Abstract

This chapter explores the behaviours and impact of consumer engagement with luxury clothing brands on the WeChat social media platform. It presents an investigation into how young Chinese fashion consumers use WeChat to understand and engage with luxury fashion brands and how they engage with other consumers and interested stakeholders during their shopping experience. Our results suggest that consumers do use WeChat extensively to engage with luxury clothing brands, but in doing so currently place the greatest trust for their fashion and product knowledge in the opinions of those in their WeChat friendship groups and WeChat fashion bloggers rather than directly with the brands themselves.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

This chapter explores the behaviours and impact of millennial Chinese fashion consumers’ engagement with luxury clothing brands on the WeChat social media platform. Our results suggest that consumers use WeChat extensively to engage with luxury brands and with other consumers within their friendship groups and that these interactions may influence purchasing decisions of luxury fashion brands. There is evidence to suggest that the greatest level of consumer trust for fashion and product knowledge resides in the opinions of these WeChat friendship groups and independent fashion bloggers than directly with the brands themselves. This has implications for the tactics brands are currently employing on social media channels.

China is now the second largest economy in the world and since the introduction of economic reforms in 1978 it has experienced dramatic economic growth and managed to successfully weather the 2008 global economic crisis (EIU 2016). Consumers in China now account for approximately 30% of all global luxury consumption, and this is expected to rise to 44% by 2025 (Bu et al. 2017). There are several reasons underlying this anticipated growth. First, there is a drift towards a harmonisation of the prices of Western luxury goods so that they are no longer priced at a premium in China, causing Chinese consumers to purchase luxury goods at home rather than travel to Paris, Milan or Tokyo. Second, tighter custom controls now limit the grey market ‘diagou’ (Chinese nationals based overseas taking orders and sending goods into China). Finally, the purchasing growth of the millennial consumer (those born between 1980 and 2000) is also a factor. These consumers seek engagement with brands online through new social media platforms (Atsmon and Magni 2011).

Chinese millennials are identified as the new breed of “super consumer” and are big spenders for luxury brands (Simmers et al. 2014). There are around 400 million in China. Many are from the only-child generation who have grown up during China’s economic reforms and benefitted considerably through its growing prosperity. They are becoming more individualistic and are using fashion clothing as a way of expressing their individualism. Kuo et al. (2017, p. 1) points out that:

Because they grew up socializing and having fun online, shopping to them is not just shopping. It’s socializing and entertainment all merged together. They are drivingChina’s e-commerce toward a futuristic orientation with mobile commerce, social commerce, and entertainmerce.

Chinese millennial consumers prefer fashion clothing brands with Western origins over those with Asian origins and view these brands as symbols of success, prestige and wealth (O’Cass and Siahtiri 2013). Many prefer to interact with brands online via social media platforms than in physical settings. Word-of-mouth communication using social media is their number one influencing factor on their purchase decisions.

WeChat is a social media platform, operating in China, that provides access to a range of facilities including text messaging, voice messaging, video conferencing, sharing of photographs and videos, location sharing and mobile payments. It was launched in China in 2011 and now has 800–900 million active users making it the most popular app for consumers in China to gain fashion insight. Globally, it is the fifth-most-popular social media platform behind Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp and QQ, although we recognise that some social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram are banned in China (Statista 2018). There are ten million merchants with accounts on WeChat allowing consumers to shop for a wide range of products and services (Economist 2016). The attractions of using WeChat include a very large audience reach, one-to-one messaging functionality, a direct payment system and the facility to exercise a high level of brand control, that is, brands can build their own site, fulfil orders and deal with customers directly on WeChat.

The clothing sector is one of the most popular industry sectors on WeChat. However, luxury fashion brands have been slow in general to use digital channels, for example, Louis Vuitton Moet Hennessy (LVMH) only announced in 2017 that they would be launching a multi-luxury brand digital-commerce site (Williams 2017). This is partly due to a desire to protect the exclusivity of the product and a preference to focus on store presence for brand experience. They have been also less active on social media in particular than many other parts of the retail sector, but they are increasingly changing this position. They recognise that there is a generation of consumer who wish to engage online with the brand directly, and to engage with other consumers about the brand in online brand communities (OBCs). For example, Cartier, Tiffany and Bulgari all use WeChat for some aspects of sales, marketing and customer interactions. Burberry have developed a digital platform to allow consumers to instantly access runway collections from in-store and online channels (Arthur 2016). Chanel, Dior and Gucci have developed their own mobile apps and engage with consumers through a range of social media channels. Despite the huge market opportunities presented by social media in general and WeChat in particular to enable luxury fashion consumers to connect and interact with luxury brands, little is known about the detail of this engagement. Many studies focusing on consumer engagement with luxury brands have, in the main, focused on those popular within Western economies such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram (e.g. Jin and Seung 2012; Dhaoui 2014).

