the realm of CSR (Scherer & Palazzo, 2011).

While the pillars of democracy have arguably graduated to the status of received wisdom (Scherer & Palazzo, 2007), the quantity and conceptualization of the pillars of CSR have varied. Topics have ranged from the popular—economy, environment, and society (e.g., Shell, 2018)—to the more personally accountable ethics, leadership, personal responsibility, and trust (e.g., Mostovicz, Kakabadse, & Kakabadse, 2011). The fundamental economic, environmental, and social pillars of CSR have led to shorthand expressions for the ‘3-Ps’ (people, planet, and profits) based on the ‘3-Es’ (environment, economy, and social equity; Shell, 2018). Firms have their own announced pillars, varying according to the particular CSR program, but again reflecting the underlying institutional and civic pillars. Corporate governance and additional factors (Fehre & Weber, 2016) have entered into the mix, resulting in a comprehensive set of seven pillars, variously enumerated as diversity and inclusion, environmental sustainability, governance, global enrichment, organizational health, philanthropy, and supply chain integrity (US Corporate Responsibility, 2018).

A challenging factor is that CSR has intrinsically normative properties, in the sense of ethical and social responsibilities, which become even more salient when interrelated with what were previously viewed as the strictly strategic transactions of the firm, such as acquisitions. As the M&A-CSR interrelationship becomes more prominent in corporate strategic decision-making, it increasingly represents a journey unique to each firm—yet with a uniqueness reflecting an embeddedness in the global economic, environmental, and social context—as is exemplified in the upcoming chapter.

5 Conclusion

As firms internationalize via acquisitions, varying national and regional practices intermix and influence CSR initiatives differentially. As state and regional institutions transform in relation to participation in global markets, institutionalized practices within firms adapt to new market pressures and in response to stakeholder interests and environmental concerns. We also consider throughout the two remaining chapters the issues of parallel transformation in CSR practices globally in response to strategic imperatives and stakeholder interests. Such a perspective becomes consistent with the isomorphic tendencies from similar institutional pressures and with the global integration, national responsiveness, and worldwide learning dimensions of transnationalism.

References

Aulakh, P. S. (2007). Emerging multinationals from developing economies: Motivations, paths and performance. Journal of International Management, 13(3), 235–240.

Banerjee, S. B. (2014). A critical perspective on corporate social responsibility: Towards a global governance framework. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 10(1/2), 84–95.

Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. (1989). Managing across borders: The transnational solution. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Beddewela, E., & Fairbrass, J. (2016). Seeking legitimacy through CSR: Institutional pressures and corporate responses of multinationals in Sri Lanka. Journal of Business Ethics, 136(3), 503–522.

Brammer, S., Jackson, G., & Matten, D. (2012). Corporate social responsibility and institutional theory: New perspectives on private governance. Socio-Economic Review, 10(1), 3–28.

Clark, E., & Geppert, M. (2006). Socio-political processes in international management in post-socialist contexts: Knowledge, learning and transnational institution building. Journal of International Management, 12(3), 340–357.

Cody, T., & MacFadyen, K. (2011). CSR: An asset or albatross? Mergers & Acquisitions: The Dealmaker’s Journal, 46(8), 14–48.

DeJordy, R., & Jones, C. (2008). Institutional legitimacy. In S. R. Clegg & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), International encyclopedia of organization studies (p. 683). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48, 147–160.

Ellis, K. M., Lamont, B. T., Reus, T. H., & Faifman, L. (2015). Mergers and acquisitions in Africa: A review and an emerging research agenda. Africa Journal of Management, 1(2), 137–171.

Fassin, Y., & Gosselin, D. (2011). The collapse of a European bank in the financial crisis: An analysis from stakeholder and ethical perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(2), 169–191.

Fehre, K., & Weber, F. (2016). Challenging corporate commitment to CSR. Management Research Review, 39(11), 1410–1430.

Fernando, S., & Lawrence, S. (2014). A theoretical framework for CSR practices: Integrating legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory and institutional theory. Journal of Theoretical Accounting Research, 10(1), 149–178.

Gjølberg, M. (2010). Varieties of corporate social responsibility (CSR): CSR meets the “Nordic Model”. Regulation & Governance, 4(2), 203–229.

Greve, H. R., & Zhang, C. M. (2017). Institutional logics and power sources: Merger and acquisition decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 60(2), 671–694.

Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1977). The population ecology of organizations. American Journal of Sociology, 82, 929–964.

Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1984). Structural inertia and organizational change. American Sociological Review, 49, 149–164.

Hassan, I., & Ghauri, P. N. (2014). Mergers and acquisitions failures. In I. Hassan & P. N. Ghauri (Eds.), Evaluating companies for mergers and acquisitions (pp. 57–74). Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.

Hawn, O., & Ioannou, I. (2016). Mind the gap: The interplay between external and internal actions in the case of corporate social responsibility. Strategic Management Journal, 37(13), 2569–2588.

Held, K., & Berg, N. (2015). Liability of emergingness of emerging market multinationals in developed markets: A conceptual approach. In M. Marinov (Ed.), Experiences of emerging economy firms (pp. 6–31). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hubbard, T. D., Christensen, D. M., & Graffin, S. D. (2017). Higher highs and lower lows: The role of corporate social responsibility in CEO dismissal. Strategic Management Journal, 38(11), 2255–2265.

Jackson, G., & Apostolakou, A. (2010). Corporate social responsibility in Western Europe: An institutional mirror or substitute? Journal of Business Ethics, 94(3), 371–394.

Jormanainen, I., & Koveshnikov, A. (2012). International activities of emerging market firms. Management International Review, 52(5), 691–725.

Katsioloudes, M. I., & Brodtkorb, T. (2007). Corporate social responsibility: An exploratory study in the United Arab Emirates. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 72(4), 9–20.

