Abstract

This chapter sketches out the inequities in higher education based on gender and more specifically the asymmetrical gendering of experiences and outcomes of students and faculty in higher education institutions in the Asia-Pacific region. Many of the gender issues are related to access, retention and completion and career progression; field of study, horizontal segregation by discipline and impact on academic career and postgraduation earnings; and the everyday experiences of students and faculty. The Asia-Pacific region is large and culturally diverse, comprising higher education systems at different levels of development. Thus, the manifestation of gendered inequity in different systems also varies significantly. The chapter reviews various policy interventions as advocated by international organizations. It also examines new concepts such as “gender fairness” and “gender borders” within higher education.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the major accomplishments of higher education (HE) across the Asia-Pacific region in the last three decades has been dramatically increased access (ADB 2011). Equity remains a different story. Gender is a marker of inequality which intersects with and compounds other categories of difference and disadvantage including (but not limited to) geography (rurality), ethnicity, and class/caste. Inequities in HE based on gender persist in the face of increased access with consequences for the full participation of women, as students and faculty, and with implications for the capacities of HE to serve its many stakeholders. This is notwithstanding significant efforts of governments and global policy agents such as UNESCO and the World Bank, and national governments and peak academic and disciplinary organizations to address issues related to gender inequity in access to and participation in HE. Gendered inequity and more broadly the asymmetrical gendering of experiences and outcomes of students and faculty in HE remain a persistent and under-researched issue in HE systems across the Asia-Pacific region. It is recognized by both the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and UNESCO as a major challenge for HE systems across the region.

In its 2010 Advocacy Brief, Gender Issues in Higher Education, UNESCO outlined the then-current state of gendered inequity noting that HE is not only a site for particular forms of gender inequality but also one in which the compounded effects of accumulated educational, socioeconomic, cultural, and geographic disadvantage also play out. In the same Advocacy Brief, the authors note that detailed understanding of the dimensions of the problem—and we would add its variation across the region—is hampered by the lack of national-level sex-disaggregated indicators in higher education and because there are:

few research-based studies on gender issues in higher education, an issue highlighted by UNESCO and the development and education community. The situation is particularly significant in the Asia-Pacific region – a region rich in the diversity of cultures, economic and human development, and gender relations. (UNESCO 2010, 1)

A useful starting point for addressing the more general gender question is the list of issues formulated by UNESCO, which we have amended slightly to encompass the experiences of faculty along with students in our focus as these constitute further points along the educational continuum where the “baggage” of compounded disadvantage takes its toll:

-

1.

Access, retention, completion, and career progression;

-

2.

Interface between gender and wealth-based disparities;

-

3.

Field of study, horizontal segregation by discipline, and impact on academic career and postgraduation earnings;

-

4.

The everyday experiences of students and faculty, including sexual violence and intimidation on campus and in the classroom;

-

5.

Texture of inequalities (adapted from UNESCO 2010, 1–5).

The presence or absence of women faculty in a wide range of roles, including leadership and research roles, and across all disciplines and fields sends important signals to both male and female students about how gender may be enacted within the academy. Full equity of access and opportunity will not only see women thriving in all fields of study alongside their male peers, but also see them with valid career paths from undergraduate through postgraduate study and into leadership roles in the academy without their “precipitous” departure at key career junctures (the transition to and from graduate degrees for example) or being marooned by any number of horizontal or vertical barriers to full participation. We consider that the inclusion of the gendered experiences of faculty is an important addition to UNESCO’s list of issues: To a large degree, the presence or absence of women faculty becomes a salient feature of the way in which students, irrespective of gender, experience HE.

Teasing Out the Issues

As is well documented, the contours and complexion of the impact of gender in HE systems may differ from system to system, reflecting local conditions, culture, and histories. The Asia-Pacific region is large and culturally diverse, comprising advanced HE systems, such as those in the USA, Australia, India, and Singapore, and rapidly developing systems. In some regional instances, participation rates of women students have reached or exceeded parity, while in others this is still some way off.

The persistence and ubiquity of gender inequality and inequity and asymmetrical gender differentiation have generated a rich array of metaphors and descriptors, but perhaps less by way of proven solutions to tackle the problem. Even where some problems are addressed, asymmetric gender effects have the capacity, it seems, to shift as one element—such as access—is addressed, another emerges. In this way, problems of equality of access, largely addressed in many HE systems in the region, have revealed the capacity to morph into other gendered problems such as assuring equity in full participation and opportunity. In terms of the professional advancement of faculty, we observe both sticky floors and glass ceilings; in relation to the participation of women in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics fields (STEM), we observe in some instances narrow and/or leaky pipelines as girls in many systems fail to take up STEM studies in school, or having pursued these studies, abandon them at key life-career junctures. In general, this is particularly the case for women STEM doctoral and postdoctoral researchers. Gender inequity is manifest structurally through both horizontal and vertical differences in the access, participation, experiences, and educational and career trajectories of men and women as students and as faculty.

