Abstract

Taking action in the entrepreneurial context is fraught with uncertainty, risk, affective responses, and time pressures. Each of these elements impacts entrepreneurs’ evaluative abilities and behaviour. This chapter examines the affective micro-foundations of entrepreneurial cognition and its impact on behaviour. Starting with recent research on mental health and entrepreneurship the chapter critically explores a number of perspectives to facilitate an understanding of the affective drivers shaping entrepreneurial behaviour. The literature on affect in the entrepreneurial context is examined, and a comprehensive conceptual framework is proposed incorporating both the antecedents and consequences of entrepreneurial affect. Specifically, fear is discussed as an operational example and the importance of attention is presented. The chapter concludes with an overview of the conceptual framework.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Entrepreneurial behaviour

- Entrepreneurial Cognition

- Entrepreneurial Emotion

- Entrepreneurial Affect

- Market-Entry

- Decision-Making

- Entrepreneurial Attention

- Affective Dissonance

1 Chapter Overview

This chapter examines the impact of affect on entrepreneurial behaviour. The chapter opens with Sect. 9.2, an introduction exploring the affective revolution taking place in the entrepreneurship literature and the impact of affect on behaviour. This is followed by Sect. 9.3, an examination of the theoretical perspectives on affect—as a trait, as a state, affect-as-infusion, and affect-as-information are discussed. Furthermore, the seemingly incongruent nature of affect, whereby seemingly opposing affective reactions can result in a similar behaviour, is presented (e.g. stress and enthusiasm are two different affective states that both result in similar behaviour, i.e. the active processing of information from the environment). Section 9.3.1 discusses the link between affect and behaviour through the mental health lens, with reference to the adaptive nature of Behavioral Inhibition System/Behavioral Approach System (BIS/BAS) and the Dark Triad (Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy). These antagonistic personalities have been linked to entrepreneurial -entry, -intention, and -behaviour. Sect. 9.3.2 explores the entrepreneurial consequences of affect through existing research on specific emotions. For instance, overconfidence prompts market-entry decisions and an underestimation of the competition, whilst negative affect can be adaptive, facilitating critical thinking, eliminating halo effects and inferential biases, which in turn reduces gullibility and increases scepticism. Section 9.3.3 highlights the philosophical roots guiding our understanding of affect, whilst Sect. 9.3.4 centres on the usefulness of both positive and negative affects. It is argued that context is crucial in explaining affective influences on behavioural outcomes.

In the latter part of the chapter, Sect. 9.3.5 touches on expected future affective states. Section 9.3.6 discusses affective dissonance across time, in particular the desire to achieve affective balance and the contrast between the positive and negative hedonic valence during present and future events. Section 9.3.7 examines a specific affective state (fear) and its impact on entrepreneurial behaviour. Section 9.3.8 explores the individual and social cognitions that shape attentional processing. Finally Sect. 9.4 presents the conceptual framework emerging from this study and the chapter culminates with Sect. 9.5, presenting the conclusions and future research directions.

2 Introduction

In the popular press, and in line with the mindfulness movement, the role of affect (in particular positive affect) in our daily lives is the topic of much discussion. The focus on affect has been mirrored in the academic literature with Baron (2008) recognizing entrepreneurship as an emotional journey. Entrepreneurial emotion is defined by (Cardon et al. 2012, p. 3) as “the affect, emotions, moods, and/or feelings – of individuals or a collective – that are antecedent to, concurrent with, and/or a consequence of the entrepreneurial process, meaning the recognition/creation, evaluation, reformulation, and/or the exploitation of a possible opportunity”. While much focus has been on positive approach-oriented affect such as optimism, confidence (Keh et al. 2002), and self-efficacy (Strobel et al. 2011), in recent years, negativeemotions have come under scrutiny with explorations of fear (Morgan and Sisak 2016; Cacciotti and Hayton 2015), grief (Shepherd and Kuratko 2009; Shepherd and Wolfe 2014), shame (Singh et al. 2015), guilt (Mandl et al. 2016) emerging, in addition to character defects such as greed (Akhtar et al. 2013) and hubris (Hayward et al. 2006).

Following this concept of the individual as an emotional being, and in a move away from the focus on generally positive and negativemood effects (Lerner et al. 2015), research on decision-making has started to pay closer attention to specific incidental emotions and their resultant appraisals (e.g. certainty and controllability). However, entrepreneurship research continues to merely “scratch the surface” as it pays close attention to mild affective states, arguing for their key importance in the entrepreneurial process (Baron 1998; Baron et al. 2012). The impact of affect on cognition has been well documented and evidenced in the organizational behaviour literature (Forgas and George 2001) and has the potential to explain a wide range of entrepreneurial behaviours (Baron 2008; Baron et al. 2011).

Entrepreneurial behaviour is readily identifiable ex post, yet understanding the cognitive antecedents is more difficult. Kirkley (2016) found four values deemed critical to the motivation and expression of entrepreneurial behaviour—independence, creativity, ambition, and daring. However, the authors argue these four values can be undermined and eroded by affect and emotion. Fear, and its impact, is one such emotional state, and it will be explored in greater detail later in the chapter, as emotions and moods are recognized as potential influencers of entrepreneurial action (Baron 1998). In this chapter, the word “affect” is used as an umbrella term to refer to both specific emotions and mood states (Baron 2008; Barsade and Gibson 2007) (see Appendix for more detail on the nuances between emotion and mood). Affect has been shown to differ in terms of two main dimensions, namely, valence (positive vs. negative) and arousal/energy (alertness or engagement vs. sleepiness or disengagement) (Russell and Barrett 1999). Yet there is evidence suggesting that these two dimensions alone do not comprehensively explain the relationship between affect and decision-making (Lerner and Keltner 2000, 2001). The conceptual framework presented at the end of this chapter sets forth affective dissonance and attention as potential additional dimensions that should be considered when exploring the link between affect and action.

Affect is critical to entrepreneurial pursuit and shapes entrepreneurial cognition. Furthermore, affect may influence entrepreneurial action in varying ways depending on the situational context. Mild affective states may have a pervasive influence on cognition and behaviour, particularly in settings that require constructive thinking and extensive use of cognitive resources (Forgas 1995). This is particularly the case when the decision-maker has to autonomously generate ideas and search beyond the given information (Fiedler 1991). Business venturing, opportunity pursuit, and market entry are inherently uncertain (McMullen and Shepherd 2006); planned action and scripts are largely missing, requiring individuals to operate with an incomplete view. Consequently, such a context enables mood to infuse entrepreneurial cognition and action (Baron 1998). Moreover, both entrepreneurial idea generation (Hayton and Cholakova 2012) and goal-setting (Delgado-García et al. 2012) are examples of constructive or generative thought processes in the course of new venture creation. Therefore individuals seeking to enter new markets are operating in an uncertain environment, with incomplete information; thus generative thought processes are required—such a confluence of factors heightens the potential importance of affect. Furthermore, the sense of identification and personal entanglement that forms between the entrepreneur and their business is powerful, as such, emotion—both positive (e.g. confidence, joy) and negative (embarrassment, grief)—influences behaviour and decision-making in the entrepreneurial context (Wolfe and Shepherd 2015; Shepherd and Kuratko 2009). Affect (positive and negative) has purpose, and this chapter intends to explore the potential impact it has on behaviour.

3 Theoretical Perspectives on Affect

Affect can be explored through the lenses of traits or states (Watson and Tellegen 1985; George 1991). Affective traits are stable tendencies to respond in affectively similar ways (positive vs. negative) to a variety of events in life (Lyubomirsky et al. 2005). Positive and negative affective traits have been shown to be related to entrepreneurial goal-setting and satisfaction (Delgado-García et al. 2012). Where behaviour is concerned, a trait approach—whether affective or not—indicates a stable personality disposition, independent of specific characteristics, whilst a state approach considers behaviour as the result of psychological processes induced by situational characteristics (Cacciotti and Hayton 2015). Trait research has been the cornerstone of early entrepreneurship research; however a small but growing number of articles examine whether entrepreneurs have a higher positive affective disposition than the general population (Baron et al. 2011; Baron et al. 2012).