Khan, S. A., Al-Maimani, K. A., & Al-Yafi, W. A. (2013). Exploring corporate social responsibility in Saudi Arabia: The challenges ahead. Journal of Leadership, Accountability and Ethics, 10(3), 65–78.

Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. G. (2006). Emerging giants. Harvard Business Review, 84(10), 60–69.

Kurland, N. B. (2017). Accountability and the public benefit corporation. Business Horizons, 60(4), 519–528.

Li, Y., Peng, M. W., & Macaulay, C. D. (2013). Market–political ambidexterity during institutional transitions. Strategic Organization, 11(2), 205–213.

Maak, T., Pless, N. M., & Voegtlin, C. (2016). Business statesman or shareholder advocate? CEO responsible leadership styles and the micro-foundations of political CSR. Journal of Management Studies, 53(3), 463–493.

Marano, V., Tashman, P., & Kostova, T. (2017). Escaping the iron cage: Liabilities of origin and CSR reporting of emerging market multinational enterprises. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(3), 386–408.

Marquis, C., Glynn, M. A., & Davis, G. F. (2007). Community isomorphism and corporate social action. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 925–945.

Matten, D., & Crane, A. (2005). Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 166–179.

Millar, C., & Choi, C. (2011). MNCs, worker identity and the human rights gap for local managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 104, 55–60.

Miska, C., Witt, M. A., & Stahl, G. K. (2016). Drivers of global CSR integration and local CSR responsiveness: Evidence from Chinese MNEs. Business Ethics Quarterly, 26(3), 317–345.

Morgan, G., Kristensen, P. H., & Whitley, R. (Eds.). (2001). The multinational firm: Organizing across institutional and national divides (pp. 1–26). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mostovicz, E. I., Kakabadse, A., & Kakabadse, N. K. (2011). The four pillars of corporate responsibility: Ethics, leadership, personal responsibility and trust. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 11(4), 489–500.

Park, K. M. (2016). Leadership, power and collaboration in international mergers and acquisitions: Conflict and resolution. In A. Risberg, D. R. King, & O. Meglio (Eds.), The Routledge companion to mergers and acquisitions (pp. 177–195). Oxon: Routledge.

Park, K. M., & Hollinshead, G. (2011). Logics and limits in ethical outsourcing and offshoring in the global financial services industry. Competition & Change: The International Journal of Political Economy, 15(3), 177–195.

Park, K. M., & Meglio, O. (2019). Playing a double game? Pursuing innovation through ambidexterity in an international acquisition program from the Arabian Gulf Region. R&D Management, 49(1), 115–135.

Park, K. M., Meglio, O., Bauer, F., & Tarba, S. (2018). Managing patterns of internationalization, integration, and identity transformation: The post-acquisition metamorphosis of an Arabian Gulf EMNC. Journal of Business Research, 93, 122–138.

Rasche, A., Waddock, S., & McIntosh, M. (2013). The United Nations Global Compact: Retrospect and prospect. Business & Society, 52(1), 6–30.

Rathert, N. (2016). Strategies of legitimation: MNEs and the adoption of CSR in response to host-country institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(7), 858–879.

Raynard, M., Johnson, G., & Greenwood, R. (2015). Institutional theory and strategic management. In M. Jenkins, V. Ambrosini, & N. Mowbray (Eds.), Advanced strategic management: A multi-perspective approach (pp. 9–34). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rui, H., & Yip, G. S. (2008). Foreign acquisitions by Chinese firms: A strategic intent perspective. Journal of World Business, 43(2), 213–226.

Scherer, A. G., & Palazzo, G. (2007). Globalization and corporate social responsibility. In A. Crane, A. McWilliams, D. Matten, J. Moon, & D. Siegel (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility (pp. 413–431). New York: Oxford University Press.

Scherer, A. G., & Palazzo, G. (2011). The new political role of business in a globalized world: A review of a new perspective on CSR and its implications for the firm, governance, and democracy. Journal of Management Studies, 48(4), 899–931.

Scott, W. R. (2014). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Selmier II, W. T., Newenham-Kahindi, A., & Oh, C. H. (2015). ‘Understanding the words of relationships’: Language as an essential tool to manage CSR in communities of place. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(2), 153–179.

Shell. (2018). Elements of sustainability development—Environment, society and economy. Retrieved September 17, 2018, from https://www.shell-livewire.org/business-library/689/elements-of-sustainable-development-environment-society-and-economy

Stucchi, T. (2012). Emerging market firms’ acquisitions in advanced markets: Matching strategy with resource-, institution- and industry-based antecedents. European Management Journal, 30(3), 278–289.

Tsuji, M., & Tsuji, Y. (2010). The impact of the international financial standards for mergers and acquisitions on potential employees: Some Japanese evidence. Journal of International Business Research, 9, 119–131.

US Corporate Responsibility. (2018). Seven pillars of CSR—Diversity and inclusion, environmental sustainability, governance, global enrichment, organizational health, philanthropy, and supply chain integrity. Retrieved September 17, 2018, from http://uscorporateresponsibility.org/about/the-seven-pillars-of-corporate-responsibility/

Wei, Y., & Wu, Y. (2015). How institutional distance matters to cross-border mergers and acquisitions by multinational enterprises from emerging economies in OECD countries. In M. Demirbag & A. Yaprak (Eds.), Handbook of emerging market multinational corporations (pp. 111–136). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Williams, O. F. (2013). Corporate social responsibility: The role of business in sustainable development. New York: Routledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Park, K. (2019). CSR, Acquisitions, and Institutional Context: Spanning the Globe. In: Strategic Decisions and Sustainability Choices. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05478-6_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05478-6_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-05477-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-05478-6

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)