Abstract

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) is an empirically supported, manualized intervention for addressing disruptive behaviors in young children (Eyberg. Child and Family Behavior Therapy 10:33–46, 1988; Neary and Eyberg. Infants and Young Children 14:53–67, 2002). Recently, researchers have expanded the use of PCIT with diverse populations to include children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD; Hansen & Shillingsburg. Child and Family Behavior Therapy 38:318–330, 2016). Adaptations to the original PCIT protocol may be needed to address core characteristics of ASD that otherwise may limit treatment effectiveness with this population. Characteristics of ASD that should be considered include deficits in social communication and interactions, high levels of rigidity and stereotypic behavior, and circumscribed interests and preferences. This chapter will discuss how the characteristics of ASD may pose challenges to the standard PCIT approach and provide detailed recommendations for several adaptations including altering the mastery criteria and adding preference assessments, stimulus-stimulus pairing, mand training, instructional fading, errorless prompting, and three-step prompting. To provide guidance and suggestions to PCIT clinicians, the authors’ experiences working with parents of children with ASD in PCIT are discussed in addition to a case study (Hansen and Shillingsburg. Child and Family Behavior Therapy 38:318–330, 2016).

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Overview of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) is an empirically supported intervention for young children experiencing behavioral or emotional challenges (Eyberg, 1988; Neary & Eyberg, 2002). The goal of PCIT is to change negative parent-child interactions into warm, affectionate interactions using components of several therapeutic approaches (Eyberg, 1988). PCIT is divided into two phases: Child-Directed Interaction (CDI) and Parent-Directed Interaction (PDI ; McNeil & Hembree-Kigin, 2011). During the CDI phase , parents are trained to provide their child with near continuous attention in the form of labeled praises, reflections of vocalizations, and descriptions of their child’s desirable behaviors. Once mastery criteria for CDI are met, families move on to the PDI phase of treatment . PDI focuses on reducing child noncompliance through utilizing effective commands and a structured discipline procedure.

1.1 Strategies for Reducing Problem Behavior in CDI

Many families are referred to PCIT due to the high incidence of problematic child behavior such as negative attention seeking. Often, parents may be unaware that their responses to a child’s negative behaviors can worsen the incidence and severity of the behavior in question. Therefore, PCIT teaches caregivers to use positive attention for child desirable behaviors , limit periods of attention deprivation, and reduce the likelihood that children will engage in problem behavior maintained by attention (Shillingsburg, 2004). In CDI , parental attention is removed following a child’s problem behavior therefore placing the attention-seeking behavior on extinction. The combination of increased attention during play and withheld attention during problematic behavior is a powerful strategy in improving parent-child interactions.

Not all problematic behavior is evoked by attention deprivation however. During CDI , parents are also taught to refrain from presenting demands and questions to their child. When parents place rapid-fire, developmentally inappropriate, challenging, or vague demands upon a child, it is more likely the child will fail at the request or misbehave, thus preventing a positive parent-child interaction from occurring. The child’s inability or disinterest to comply with a demand (to escape a nonpreferred activity) can significantly hinder the development of a positive parent-child relationship. Likely, in these cases, the child has previously been successful in avoiding or delaying a parent’s demand . In some cases, the problematic behavior may also lead to parents asking less and less of their children, further reinforcing the child’s likelihood to engage in that problematic behavior. In extreme cases, the parent’s mere presence may become a signal to the child that demands are coming and that playtime is about to be over. By eliminating demands and questions and replacing them with preferred activities and parent engagement that the child enjoys, parental interaction becomes increasingly associated with positive reinforcement. The child comes to value interactions with the parent over time, therefore creating motivation to access parental interaction through desirable behaviors (Shillingsburg, 2004). Improving the child’s response to demands is subsequently addressed in the PDI phase.

1.2 Strategies for Reducing Problem Behavior in PDI

In the PDI phase of PCIT, parents are taught to simplify the commands they issue to their children while still utilizing CDI skills . Further, parents are taught to provide consistent consequences for child compliance (i.e., positive reinforcement) and for problem behavior (e.g., planned ignoring, structured discipline strategy). By reducing the complexity of demands, parents increase the likelihood of child compliance , which creates more opportunities to provide reinforcement for their child’s behavior. Providing positive reinforcement for compliance and appropriate behaviors increases the likelihood of future child compliance and instances of desirable behavior. Over time, the initiation of a demand comes to signal the availability of reinforcement, which promotes appropriate behaviors rather than evoking problematic behaviors (Shillingsburg, 2004).

1.3 Behavior Analytic Interpretation of PCIT

We suspect that the success of PCIT is due to the intervention’s focus on addressing underlying motivation-behavior-reinforcement relations (Shillingsburg, 2004). If problem behavior is evoked because the child wants to avoid interacting with his/her parent, PCIT makes interaction with the parent valuable through pairing it with reinforcement. In addition, PCIT teaches parents to provide higher frequency and higher quality attention when the child is not engaging in problem behaviors; it also teaches parents to minimize attention when problem behavior does occur. Understanding the behavior change mechanisms responsible for the success of PCIT is particularly critical when considering the expansion of PCIT to different populations (e.g., families of children with autism spectrum disorder [ASD]).

2 Considerations for Children with ASD in PCIT

PCIT is an effective intervention for young children with disruptive behavior disorders and has preliminary support with children with ASD (e.g., Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016; Lesack, Bearss, Celano, & Sharp, 2014; Solomon, Ono, Timmer, & Goodlin-Jones, 2008). However, as clinicians consider utilizing PCIT with families of children with ASD, there are some important factors related to the children’s diagnoses they should consider.

2.1 Foundations of Autism Spectrum Disorder

It is widely known that ASD is associated with less frequent initiation of social interactions , less social interaction in general, and atypical turn-taking patterns (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Anderson et al., 2007; Dawson, Meltzoff, Osterling, Rinaldi, & Brown, 1998; Paul, Orlovski, Marcinko, & Volkmar, 2009; Sheinkopf, Mundy, Oller, & Steffens, 2000; Warren et al., 2010; Zwaigenbaum et al., 2005). These children are also at an increased risk of producing fewer speech-related vocalizations (Patten et al., 2014; Paul, Fuers, Ramsay, Chawarska, & Klin, 2011; Warren et al., 2010), which in turn limits opportunities for caregivers to provide contingent responses. For example, when a baby says, “Ba,” a parent might respond, “Yes! That’s a sheep,” and point to a sheep picture in a storybook. In the absence of that initial vocalization, the parent would not have an explicit occasion to respond and model additional speech.