State affect (affect experienced in a particular moment) has been suggested to shape entrepreneurial cognition and subsequent decision-making (Baron 1998). One way in which affect (positive and negative) can infuse our thinking is by activating affectively similar cognitive material through memory and past experiences. For instance, if an entrepreneur has failed completely in a particular course of action, that specific stumble is likely to remain connected in their mind to unpleasant or negative affect. According to the associative models of human memory (Bower 1981), it is likely that in a future situation, when the entrepreneur experiences a similar affective state, he or she will retrieve and remember information congruent with that negative feeling. For example, affectively congruent information can include recalling past financial losses or the social and personal costs attached to entrepreneurial failure. This theoretical approach has its roots in the affect-as-infusion theory (Forgas 1995), which has received extensive empirical support (Forgas 2002; Tan and Forgas 2010; Forgas 2013). A second complementary (Forgas and George 2001) way in which mood and some specific emotions (Schwarz 2002) can impact thought processes is through the affect-as-information mechanism (Schwarz and Clore 2003). This theoretical framework considers that decision-makers use their existing mood as a valid source of information to guide subsequent behaviour (Clore et al. 2001). It suggests that affect may have actual informative value—an individual assesses their affective disposition, and depending on the assigned level of importance/significance attached to the affect, they incorporate this into their evaluation of a particular opportunity (Welpe et al. 2012). Essentially, prior to acting on an opportunity, an entrepreneur’s “emotions shape the impact of the cognitive evaluation of the opportunity on the tendency to exploit it” (Welpe et al. 2012, p. 70). A positive affective state may indicate that the present environment is benign and safe, and therefore little action is needed to adapt to it (Schwarz and Clore 2003). Similarly, high-energy affects such as nervousness, stress (both negative), enthusiasm, and excitement (both positive) engage decision-makers to actively process information from their environments, whilst low-energy moods like boredom, depression (negative), contentedness, and serenity (positive) are aligned with withdrawal and low engagement (Healey and Hodgkinson 2017; Elsbach and Barr 1999).

In sum, affect is important in opportunity recognition as well as realization (Baron 1998; Goss and Sadler-Smith 2017). Positiveemotions are linked to holistic and creative thinking, whilst negativeemotions are coupled with critical and analytical information processing (Healey and Hodgkinson 2017). Based on this premise, an entrepreneur who feels in a good mood may be more willing to quickly commit to a given opportunity (potential type I error), or conversely, if in a negativemood, they may reject a promising opportunity prematurely (potential type II error) (Baron 2007). However, seemingly opposing affective dispositions (e.g. depression and serenity) can result in similar behaviour despite emerging from very different triggers.

3.1 Linking Affect and Behaviour: The Mental Health Lens

A novel lens through which to view the association between affect and behaviour is mental health. There is growing interest in the link between mental health and entrepreneurship in the popular (Bruneau 2018; Kaufman 2018; Bruder 2013) and academic (Stephan 2018; Wiklund et al. 2018) press. Wiklund et al. (2018) argue that it is context that largely determines whether particular human characteristics and behaviour can be considered functional or dysfunctional. Research on both the Behavioral Inhibition System/Behavioral Approach System (BIS/BAS) and the Dark Triad (Hmieleski and Lerner 2016; Haynes et al. 2015a; Haynes et al. 2015b; Mathieu and St-Jean 2013; Ronningstam and Baskin-Sommers 2013) explore the adaptive nature of mental disorders. Where psychopathy and BAS are present, an individual’s ability to feel fear is questionable (e.g. psychopathy); given that risk-taking is central to entrepreneurial action, a disorder such as psychopathy is arguably useful. As such it is no surprise that the Dark Triad, encompassing Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy, “an important cluster of antagonistic personalities in psychology” (Jones and Figueredo 2013, p. 521), has been tentatively linked to entrepreneurial entry (Hmieleski and Lerner 2016), entrepreneurial intention (Kramer et al. 2011), and entrepreneurial behaviour (Rauch and Hatak 2015).

Mental disorders also influence individuals’ allocation of attention to environmental stimuli in different ways (Wiklund et al. 2018). For instance, ADHD broadens individuals’ attention (Kasof 1997), which in turn can facilitate the recognition of new entrepreneurial opportunities (Shepherd et al. 2017; Wiklund et al. 2018). Autism is linked with pattern identification (Baron-Cohen et al. 2009) and dyslexia with more original thinking (Tafti et al. 2009). Individuals with bipolar disorder and ADHD experience unusually high positive affect; this can also facilitate opportunity recognition (Baron 2008; Wiklund et al. 2018). Furthermore narcissistic entrepreneurs may influence “stakeholders’ attention to opportunities for change, increase optimism regarding change, and mobilize their resources” (Wiklund et al. 2018, p. 19). The narcissists’ disposition towards working for themselves rather than working for the firm is likely to hinder stakeholder support in the long term, yet it can be adaptive to business venturing and short-term stakeholder support (Wiklund et al. 2018).

Although there is an elevated prevalence of individuals with dark characteristics engaging in business venturing, there remains a large majority that are likely to have a more rounded emotional experience. Whilst dark predispositions may be heralded as useful for entrepreneurship, overall psychologists maintain that emotions are more adaptive than maladaptive as they “provide important signals regarding the degree of fit between people and their environments, focus their attention, and enable them to react quickly to the situation at hand” (Healey and Hodgkinson 2017, p. 112). Furthermore, seemingly negative affect is not without use and the adaptive functions of mild negativemood states are recognized in the psychology literature (Forgas 2013). In summary, the mental health and entrepreneurship research stream highlights that affect (both positive and negative) can be either adaptive or maladaptive depending on the context. Furthermore, certain mental disorders are conducive to entrepreneurial behaviour, and the initiation of business venturing and the emerging research evidence this.

3.2 Entrepreneurial Consequences of Affect

In order to further explore the entrepreneurial consequences of affect, this section will explore existing research on the subject. Firstly, joy, one of the functions of joy is to detect new chances and opportunities (Carver 2003). Joy has been found to increase exploitation and magnify the relationship between evaluation and exploitation (Welpe et al. 2012). Interestingly anger has also been found to do this, thereby further highlighting that two very different affective dispositions can lead to identical outcomes.

In another vein, optimistic individuals are more likely to regard adversity as a challenge and remain confident during difficult periods. Research suggests that a biased optimistic approach at very early entrepreneurial stages may unlock motivational resources and ultimately increase performance (Bénabou 2015). This shows that even when an individual is biased by their affective disposition, it can be advantageous. However, the beneficial entrepreneurial consequences of positive affect as a stable disposition have been found to be curvilinear (Baron et al. 2012). New entrepreneurial ventures are subject to the “liability of newness” (Hannan et al. 1998), and being blinded by optimism does not negate this liability. Thus, while it is beneficial, optimism becomes less favourable if it manifests into overconfidence. Research has found support for a negative relationship between overconfidence and survival rates in nascent entrepreneurial markets (Koellinger et al. 2007). Overconfidence prompts market-entry decisions and underestimation of the competition, which has long-lasting implications for the future of a firm (Cain et al. 2015).

However, confidence and even overconfidence can be productive in the appropriate context. They result in entrepreneurial resilience in the long term and thus help reduce any negative outcomes arising from risk-taking (Hayward et al. 2010) or entrepreneurial failure (Ucbasaran et al. 2013). Overconfidence may be a natural way to cope with a difficult environment and may be more adaptive in specific situations (Bollaert and Petit 2010). Overconfidence fosters positive affect in entrepreneurial contexts (Hayward et al. 2010). This pleasant affective state, bolstered by recent success, may in turn enable individuals to more easily process information that could threaten their self-esteem (Trope and Pomerantz 1998) and potentially enhancing decision-making performance (Elorriaga-Rubio, 2018).

Where negative affect is concerned (which may arise in time-pressured, uncertain, or challenging work environments), it can promote self-defensive mechanisms and increase inward-looking responses (Ucbasaran et al. 2013). However negative affect can at times be adaptive, facilitating critical thinking (Healey and Hodgkinson 2017), and increasing scepticism (Forgas 2013). Furthermore, negative affect leads individuals to pay closer attention to external information, thus improving interpersonal effectiveness and enabling individuals to produce higher-quality persuasive arguments when necessary (Forgas 2013).

These findings highlight the adaptive nature of affect. Neither positive nor negative affect is wholly adaptive nor wholly maladaptive—each has its purpose depending on the situation at hand.

3.3 Antecedents of Affect

When considering the links between affect and behaviour in the entrepreneurship context, it is important to understand the antecedents of affect as they unfold in the entrepreneurial process.