The purpose of this chapter is to present empirical research exploring how millennial Chinese luxury fashion brand consumers engage with luxury fashion brands and other consumers through OBCs on WeChat. We have three objectives:

-

1.

to discover their underlying motivations for using WeChat to access luxury brands;

-

2.

to understand their perceptions of brands’ direct online engagement with them; and

-

3.

to explore how millennial consumers engage with other customers to discuss luxury fashion brands through WeChat.

This research provides two points of differentiation from previous work. First, we will explore the role of identity boundaries. Social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter allow OBCs to form easily and they are open to anyone. Yet, whilst members can join with ease, they can choose to reveal little of their identity, remain anonymous and maintain their privacy. On the other hand, whilst WeChat members are well known to each other, friends are admitted from the contact list on the cell phone to WeChat (Lien et al. 2017); it does provide a private space facility enabling people to communicate only with selected others allowing “Circles of Friends” to form (Zhang et al. 2016). It is not well understood quite what impact these WeChat friendship circles have upon consumer engagement. Second, whilst research is emerging on various aspects of consumer behaviour patterns on WeChat (e.g. Lien et al. 2017; Gan 2017), this work tends to focus on general consumers rather than millennial Chinese luxury fashion brand consumers. This research will add to the emerging literature on OBCs, a growing Western interest in WeChat and the use of social media within China.

Consumer Motivation for Social Media Engagement

Social mediaplatforms like WeChat are seen as a driving force for consumer engagement due to their participatory nature and focus on relationships. The Users and Gratification Theory (U>) (Katz et al. 1974) is a theoretical framework that argues that people’s social and psychological needs influence the media they choose, how they use that media and what gratifications it gives them. These needs can be placed into five categories:

-

cognitive needs, including acquiring information, knowledge and understanding;

-

affective needs, including emotion, pleasure and feelings;

-

personal integrative needs, including credibility, stability and status;

-

social integrative needs, including interacting with family and friends; and

-

tension release needs, including escape and diversion.

Another type of categorisation is that there are utilitarian and hedonic reasons for usage. Hedonic gratification includes enjoyment, entertainment, fantasy, escapism and self-expression. An addition to this is the feeling of empowerment such as influence over other consumers or the brand and remuneration, for example, receiving some kind of economic reward such as free samples or discounts (Wang and Fesenmaier 2003). Utilitarian gratification includes achievement, mobility, immediacy and information seeking from other consumers and brands.

There are a range of other gratification models. Dunne et al. (2010) identified seven gratifications sought from social media which include communication, friending, identity creation and management, entertainment, escapism, alleviation of boredom, information search and social interaction. Muntinga et al. (2011) identified six gratifications: information, personal identity, integration and social integration, entertainment, empowerment and remunerations. Dolan et al. (2016) identified four main drivers of consumer engagement as utilitarian, entertainment, remuneration and socialisation. Obtaining social gratifications has emerged as key to motivating consumers to engage with social media platforms, to develop friendships, to find relevant information and to have fun (Ruiz-Mafe et al. 2014). Drawing on studies based upon U>, we focus upon hedonic, utilitarian and social gratifications on WeChat.

Online Brand Communities: Definitions and Characteristics

A brand community is defined as a “specialised, non-geographically bound community, based on a structured set of social relations amongst admirers of the brand” (Muniz and O’Guinn 2001). The OBCs may be regarded as specialised brand communities that take place in a virtual setting where members interact with each other, exchange information or express their passion for the brand, and their interaction is often mediated. The OBC’s core factor is the brand itself but ultimately it exists and persists due to the relationship forged between members. The social identity of the brand community is implied by three key commonalities that are always present: (1) consciousness of kind, (2) shared rituals and traditions and (3) moral responsibility.