Warlaumont, Richards, Gilkerson, and Oller (2014) analyzed the microstructure of child-adult interactions for children with and without a diagnosis of ASD. Outcomes indicated that adult responses occur more when a child emits a speech-related vocalization ; in turn, a child is more likely to emit a speech-related vocalization if a previous speech-related vocalization resulted in an immediate response from an adult. In other words, caregivers are more likely to talk to children who have attempted to speak, and children are more likely to continue to speak when their vocalizations are repeated by caregivers. A reduction in vocalization rate leads to fewer iterations of the social feedback loop, reducing the number of child opportunities to learn from contingent social feedback (see also Leezenbaum, Campbell, Butler, & Iverson, 2014; Tamis-LeMonda, Bornstein, & Baumwell, 2001; Yoder & Warren, 1999). This can inadvertently result in a cascading negative effect on language development in the child.

Importantly, studies have also found that greater vocal coordination between infants and adults predicts later language, cognitive, and perceptual ability (Greenwood, Thiemann-Bourque, Walker, Buzhardt, & Gilkerson, 2010; Jaffe, Beebe, Feldstein, Crown, & Jasnow, 2001). This holds true for those individuals with language emerging later in development. For children with developmental disabilities , a mother’s responsiveness to her child’s communicative behaviors has also been shown to predict later language performance (Girolametto, 1988; Yoder & Warren, 1999). These findings suggest that teaching parents to persist in initiating and responding to their child’s attempts at interaction is warranted.

2.1.1 Expressive Language

ASD is characterized by deficits in social communication and social interactions (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). A PCIT clinician may work with a child who has limited expressive language characterized by very few, if any, vocalizations (e.g., words, sounds). Little functional expressive language can make it difficult for parents to understand what a child is communicating, and can make both the child and the parent frustrated. Additionally, opportunities for caregivers to reflect back child vocalizations can be significantly reduced and may prevent standard PCIT CDI mastery criteria from being reached.

2.1.2 Receptive Language

A child’s difficulty with receptive language may also create unique challenges when implementing PCIT for children with ASD. Children with ASD may not comply with demands presented by caregivers because they do not understand the instructions. If this distinction is not recognized, inappropriate procedures may be applied that do not address the underlying deficit. For example, if the child does not understand when the parent says, “clean up ,” time-out will not have the desired effect of increasing “compliance” on the next teaching opportunity. The child will still not know how to respond to the instruction, “clean up,” leading to continued faulty interactions between the parent and child.

2.1.3 Restricted Interests

The number or potency of preferred activities and reinforcers may be limited for children with ASD. This can create challenges with the child’s willingness to engage with items that the caregiver provides during a play activity —especially given the limited toys suggested for use during PCIT. For example, a child with ASD may only be interested in playing with clocks. This child’s parents might initially find it difficult to build meaningful interactions around the topic of clocks in play situations. However, if other activities are presented that are more appropriate but not of interest to the child, it will be difficult to establish a connection through naturalistic, positive play interactions for the dyad.

2.1.4 Stereotypic Behavior

ASD is also characterized by high rates of stereotyped behavior (which has its own specific challenges). If the child has low rates of appropriate play and high rates of stereotypy with toys, parental imitation of the child’s behavior, behavioral descriptions, and labeled praise can all be significantly impacted. Specifically, it might be contraindicated to draw attention to the stereotypy (e.g., “Nice job spinning the wheel”). Thus, the parents may hesitate to engage in play when they are unsure if the behaviors exhibited by their child are appropriate for fear of inadvertently reinforcing the play with attention. The child’s play skills (or lack thereof) may be influencing the parent’s confidence in joining in and modeling appropriate play skills .

2.1.5 Caregivers of Children with ASD

Clinicians using PCIT should expect to experience or witness unique challenges in their sessions. For example, the child may rarely initiate with caregivers, preferring to play alone. The child may even become upset when the caregiver attempts to insert him or herself into the activity by narrating, imitating, or joining in the play. Caregivers may ask their child too many questions or give a high number of commands that are outside of the child’s repertoire of skills; this may be in effort to fill the silence during a time the child is not engaging or communicating.

Many caregivers may feel worn or saddened by their child’s lack of engagement. Common questions from families of children with ASD include, “Why won’t my child play with me? I try and it just irritates him/her, so I have stopped,” or “Why would I play with my child when he/she doesn’t seem to like it?” A clinician may hear additional comments like, “I don’t know how to talk to my child because he/she doesn’t respond or doesn’t seem interested in what I am saying.” Often due to a lack of social reciprocity indicative of the ASD diagnosis, it may be common to observe caregivers looking uncomfortable with their children during play or for the play to look somewhat forced or unnatural. It is important for a clinician to remember that this does not indicate a lack of motivation or effort by the caregivers. Instead, these observations are likely due to a history of failed attempts at getting a reciprocated response from the child and a lack of resources to help the parent persist and/or adjust strategies under these circumstances .

2.2 Rationale for Use of PCIT with ASD

Although these unique issues may exist, educating and coaching caregivers on effective methods to enhance their child’s play, increase communication and compliance, and reduce disruptive behaviors can easily be incorporated into a standard PCIT approach. Further, these parent-child interaction skills may be critical to long-term development. Research has shown that interventions targeting adult responding can positively affect the social feedback loop (Yoder & Stone, 2006). PCIT focuses on teaching caregivers to attend to and respond positively to their children’s communicative attempts by providing praise, reflections, and behavior descriptions. In addition, the treatment emphasizes giving clear directions and following up consistently. These standard elements of PCIT are similar to interventions found to be useful when working with children with ASD. However, PCIT in its standard form may have limited utility for addressing the unique barriers of working with children with ASD , requiring some thoughtful adaptations.