Philosophers have frequently written about the conflict between reason andemotion as a conflict between divinity and animality (Haidt 2001). Two contributing classes of motives that bias and/or influence reasoning are relatedness motives that refer to impression management and the fluid interactions with people and coherence motives that “includes a variety of defensive mechanisms triggered by cognitive dissonance and threats to the validity of one’s cultural worldview” (Haidt 2001). Related to the latter motive is entrepreneurs’ need to safeguard a positive self-image, which may be a more influential driving force than objective, data-driven approaches to decision-making (Jordan and Audia 2012). When navigating uncertain environments, a self-enhancement motive, that is, the need to see oneself in a positive light, may be a natural reaction to psychologically cope with a highly uncertain—and thus potentially threatening—business environment (Elorriaga-Rubio, 2018).

Similarly, according to recent research on motivated beliefs of economic decision-making, individuals facing high uncertainty, such as entrepreneurs, may respond in “judgement-driven” (i.e. a motivation to do better) or “affect-driven” (i.e. a motivation to feel better) ways depending on the task at hand or the present circumstances (Bénabou 2015). Disentangling specific events and situational aspects that may trigger different affective reactions in entrepreneurs is crucial; positive and negative events from the environment (e.g. achieving funding from a business angel or failing to attain a government grant) cause different affective reactions, which will have different subsequent consequences on future entrepreneurial action (Shepherd and Patzelt 2017).

An affect-based theoretical approach to strategic decision-making, which similarly focuses on the context of high uncertainty, also differentiates between these two motivations—that is, to perform better and to feel better—and suggests that negativeemotions promote impulsive behaviour (Ashton-James and Ashkanasy 2008). Examples of such affect-driven or impulsive behaviours are emotional outbursts or violence (Ashkanasy et al. 2002). Essentially, people may respond in behaviourally different ways in order to restore the equilibrium of their affective imbalance; affect does not always help one to instrumentally adapt to the environment. Based on this theoretical perspective, particular economic events—such as performance cues from unexpected environmental jolts—will cause different emotions and moods in the decision-maker, ultimately impacting behavioural outcomes (Ashton-James and Ashkanasy 2008; Weiss and Cropanzano 1996).

Studies in economics show that humans deliberately and consistently try to avoid negative news from the environment, as a way to preserve self-esteem and regulate aversive affective states. Eil and Rao (2011) found that exposure to negative objective information—in the form of a ranking—resulted in less rational updating as compared to exposure to positive news. These findings have been corroborated by other studies (Möbius et al. 2011) that also find support for a desire to avoid direct exposure to threatening objective information. This is known as the “ostrich effect” (Karlsson et al. 2009). However, such reluctance to confront problematic situations can exacerbate rather than ameliorate them (Schulman 1989).

3.4 Instrumental and Adaptive Affective Mechanisms

Both positive and negative affective states can have a beneficial impact on cognition and assist in appropriately processing information in response to situational or task-related demands. For instance, positivemood has been related to increased mental flexibility and openness to information from the environment—even information that can be threatening to one’s self-esteem (Trope and Pomerantz 1998). Fast and heuristic reasoning and the capacity to integrate complex information are also enhanced under positive affective states (Estrada et al. 1997). Positive affect has been shown to improve creativity (Isen et al. 1985) and both firm and individual performance in entrepreneurship (Baron et al. 2011). In contrast, negative affect has been associated with effortful or analytical processing, defensiveness, alertness, and self-focused attention (Green et al. 2003). These types of highly analytical and detail-oriented approaches facilitated by a negativemood are highly valuable in some situations, such as financial decisions made by traders (Au et al. 2003). In the specific case of entrepreneurial behaviour, paying attention to negative information from the market may also be crucial in order to continuously improve customer satisfaction (Baron et al. 2011).

In addition to general affective states, discrete emotions are also important in order to successfully cope with the environment; emotions help us to cope with potential harms. Each emotion has a different core theme attached to it, which has a significant meaning for one’s well-being (Lazarus 1993). Specific emotions vary in certain cognitive appraisals that are attached to them, such as novelty, goal significance, and coping potential, among others (Ellsworth and Scherer 2003). For instance, emotions can significantly vary on certainty appraisals or “the degree to which future events seem predictable and comprehensible versus unpredictable and incomprehensible” and still have the same valence—positive or negative (Lerner and Keltner 2000). As previously mentioned, two emotions that at the surface share the same valence (i.e. positive or negative) may prompt very different behaviours. However, this concept is at odds with the predictions from the affect-as-infusion theory (Forgas 1995), as mood effects do not infuse cognition and behaviour in a mood-congruent manner—as the theory would predict. For instance, take the case of happiness and anger, two very different emotions that have different hedonic valence, positive and negative, respectively. Interestingly, it has been evidenced that both can equally lead to increased opportunity exploitation and risk-taking (Lerner and Keltner 2001).

Thus, different theories on affect, such as the affect-as-infusion model (Forgas 1995; Forgas and George 2001) and appraisal theories of discrete emotions (Lerner and Keltner 2000, 2001; Lerner et al. 2015), may yield different predictions. However, a variety of studies have supported the informative value of hedonic valence—positive or negative—and defended its importance for the study of behavioural consequences of affect (Forgas 2002; Tan and Forgas 2010). In an attempt to reconcile previous findings, it has been suggested that contextual factors, such as the cognitive demands of a particular situation or task, are key to explaining the mood-congruence versus mood-incongruence accounts (Forgas and George 2001). A study by George and Zhou (2002) found that relying on the affect-as-information heuristic, individuals in a negativemood were more creative problem-solvers than individuals in a positivemood when they scored high in clarity of feelings. The authors from this study suggested that under these specific conditions (i.e. clarity of feelings), a positivemood signed that more effort was not needed, while those in a negativemood interpreted their unpleasant mood as a sign that more effort was indeed needed. In contrast, under different conditions, positivemood may have beneficial consequences on creativity (Estrada et al. 1997), and even complement the beneficial role of negative affect on creativity (George and Zhou 2007). Essentially, context has a crucial relevance in explaining affective influences on behavioural outcomes. In the following sections, it is proposed that anticipated affect before market-entry decision may be a key contextual aspect to consider, especially as it relates to the immediate affect a decision-maker is experiencing.

3.5 The Role of Anticipated Affect

The primary focus of the study of affect in entrepreneurship has been on trait dispositions and immediate affective states. Despite the growing importance of situated cognition in entrepreneurship (Mitchell et al. 2011) and episodic affective states (Podoynitsyna et al. 2012), little attention has been paid to the way in which entrepreneurs anticipate their future affective states when deciding to enter—or not—a new market. Moreover, in line with the idea of affect-driven motives, it seems relevant to investigate the relationship between the feelings experienced in a given moment and those affective states—positive or negative—that are expected to be felt in the future, after a particular decision to enter (or not) a new market has been taken.

There are, however, some exceptions in the literature. For instance, entrepreneurial passion, an intense form of positive affect attached to entrepreneurs’ meaning and identity, involves the anticipation of an ideal future state which will potentially bring pleasant future affective states (Cardon et al. 2012). In a similar vein, it has been suggested that entrepreneurs engage in “if only…” type of counterfactual thoughts (Baron 2000), and they do so as frequently as other individuals, mostly in relation to past entrepreneurial opportunities (Markman et al. 2002). These thoughts will in turn shape future goal-directed behaviour (Bagozzi and Pieters 1998). Research has shown, moreover, that when individuals have a great amount of autonomy—as is the case of entrepreneurs—compared to situations of restricted choice, they put considerable effort into their chosen risky projects as a way to reduce potential future regret (Sjöström et al. 2017). Therefore, in principle, it is plausible to expect that entrepreneurs, prone to regretful thinking related to opportunities, would also be more cautious when contemplating risky options (Markman et al. 2002), such as market entry.