Horizontal segregation of women and men is perhaps most marked in many systems by the clustering of women in humanities and social sciences, into the so-called “caring” professions of education, nursing and allied health, and where they do take up STEM studies, it is frequently in the biological and life sciences end of the spectrum, not in the hard sciences and technology fields such as engineering. This is largely due to pipeline effects—relatively low numbers of girls pursuing STEM at school and the persistence of gender stereotypes about what kinds of study and work are best suited to women and men, respectively. Although as we shall see, there are some notable and perhaps telling exceptions to this.

Horizontal segregation may also play out in the career choices, if indeed choice is the correct word, of academic women within HE. Irrespective of discipline or field, women faculty tend to perform a higher proportion of the burdensome administrative work and take on a larger proportion of teaching-related pastoral care work with potential impact on time for research and career trajectories. This produces a complex situation in which horizontal segregation intersects with vertical gender-based segregation as women fail to seek or receive advancement, while male colleagues whose capacity to do so is enabled by the disproportionate burden of teaching and administration borne by female colleagues, pursue research objectives, win grants, secure tenure, and ascend the university hierarchy. Another point at which the horizontal intersects with the vertical is in the area of grants, where, by and large, the largest sums are to be bid for in STEM, where women are underrepresented in many systems. Our intention in this chapter is to suggest a variety of generalizations that appear to “fit” the data relevant to the status of gender in higher education throughout the Asia-Pacific.

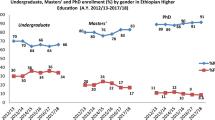

Access and Participation

One of the most commonly researched areas in gender and higher education is the issue of access and participation of female students in higher education. Quite a number of Asia-Pacific countries such as South Korea, Japan, China, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines have more female students enrolled in higher education than males, whereas others such as Cambodia, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Nepal have more male students (UNESCO 2010). Thus, gender inequality, be it for men or women, is an area of concern. To understand this gender gap in different contexts, to formulate appropriate policies, and to devise effective strategies to achieve gender parity in tertiary student enrollment continue to be of great interest to researchers, policymakers, and practitioners. Historically, much research has been focused on why there were fewer women enrolled in higher education, but less attention has been given to the more recent issue of why men are missing in higher education in an increasing number of countries.

Gender distribution in higher education remains a persistent issue. Even in countries where the Gender Parity Index (GPI) for tertiary education exceeds 1, women are underrepresented in the fields of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM fields). For example, in Malaysia even though 58% of recent tertiary education graduates were female, while 59% of the science graduates were female, only 36% of engineering graduates were (UNESCO 2015). Scholars are exploring the various factors contributing to these gender gaps and seeking effective policy solutions. Past research studies have shown that gender stereotyping especially in school curricula has resulted in women shying away from choosing a career in the STEM fields (UNESCO 2010). However, with the spread of manufacturing and the digital revolution throughout the region, more women may now view science and technical fields as viable career options. Statistics also show that women enrollments at the postgraduate levels are generally lower than those for males. To understand the emerging trends in gender gaps, we need more gender-sensitive educational statistics and indicators.

Women in Academia

Women’s underrepresentation in senior management in higher education institutions is another area of concern. What factors help to explain this phenomenon? Do recruitment and selection processes discriminate against women who apply for senior management positions? Is support and mentoring critical to creating and actualizing effective pathways into senior management? What are the skills required for effective higher education leadership and management? Do women and men have different management styles? Do gender and leadership styles impact on senior management? Does having women in senior management impact on decision making in, and the culture of, higher education? How powerful are Rectors/VCs/Presidents and do they have an impact on the gender composition of senior management team? These are some of the issues that have been commonly researched by researchers in different parts of the world (UNESCO 1993; Bagilhole and White 2011), albeit it with quite different results.