3 Case Study Example

Two case studies on adapting PCIT for children with ASD will be discussed in this section. Findings are based off of our manuscript (Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016). In the study, two children diagnosed with ASD (i.e., “Devon,” a 3.5-year-old male, and “Cameron,” a 2.5-year-old male) participated in weekly sessions with their caregivers at a language clinic. Both participants presented with language and social skill deficits and were evaluated by a licensed psychologist at the center. Following a face-to-face intake with a clinician in the skill acquisition clinic and caregivers expressing concerns about noncompliance and/or challenges with playing or interacting with their child, it was determined that these children and caregivers would benefit from PCIT.

3.1 Pretreatment

Caregivers expressed to the therapist that they were experiencing challenges engaging in play with their children; this was congruent with direct observations. During the pre-assessment , Devon’s caregiver primarily asked questions and delivered demands that Devon either did not comply with or did not have the prerequisite receptive language skills to follow. Devon did not reciprocate when his caregiver made attempts to engage with him through play or conversation.

During the pre-assessment , Cameron’s caregiver was generally quiet. However, when she spoke, her interactions with Cameron consisted of commands and questions. Cameron’s caregiver rarely provided labeled praises, reflections, or behavior descriptions. She was observed to have difficulties engaging with him during the play session, and he did not reciprocate her attempts.

3.2 CDI

The CDI phase of PCIT focused on building positive parental behaviors in the context of play with the child. Some adaptations were made to typical CDI procedures (mentioned briefly here and in-depth in the next section) to address the family’s unique needs. The caregivers were taught to specifically assess their child’s preferences for items and activities and to incorporate these items in the sessions. Caregivers used several strategies to promote vocalizations and eventually taught their children to make requests. Mastery criteria for the CDI phase was altered, as it was noted that the children were not always vocalizing at a high enough rate for the caregivers to reflect 10 times per during the five-minute coding period. Thus, parents were required to meet two of the three criteria for positive caregiver behaviors: 10 reflections, 10 statements of labeled praise , or 10 behavior descriptions.

3.3 PDI

The PDI phase of PCIT focused on teaching parents to provide effective commands and implement a structured discipline procedure when met with child noncompliance. Again, some adaptations were necessary in this phase to increase the effectiveness of the procedure and ensure child understanding. The caregivers were taught to wait until the child displayed an indicating response for an item or activity before presenting the demand. Once interest in an item or activity was exhibited, the caregivers were trained to give one, clear instruction to their child. If compliance was observed, the parent provided a labeled praise and access to the desired item or activity. If their child did not comply within 5 s of the demand, rather than issue a warning statement or time-out, the caregivers were taught to use a three-step compliance procedure . Within and across PDI sessions, parents learned how to gradually increase their demands; for example, caregivers worked with their children on picking up just one toy to eventually cleaning up all toys in the room over the course of a session. Mastery criteria for the PDI phase was to give at least four commands (75% of which were single, direct, and positively stated) and provide the child an opportunity to comply. In addition, they had to have 100% follow through with the three-step guided compliance procedure .

3.4 Outcomes

Devon and Cameron participated for 13 and 14 weeks in treatment, respectively. Results showed that for both caregivers and their children, the intervention led to increases in desired behaviors during a five-minute coded behavioral observation. For Devon’s caregiver, parent positive behaviors, including labeled praise statements, behavior descriptions, and reflections, increased from the pre- (n = 9) to the posttreatment (n = 54) session. Similarly, for Cameron’s caregiver, parent positive behaviors increased from the pre- (n = 3) to the posttreatment (n = 45) session.

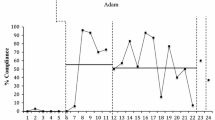

For Devon’s caregiver, parent negative behaviors , including questions, commands, and criticisms, also reduced from pre- (n = 65) to posttreatment (n = 7). For Cameron’s caregiver, parental negative behaviors continued to occur, but only at moderate levels (n = 18). In our study, we included measures of child vocalizations during pre- and posttreatment (Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016). Results showed a substantial increase in these behaviors (Devon: Pre = 18, Post = 48; Cameron: Pre = 5, Post = 30), suggesting that PCIT may be a viable approach to target vocalizations for children with ASD (Figs. 26.1 and 26.2). Below, all adaptations to the PCIT protocol are described in greater detail.

4 Adaptations to the PCIT Protocol for Children with ASD

In this section, the modifications made to standard PCIT will be described in greater depth. Additionally, step-by-step instructions are provided in Table 26.1.

4.1 Recommended Procedures: Environment

4.1.1 Preference Assessments

It has been hypothesized that deficits related to social motivation can account for many of the challenges that individuals with ASD face over their lifetimes (Chevallier, Kohls, Troiani, Brodkin, & Schultz, 2012). Expecting children to be motivated by social attention or interaction may not work if social interaction is not currently functioning as a reinforcer for desired behavior. Thus, positive parent behaviors alone may not be reliably counted upon as reinforcers for children with ASD during PCIT. Instead, parents may need to identify what items and activities are currently preferred by their children, and then use these items to reinforce their child’s desired behaviors. While this can be an effortful exercise , failure to identify potent reinforcers for child behavior can impede meaningful treatment improvement, thus putting the parents’ behaviors effectively on extinction. In other words, the parents may lose steam during CDI because little to no change is happening with their child. Thus, use of preference assessments (whether formal or informal) is a critical component of PCIT success for children with ASD and their caregivers.

In our study with Devon and Cameron (Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016), we drew upon a rich body of literature related to intervention with individuals with disabilities. We explored which toys and items were preferred by the children before initiating treatment. Adjustments in available activities or items were also made based on child preference throughout the course of treatment sessions. Decades of research support the contention that an individual’s preferred items are likely to function as reinforcers during skill teaching programs (Carr, Nicolson, & Higbee, 2000; Roane, Vollmer, Ringdahl, & Marcus, 1998). Preference for items can be evaluated in a number of ways, varying in complexity depending on the needs of the individual.

These procedures generally start by developing a list of items and activities that are likely to be of interest to the child. In the cases of Devon and Cameron (Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016), we used a parent interview based on the Reinforcer Assessment for Individuals with Severe Disabilities (Fisher, Piazza, Bowman, & Amari, 1996). In this interview, Devon and Cameron’s parents were asked a series of questions about potential preferred items; this allowed us to have a foundation of potentially reinforcing items to increase the likelihood of immediate child interest.