3.6 Affective Dissonance Across Time: A Situational Perspective

Entrepreneurs have been characterized as highly positive and energetic individuals, who score higher than the average population on positive affect as a trait disposition (Baron et al. 2011). Despite entrepreneurs’ predisposition to feel positive affective states, navigating in an uncertain environment with a high potential for failure is likely to promote negative affective states—both immediate and anticipated. This is especially likely to occur in the case of entrepreneurs, who have a high commitment and passion towards their businesses, and thus successes and failures related to it are likely to influence their affective states (Cardon et al. 2009; Walsh and Cunningham 2017). Thus, when deciding to enter (or not) a new market, it is expected that entrepreneurs’ will experience a variety of emotions and moods. The conceptual framework proposes that the greater the distance (in terms of positive and negative valence) between immediate and anticipated affect—in the hypothetical future, when considering to enter (or not) the market—the more likely it will be for the individual to be motivated to preserve a positive affect or alternatively restore a negative one. In other words, in these situations of high affective ambivalence, entrepreneurs will be incentivized to follow a hedonic or “affect-driven” approach whereby their self-esteem will more likely be protected. Thus, if entering a new market and exploiting a perceived opportunity is anticipated as an attractive event that will help maintain a present positive affective state or alternatively restore a negative affect, entrepreneurs may be prone to enter the market as an attempt to achieve affective balance. However, if the anticipated affect does not imply any improvement or on the contrary threatens the maintenance of an already existing positive affective state, the probability of entering the market will decrease. This contrast between the positive and negative hedonic valence and present and future events is referred to as “entrepreneurial affective dissonance”.

According to goal-framing theory (Lindenberg and Steg 2007; Lindenberg 2008), human behaviour is guided by different goals and which goal will be activated in a particular situation will depend on the present environmental cues. A hedonic goal is a desire “to improve the way one feels right now” (Lindenberg 2008). In this chapter the “hedonic goal” refers to the underlying desire that guides entrepreneurs’ behaviour in instances where the main motivation is to reduce the affective dissonance between present and future contingencies. Although a hedonic goal focuses on the present moment, prospective feelings related to a future state, such as fear, hope, and feelings related to the past, such as joy or sadness (Clore and Ortony 2000), are likely to intervene in the process of achieving the hedonic goal.

In addition to feeling good or better in the present, entrepreneurs are particularly focused on achieving strategic goals such as growing market share and/or entering new markets. Strategic goals are usually considered medium or long term (Lindenberg 2008); however, in an attempt to reduce affective dissonance, entrepreneurs may engage in impulsive behaviour in the present moment, such as entering a market too quickly. This relates to “affect-driven” motives, discussed earlier in this chapter. When entrepreneurs make fast, risky, market-entry choices without enough time to engage in more patient or economic-driven reasoning, they face the risk of being fully guided by their need to feel good. When hedonic goals are activated, individuals are willing to act on impulse (Lindenberg 2012).

These types of fast impulsive behaviours, such as taking unnecessary risks, will be more likely to emerge under negativemood states (Ashkanasy et al. 2002; Ashton-James and Ashkanasy 2008). This is coherent with prior research that has evidenced a higher sensitivity towards losses for individuals feeling positive affect (as compared to individuals in a neutral affect), which likely corresponds to an innate protective mechanism to maintain a pleasant affective state (Isen et al. 1988). Similarly, research has found that positive affect, as compared to neutral affect, reduces the chances of risk-taking in a high-risk bet, as compared to a low-risk bet (Isen and Patrick 1983). All these arguments point to the idea that entrepreneurs are not only driven by a desire to maximize earnings in the medium or long term but also may follow a hedonic goal based on moment-to-moment affect, as a way to preserve their affective well-being in relation to the fate of their ventures.

There are a variety of different ways in which entrepreneurs could restore their affective dissonance. One way would be to use different cognitive strategies, such as de-attaching oneself from a past failure (Walsh 2017). Based on the affect-as-infusion principle (Forgas 1995), past entrepreneurial failure experiences have the potential to trigger memories and thoughts related to a similarly unpleasant feeling, which influences—in a mood-congruent manner—the immediate affect felt by entrepreneurs in the present moment. Explicit cognitive strategies such as engaging in the recall of positive memories or thoughts may also be used to improve one’s aversive affective state (Erber and Erber 2000). Interestingly, previous research has found that unnecessary risk-taking following a negative affective state may be reduced by giving individuals the possibility to engage in a cognitively demanding task—which has been shown to restore negative affect (Kim and Kanfer 2009). Recently it was highlighted that behaviourally engaging in different actions may be a promising way to regulate negative affective states in entrepreneurship (Cardon et al. 2012). For instance, Kato and Wiklund (2011) find that before market entry, in the pre-launch entrepreneurial stage, entrepreneurs feel a mixture of highly positive and negative affect and thus seek affirmation from others as a way to regulate their affect.

The conceptual model presented in this chapter helps to reconcile previous contradictory evidence between affect-congruence and incongruence accounts. While positivemood may be related to overconfident patterns in entrepreneurship, such as innovation, new opportunity recognition and exploitation, and risk-taking (Baron 2008; Foo 2011), negative affect may also translate into risk-taking action, such as impulsive market entry. Overconfidence itself can be understood as an affect-driven behaviour by which affective equilibrium is restored (Blanton et al. 2001). The idea that negatively valenced affect can equally result in approach tendencies directed to restore one’s threatened affective imbalance fits well with recent research on emotion and decision-making. According to appraisal theories on emotion in entrepreneurial settings (Welpe et al. 2012; Foo 2011), equally positive or negativeemotions can trigger very different behavioural reactions (Lerner et al. 2015). Specific appraisals related to particular emotions are one way to shed light on the complexity of the relationship between affect and behaviour. However, there may be other possible contextual factors (Forgas and George 2001) that are worth understanding in relation to affective antecedents and consequences in entrepreneurship. The model presented in this chapter proposes affective dissonance as one important factor that deserves future empirical investigation. In this regard, it would be important to analyse other potential contextual factors behind the activation of hedonic versus strategic goals in market entry.

3.7 The Case of Fear

Fear is an emotional response to a perceived threat. According to Mitchell and Shepherd, “not all fear of failure is created equal” (2011, p. 196). Individuals’ responses also vary—some may respond aggressively to the threat, others avoid facing the situation as a means of protecting oneself, whilst more still become paralyzed by the situation, known as the fight-flight-freeze reaction (Kreitler 2004; Gray and McNaughton 2000). A sense of fear can be motivating and propel entrepreneurial action (Morgan and Sisak 2016); however high levels of fear are considered an avoidance-orientated emotion, which can be debilitating and corrode motivation. Fear, in particular fear of failure, impacts entrepreneurial behaviour by reducing exploitation and minimizing the relationship between evaluation and exploitation (Welpe et al. 2012). Fear of failure is the anticipation of a negative feeling; if the fear is too threatening to one’s self-esteem, and the possibility of stigma too great, entrepreneurs will avoid entering a market and putting themselves in harm’s way. Fear is a deep-rooted, evolved, primitive emotion, predating higher cognitive functions (Kish-Gephart et al. 2009) that results in avoidance behaviour; it reduces one’s ability to deal effectively with perceived threats, and it leads to pessimistic perceptions about risks and future outcomes (Lerner and Tiedens 2006; Maner and Gerend 2007; Kish-Gephart et al. 2009). When triggered, it can elicit an instant, non-conscious reaction (Öhman 2000, 2008), therefore resulting in impulse reaction rather than reasoned action. This is likely to be the case when the gap between present and anticipated affect is large.

Fear is often learned through indirect experiences such as observation and storytelling (Rachman 1990; Reiss 1980). It is a powerful emotion that influences perception, cognition, and behaviours in ways that are still underappreciated in the current literature (Kish-Gephart et al. 2009). Attention to fear in organizational life has not developed in line with the “affective revolution” that has swept through organizational research (Kish-Gephart et al. 2009; Barsade et al. 2003; Brief and Weiss 2002). Cognitive appraisal theorists argue that discrete emotions (Izard and Malatesta 1987) involve a combination of primary and secondary appraisals (Roseman and Smith 2001; Kish-Gephart et al. 2009). Whereby primary appraisal relates to the individuals’ expectation of how their current situation will change due to the perceived threat and secondary appraisal is related to their belief that the outcome of the situation is uncertain or beyond their control (Kish-Gephart et al. 2009)—the threat is regarded as greater if it is perceived as being beyond their control. Such appraisals represent the importance and meaning an individual ascribes to a given threat/situation, and they occur with and without conscious awareness (Grandey 2008).

An individual’s response to threats in the environment comprises complex sets of cognitive processes, including both the conscious and non-conscious; they may be instantaneous and considered. Perceived threats can induce a low-intensity fear (where threat is regarded as less severe and less immediate), sometimes referred to as anticipatory fear (Plutchik 2003); it increases vigilance, environmental scanning, and behaviour that includes the narrowing of attention on possible threats (Kish-Gephart et al. 2009).