The literature on women’s participation in higher education leadership can be broadly grouped into four analytical frameworks, namely (i) gendered division of labor, (ii) gender bias and misrecognition, (iii) management and masculinity, and (vi) organizational exploitation and work/life balance challenges (Morley 2013). The fact that a primary women’s role is to care for children, the sick, and elderly often makes it difficult for them to take on the heavy responsibilities that come with senior management positions. Women academics are caught between two high levels of “institutional demands”—the extended family and the university. However, this argument does not explain why some women who are not so characterized (by being single or child/parent-free) are also not selected for higher education leadership. Research often indicates that gender bias exists in the recruitment and selection of higher education leaders, as the dominant group tends to appoint in its own image. Bias can exist at different stages of academic life, with women’s skills and competencies misrecognized. In many instances, leadership qualities such as assertiveness, autonomy, and authority are often associated with males, whereas females are more associated with qualities such as caring and effective communication. The suggestion that women and men have innately different managerial dispositions is highly problematic. The presumption that women lead differently creates binds for women who do not fit “the gender script.” More sophisticated frames of analysis are needed to make sense of the underrepresentation of women in higher education leadership.

It is observed, however, that women are now part of senior management in higher education to varying degrees in many countries. Nevertheless, overall the roles within higher education senior management tend to be gendered resulting in gendering of academic roles (Bagilhole and White 2011). The gendered segregation of management roles is manifested in women often being disproportionately recruited for jobs or committee positions that are time-consuming with heavy workloads in roles such as secretaries, deputy presidents, vice-chairs, or positions that deal primarily with student affairs. It has been posited that with changing times and the impact of the women’s movement, there may be differences in the career trajectories and experiences between senior groups of women academics and a younger cohort who are between early and mid-career stages (Bagilhole and White 2013).

No shortage of literature exists on how to change the situation of women in academia as described above. International organizations such as UNESCO, OECD, and the World Bank have produced multiple policy briefs on gender issues in higher education. Morley (2013, 10) has summarized one range of interventions as follows:

-

i.

Fix the women—enhancing women’s confidence and self-esteem, empowerment, capacity building, encouraging women to be more competitive, assertive, and risk-taking.

-

ii.

Fix the organization—gender mainstreaming such as gender equality policies, processes, and practices; challenging discriminatory structures, gender impact assessment, audits, and reviews; introducing work/life balance schemes including flexible working.

-

iii.

Fix the knowledge—identify bias, curriculum change, for example, introduction of gender as a category of analysis in all disciplines, introduction of gender/women’s studies.

Women Graduates and the Workplace

Although a higher level of education lowers or breaks down many barriers for women to enter professions that are/were dominated by men, gender stereotypes do not necessarily cease to exist. Meanwhile, the awareness that women in the search of professional careers should not necessarily shed their household duties is also on the rise. After a woman has survived the on-campus challenges as a female student, she is likely to be faced with bigger dilemmas from the “sticky floor and glass ceilings” in employment situations, from the expectation of marriage, partnering, birth giving, and child raising, and from the moral judgments placed on her balancing the demands of work and home.

The Production of Knowledge: Women’s Ways of Knowing

Literature on the goal of women’s studies identifies different levels of criticalness. Women can be the focus of new content and constitute a definitive lens to supplement the lack of women’s images in traditional disciplinary training that focuses on male protagonists—examples are women’s literature and women’s history which can deployed in pursuit of increasing women’s confidence and highlighting women’s culture. A second effort can be focused on a critique of the abstractness of the meta-narratives in which women are described as a collective with few personal traits, and readjust comprehensive disciplines, for example, sociology and anthropology to emphasize the significance of the individual and the micro. An even more critical goal is to empower individual women with an emphasis on the politics of the body. Involving the defense of the stigmatization of women’s bodies and femininity, the third aspect of acknowledging women’s way of knowing, takes active steps to resist the domination of men over women and of masculinity over femininity (Li 1995, 2–3).

No matter what the goals and ways of doing research about women are, these efforts implicitly or explicitly shed light on the politics of knowledge production: For what and by whom certain knowledge is produced. Taking the initiative to overtly produce knowledge from the reflection on and refining of women’s daily experience, women’s studies challenges the default (mis)conception that knowledge should be objective, neutral, and emotionless. This initiative may also challenge people to exit their comfort zone of thinking, being, and doing to reach out for individuals and communities living in other gender, racial, and class conditions.

Another crucial issue to consider is the impact that social media have on the ways and meanings of knowledge production. In particular, mainstream mass media are giving way to the variety of “new” media that are going beyond being simply tools to exchange thoughts and publicize information. More noticeably, they provide the ubiquitous and responsive “infrastructure” of interaction that conditions highly networked participation (Lievrouw 2011, 14–15). Arguably, characterized with the highly decentralized and grassroots-friendly authorship, the “new” media constitute an alternative space that may assist the creation and circulation of women’s ways of experiencing and knowing, which underpin the epistemological improvement of gender equality. The new pattern of virtual communication both demands and inspires spontaneous interaction and collaboration, if emergent consciousness and knowledge are to be known, learned, and used. Rapidly developing and renovated, the intervention of new media opens up unlimited discussions of how gender perspectives may refresh the understanding of what constitutes valid knowledge and whose interest knowledge serves.