Next, the individual’s actual preference for these items was evaluated in a systematic manner. Roane et al. (1998) assessed preference by presenting individuals with disabilities with an array of eight items on a table and simply measuring the duration of engagement with each item during a five-minute observation session. Entitled the free operant preference assessment , this assessment is a reliable method in identifying reinforcers during subsequent evaluation periods. In the Carr and colleagues study (2000), children with ASD were also presented with an array of eight items and instructed to pick one. Once an item was selected, the child was allowed 10 s to interact with the item. When that time was up, the item was removed from the array, and the child was then instructed to select another item to interact with from the remaining seven objects. This process was repeated until all the items had been selected, and the order in which the items were selected was recorded. This very brief preference assessment, referred to as a multiple stimulus without replacement , aids in the identification of items that are the most likely to be effective reinforcers during skills training exercises. While these are just two examples of strategies to assess preference, clinicians may find these approaches easy to integrate into PCIT sessions for children with ASD.

For Devon and Cameron, we used a simplified version of the preference assessments described above. After the list of preferred items was generated, the items were set up throughout the therapy room, and parents were directed to briefly observe which toys their children engaged with most frequently. Additionally, the parents were taught to offer their children choices of items and note which items were selected most regularly. The “highly desired” items were then incorporated into all the PCIT sessions. For clinicians wishing to implement this modification to PCIT, see Table 26.1.

4.1.1.1 Common Concerns

Children with ASD can have rote and restrictive interests ; thus, PCIT clinicians may need to help parents strategically expand the list of possible items to present to the child over time. If a child presents with a very particular interest, say in Thomas the Train videos, the parent may be a little perplexed as to how to appropriately incorporate this video into their CDI interactions. Beginning with the known, powerful reinforcer, the clinician may want to evaluate the child’s response to related items that have similar properties. For example, perhaps a Thomas the Train puzzle or book may be appealing to this child. Also, if the child likes Thomas, they may enjoy playing with a wooden train set. With the parent, the clinician can brainstorm lists of items that may also strike the child’s interest; it is important for the clinician to then evaluate the child’s response to the items. Again, if the child engages with the new items or picks them when offered, we can assume these items may function as reinforcers (for at least a brief period of time).

4.2 Recommended Procedures: CDI

4.2.1 Indicating Responses

While preference assessment procedures are useful to generally identify possible reinforcing items for the child during PCIT sessions, the determination of which exact item or activity is most desired from moment to moment requires an additional assessment procedure. In our sessions with Devon and Cameron (Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016), we taught parents to look for specific behaviors that suggested their child was interested in a particular item or activity at that moment. These behaviors varied for each child but could take the form of: reaching for an item, pointing at an item, gazing at an item, attempting to independently manipulate an item, or standing near an item. The occurrence of these behaviors, collectively referred to as indicating responses , highlighted the child’s motivation for that item/activity within that moment. Parents were taught to identify what types of indicating responses their child used and when an indicating response occurred; the parent used this as an opportunity to teach their child to vocalize or request.

If no indicating responses were observed, parents were instructed to hold off from teaching communication and focus on contriving motivating situations for their child. The parents could contrive motivation by (a) modeling use of a toy (e.g., pushing the buttons of a toy piano so their child could see the lights and hear the sounds), (b) providing some parts of a toy to their child but withholding the rest (e.g., give two puzzle pieces but keep the other three), or (c) offering a small piece of a snack (e.g., a tiny piece of cookie while keeping the rest of the cookie). When an indicating response occurred, the parents would teach communication, provide reinforcement, and start the process over again . For specific implementation instructions, see Table 26.1.

4.2.1.1 Common Concerns

Children with ASD may demonstrate odd or unusual behaviors that are not as easily recognized as indicating responses. For example, a child may return to a location where a desired activity was provided on the day before. The indicating responses may be difficult to discern. For example, a child may wave at a pile of objects rather than specifically pointing at items. Or, challenging behaviors may be the only indication a child desires an item or activity. For example, a child may cry when a parent removes an item the child desired. In these instances, it may be useful to first teach the child to use a conventional gesture (e.g., pointing, reaching) to indicate interest. The responses would be immediately followed by access to the desired item or activity initially. Once these responses were established, other forms of communication could be taught.

4.2.2 Stimulus-stimulus Pairing

The typical components of the CDI training phase for caregivers may not always be suitable for children with ASD, particularly when rates of child vocalization are low. Parents may find it difficult to engage in social interactions with their child when the child cannot communicate in a conventional manner.

In the examples of Devon and Cameron, we trained caregivers to implement a strategy referred to as stimulus-stimulus pairing (SSP) during their sessions (Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016). SSP procedures are designed to associate the parents’ vocalizations with previously established reinforcing items and activities. It is believed that this repeated pairing may help to condition the parents’ vocalizations as reinforcers (Sundberg, Michael, Partington, & Sundberg, 1996), with numerous possible benefits. First, if the parents’ vocalizations are conditioned reinforcers, the children will attend to their parents more often. This increase in attention to parents could lead to cascading improvements for children’s overall skill development as they may begin to follow their parents’ directions and cues more readily (Hart & Risley, 1995). Secondly, as the sounds of parental speech become strong conditioned reinforcers, when the children vocalize and hear their own speech sounds, the similarity between their speech and their parents’ speech may also be reinforcing (Skinner, 1957; Sundberg et al., 1996). For example, a child says, “Uppa,” and the child recognizes that this sounds similar to when Mom and Dad say, “Up,” a sound which was previously associated with reinforcing activities such as being picked up. As the child comes to enjoy hearing her own speech (because it sounds like her parents’ speech and her parents’ speech has been associated with other enjoyable events) she may speak more. Additionally, if the child says, “Uppa,” and the caregiver responds by picking her up, this may further reinforce the vocalization as the child was able to obtain a desired behavior from her parent. These interconnected reinforcement pathways are believed to play a major role in the development of vocal speech in typical children.