3.8 Attention and Opportunity Pursuit

One final dimension that impacts an individual’s ability to identify potential entrepreneurial opportunities, impacts an individual’s affective disposition, and influences motivation is attention. The business environment provides a constant stream of competing issues vying for a decision-maker’s attention. One’s individual and social cognitions shape attentional processing, in addition to organizational provisions, such as rules, resources, norms, procedures, and structural channels. This array of tangible and conceptual scaffolds influences the distribution of decision-makers’ attention at any given time. Focusing one’s attention involves the concentration of cognitive processes on a particular issue or set of issues. However, the channelling of consciousness indirectly implies the withdrawal of attention from other aspects in order to deal effectively with the issue of concern (Ocasio 1997). The Attention-Based View suggests that attention, and its appropriate allocation to relevant activities, is the key factor in explaining why some can adapt to changes in the environment when others cannot (Tseng et al. 2011).

The two commonly acknowledged types of attention in the psychology literature are bottom-up and top-down attention, alternatively known as stimulus-driven and goal-oriented attention (Carrasco 2011; Corbetta and Shulman 2002; Pinto et al. 2013). In top-down processing (goal- or schema-driven), one is attending to a specific matter; information flows from higher to lower centres, engaging prior experiential wisdom and existing knowledge. On the other hand, with bottom-up processing (stimulus- or data-driven), one is receptive; the focus is directed by sensory stimulation that captures one’s attention (Corbetta and Shulman 2002).

Selective attention binds features of the perceptual environment into consciously experienced wholes (Treisman and Gelade 1980). There is a risk involved in only focusing on things that are relevant, because one can shut oneself off from everything else. One does not see the world as it is; rather one sees the world that one is looking for! One of the most popular takes on attention describes it as a bottleneck. According to this view, attention is the necessary mechanism that allows us to attend to the large amount of sensual input delivered to our mental apparatus. If one did not have this filter, the sheer volume of information would otherwise “overheat” the mind.

4 Attention, Affect, and Entry: A Conceptual Model

To summarize the elements presented in this chapter, and highlight their link to entrepreneurial behaviour, a conceptual model has been developed. The chapter began with an examination of affect and the different ways it can influence behaviour. Firstly, affect-as-infusion theory, which sets forth the argument that past experiences create memories, which in turn generate feelings, and these can be triggered by subsequent similar events (e.g. a business failure experience causing an entrepreneur anxiety about restarting). Secondly, affect-as-information whereby specific emotions can impact thought processes, such as an entrepreneur’s existing emotion being used as a valid source of information to guide subsequent behaviour. Thirdly, anticipated affect whereby an entrepreneur’s expected future feelings will influence their behaviour in the present day (e.g. imaging an ideal future where they successfully launch a new product could shape current behaviour in order to achieve this ideal future state). These three drivers shape an individual’s immediate affective state.

Attention is another factor, alongside affect, that impacts behaviour. For an entrepreneur to act on a particular opportunity, they must first notice and become aware of the opportunity. As previously mentioned individuals with ADHD have a broader attention span, linked to greater recognition of entrepreneurial opportunities. Attention is the channelling of consciousness, and where an entrepreneur chooses to focus their attention is the object that will in turn impact their affect. This combination of affect and attention shapes the visibility and interpretation of internal and external threats.

Affective dissonance is the distance between one’s current and anticipated affect. The greater the distance between immediate and anticipated affect, the more likely one will preserve a positive affect or alternatively restore a negative one. This is driven by the need to achieve affective balance—one’s current self must align with one’s future self to a degree, and if the distance between current self and future self is too great, then there is a desire to reduce this distance. This makes the desired future state more achievable and realistic.

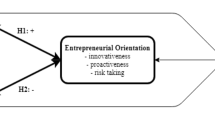

Entrepreneurial behaviour is core to our understanding of entrepreneurship, yet research progress is clouded by the fact that the majority of studies to date examine entrepreneurial behaviour through the lenses of economic rationality and for-profit venturing (Gruber and MacMillan 2017). Within the general psychology literature, the influence of affect on behaviour has long been recognized; however this link tends not to permeate into studies on entrepreneurial behaviour. Recent literature in neuroscience has identified a lower neural response to negative information in overly confident or optimistic individuals (Sharot 2012)—traits usually found in entrepreneurs. Such studies point to the idea that there is a clearly differentiated cognitive-affective mechanism that gets activated when stakes are high, primarily related to self-protective mechanisms. Figure 9.1 illustrates the way in which affect can impact behaviour using a conceptual framework. It highlights the relationships between the proposed variables and dimensions. Firstly an entrepreneur’s attention is channelled in a particular direction—due to an event, opportunity, market characteristics, and so on. The entrepreneur’s affect following identification of the event acts as a source of information (they are excited, fearful, worried), potentially triggering the affect-as-information mechanism. This affective reaction colours the event as either an opportunity or a threat, which in turn re-activates affectively similar cognitive material through memory and past experiences (affective infusion). At this point the entrepreneur is confronted with a present state of immediate affect and greater the distance (in terms of positive and negative valence) between immediate and anticipated affects—in the hypothetical future, when imagining having entered (or not) the market—the more likely it will be for them to be motivated to preserve a positive affect or alternatively restore a negative one. Thus, a key motivation, when making a market-entry decision, based on this model is the affective dissonance between present and future contingencies and a desire to reduce this dissonance.

Understanding affect enables a more encompassing picture of entrepreneurial behaviour to develop. Entrepreneurs’ affective reactions can be leveraged, as Hahn et al. (2012, p. 98) argue, “entrepreneurs should be particularly inclined to take advantage of their affective well-being to perform behaviors that benefit their businesses” (Hahn et al., 2012, p. 98). However, while some emotions are heralded as predictors of start-up behaviour (e.g. anticipated regret, Hatak and Snellman 2017), more often entrepreneurs’ behavioural responses to emotions are heterogeneous (Shepherd et al. 2014). The conceptual model presented in Fig. 9.1 enables researchers to look beyond the rudimentary emotion-behaviour link to understand the source of the emotion in relation to the individuals’ information processing, affective reaction and anticipation, and attentional focus.

“entrepreneurs should be particularly

inclined to take advantage of their affective well-being to perform behaviours that benefit

their businesses”

5 Conclusions and Future Research Direction

Entrepreneurial behaviour is easily identifiable ex post, yet understanding its antecedents is more complex. This chapter examines the antecedent role of affect on entrepreneurial cognition and behaviour. The conceptual framework highlights the various elements of affect and the way in which they influence behaviour. The chapter specifically focuses on entrepreneurial behaviour; it builds on the emerging topics from the extant entrepreneurship literature (mental health, Stephan 2018; Wiklund et al. 2018; Hmieleski and Lerner 2016; emotion, Cardon et al. 2012; failure, Walsh and Cunningham 2016) to facilitate understanding beyond the black box of entrepreneurial behaviour. Whilst affect plays an antecedent role in an entrepreneur’s behaviour, other drivers such as context, experience, and attention are necessary to consider. Future research could operationalize the proposed conceptual model. Given the heterogeneity of responses to different emotional stimuli, it would be interesting to see more experimental studies that evoke particular emotions in entrepreneurs through vignettes, music, or actual successes and stumbles and then ask them to perform particular decision-making tasks related to market entry. Such studies may also gather data on individuals’ characteristics and personality traits in order to gain a more comprehensive picture on the individual, in addition to situational affective aspects. Experiments would also help to rigorously differentiate between the effect of immediate affect and anticipated affect, in order to test if affective dissonance acts as a valid antecedent and/or moderator of entrepreneurial behaviour, such as market entry.

For instance, there are many potentially different ways in which affect can impact entrepreneurial behaviour. Affect can indeed act as an antecedent, as discussed in this chapter, but also a moderator. For example, many studies have found that overconfidence is detrimental for decision-making; however, affect may act as a moderator in this relationship, particularly in the high-uncertainty environments that entrepreneurs usually operate in. In fact, as mentioned earlier, overconfidence itself can be a way to regulate negative affective states (Blanton et al. 2001). Entrepreneurs tend to react personally to environmental cues, such as gains and losses. Positive and negative performance information may in turn affect their affective response (i.e. immediate affect). Based on the affective dissonance mechanism proposed, overconfident entrepreneurs may perform worse subsequent to a recent failure than those that feel especially happy or proud of a recent achievement. Future research along this vein, analysing affective dissonance and how entrepreneurs may react to it, deserves empirical consideration. Furthermore, it would be also interesting to explore this potential phenomenon at the team level, by analysing how entrepreneurial teams’ with high confidence in their teams’ ability to achieve a goal (collective efficacy) react to different performance information from the environment (e.g. competitors’ performance information).