Consciousness of kind is the most important marker. It describes the fact that members feel a solid connection to the brand but more significantly that they feel a stronger connection to one another. For a luxury brand, this suggests that members connected to the community place a high value on the brand, have knowledge to share about the brand and appreciate that other members value the brand in a similar way. Shared rituals and traditions is a process through which brand community members maintain, reinforce and diffuse the culture, values, norms, behaviours, specific language signs and symbols, history and consciousness of the community itself. For a luxury brand, this suggests members place a high value on opportunities for a shared discussion on the history of the brand, the founder, the background to certain popular products and a change in logos. Finally, moral responsibility manifests itself through the community members’ attitude to retain old members and integrate new ones and to support them to enjoy a meaningful brand consumption experience. For a luxury brand this suggests members place a high value being able to support other members in the community.

Whilst there is considerable work on the effect of OBCs within a social media context (e.g. Laroche et al. 2012; Brodie et al. 2013; Brogi et al. 2013), it is largely based on OBCs created by fans enthusiastic of a specific brand. The role of the brand is passive, and the brand owner may not have knowledge regarding the existence of the community. On the other hand, an official OBC is one created and sponsored by the luxury brand itself with the aim to proactively enable members to exchange fashion opinions and receive brand information with the aim of building a collaborative community that serves both the consumers and the brand itself (Okonkwo 2009). For example, within the Facebook online brand community, consumer engagement can occur at three levels (Schultz 2016). The first level is a consumer becoming a ‘fan’ of the brand page by clicking ‘like’ on a brand page. The second level is a brand posting onto a Facebook page, for example, video which may encourage a post from a consumer. The third level is the consumer liking, commenting and sharing information within which thus extends the reach of the information.

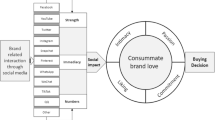

Figure 12.1 shows the flows of social interactions within a consumer-brand-consumer triad on Facebook. Consumers can interact with other consumers and the luxury fashion brand. Luxury brands can initiate social interactions with consumers by posting content on a Facebook page. The bold arrows represent the public nature of the interactions shared within the community. There is a single external community circle represented as a dotted line showing that interactions can also extend beyond the community when sharing content with friends of fans (Lipsman et al. 2012). Key characteristics of an OBC on Facebook are (1) members are individual consumers, (2) members are anonymous and (3) social interactions are public and shared within and beyond the community.

Figure 12.2 shows the flows of social interactions within a consumer-brand-consumer triad on WeChat. The key difference in this model is that the community circle is represented as a solid line and shows interactions remaining largely within the ‘circle of friends’ community. Within this model, the inner solid line represents social interactions are contained within the ‘circle of friends’ group with the outer dotted line representing the opportunity to share social interactions when sharing with friends of fans. The key characteristics of an OBC on WeChat are as follows: (1) membership is within the ‘circle of friends’ groups, (2) members are known to each other and (3) social interactions take place within the Circle of Friends’ Groups but can be shared beyond this community.

Consumers Direct Online Engagement with Brands

From a luxury brand’s perspective, an important benefit of an OBC is the opportunity it presents for direct engagement with consumers. Brand-consumer engagement has several elements: creating and posting relevant and meaningful content, relinquishing some degree of control over content and allowing sharing of content amongst OBC friends. Collectively, this can encourage a sense of community among members and facilitate conversation and dialogue.

Kozinets (2014) proposed four strategies which could be adopted by brands to maximise the opportunities presented within OBCs. Brands can use OBCs to research and understand their customers by monitoring opinions, information and suggestions, to invite their community to innovate and co-create the brand offering, to demonstrate commitment to consumers by responding to service needs and finally to communicate promotions within the community. On WeChat there are two types of relationships brands that have the potential to develop with consumers: business relationships and friendships (Yang et al. 2016). Business relationships can be developed by posting product-related information or positive customer feedback on their newsfeeds. Friendships can be developed by commenting on customer updates and interacting with customer content.

In developing strategies for engagement within OBCs, however, brands must note that the consumer experience is affected by the way in which the brand administers the OBC (Payne et al. 2009). For example, the brand could affect how members establish relationships with each other and the topics, conversations and actions within the community. The inclusion of commercial actions therefore may be negatively perceived by consumers (Clemons 2009). Trust between consumers and the brand and between consumers and consumers is a pivotal driver in an OBC as a community cannot be seen to be successful if its members are unable to rely upon it (Belanger et al. 2002). Consumers expect a brand company to act as another member, providing information and sharing control but without taking commercial advantage of its position within the community (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2010).