During the SSP procedure, caregivers are encouraged to pair words and engagement with preferred items and activities. In the case of Devon and Cameron, caregivers were instructed to focus on words that most directly matched the items and activities their child was indicating interest in, therefore laying a foundation for future request training (Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016). Caregivers started by labeling the reinforcers as they gave them to their child (regardless of whether or not the child had vocalized). To increase the number of pairing opportunities between the word and the reinforcer, parents were encouraged to label the reinforcer: (1) as soon as they observed an indicating response, (2) as they delivered the reinforcer, and (3) as their child consumed or played with the reinforcer. For example, (1) as the child reached for his cup, the caregiver would say, “Drink”; (2) as the caregiver delivered the cup to the child, the caregiver will say, “Drink”; and (3) as the child took a sip from the cup, the parent would say, “Drink.” After repeating this process on several occasions, caregivers were encouraged to label the reinforcer, then pause, to allow the child to echo the word. For example, (1) the parents might say, “Drink,” as they saw their child reach for the cup but (2) wait a few seconds before delivering the cup to the child. If the child were to attempt an echo their parent, (3) the caregiver immediately and enthusiastically gave the cup while labeling it (“Drink! Here’s your drink”). If the child did not respond, the parent would give the item and label it as he/she delivered it and as the child consumed it, as before.

We often used this method in early stages of Devon and Cameron’s treatment (Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016). As the children made more frequent attempts at echoing, the caregivers were coached to delay giving the desired item and provide a more explicit opportunity for the student to echo. Consistent echoing by children was met with parental differential reinforcement. Specifically, successfully echoed trials resulted in access to the reinforcer and praise, but failure to echo resulted in minimal or no access to the reinforcer for a brief time until a new trial was initiated. These procedures allowed the caregivers to teach Devon and Cameron new vocal skills while simultaneously maintaining the quality of the parent-child interaction during the CDI phase. Importantly, SSP procedures usually begin with noncontingent reinforcement, so there are no specific demands in place to vocalize. Additionally, the inclusion of a brief delay before delivering a reinforcer allows the child an opportunity to independently vocalize, without specifically demanding speech. Thus, these features of SSP make it a useful component of the CDI phase for parents of children with ASD. See Table 26.1 for details.

4.2.2.1 Common Concerns

Parents may be tempted to immediately use contingent reinforcement procedures when they hear their child begin to echo. They may also be tempted to do only contingent trials, ceasing to do the trials without demands. If this jump is made too quickly, this could undermine the overall effectiveness of the procedure and could result in CDI becoming aversive. If this occurs, it can be useful to give the parents specific reinforcement ratios to aim for during their sessions. In other words, clinicians should instruct and guide parents to do noncontingent trials for 75% of the vocalization attempts and only use contingent trials on the other 25%. As clinicians observe improvements in a child’s responses, clinicians can choose to coach the parent to gradually shift the ratios (e.g., 50% noncontingent and 50% contingent, 25% noncontingent and 75% contingent).

4.2.3 Mand Training

Another important adaptation we incorporated into our work with Devon and Cameron (Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016) was the inclusion of procedures to teach requesting, also known as manding in the behavior analytic literature (Skinner, 1957). While Devon already had a well-developed echoic repertoire when he began the study, Cameron was largely nonverbal and did not consistently echo his caregiver’s vocalizations. With use of the SSP procedures outlined previously, Cameron began to consistently echo, making a transition to mand training an appropriate option.

As we previously discussed, caregivers were instructed to continuously assess their child’s motivation throughout sessions. Once the transition to mand training began, when an indicating response occurred, the parent was instructed to withhold the item for approximately 2 s without vocalizing. This allowed the child an opportunity to independently mand for the desired item. If the child vocalized or attempted to vocalize the item’s name, the caregiver immediately provided access to the item, labeled the item, and praised the child’s mand. For example, when Cameron reached for his cup, his caregiver withheld the drink and waited. When Cameron said, “Drink,” his parent immediately said, “Drink! Great job asking for drink,” as she handed him the cup. Occasionally, Cameron would not vocalize or would emit an approximation that was less than optimal. In this case, his parent modeled the name of the item then waited another 2 s for him to echo again. If Cameron was able to echo this time, the caregiver provided access to the item, labeled the item, and praised Cameron’s mand. Caregivers were directed to repeat this process as long as their child remained interested in the item without becoming visibly frustrated (e.g., engaging in precursors to problem behavior).

Parents of Devon and Cameron were instructed to use differential reinforcement procedures and monitor the degree of independence displayed by their children. For example, Cameron responded on the echo trials but did not respond on the independent trials initially; therefore, the echoed responses were considered his best responses and were reinforced. However, once Cameron was able to mand independently, only independent responses were reinforced because these were now considered his best efforts. Standards for the boys’ responses continued to increase over the course of treatment. Once independent responses were reliably observed, parents were instructed to reserve reinforcement for only the highest quality independent responses. For example, Devon started out by independently approximating “drink” by vocalizing, “Drah.” This statement was therefore reinforced. However, once Devon was observed to say “Drin-kah,” only this response was reinforced by his parents. This process continued until the child’s best approximation was the target sound/word. See Table 26.1 for detailed steps on implementing mand procedures.

4.2.3.1 Common Concerns

During early mand training, it is very important for parents to ensure that indicating responses and mands correspond with one another. If the child is observed to indicate for one item but say something else, the parent should correct this as an error by providing a model prompt of the correct word. For example, if the child reaches for chip but says “Drink,” the parent should prompt the child to say, “Chip,” then give the child the chip.

4.2.4 Reflecting Vocalizations Plus Pairing

Reflecting vocalizations is one of the key skills taught in CDI within standard PCIT procedures. Research has shown that responding to the vocalizations with either an imitation of the sound (i.e., reflection) or general motherese (i.e., speaking with an animated voice and exaggerated facial cues) increases children’s vocalizations (Pelaez, Ortega, & Gewirtz, 2011). We hypothesize that these procedures are effective because social responsiveness functions as a reinforcer for the child. However, for many children with ASD, social stimuli fail to become conditioned as reinforcers early in development (Dawson et al., 1998; Dawson et al., 2004). Therefore, simply coaching parents to echo speech sounds emitted by their child may not always result in an increase in vocal speech for children with ASD.