At an individual level, this chapter highlights the important role affect plays in entrepreneurial decision-making and subsequent behaviour. Entrepreneurs with a vacillating nature may stymie the impact of their volatility through planning and working with more affectively balanced individuals. Furthermore, in this era where the pursuit of happiness and positive affect is central, it is necessary to appreciate the utility of negativeemotions. Negativeemotions are adaptive, pragmatic, and favourable in particular contexts; they can protect the entrepreneur from poor decision-making or hasty market entry, and this needs to be appreciated and understood. Furthermore, understanding how negativeemotion relates to anticipated affect appears to be a promising area for future research.

References

Akhtar, Reece, Gorkan Ahmetoglu, and Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic. 2013. Greed is good? Assessing the relationship between entrepreneurship and subclinical psychopathy. Personality and Individual Differences 54 (3): 420–425.

Ashkanasy, Neal M., Charmine E.J. Härtel, Wilfred J. Zerbe, N.M. Ashkanasy, W.J. Zerbe, and C.E.J. Härtel. 2002. What are the management tools that come out of this. In Managing emotions in the workplace, 285–296. Armonk: ME Sharpe.

Ashton-James, C.E., and N.M. Ashkanasy. 2008. Chapter 1. Affective events theory: A strategic perspective. In Emotions, ethics and decision-making, 1–34. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Au, Kevin, Forrest Chan, Denis Wang, and Ilan Vertinsky. 2003. Mood in foreign exchange trading: Cognitive processes and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 91 (2): 322–338.

Bagozzi, Richard P., and Rik Pieters. 1998. Goal-directed emotions. Cognition & Emotion 12 (1): 1–26.

Baron, Robert A. 1998. Cognitive mechanisms in entrepreneurship: Why and when entrepreneurs think differently than other people. Journal of Business Venturing 13 (4): 275–294.

———. 2000. Counterfactual thinking and venture formation: The potential effects of thinking about “what might have been”. Journal of Business Venturing 15 (1): 79–91.

———. 2007. Behavioral and cognitive factors in entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurs as the active element in new venture creation. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 1 (1–2): 167–182.

———. 2008. The role of affect in the entrepreneurial process. Academy of Management Review 33 (2): 328–340.

Baron, Robert A., Jintong Tang, and Keith M. Hmieleski. 2011. The downside of being ‘up’: entrepreneurs’ dispositional positive affect and firm performance. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 5 (2): 101–119.

Baron, Robert A., Keith M. Hmieleski, and Rebecca A. Henry. 2012. Entrepreneurs’ dispositional positive affect: The potential benefits–and potential costs–of being “up”. Journal of Business Venturing 27 (3): 310–324.

Baron-Cohen, Simon, Emma Ashwin, Chris Ashwin, Teresa Tavassoli, and Bhismadev Chakrabarti. 2009. Talent in autism: Hyper-systemizing, hyper-attention to detail and sensory hypersensitivity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 364 (1522): 1377–1383.

Barsade, Sigal G., and Donald E. Gibson. 2007. Why does affect matter in organizations? The Academy of Management Perspectives 21 (1): 36–59.

Barsade, Sigal, Arthur P. Brief, Sandra E. Spataro, and J. Greenberg. 2003. The affective revolution in organizational behavior: The emergence of a paradigm. Organizational Behavior: A Management Challenge 1: 3–50.

Bénabou, Roland. 2015. The economics of motivated beliefs. Revue d’économie politique 125 (5): 665–685.

Blanton, Hart, Brett W. Pelham, Tracy DeHart, and Mauricio Carvallo. 2001. Overconfidence as dissonance reduction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 37 (5): 373–385.

Bollaert, Helen, and Valérie Petit. 2010. Beyond the dark side of executive psychology: Current research and new directions. European Management Journal 28 (5): 362–376.

Bower, Gordon H. 1981. Mood and memory. American Psychologist 36 (2): 129.

Brief, Arthur P., and Howard M. Weiss. 2002. Organizational behavior: Affect in the workplace. Annual Review of Psychology 53 (1): 279–307.

Bruder, Jessica. 2013. The psychological price of entrepreneurship. Inc. Magazine (NYC, USA), May 10. https://www.inc.com/magazine/201309/jessica-bruder/psychological-price-of-entrepreneurship.html

Bruneau, Megan. 2018.7 Reasons entrepreneurs are particularly vulnerable to mental health challenges. Forbes Magazine (NYC, USA), May 10. https://www.forbes.com/sites/meganbruneau/2018/04/04/8-reasons-entrepreneurs-are-particularly-vulnerable-to-mental-health-challenges/#7aeae90d63a3

Cacciotti, Gabriella, and James C. Hayton. 2015. Fear and entrepreneurship: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews 17 (2): 165–190.

Cain, Daylian M., Don A. Moore, and Uriel Haran. 2015. Making sense of overconfidence in market entry. Strategic Management Journal 36 (1): 1–18.

Cardon, Melissa S., Joakim Wincent, Jagdip Singh, and Mateja Drnovsek. 2009. The nature and experience of entrepreneurial passion. Academy of Management Review 34 (3): 511–532.

Cardon, Melissa S., Maw-Der Foo, Dean Shepherd, and Johan Wiklund. 2012. Exploring the heart: Entrepreneurial emotion is a hot topic. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (1): 1–10.

Carrasco, Marisa. 2011. Visual attention: The past 25 years. Vision Research 51 (13): 1484–1525.

Carver, Charles. 2003. Pleasure as a sign you can attend to something else: Placing positive feelings within a general model of affect. Cognition & Emotion 17 (2): 241–261.

Clore, Gerald L., and Andrew Ortony. 2000. Cognition in emotion: Always, sometimes, or never. In Cognitive neuroscience of emotion, ed. Richard D.R. Lane, L. Nadel, G.L. Ahern, J. Allen, and Alfred W. Kaszniak, 24–61. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clore, Gerald L., Karen Gasper, and Erika Garvin. 2001. Affect as information. In Handbook of affect and social cognition, ed. J.P. Forgas, 121–144. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Corbetta, Maurizio, and Gordon L. Shulman. 2002. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 3 (3): 201.

Delgado-García, Juan Bautista, Ana Isabel Rodríguez-Escudero, and Natalia Martín-Cruz. 2012. Influence of affective traits on entrepreneur’s goals and satisfaction. Journal of Small Business Management 50 (3): 408–428.

Eil, David, and Justin M. Rao. 2011. The good news-bad news effect: Asymmetric processing of objective information about yourself. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 3 (2): 114–138.

Ellsworth, Phoebe C., and Klaus R. Scherer. 2003. Appraisal processes in emotion. In Handbook of affective sciences, ed. Richard J. Davidson, Klaus R. Scherer, and H. Hill Goldsmith, 572–595. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Elorriaga-Rubio, Maitane. 2018. The behavioral foundations of strategic decision-making: A contextual perspective. PhD Diss., Copenhagen Business School.

Elsbach, Kimberly D., and Pamela S. Barr. 1999. The effects of mood on individuals’ use of structured decision protocols. Organization Science 10 (2): 181–198.

Erber, Ralf, and Maureen Wang Erber. 2000. The self-regulation of moods: Second thoughts on the importance of happiness in everyday life. Psychological Inquiry 11 (3): 142–148.

Estrada, Carlos A., Alice M. Isen, and Mark J. Young. 1997. Positive affect facilitates integration of information and decreases anchoring in reasoning among physicians. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 72 (1): 117–135.

Fiedler, Klaus. 1991. On the task, the measures and the mood in research on affect and social cognition. In Emotion and social judgments, ed. P. Forgas, 83–104. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Foo, Maw-Der. 2011. Emotions and entrepreneurial opportunity evaluation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 35 (2): 375–393.

Forgas, Joseph P. 1995. Mood and judgment: The affect infusion model (AIM). Psychological Bulletin 117 (1): 39.

———. 2002. Feeling and doing: Affective influences on interpersonal behavior. Psychological Inquiry 13 (1): 1–28.