Consumer-to-Consumer Engagement

Considerable attention has been paid to the term consumer engagement. For example, Dessart et al. (2015) recognised consumer engagement as a multi-dimensional concept broadly identifying three key engagement dimensions of commitment to a brand, cognitive, affective and behavioural commitment. Much of this work has been developed with a view to giving managerial advice on the consumer-brand and brand-consumer engagement. Less attention is paid to developing an understanding of the scope and scale of managerial attention that needs to be paid to fostering commitments to the brand by enabling consumers to engage with each other.

There remains some debate as to what constitutes the scope of consumer-to-consumer (C2C) engagement. Broadly, it describes behaviours that motivates consumers to engage with each other about one or more brands. Example behaviours include word-of-mouth recommendations, helping others, blogging and writing reviews (Van Doorn et al. 2010). A desire for social engagement to satisfy hedonic needs is one driving force for C2C engagement, and a desire to take on additional pre-purchasing information from different sources to mitigate the risk of a poor purchase to satisfy utilitarian needs is another. Adjei and Noble (2012) showed that positive information shared by community members has a stronger moderating influence on purchasing behaviour than negative information, and that OBCs are effective customer retention tools for retaining both experienced and novice customers.

Brand-led online recommender systems that collate and present summaries of anonymised views of products already purchased offer one form of C2C engagement. Less data-driven informal OBCs offer another. However, there remains much more to learn about the impact that different types of community have on consumers’ understanding, commitment and purchasing decisions towards a brand. Communities have different properties, for example, size, range of expertise, geographical reach, anonymity and online activity levels. They can range from large, anonymous, geographically dispersed set of generalists to a small, well-known, local specialists. Product context, for example, perceived value, price, availability also plays its part on how such C2C engagement is to be constructed. Some luxury brands, for example, offer discrete invitations to product launch events to selected consumers only.

Methodology

To address the research objectives, a number of open-ended questions were asked of a modest sample of Chinese millennial luxury fashion consumers. We adopted a phenomenological approach as it provides a firm basis for examining underlying consumer behaviour and motivations consistent with previous research in consumer engagement and social interactions within OBCs. Twelve postgraduate native Chinese millennial students studying fashion marketing at a UK university were invited to participate in this research. They all had detailed knowledge of luxury fashion brands—most had made purchases of luxury brands in the previous 12 months, and most of them had connected with luxury brands on WeChat. They were also users of Weibo and Baidu and, since they had come to the UK, had become users of Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. To address the research objectives, a number of open-ended questions were asked which centred on three broad areas: social media use and motivation to use WeChat, consumer engagement with luxury brands and consumer engagement within friendships groups.

Empirical Results and Discussion

Chinese Millennials’ Motivations for Using WeChat

The respondents confirmed that they checked their social media accounts very frequently, consistently with reports suggesting that on average, millennials in the UK spend more than eight hours a day connected with digital media and communications (www.digitaldayresearch.co.uk). Chinese millennials have acquired almost 10 years’ experience of using mobile phones and at least 5 years of experience on WeChat. Four main gratifications were identified:

-

to remain connected with family and friends;

-

ease of mobile payments;

-

easy access to products and services;

-

easy access to playing games and watching videos.

The respondents use WeChat to keep in touch with family and friends, gain information and have fun through liking, sharing and commenting on posts within the friendship groups.

keeping in touch with family and friends in friendships groups feels special as you know everyone……you can find out lots of information so if I need to find out information I just go on to my friendships groups.

Another attraction was the facility to create new friendships through the recommendations of a friend via the exchange of electronic business cards, QR codes or the geolocation function which allows you to ‘shake the phone’ to locate new friendships. The respondents also acknowledged they had a wide number of different friendship groups.

Cashless mobile payments and the transfer of money to family and friends are viewed as key advantages of using WeChat. Payment services refer to transactional payments for goods and services and payments as gifts. Sending ‘red letter packets’ and transfer of monies to and from China is highly valued by millennials. The cashless payment facility is underpinned by the complete trust in the parent company, Tencent, to maintain privacy and security of data. The significance of the role of cashless payments has not been highlighted in previous research on social media platforms. Some major Western social media platforms have yet to seamlessly integrate a payment facility.