In our case studies with Devon and Cameron, we addressed this issue by modifying the parental directions for reflecting (Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016). Specifically, we encouraged parents to reflect the children’s vocalizations and to present an established reinforcer as they did so. For example, as the child said, “Baa,” the parent would also say, “Baa;” then the parent would provide their child with a yummy cracker. This process served two possible purposes: (1) to provide a reinforcer (e.g., the cracker) after a vocalization, thus increasing the future frequency of vocalizations, and (2) to increase the instances of pairing between the reinforcer and parent vocalization , a parallel strategy used in the SSP procedure. Activities such as tickles, hugs, or spins could all be quickly paired with the parent’s reflection of their child’s vocalization.

4.2.4.1 Common Concerns

Vocalizations of children with ASD may not always be appropriate, adding another complication to typical PCIT procedures. Children with ASD may engage in rote, repetitive vocalizations that have no bearing on the actual context. These vocalizations (often referred to as vocal stereotypy) are not desirable behaviors and should not be reinforced. Parents must be taught to discriminate between appropriate vocalizations and vocal stereotypy, and only reflect the appropriate vocalizations.

Children with ASD may also only emit approximations of words, making parents hesitant to reflect the vocal speech attempts. In these situations, parents should be educated that these vocalizations are appropriate, should be reflected, and should be reinforced when they occur. Some discussion of the phases of speech development may be helpful for these families so they can reconcile the difference between chronological and developmental norms. In other words, clinicians should be mindful in working with a family to help them understand that while the child’s typically developing peers may not repeat only simple consonant-vowel-consonant blends, this is a developmentally appropriate skill for their child with ASD. Refer to Table 26.1 for the procedures to implement this approach.

4.3 Recommended Procedures: PDI

4.3.1 Demand Fading

The PDI phase of PCIT emphasizes the importance of learning how to use commands effectively (e.g., developmentally appropriate, singular, stated directly). Often, parents referred to PCIT are unaware of the demands they place on their children. PDI teaches parents to deliver appropriate commands while continuously providing CDI skills (e.g., praise, reflections, behavior descriptions), therefore reducing the frequency of delivered commands and filling the remaining time with positive attention for appropriate behaviors. To further emphasize this skill, we included an antecedent strategy in the cases of Devon and Cameron called demand fading (Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016). In a demand fading procedure, the frequency of demands is significantly reduced from the outset of the session due to the disruption caused by a high level of problematic behavior (Pace, Iwata, Cowdery, Andree, & McIntyre, 1993; Shillingsburg, Hansen, & Wright, 2018). Similar to the standard PCIT procedure, the low rate of commands is hypothesized to reduce the child’s feelings of aversion during the interaction time with the parent. Shillingsburg et al. (2018) found that when demands were presented at a high rate during initial skill teaching sessions, proximity to the instructor remained low and the rate of problematic behaviors was elevated. However, when demands were removed and instructors focused on pairing skills (highly similar to the CDI strategies), proximity increased and problematic behaviors decreased. In treatment sessions, the instructor gradually reintroduced demands, with close monitoring of the participant’s willing engagement in the instructional activities and the instructor herself. Eventually, instructions were increased to the same levels as initially tested in baseline, but problem behaviors remained low and proximity to the instructor was high (Shillingsburg et al., 2018).

With Devon and Cameron, we chose to use this demand fading approach in the PDI phase, in the hopes that the gradual introduction of demands would not “undo” the progress made by the parent and child in the CDI phase (Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016). Initially, the clinicians asked the parent to target clean-up of just one toy. As compliance was observed, the number of items required was increased. As the initial demands were short and relatively simple to complete, the clinicians hypothesized that they were unlikely to be aversive to the children; therefore, this reduced the likelihood of problem behavior occurring to escape the task. As the children built a history of reinforcement following compliance, demands were extended without a return to problematic escape behavior. Additionally, the caregivers were taught to wait for an indicating response prior to presenting an initial demand, thus ensuring the student was motivated to earn an item or activity (Table 26.1).

4.3.1.1 Common Concerns

Parents may be tempted to present demands more frequently. It is important to remind parents to move slowly and systematically to achieve their long-term goals.

4.3.2 Errorless Prompting

Important differences are present when working with children with and without ASD in PCIT during PDI. While noncompliant behavior can serve a variety of functions for all children, special considerations need to be taken into account when working with children on the spectrum. For children with ASD, it cannot always be assumed that the child is capable of performing a desired demand made by a parent; what may look like noncompliant behavior may actually be a skill deficit. Determining the difference is critical for parents and clinicians, as each requires a different approach. Thus, for clinicians conducting PDI sessions for children with ASD, the standard list of commands may not be appropriate to use. In addition, age-appropriate questions may not be developmentally appropriate for the child if developmental delays are present. Clinicians and parents should work closely together to create a list of demands that the child most frequently complies with, which can be considered mastered or known. Failure to comply with these commands would be treated as noncompliance, while other responses would be considered unknown or unmastered skills (instead addressed through errorless prompting strategies).

Errorless prompting strategies generally consist of using a reliably effective prompt (e.g., a gesture prompt, a model prompt) which is then followed by reinforcement. Over time, the prompts are altered to be less intrusive and slightly more challenging to the child. One of the simplest prompting strategies that parents can learn to apply in PCIT sessions is graduated guidance . Graduated guidance requires the parent to present an instruction and then manually guide the child to complete the task (MacDuff, Krantz, & McClannahan, 2001). As compliance with prompting is observed, the parents may lessen the amount of aid necessary to prompt the child to comply. For example, Devon’s mother needed to initially guide Devon to pick up a toy using a hand-over-hand prompt; however, she was eventually able to simply nudge Devon’s upper arm to prompt him to pick up the toy.

Graduated guidance strategies typically include a shadowing step where the parent does not touch their child, but their hands remain close if immediate prompting is needed. Eventually, the child may pick up the toy without any additional prompts from the parents to do so. Using these strategies, parents can teach their child to perform new skills (a critical component of interventions to support individuals with ASD). Please refer to Table 26.1 for more information on this adaptation.

4.3.2.1 Common Concerns

Skills that have not been mastered may be relatively difficult for the child. As excited as parents may be to see their child learn a new skill, repeated presentation of difficult demands may be inadvisable for PCIT sessions. Thus, clinicians may need to encourage parents to alternate between unknown and known demands to keep the child from being pushed past his/her threshold.