———. 2013. Don’t worry, be sad! On the cognitive, motivational, and interpersonal benefits of negative mood. Current Directions in Psychological Science 22 (3): 225–232.

Forgas, Joseph P., and Jennifer M. George. 2001. Affective influences on judgments and behavior in organizations: An information processing perspective. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 86 (1): 3–34.

Frijda, Nico H., and Batja Mesquita. 1994. The social roles and functions of emotions. In Emotion and culture. empirical studies of mutual influence, ed. Shinobu Kitayama and Hazel Rose Markus, 51–88. Washington: American Psychological Association.

George, Jennifer M. 1991. State or trait: Effects of positive mood on prosocial behaviors at work. Journal of applied Psychology 76 (2): 299.

George, Jennifer M., and Jing Zhou. 2002. Understanding when bad moods foster creativity and good ones don’t: The role of context and clarity of feelings. Journal of Applied Psychology 87 (4): 687.

———. 2007. Dual tuning in a supportive context: Joint contributions of positive mood, negative mood, and supervisory behaviors to employee creativity. Academy of Management Journal 50 (3): 605–622.

Goss, David, and Eugene Sadler-Smith. 2017. Opportunity creation: Entrepreneurial agency, interaction, and affect. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 12 (2): 219–236.

Grandey, Alicia A. 2008. Emotions at work: A review and research agenda. In Handbook of organizational behavior, ed. Cary Cooper and Julian Barling, 235–261. London: Sage.

Gray, Jeffrey A., and Neil McNaughton. 2000. The neuropsychology of anxiety. New York: Oxford University Press.

Green, Jeffrey D., Constantine Sedikides, Judith A. Saltzberg, Joanne V. Wood, and Lori-Ann B. Forzano. 2003. Happy mood decreases self-focused attention. British Journal of Social Psychology 42 (1): 147–157.

Gruber, Marc, and Ian C. MacMillan. 2017. Entrepreneurial behavior: A reconceptualization and extension based on identity theory. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 11 (3): 271–286.

Hahn, Verena C., et al. 2012. Happy and proactive? The role of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being in business owners’ personal initiative. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (1): 97–114.

Haidt, Jonathan. 2001. The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review 108 (4): 814.

Hannan, Michael T., Glenn R. Carroll, Stanislav D. Dobrev, and Joon Han. 1998. Organizational mortality in European and American automobile industries part I: Revisiting the effects of age and size. European Sociological Review 14 (3): 279–302.

Hatak, Isabella, and Kirsi Snellman. 2017. The influence of anticipated regret on business start-up behaviour. International Small Business Journal 35 (3): 349–360.

Haynes, Katalin Takacs, Michael A. Hitt, and Joanna Tochman Campbell. 2015a. The dark side of leadership: Towards a mid-range theory of hubris and greed in entrepreneurial contexts. Journal of Management Studies 52 (4): 479–505.

Haynes, Katalin Takacs, Matthew Josefy, and Michael A. Hitt. 2015b. Tipping point: Managers’ self-interest, greed, and altruism. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 22 (3): 265–279.

Hayton, James C., and Magdalena Cholakova. 2012. The role of affect in the creation and intentional pursuit of entrepreneurial ideas. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (1): 41–68.

Hayward, Mathew L.A., Dean A. Shepherd, and Dale Griffin. 2006. A hubris theory of entrepreneurship. Management Science 52 (2): 160–172.

Hayward, Mathew L.A., William R. Forster, Saras D. Sarasvathy, and Barbara L. Fredrickson. 2010. Beyond hubris: How highly confident entrepreneurs rebound to venture again. Journal of Business Venturing 25 (6): 569–578.

Healey, Mark P., and Gerard P. Hodgkinson. 2017. Making strategy hot. California Management Review 59 (3): 109–134.

Hmieleski, Keith M., and Daniel A. Lerner. 2016. The dark triad and nascent entrepreneurship: An examination of unproductive versus productive entrepreneurial motives. Journal of Small Business Management 54 (S1): 7–32.

Isen, Alice M., and Robert Patrick. 1983. The effect of positive feelings on risk taking: When the chips are down. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 31 (2): 194–202.

Isen, Alice M., Mitzi M. Johnson, Elizabeth Mertz, and Gregory F. Robinson. 1985. The influence of positive affect on the unusualness of word associations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48 (6): 1413.

Isen, Alice M., Thomas E. Nygren, and F. Gregory Ashby. 1988. Influence of positive affect on the subjective utility of gains and losses: It is just not worth the risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55 (5): 710.

Izard, Carroll E., and Carol Z. Malatesta. 1987. Perspectives on emotional development I: Differential emotions theory of early emotional development. In The first draft of this paper was based on an invited address to the Eastern Psychological Association, Apr 1, 1983. John Wiley & Sons.

Jones, Daniel Nelson, and Aurelio Jose Figueredo. 2013. The core of darkness: Uncovering the heart of the dark triad. European Journal of Personality 27 (6): 521–531.

Jordan, Alexander H., and Pino G. Audia. 2012. Self-enhancement and learning from performance feedback. Academy of Management Review 37 (2): 211–231.

Karlsson, Niklas, George Loewenstein, and Duane Seppi. 2009. The ostrich effect: Selective attention to information. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 38 (2): 95–115.

Kasof, Joseph. 1997. Creativity and breadth of attention. Creativity Research Journal 10 (4): 303–315.

Kato, Shoko, and Johan Wiklund. 2011. Doing good to feel good-a theory of entrepreneurial action based in hedonic psychology. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 31 (4): 1.

Kaufman, Jack. 2018. Shedding the light on mental illness and entrepreneurship. Foundr Magazine (Victoria, Australia), May 10. https://foundr.com/mental-illness-and-entrepreneurship/

Keh, Hean Tat, Maw Der Foo, and Boon Chong Lim. 2002. Opportunity evaluation under risky conditions: The cognitive processes of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 27 (2): 125–148.

Kim, Min Young, and Ruth Kanfer. 2009. The joint influence of mood and a cognitively demanding task on risk-taking. Motivation and Emotion 33 (4): 362.

Kirkley, W.W. 2016. Entrepreneurial behaviour: The role of values. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 22 (3): 290–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-02-2015-0042.

Kish-Gephart, Jennifer J., James R. Detert, Linda Klebe Treviño, and Amy C. Edmondson. 2009. Silenced by fear: The nature, sources, and consequences of fear at work. Research in Organizational Behavior 29: 163–193.

Koellinger, Philipp, Maria Minniti, and Christian Schade. 2007. “I think I can, I think I can”: Overconfidence and entrepreneurial behavior. Journal of Economic Psychology 28 (4): 502–527.

Kramer, Matthias, Beate Cesinger, Dominik Schwarzinger, and Petra Gelléri. 2011. Investigating entrepreneurs’ dark personality: How narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy relate to entrepreneurial intention. In Proceedings of the 25th ANZAM conference.

Kreitler, Shulamith. 2004. The dynamics of fear and anxiety. In Psychology of fear, ed. P.L. Gower, 1–17. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Lazarus, Richard S. 1993. From psychological stress to the emotions: A history of changing outlooks. Annual Review of Psychology 44 (1): 1–22.

Lerner, Jennifer S., and Dacher Keltner. 2000. Beyond valence: Toward a model of emotion-specific influences on judgement and choice. Cognition & Emotion 14 (4): 473–493.

———. 2001. Fear, anger, and risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81 (1): 146.

Lerner, Jennifer S., and Larissa Z. Tiedens. 2006. Portrait of the angry decision maker: How appraisal tendencies shape anger’s influence on cognition. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 19 (2): 115–137.

Lerner, Jennifer S., Ye Li, Piercarlo Valdesolo, and Karim S. Kassam. 2015. Emotion and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology 66: 799.

Lindenberg, Siegwart. 2008. Social rationality, semi-modularity and goal-framing: What is it all about? Analyse & Kritik 30 (2): 669–687.

———. 2012. How cues in the environment affect normative behavior. In Environmental psychology: An introduction, ed. L. Steg, A.E. van den Berg, and J.I.M. de Groot. New York: Wiley.

Lindenberg, Siegwart, and Linda Steg. 2007. Normative, gain and hedonic goal frames guiding environmental behavior. Journal of Social Issues 63 (1): 117–137.