For Chinese millennials, utilitarian gratifications are satisfied through access to a wide range of products and services on the go regarded as ‘good convenience’ and ‘helps to make life easier’, and by providing the opportunity to access information sources and free calls with communication undertaken via text, pictures, videos, voice messages and use of QR codes. Hedonic gratifications can be satisfied in WeChat because it provides the opportunity to be entertained through access to a wide assortment of games. Doing so creates an enjoyable experience and a focal point for discussion with friendship groups.

Chinese Millennials’ Direct Online Engagement with Brands

Within the sample the decision to engage directly with luxury fashion brands on WeChat varied according to their awareness of the luxury brand’s presence on We Chat, from a sarcastic and incredulous ‘why should I look at luxury brands on WeChat?” to ‘Yes I have connected to luxury fashion brands and follow them on WeChat’. Clearly, even those luxury brands that have a presence on WeChat can do more to promote that presence or to highlight there is the opportunity to connect with the brand.

In WeChat when a member of a friendship group decides to follow a luxury fashion brand, all friends received notifications from the brand on updates and new campaigns. These push notifications are directed from the brand to the consumer and demonstrate evidence of the development of business relations with consumers. However, these are regarded as monologues which may encourage some social interactions within the friendship group but do not satisfy utilitarian gratifications related to brand information (Tsao et al. 2011).

Fashion brands can be followed on WeChat, and one can access the website of fashion brand from WeChat, for example, Valentino, Dior. The luxury fashion brand Burberry was followed by several respondents. Relevant product information was viewed with Wu Yi Tan (Chinese actress) noted in a positive manner as a model on the Burberry WeChat account. The opportunity to view fashion shows, updates on campaigns, and looking for limited edition, exclusive products only available to Chinese consumers was highly valued. This would indicate that followers are actively seeking hedonic gratifications associated with luxury fashion brands, but this is not provided on the WeChat brand community.

A number of respondents noted the use of WeChat Moments posts by brands. WeChat Moments allow luxury brands to create mini programmes, place advertising and create games to encourage engagement and provide hedonic value. The Moments Ads allow brands to place ads in feeds otherwise reserved for posts by friends. It is considered to be a useful strategy to build brand awareness, enhancing interaction with WeChat followers, and provides an opportunity to purchase through these ads. At the time of data collection, there was an awareness of Moments Ads existence but respondents were unsure of their purpose.

Luxury brand posts provide opportunities for C2C social interactions within the friendship group. However, all interactions remain within the confines of the friendship group; thus, any C2C brand and brand to consumer interactions remain within friendship group members. Whilst the opportunity exists to share such information with ‘friends of friends’, the respondents emphatically preferred not to share any brand interaction beyond the friendship group. On Facebook and some other social media platforms, the size of a brand community can be very large as anyone expressing an interest in the brand can become a fan and access social interactions taking place within the community. The size of the brand communities in WeChat, however, is often much more smaller and confined to friendship groups, making it more complex for brands to balance customised messages with economies of scale.

One impact of this is the Chinese millennial luxury brand fashion consumer’s attitude to typical brand company responses. The first type of response is to a consumer post about one of its brands simply takes the terse form of pointing to more specific information on a website or at a nearby geographic store location. The second type of response simply informs consumers that they will receive a more detailed response within 24 hours. Both types of responses are not looked upon favourably even if they may be appropriate. In the first case the response is too short and not personalised. In the second case the timeframe is considered too long to wait (‘… so I searched elsewhere and found the information quickly’). Such responses drive Chinese millennial consumers to seek utilitarian and hedonic gratifications on other channels, for example, Weibo, fashion bloggers, Baidu and Ali Baba.

Due to the nature of friendship groups, there is a preference to maintain the level of social interactions within the friendship group as this is the location of trust within a WeChat community; hence, social gratifications are satisfied by membership within a friendship group. More emphasis is, therefore, placed on the luxury fashion brand to provide utilitarian and hedonic gratifications which may influence purchase decisions taking place within the WeChat community.

The perception of the respondents was that, although luxury fashion brands do often provide relevant information, they are not sufficiently proactively developing relationships through brand communities or allowing consumers to participate with the brand. They are increasingly developing digital business relationships with consumers but not supplementing them with the social relationships which these millennials value in contributing to their purchasing decisions.

Chinese Millennials Engagement with Each Other About Luxury Fashion Brands on WeChat

The respondents confirmed that the social interactions that they experience in small-size friendship groups were a very important contributory factor in the development of their understanding of a brand, its products and for influencing their purchasing decisions. However, they also acknowledged that they also seek the opinions of other ‘experts’ to supplement the advice they get from their friends. Such experts might be personal shoppers, fashion bloggers, journalists or other social media platforms users.

The subject of fashion is a popular topic of conversation within the friendship groups with clothing brands, styles, fashion and inspiration frequently discussed. Methods for exchanging opinions were by ‘liking’, ‘sharing’ and commenting on posts from the brand company and other consumers. These brands are highly sought after despite consumer awareness that the purchase price of these brands is normally higher within China indicating that price harmonisation has not yet fully made an impact.

Common pre-purchase discussion themes include company and brand information and perception, product availability, product locations, purchasing options, style type and colour. Purchasing options include in store, on the website or the possibility of the purchase being made outside China, resurfacing the role of the ‘daigou’. Post-purchase discussion themes include the impact of the purchase, the occasion on which the purchase was used, how it made a person feel, product quality, for example, materials, stitching, location of logo, colour, handle length and width.

The Role of Personal Shoppers

In order to make purchases, friends may set up their own online store in WeChat taking on the role of the personal shopper (daigou) and providing an alternative purchase channel for their friends or relatives regardless of whether the purchase is to be made from stores, websites or online shopping malls. Such a purchase option is valued because it is transacted by a known friend who has the trust of the friendship group. The role of the ‘daigou’ is new within research and has a significant role to play.

Personal shoppers often copy pictures from official websites of luxury brands and provide detailed product information to establish the authenticity of the luxury products. They identify the products that can be accessed outside China. Any friend can contact a personal shopper in private, that is, away from others within the friendship group to make arrangements for the exchange. It maintains the element of privacy as it is not a stranger who is trying to sell something but a reliable known friend.

The Role Key Opinion Leaders

Credible sources of information include following fashion bloggers who are regarded as key opinions leaders with pages on Weibo. Well-known fashion bloggers are seen as fashion ‘it’ girls who provide up-to-the-minute fashion and styling tips on their pages. Often, these bloggers may sell their own brand of clothing. The value of both the luxury fashion brand and the blogger is enhanced when the luxury fashion brand is namechecked within posts, pictures and videos of the fashion blogger. These pictures are often styled as fashion shoots similar to those of fashion magazines such as Vogue and attract the attention of members within a friendship group who desire detailed information on the luxury brand. The use of Chinese celebrities enhances the attraction of luxury fashion brands and creates an opportunity for social interactions with the friendship group.

Other Social Media Platforms

Other popular digital channels used by the Chinese millennials include Weibo, Baidu and Ali Baba. Weibo in particular is considered to be a fast and easy-to-use source of information. However, as it is considered to have significant Chinese government oversight, the comments left on these pages are not considered to be trustworthy. Official websites of luxury fashion brands provide useful information.

Discussion of Results

Chinese millennials utilise social media in a similar manner to many Western millennials and use WeChat extensively to engage with luxury fashion brands. They are driven by social, utilitarian (including payment services) and hedonic gratifications to use WeChat. Social interactions within OBCs on WeChat occur within friendships groups placing greater emphasis on the luxury fashion brand to leverage these groups to satisfy millennial purchasers’ utilitarian and hedonic gratifications and hence influence purchasing decisions. Whilst luxury fashion brands are increasing their social media presence, they are often transaction-focused and offer limited opportunities for consumer-brand-consumer interactions. This encourages OBCs to form as independent fan-based communities in the absence of official brand-led OBC over which the brand has more influence. It also encourages the seeking of detailed brand-related information and content from a wider range of sources beyond friendship groups.