4.3.3 Three-step Prompting

While we were able to teach parents how to use errorless prompting strategies to build unknown skills , we were also able to teach parents how to address noncompliant behavior related to known skills. Typical PCIT procedures train parents to provide more effective instructions and implement a structured discipline procedure. While this is still an important step for parents of children with ASD, additional methods were utilized with Devon and Cameron’s families (Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016). Noncompliant behavior was also addressed using the three-step prompting method (i.e., verbal prompt, model prompt, physical guide; Miltenberger, 2001; Tarbox, Wallace, Penrod, & Tarbox, 2007). In this procedure, when noncompliance with a known skill was exhibited, the caregiver was taught to first repeat the demand verbally (e.g., “Put your toy in the bin”). After 5 s, if the child did not comply, the caregiver modeled the skill for the child (e.g., parent repeats, “Put your toy in the bin,” while modeling how to put the toy in the bin, and then says, “Now you do it”). After another 5 s, if the child still did not comply, caregivers used a physical guide to help the child complete the command (e.g., parent repeats, “Put your toy in the bin,” and physically guides the child to comply). In addition to the three-step prompting, differential reinforcement procedures were used in which parents reserved praise and access to the desired items/activities for when the child complied after either a verbal or model prompt only.

The three-step prompting procedure is frequently used in applied behavior analysis training programs (the gold-standard evidence-based treatment method for youth with ASD) to minimize the likelihood of a child receiving any reinforcement after noncompliance. Noncompliance can have several functions for children. First, noncompliance may function as a form of escape from instruction therefore producing reinforcement through avoidance of undesirable demands. When this is the case, three-step prompting prevents the child from escaping, effectively placing noncompliance on extinction. Second, noncompliance may also function as a means to access parental attention. In these scenarios, three-step prompting teaches parents to remain calm and avoid providing attention following instances of child problem behavior. By refraining from providing possibly reinforcing forms of interaction (e.g., reprimanding, consoling), the parent is also reducing the likelihood noncompliant behavior will occur again. Third, by using differential reinforcement strategies for compliance, the child is only receiving tangible and social reinforcement when he or she complies with verbal or model prompts. This may prevent the child from developing a history of dependence on intrusive parental intervention (e.g., manual guidance). Also, the child will understand that fun activities and praise are only accessible with independence. Function-based interventions are a common component of interventions for individuals with disabilities (Hanley, Iwata, & McCord, 2003). Three-step compliance is a simple but effective approach for parents of children with ASD in PCIT (see Table 26.1).

4.3.3.1 Common Concerns

As soon as parents observe compliance with their child, they may be tempted to rapidly increase the rate of demand presentation. Coach them to be patient and mindful of the current demand fading step.

5 Conclusion

There is increasing research support that PCIT can improve parent-child interactions, problematic behavior, and language skills (Eyberg, 1988; Solomon et al., 2008). Utilizing PCIT with the ASD population may help increase access and outreach of services to children and their families. While many generalist psychologists have experience and familiarity with PCIT and/or other manualized parent-training interventions, these clinicians may not have expertise in the area of behavior analysis or children with ASD, in general. Adapting a widely used evidence-based intervention to implement with children with ASD better equips professionals to adequately deliver an intervention without starting from scratch. This method is beneficial for both providers who want to address the needs of their clients with ASD and families who live in rural areas and may not otherwise have access to specialized care.

Unlike some other treatment models for children with ASD, PCIT focuses on improving a caregiver’s ability to serve as a change agent; this allows a child to receive more hours of intervention outside of a clinic, and it increases the likelihood that positive gains can be generalized to the natural environment. Parent-training programs are also a less intensive form of intervention than many treatment options for children with ASD. Parent-training programs such as PCIT add to the diversity in client treatment options for families with differing abilities, time, and available resources. Lastly, intensive services can be quite expensive to deliver. A modified version of PCIT may prove to be an effective evidence-based intervention at a lower cost.

Many of the experiences that parents have described relating to the difficulties in engaging and teaching their children with ASD can be alleviated through adapted PCIT. Our clinical findings for Devon and Cameron yielded high levels of parental-reported satisfaction; acceptability of treatment; and effectiveness of the intervention for addressing child language development, behavioral functioning, and the parent-child relationship. In addition to the caregiver report, we noted several positive changes in the caregivers’ behavior and in the parent-child interactions during the behavioral observations (Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016).

Prior to starting PCIT, caregivers expressed discomfort, awkwardness, and difficulty when asked to play with their child. Over the course of treatment, there were clear changes in parental behavior and child response. In both families, their interactions appeared much more natural. Caregivers were better equipped to deliver praise and behavior descriptions, model appropriate play, provide opportunities for the child to engage in the activity, introduce novel toys and activities, and assess their child’s preferences.

Overall, PCIT is a promising tool for improving parent-child interactions and decreasing child maladaptive behavior. We are some of the many clinicians and researchers who have firsthand experience in witnessing the positive impact of educating, coaching, and empowering caregivers to be change agents for their children with ASD (Hansen & Shillingsburg, 2016; Solomon et al., 2008). Investigating and refining the procedures for applying PCIT with children with ASD and their families is an ongoing endeavor. Through this work, PCIT can continue to improve community outreach and access to services for families, provide an additional service on a continuum of intensity, and improve the generalization of child outcomes.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Anderson, D. K., Lord, C., Risi, S., DiLavore, P. S., Shulman, C., Thurm, A., & Pickles, A. (2007). Patterns of growth in verbal abilities among children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(4), 594.

Carr, J. E., Nicolson, A. C., & Higbee, T. S. (2000). Evaluation of a brief multiple-stimulus preference assessment in a naturalistic context. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33(3), 353–357. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2000.33-353

Chevallier, C., Kohls, G., Troiani, V., Brodkin, E. S., & Schultz, R. T. (2012). The social motivation theory of autism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16, 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.02.007

Dawson, G., Meltzoff, A. N., Osterling, J., Rinaldi, J., & Brown, E. (1998). Children with autism fail to orient to naturally occurring social stimuli. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 28(6), 479–485.

Dawson, G., Toth, K., Abbott, R., Osterling, J., Munson, J., Estes, A., & Liaw, J. (2004). Early social attention impairments in autism: Social orienting, joint attention, and attention to distress. Developmental Psychology, 40(2), 271–283.