Women and Nationality

For some Asian countries, such as China, the creation of a modern nation and the commencement of women’s education were intertwined and mutually influential processes. Both processes took place when capitalism was expanding to the East and stirred severe national insecurity and crises. When based on the “phantasm” of Western women (Zhu 2014), it was believed that a better-educated female population would be a positive contribution to national power in the future. Two other themes were emerging as well. One was to label women’s illiteracy and lack of education and physical strength as a major reason that kept the nation “backward” in comparison with the industrialized Western world. The result was that women “were to blame” in some complex way, which exempted men from their duty of reflecting on the pitfalls of a patriarchal society and perpetuated the habitual thinking of blaming the victim. The other theme was directed at the design of women’s new roles in relation to the nation’s future. Questions were asked, such as whether it was the “new women’s” duty to become qualified mothers of qualified male citizens in the future and therefore strengthen the racial seed; whether it is fair to attach the importance of women’s education to household responsibilities while that of men’s was to individual prominence; and whether meeting “national needs” should be a major, unquestionable assessment of the quality of education.

The rise of women’s education, however, did not only bring about a more skilled labor force to the needy nation, but also cast challenges to what was believed to be tradition as the category of “women” became dynamically associated with the complex concept of modernity. As apparent as the demographic change that has taken place in the public sphere since women’s participation, an awakened women’s subjectivity—especially the autonomy of body—inspired by a higher level of education collides with those portions of the national foundation that is comprised of patriarchy, patrilineage, and patrilocal tenets.

What Is/Might Be the Role of Gender “Workshops” Within Higher Education Institutions?

The increase of women’s studies programs on university campuses and the progress of gender awareness in higher education institutions are significant results of the many self-motivated attempts to highlight a women’s perspective on human rights. In Asia, as well as for the Asian diaspora worldwide, NGOs and individuals have created experimental workshops in a general effort to make more visible the urgency of reducing gender inequality. These workshops also seek to identify pedagogical patterns relevant to the teaching of feminism or gender knowledge that align with local cultures and/or targeted populations across geographical regions. The action of building workshops for gender equality can be seen as an integration of theory and practice that has a focus on women and sexuality and that supplements or redresses the role of formal, gender-blind higher education. Comparatively, such workshops are designed to be more responsive than universities to the impact on women that the rapidly changing demographics and technology in both education and labor market have.

Usually, such workshop organizers are conscious of both global trends of gender discourses and local socioeconomic, cultural, historical, and political characteristics. In addition, the organizers themselves are a product of hybridized higher education of different locales, which often includes the encounter between the East and the West. Hence, the space of gender workshops is a “glocal” one that simultaneously addresses the commonality of patriarchal discrimination to gender, race, and class across national borders, and facilitates constant re-examination of misogyny and gendered bias within particularly identified contexts (LeeAn 2009).

More…

Other ways of framing and phrasing various issues proceed from the above and are deserving of further attention, some of which will be touched on in the various chapters that follow:

-

New approaches such as that characterized by “gender fairness” which focuses on creating an enabling environment for the surrounding society.

-

Gender “borders” within higher education: What are they? Where do they come from? What are their effects?

-

Generation and gender in academia. How significant is this structure and the relationships that flow from it? What might be done to facilitate better inner-generational communication and collaborative research?

-

Female institutional leadership in Higher Education. How extensive is it? Are there significant or relevant differences in institutional leadership that can be identified within higher education roles? If so, what is their character and what consequences flow from them, etc.?

-

Nurturing and development of women studies. Where do women studies exist and where not? Are there useful explanatory models to account for such differences etc.? Can particular models be identified that might bear emulation?

These issues/subjects may be conceptualized as elements emerging from “older” elements/aspects of a comparative gender framework, by which we refer to issues that tended to be most evident in the decade after the turn of the century, and perforce were those that were most emphasized in the UN report referenced earlier in this chapter. In subsequent years what might appropriately be viewed as a set of “emergent” issues have arisen, often in the social space that has been created by the important fact that in various societies some earlier practices and policies affecting gender access to higher education have in fact succeeded. Such a perspective allows us to see that the road to gender equity is both long and complex. To illustrate, we suggest that the following may also be appropriate subjects for further study, perhaps gaining perspective by seeing them in a contrast between “older” issues affecting gender—with the important caveat that in many instances the inequalities represented persist—and a “newer” set of issues.