These trends point to an amended model of flows of social interactions within a consumer-brand-consumer triad for WeChat (Fig. 12.3). First, the flows of social consumer-to-consumer (C2C) interactions are strong with trust within the friendship groups represented by a bold line. The flows of social interactions between consumer-brand-consumer are weak which is reflected by the lack of an engagement strategy by luxury fashion brands on WeChat represented by the single line. The flows of interactions remain within the friendship groups with the potential to share information with friends of fans beyond the community, yet are not encouraged by friendship group members. The model includes an arrow within the C2C reaching beyond the friendship group as friends seek hedonic and utilitarian gratifications beyond the OBC. The key characteristics are (1) membership is within ‘Circle of Friends’ Groups, (2) members are known to each other, (3) preference for social interactions are shared only within Circle of Friends’ group and (4) members seek luxury fashion brand-related information and content beyond the OBC.

Luxury fashion brands, therefore, need to consider how best to create relationships within friendship groups and develop strategies that will influence purchase decisions. This would allow the luxury fashion brands to satisfy hedonic and utilitarian gratifications within WeChat and therefore diminish the need for consumers to search elsewhere for such needs. For example, knowing the leverage that friends have on each other should encourage brands to win over at least one ‘champion’ who will then leverage their influence over their circles of friends. This might mean providing highly specific, relevant and timely brand information to fewer but very well-connected consumers and encouraging them to share this with their friends within their friendship circles to extend the reach of the brand.

Conclusions

Luxury fashion brands need to make millennial consumers aware of their presence on WeChat and consider their engagement strategy on this platform. The primary motivators for using WeChat for millennials are socialisation, payment facilities, utilitarian and hedonic gratifications. Chinese millennials value comments within their friendship groups and place great trust in this community preferring social interactions to remain within the friendship group. Social gratifications are satisfied by membership within a friendship group. This places greater emphasis on luxury fashion brands with OBCs on WeChat to satisfy hedonic and utilitarian gratifications. At present most luxury brands lack sophisticated engagement strategies on WeChat. This is encouraging the development of the ‘daigou’ within friendship groups and a need to satisfy hedonic and utilitarian gratification beyond the OBC. Luxury fashion brands should consider how best they can make use of each consumer-brand-consumer interaction. They should be more strategic with their use of WeChat communities by offering consumers the opportunity for increased engagement, for example, presenting the latest brand information on exclusive products with links to videos of latest campaigns on these products. They should also consider connecting with key influencers with friendship groups and the use of influential bloggers in an integrated manner.

References

Adjei, M., & Noble, C. (2012). The influence of C2C communications in online brand communities on customer purchase behaviour. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38(5), 634–653.

Arthur, R. (2016, February 5). Digital pioneer Burberry does it again, this time radicalizing its whole fashion calendar. Forbes.

Atsmon, Y., & Magni, M. (2011). China’s new pragmatic consumers. The McKinsey Quarterly, 1.

Belanger, F., Hiller, J., & Smith, W. (2002). Trustworthiness in electronic commerce: The role of privacy, security, and site attributes. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 11(2002), 245–270.

Brodie, R. J., Ilic, A., Juric, B., & Hollebeek, L. (2013). Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 105–114.

Brogi, S., Calabrese, A., Campisi, D., Capece, G., Costa, R., & Di Pillo, F. (2013). The effects of online brand communities on brand equity in the luxury fashion industry. International Journal of Engineering Business Management Special Issue on Innovation in Fashion Industry, 5(32), 1–9.

Bu, L., Servoingt, B., Kim, A., & Yamakawa, N. (2017). Chinese luxury consumers: The 1 trillion renminbi opportunity. From www.mckinseychine.com. Accessed 24 Aug 2017.

Clemons, E. K. (2009). The complex problem of monetizing virtual electronic social networks. Decision Support Systems, 48(1), 46–56.

Dessart, L., Veloutsou, C., & Morgan-Thomas, A. (2015). Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A social media perspective. Journal of Product Management, 24(1), 28–42.

Dhaoui, C. (2014). An empirical study of luxury brand marketing effectiveness and its impact on consumer engagement on Facebook. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 5(3), 209–222.

Dolan, R., Conduit, J., Fahy, J., & Goodman, S. (2016). Social media engagement behaviour: A uses and gratifications perspective. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 24(3–4), 261–277.

Dunne, A., Lawlor, M.-A., & Rowley, J. (2010). Young people’s use of online social networking sites – A uses and gratifications perspective. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 4(1), 46–58.

Economist. (2016). WeChat’s world. https://www.economist.com/business/2016/08/06/wechats-world. Accessed 30 June 2018.