Eyberg, S. M. (1988). Parent–child interaction therapy: Integration of traditional and behavioral concerns. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 10(1), 33–46.

Fisher, W. W., Piazza, C. C., Bowman, L. G., & Amari, A. (1996). Integrating caregiver report with systematic choice assessment to enhance reinforcer identification. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 101, 15–25.

Girolametto, L. E. (1988). Improving the social-conversational skills of developmentally disabled children: An intervention study. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 53(2), 156–167.

Greenwood, C. R., Thiemann-Bourque, K., Walker, D., Buzhardt, J., & Gilkerson, J. (2010). Assessing children’s home language environments using automatic speech recognition technology. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 32(2), 83–92.

Hanley, G. P., Iwata, B. A., & McCord, B. E. (2003). Functional analysis of problem behavior: A review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36(2), 147–185. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2003.36-147

Hansen, B., & Shillingsburg, M. A. (2016). Using a modified parent-child interaction therapy to increase vocalizations in children with autism. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 38(4), 318–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317107.2016.1238692

Hart, B., & Risley, T. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Jaffe, J., Beebe, B., Feldstein, S., Crown, C. L., & Jasnow, M. D. (2001). Rhythms of dialogue in infancy. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 66(2), 1–149.

Leezenbaum, N. B., Campbell, S. B., Butler, D., & Iverson, J. M. (2014). Maternal verbal responses to communication of infants at low and heightened risk of autism. Autism, 18(6), 694–703.

Lesack, R., Bearss, K., Celano, M., & Sharp, W. G. (2014). Parent–child interaction therapy and autism spectrum disorder: Adaptations with a child with severe developmental delays. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 2, 68–82.

MacDuff, G. S., Krantz, P. J., & McClannahan, L. E. (2001). Prompts and prompt-fading strategies for people with autism. In C. Maurice, G. Green, & R. M. Foxx (Eds.), Making a difference: Behavioral intervention for autism (pp. 37–50). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

McNeil, C. B., & Hembree-Kigin, T. L. (2011). Parent-child interaction therapy (2 nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer.

Miltenberger, R. G. (2001). Behavior modification: Principles and procedures. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thompson Learning.

Neary, E. N., & Eyberg, S. M. (2002). Management of disruptive behavior in young children. Infants and Young Children, 14(4), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001163-200204000-00007

Pace, G. M., Iwata, B. A., Cowdery, G. E., Andree, P. J., & McIntyre, T. (1993). Stimulus (instructional) fading during extinction of self-injurious escape behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26(2), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1993.26-205

Patten, E., Belardi, K., Baranek, G. T., Watson, L. R., Labban, J. D., & Oller, D. K. (2014). Vocal patterns in infants with autism spectrum disorder: Canonical babbling status and vocalization frequency. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(10), 2413–2428.

Paul, R., Fuers, Y., Ramsay, G., Chawarska, K., & Klin, A. (2011). Out of the mouths of babes: Vocal production in infant siblings of children with ASD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 588–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02332

Paul, R., Orlovski, S. M., Marcinko, H. C., & Volkmar, F. (2009). Conversational behaviors in youth with high-functioning ASD and Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(1), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0607-1

Pelaez, M., Ortega, J. V., & Gewirtz, J. L. (2011). Contingent and noncontingent reinforcement with maternal vocal imitation and motherese speech: Effects on infant vocalizations. European Journal of Behavior Analysis, 12, 277–287.

Roane, H. S., Vollmer, T. R., Ringdahl, J. E., & Marcus, B. A. (1998). Evaluation of a brief stimulus preference assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 31(4), 605–620. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1998.31-605

Sheinkopf, S. J., Mundy, P., Oller, D. K., & Steffens, M. (2000). Vocal atypicalities of preverbal autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 345–354. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005531501155

Shillingsburg, M. A. (2004). The use of establishing operation in parent-child interaction therapy. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 26(4), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1300/J019v26n04_03

Shillingsburg, M. A., Hansen, B., & Wright, M. (2018). Rapport building and instructional fading prior to instructional fading: Moving from child-led play to intensive teaching. Behavior Modification, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445517751436

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Solomon, M., Ono, M., Timmer, S., & Goodlin-Jones, B. (2008). The effectiveness of parent-child interaction therapy for families of children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1767–1776.

Sundberg, M. L., Michael, J., Partington, J. W., & Sundberg, C. A. (1996). The role of automatic reinforcement in early language acquisition. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 13, 21–37.

Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Bornstein, M. H., & Baumwell, L. (2001). Maternal responsiveness and children’s achievement of language milestones. Child Development, 7(3), 748–767.

Tarbox, R. S. F., Wallace, M. D., Penrod, B., & Tarbox, J. (2007). Effects of three-step prompting on compliance with caregiver requests. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40(4), 703–706. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2007.703-706

Warlaumont, A. S., Richards, J. A., Gilkerson, J., & Oller, D. K. (2014). A social feedback loop for speech development and its reduction in autism. Psychological Science, 25, 1314–1324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614531023

Warren, S., Gilkerson, J., Richards, J., Oller, D. K., Xu, D., Yapanel, U., & Gray, S. (2010). What automated vocal analysis reveals about the language learning environment of young children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 555–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0902-5

Yoder, P. J., & Stone, W. L. (2006). A randomized comparison of the effects of two prelinguistic communication interventions on the acquisition of spoken communication in preschoolers with ASD. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49, 698–711. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2006/051

Yoder, P. J., & Warren, S. F. (1999). Maternal responsivity mediates the relationship between prelinguistic intentional communication and later language. Journal of Early Intervention, 22(2), 126–136.

Zwaigenbaum, L., Bryson, S., Rogers, T., Roberts, W., Brian, J., & Szatmari, P. (2005). Behavioral manifestations of autism in the first year of life. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience, 23, 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.05.001

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Shillingsburg, M.A., Hansen, B., Frampton, S. (2018). Clinical Application of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy to Promote Play and Vocalizations in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Case Study and Recommendations. In: McNeil, C., Quetsch, L., Anderson, C. (eds) Handbook of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for Children on the Autism Spectrum. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03213-5_26

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03213-5_26

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-03212-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-03213-5

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)