In many instances, these might be characterized as “new” more rapid nationalistic approaches in many nations in the region on the enabling nature of the surrounding society itself, e.g., patriarchal cultures, dominant family paradigms, including mothers who pressure daughters to study areas appropriate to women (e.g., education), pressure to get married and have children and grandchildren.

In many Asian nations as indicated above, enrollments of women are now approaching those of men and in some cases exceeding them such that access per se is not really the point, but rather attention should continued to be directed at fields of study, stereotypes, etc. most visible in the lack of women majors in STEM fields, etc. In this instance, desirable research might focus on the “enabling” or “inhibiting” factors within HE that encourage or dissuade women from entering those fields.

Men dominate fields such as engineering, manufacturing, and computer sciences, sometimes exceeding 80%, while women are concentrated in education, humanities, arts, health and welfare, etc. What kinds of factors exist to promote and/or sustain such pathways and are such patterns changing?

The recent focus on affirmative action, quota systems, aggressive recruitment of women faculty and administrators, reform of curriculum and teaching, etc. is part of the gender-fair model. Can we point to instances in which such enabling activities exist, and can we discern data that suggest the relative success of such policies and actions?

A new redefined role for “all women colleges” appears to be emerging as sites for further liberation of women career choices; family friendly campuses; time off for childrearing from the tenure clock, etc. Continued research can bring new and relevant comparative data to this emergent field.

The new emphasis on LGBT populations in women’s education and liberation has progressed rapidly in some settings. How are such population identities treated within the continuous expanded higher education community? Where do they gain organizational form within higher education?

Rejection to some degree of what the analysis of gender issues is in the West, and the search for cultural and historical appropriateness in Asian women’s higher education experience is a developing area of research. Scholars are increasingly asking: Where and how are “new” or “revisionist” images of the higher education experience being developed for gendered discourse in specific Asian contexts?

References

Asia Development Bank (ADB). 2011. Higher Education Across Asia: An Overview of Issues and Strategies. Mandaluyong City, Philippines.

Association of American Colleges and Universities. 2014. Peer Review. Special Issue, Gender Issues in STEM. https://www.aacu.org/peerreview/2014/spring. Accessed July 3, 2016.

Bagilhole, B., and K. White. 2011. Gender, Power and Management: A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Higher Education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bagilhole, B., and K. White. 2013. Generation and Gender in Academia. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

LeeAn, J. 2009. “Civil Society: New Feminist Network for ‘Glocal’ Activism”. Inter Press Service, April 20. http://www.ipsnews.net/2009/04/civil-society-new-feminist-network-for-39glocal39-activism/.

Li, Xiaojiang. 1995. “The Development and Prospect of Women’s Studies in Mainland China.” In Gender and Women Studies in Chinese Societies (in Chinese), edited by M.C. Cheung, H.M. Yip, and K.P. Lan, 1–20. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press.

Lievrouw, Leah. 2011. Alternative and Activist New Media. Malden, MA: Polity.

Ma, Wanhua. 2010. Equity and Access to Tertiary Education. World Bank. Available at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EDUCATION/Resources/278200-1099079877269/547664-1099079956815/547670-1276537814548/China_Equity_Study.pdf.

Morley, L. 2013. Women and Higher Education Leadership: Absences and Aspirations. London, UK: The Leadership Foundation for Higher Education.

Ng, Soo Boon Ng. 2016. Sharing Malaysian Experience in Participation of Girls in Stem Education. UNESCO, International Bureau of Education. Available at: http://www.ibe.unesco.org/sites/default/files/resources/ipr3-boon-ng-stemgirlmalaysia_eng.pdf.

UNESCO. 1993. Women in Higher Education Management. Paris: UNESCO, London: Commonwealth Secretariat.

UNESCO. 2010. Gender Issues in Higher Education. Bangkok: UNESCO.

UNESCO. 2015. “A Complex Formula: Girls and Women in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics in Asia.” UNESCO and Korean Women’s Development Institute. Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002315/231519e.pdf.

Zhu, Ping. 2014. “The Phantasm of the Feminine: Gender, Race and Nationalist Agency in Early Twentieth-Century China.” Gender & History 26 (1), 147–166.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Cuthbert, D., Lee, M.N.N., Deng, W., Neubauer, D.E. (2019). Framing Gender Issues in Asia-Pacific Higher Education. In: Neubauer, D.E., Kaur, S. (eds) Gender and the Changing Face of Higher Education in Asia Pacific. International and Development Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02795-7_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02795-7_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-02794-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-02795-7

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)