EIU. (2016). The Chinese consumer in 2030. The Economist Intelligence Unit.

Gan, C. (2017). Understanding WeChat users’ liking behavior: An empirical study in China. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 30–39.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Malthouse, E., Friege, C., & Skiera, B. (2010). The impact of new media on customer relationships: From bowling to pinball. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 311–330.

Jin, A., & Seung, A. (2012). The potential of social media for luxury brand management. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 30(7), 687–699.

Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1974). Uses and gratifications research. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 37(4) (1973–1974), 509–523.

Kozinets, R. (2014). Social brand engagement: A new idea. GfK Marketing Intelligence Review, 6(2), 8–15.

Kuo, Y., Feng, H., & Ren, J. (2017). Oppositional brand loyalty in online brand communities perspectives on social identity theory and consumer-brand relationship. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research: JECR, 18(3), 254–268.

Laroche, M., Habibi, M., Marie-Odile, R., & Sankaranarayanan, R. (2012). The effects of social media based brand communities on brand community markers, value creation practices, brand trust and brand loyalty. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1755–1767.

Lien, C.-H., Cao, Y., & Zhou, X. (2017). Service quality, satisfaction, stickiness, and usage intentions: An exploratory evaluation in the context of WeChat services. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 403–410.

Lipsman, A., Mud, G. R., Rich, M., & Bruich, S. (2012). The power of “like”: How brands reach (and influence) fans through social media marketing. Journal of Advertising Research, 52(1), 40–52.

Muniz, A., & O’Guinn, T. (2001). Brand community. Journal of Consumer Research, 27(4), 412–432.

Muntinga, D., Moorman, M., & Smit, E. (2011). Introducing COBRAs: Exploring motivations for brand-related social media use. International Journal of Advertising, 30(1), 13.

O’Cass, A., & Siahtiri, V. (2013). In search of status through brands from Western and Asian origins: Examining the changing face of fashion clothing consumption in Chinese young adults. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 20(6), 505.

Okonkwo, U. (2009). Sustaining the luxury brand on the internet. Journal of Brand Management, 16(5–6), 302.

Payne, A., Storbacka, K., Frow, P., & Knox, S. (2009). Co-creating brands: Diagnosing and designing the relationship experience. Journal of Business Research, 62(3), 379–389.

Ruiz-Mafe, C., Marti-Parrero, J., & Sanz-Blas, S. (2014). Key drivers of consumer loyalty to Facebook fan pages. Online Information Review, 38(3), 362–380.

Schultz, C. (2016). Insights from consumer interactions on a social networking site: Findings from six apparel retail brands. Electronic Markets, 26(3), 203–217.

Simmers, C. S., Parker, R. S., & Schaefer, A. D. (2014). The importance of fashion: The Chinese and U.S. gen Y perspective. Journal of Global Marketing, 27(2), 94–105.

Statistica. (2018). https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/. Accessed 5 April.

Tsao, H.-Y., Berthon, P., Pitt, L. F., & Parent, M. (2011). Brand signal quality of products in an asymmetric online information environment: An experimental study. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 10(4), 169–178.

Van Doorn, J., Lemon, K. N., Vikas Mittal, V., Nass, S., Pick, D., Pirner, P., & Verhoef, P. C. (2010). Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 253–266.

Wang, Y., & FesenMaier, D. R. (2003). Assessing motivation of contribution in online communities: An empirical investigation of an online travel community. Electronic Markets, 13(1), 33–45.

Williams, R. (2017). LVMH raises luxury e-commerce stakes with multi-brand site. Bloomberg Wire Service.

Yang, S., Chen, S., & Li, B. (2016). The role of business and friendships on WeChat business: An emerging business model in China. Journal of Global Marketing, 29(4), 174–187.

Zhang, H., Wang, Q., & Ma, X. (2016). Research on WeChat marketing path of enhancing customer marketing experiences. Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), 4487–4490.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Siddiqui, N., Mannion, M., Marciniak, R. (2019). An Exploratory Investigation into the Consumer Use of WeChat to Engage with Luxury Fashion Brands. In: Boardman, R., Blazquez, M., Henninger, C.E., Ryding, D. (eds) Social Commerce. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03617-1_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03617-1_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-03616-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-03617-1

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)