Lyubomirsky, Sonja, Laura King, and Ed Diener. 2005. The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin 131 (6): 803.

Mandl, Christoph, Elisabeth S.C. Berger, and Andreas Kuckertz. 2016. Do you plead guilty? Exploring entrepreneurs’ sensemaking-behavior link after business failure. Journal of Business Venturing Insights 5: 9–13.

Maner, Jon K., and Mary A. Gerend. 2007. Motivationally selective risk judgments: Do fear and curiosity boost the boons or the banes? Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 103 (2): 256–267.

Markman, Gideon D., David B. Balkin, and Robert A. Baron. 2002. Inventors and new venture formation: The effects of general self-efficacy and regretful thinking. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 27 (2): 149–165.

Mathieu, Cynthia, and Étienne St-Jean. 2013. Entrepreneurial personality: The role of narcissism. Personality and Individual Differences 55 (5): 527–531.

McMullen, Jeffery S., and Dean A. Shepherd. 2006. Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review 31 (1): 132–152.

Mitchell, J. Robert, and Dean A. Shepherd. 2011. Afraid of opportunity: The effects of fear of failure on entrepreneurial action. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 31 (6): 1.

Mitchell, Ronald K., Brandon Randolph-Seng, and J. Robert Mitchell. 2011. Socially situated cognition: Imagining new opportunities for entrepreneurship research. Academy of Management Review 36 (4): 774–776.

Möbius, Markus M., Muriel Niederle, Paul Niehaus, and Tanya S. Rosenblat. 2011. Managing self-confidence: Theory and experimental evidence. No. w17014. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Morgan, John, and Dana Sisak. 2016. Aspiring to succeed: A model of entrepreneurship and fear of failure. Journal of Business Venturing 31 (1): 1–21.

Ocasio, William. 1997. Towards an attention-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal 18: 187–206.

Öhman, A. 2000. Fear. In Encyclopedia of stress, ed. G. Fink, vol. 2, 111–116. San Diego: Academic Press.

Öhman, Arne. 2008. Fear and Anxiety: Overlaps and Dissociations. In Handbook of Emotions, ed. Michael Lewis, Jeanette M. Haviland-Jones, and Lisa Feldman Barrett, 709–29. New York: Guilford Press.

Pinto, Yair, Andries R. van der Leij, Ilja G. Sligte, Victor A.F. Lamme, and H. Steven Scholte. 2013. Bottom-up and top-down attention are independent. Journal of Vision 13 (3): 16–16.

Plutchik, Robert. 2003. Emotions and life: Perspectives from psychology, biology, and evolution. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Podoynitsyna, Ksenia, Hans Van der Bij, and Michael Song. 2012. The role of mixed emotions in the risk perception of novice and serial entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (1): 115–140.

Rachman, Stanley J. 1990. Fear and courage. New York: WH Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co.

Rauch, Andreas, and Isabella Hatak. 2015. The dark side of entrepreneurship: Applying reinforcement sensitivity theory to explain entrepreneurial behavior (SUMMARY). Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 35 (3): 17.

Reiss, Steven. 1980. Pavlovian conditioning and human fear: An expectancy model. Behavior Therapy 11 (3): 380–396.

Ronningstam, Elsa, and Arielle R. Baskin-Sommers. 2013. Fear and decision-making in narcissistic personality disorder—A link between psychoanalysis and neuroscience. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 15 (2): 191.

Roseman, Ira J., and Craig A. Smith. 2001. Appraisal theory. In Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research, 3–19. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Russell, James A., and Lisa Feldman Barrett. 1999. Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: Dissecting the elephant. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76 (5): 805.

Schulman, Paul R. 1989. The “logic” of organizational irrationality. Administration and Society 21 (1): 31–53.

Schwarz, Norbert. 2002. Situated cognition and the wisdom of feelings: Cognitive tuning. In The wisdom in feelings, ed. L. Feldman Barrett and P. Salovey, 144–166. New York: Guilford Press.

Schwarz, Norbert, and Gerald L. Clore. 2003. Mood as information: 20 years later. Psychological Inquiry 14 (3–4): 296–303.

Sharot, T. 2012. The optimism bias: Why we’re wired to look on the bright side. London: Hachette UK.

Shepherd, Dean A., and Donald F. Kuratko. 2009. The death of an innovative project: How grief recovery enhances learning. Business Horizons 52 (5): 451–458.

Shepherd, Dean A., and Holger Patzelt. 2017. Trailblazing in entrepreneurship: Creating new paths for understanding the field. Cham: Springer.

Shepherd, Dean A., and Marcus T. Wolfe. 2014. Entrepreneurial grief. In Wiley encyclopedia of management. Chichester: Wiley.

Shepherd, D.A., J.S. Mcmullen, and W. Ocasio. 2017. Is that an opportunity? An attention model of top managers’ opportunity beliefs for strategic action. Strategic Management Journal 38 (3): 626–644. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2499.

Singh, Smita, Patricia Doyle Corner, and Kathryn Pavlovich. 2015. Failed, not finished: A narrative approach to understanding venture failure stigmatization. Journal of Business Venturing 30 (1): 150–166.

Sjöström, Tomas, Levent Ülkü, and Radovan Vadovic. 2017. Free to choose: Testing the pure motivation effect of autonomous choice (No. 17-11). Carleton University, Department of Economics.

Stephan, Ute. 2018. Entrepreneurs’ mental health and well-being: A review and research agenda. Academy of Management Perspectives 32 (3): 290–322.

Strobel, Maria, Andranik Tumasjan, and Matthias Spörrle. 2011. Be yourself, believe in yourself, and be happy: Self-efficacy as a mediator between personality factors and subjective well-being. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 52 (1): 43–48.

Tafti, Mahnaz Akhavan, Mansoor Ali Hameedy, and Nahid Mohammadi Baghal. 2009. Dyslexia, a deficit or a difference: Comparing the creativity and memory skills of dyslexic and nondyslexic students in Iran. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 37 (8): 1009–1016.

Tan, Hui Bing, and Joseph P. Forgas. 2010. When happiness makes us selfish, but sadness makes us fair: Affective influences on interpersonal strategies in the dictator game. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 46 (3): 571–576.

Treisman, Anne M., and Garry Gelade. 1980. A feature-integration theory of attention. Cognitive Psychology 12 (1): 97–136.

Trope, Yaacov, and Eva M. Pomerantz. 1998. Resolving conflicts among self-evaluative motives: Positive experiences as a resource for overcoming defensiveness. Motivation and Emotion 22 (1): 53–72.

Tseng, C.C., S.C. Fang, and Y.T.H. Chiu. 2011. Search activities for innovation: An attention-based view. International Journal of Business 16 (1): 51–70.

Ucbasaran, Deniz, Dean A. Shepherd, Andy Lockett, and S. John Lyon. 2013. Life after business failure: The process and consequences of business failure for entrepreneurs. Journal of Management 39 (1): 163–202.

Walsh, Grace S. 2017. Re-entry following firm failure: Nascent technology entrepreneurs’ tactics for avoiding and overcoming stigma. In Technology-based nascent entrepreneurship, 95–117. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Walsh, G.S., and J.A. Cunningham. 2016. Business failure and entrepreneurship: Emergence, evolution and future research. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship 12 (3): 163–285.

———. 2017. Regenerative failure and attribution: Examining the underlying processes affecting entrepreneurial learning. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research 23 (4): 688–707.

Watson, David, and Auke Tellegen. 1985. Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychological Bulletin 98 (2): 219.

Weiss, Howard M., and Russell Cropanzano. 1996. Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In Research in organizational behavior: An annual series of analytical essays and critical reviews, ed. B.M. Staw and L.L. Cummings, vol. 18, 1–74. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science/JAI Press.

Welpe, Isabell M., Matthias Spörrle, Dietmar Grichnik, Theresa Michl, and David B. Audretsch. 2012. Emotions and opportunities: The interplay of opportunity evaluation, fear, joy, and anger as antecedent of entrepreneurial exploitation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (1): 69–96.

Wiklund, Johan, Isabella Hatak, Holger Patzelt, and Dean Shepherd. 2018. Mental disorders in the entrepreneurial context: When being different can be an advantage. Academy of Management Perspectives 32 (2): 182–206.

Wolfe, Marcus T., and Dean A. Shepherd. 2015. What do you have to say about that? Performance events and narratives’ positive and negative emotional content. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 39 (4): 895–925.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix