Abstract

Cervical cytology screening of women has quite successfully led to secondary prevention of cervical cancer, primarily due to identification and treatment of cervical cancer precursors (IARC. Handbooks of cancer prevention, Cervix cancer screening, vol. 10. IARC Press, Lyon, 2005). Recently, much interest has been generated to improve the efficiency of cervical cancer screening initiatives. One can presume with rising healthcare costs, liquid-based cytology availability, and a growing population, current costs are high. Another reason to change screening programs was the realization that over-screening was potentially causing psychological and physical harm.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) studies have demonstrated that virtually all cases of cervical cancer and its’ precursor lesions are associated with potentially carcinogenic genotypes of HPV. We also now know that the vast majority of sexually active people have been exposed to HPV. Studies have shown that in most cases of healthy women, the HPV infection is transient, and benign and clears within 8–24 months. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Cancer Society, the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and the American Society for Clinical Pathology have developed updated recommendations for screening for cervical cancer.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Part I. Cervical Cancer Screening

Introduction

Cervical cytology screening of women has quite successfully led to secondary prevention of cervical cancer, primarily due to identification and treatment of cervical cancer precursors [1]. Many of us may therefore question why screening guidelines need to change. Paramount to the premise of mass screening programs, screening tests should be accurate and economical. Cytology-based cervical cancer tests have demonstrated poor reproducibility and poor sensitivity to identify precancerous lesions and are thought to be overutilized in low-risk populations [2,3,4]. Therefore, much interest has been generated to improve the efficiency of cervical cancer screening initiatives. One estimate of the annual cost of Pap test screening programs in women in the United States in 1992 was 6 billion dollars [5]. One can presume with rising healthcare costs, liquid-based cytology availability, and a growing population, current costs are significantly higher. Another reason to change screening programs was the realization that over-screening was potentially causing psychological and physical harm.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) studies have demonstrated that virtually all cases of cervical cancer and its precursor lesions are associated with potentially carcinogenic genotypes of HPV [6, 7]. We also now know that the vast majority of sexually active people have been exposed to HPV. Studies have shown that in most cases of healthy women, the HPV infection is transient and benign and clears within 8–24 months. Most HPV-infected women will not develop cervical cancer or even its precursors [8,9,10,11]. It is the unresolved or persistent HPV infections with carcinogenic high-risk (HR) HPV strains, in select individuals, that lead to the development of cervical cancer and its precursors [8, 12]. Studies demonstrate that the average time it takes for high-grade cervical neoplasias to progress to invasive cancer is 10 years [11]. The need to better identify who these at risk women are and provide them closer screening intervals is essential when guidelines are developed. We know that HIV-infected women are at greater risk of cervical neoplasia with high-risk HPV (HR HPV) infection and that cigarette smoking may be a cofactor for progression or persistence of HR HPV infection and cervical neoplasia [13].

The development and incorporation of testing for HR HPV, offered by liquid-based cytology specimens, have improved the efficiency and sensitivity of cervical cancer screening programs [10, 12]. In the United States, HR HPV testing has proven to be cost-effective and has improved the sensitivity for detecting cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in women with equivocal testing, such as ASCUS (atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance ). HR HPV testing has also been demonstrated to be valuable for primary screening of women aged 30 and older. This is due to the fact that there is greater reproducibility of testing for the presence of HR HPV over cervical cytology. In fact, in 2014 the FDA approved the Roche Cobas test for HR HPV as an option for primary cervical cancer screening programs in women 25 and older. This assay detects the presence of 14 high risk HPV types. It specifically detects types 16 and 18 and pools the other 12 HR HPV types [14, 15] (Table 10.1). An alternate and more widely utilized screening option exists that is the method supported by the American Cancer Society, the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and the American Society for Clinical Pathology. In the most recent Practice Bulletin Number 157, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recognizes both screening methods [15]. The current recommendations recognize the information that the typical progression of the incident HR HPV infection to precancer of the cervix occurs over 2–10 years and from precancer to invasive cancer over greater than or equal to 10–15 years [10, 11]. The extremely low risk of cervical cancer and the fact that most dysplasias in adolescents under 21 years of age regress spontaneously have led to the recommendation that the timing of first Pap is to be at age 21. Furthermore, it is not recommended to screen women under 30 years old for HR HPV. Age 30 has been chosen in the United States because at this age, women are past the peak of self-limited transient infections, and the positive predictive value (PPV) of presence of HR HPV for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancers is greater than in the younger population [12]. It is important to note that these screening guidelines do not apply to women that are HIV infected, are immunocompromised, and have a history of diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure or history of prior cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or cervical cancer. The age of onset of coitus is no longer a criterion that determines the need to begin Pap screenings [15]. It is also important to note that these guidelines are for screening of healthy individuals and do not apply to women with visible lesions on their cervix, post coital bleeding, or other factors associated with cervical pathology.

ACOG released new evidence-based guidelines in December 2009 and updated these in January 2016 recommending that Pap testing (cytology) begin at age 21 and be repeated every 3 years between ages 21 and 29. They did not recommend liquid-based cytology over conventional monolayer glass slides. They further stated that women over 30, whom are low risk, may have cytology-alone screening every 3 years. Preferentially, however, they recommended co-testing consisting of cytology and HR HPV testing every 5 years in low-risk women between 30 and 65. The following exclusions to this were stated: women with a history of CIN 2 or greater require cytology screens for at least 20 years after treatment and women infected with HIV present special risk, women who are immunocompromised (specifically addressed were patients that have received organ transplants), and women who had in utero DES exposure. Women whom have had a hysterectomy and have a history of CIN 2 or greater or women whom a negative history cannot be documented should continue to have Paps [13, 15]. ACOG guidelines state that “when a woman’s past cervical cytology and surgical history are not available to the physician, screening recommendations may need to be modified” [13]. See Tables 10.2 and 10.3.

Controversies About Screening Intervals

Tremendous success has been achieved in decreasing cervical cancer rates in the United States. Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) cancer data reports an incidence of 6.5/100,000 new cases of cervical cancer in US women in 2006. The same incidence in 1975 was 14.8/100,000. This represents over a 50% decline [13, 18]. As we have learned more about the biology of cervical cancer, and its requisite association with approximately 15 known HR HPV strains , we have been able to develop more accurate and efficient guidelines for detection of cervical cancer and its precursors. Evidence-based studies have demonstrated that in low-risk, well-selected women, screening intervals can be safely lengthened [18,19,20]. However, several recent surveys have demonstrated that the healthcare providers are reluctant to adopt the new lengthened screening intervals. An excellent editorial exists entitled, “Identifying a ‘Range of Reasonable Options’ for Cervical Cancer Screening.” The authors discuss the balance between too frequent screening potentially resulting in overidentification of a transient self-limited infection and maximizing early detection and treatment of significant precursors to cervical cancer [21]. A study published by Kinney et al. shared their belief that if women and their providers were given the choice of cytology and co-testing at 5-year intervals with its estimated lifetime detection rate of cervical cancer at 0.74% as compared to co-testing every 3 years of detection rate being 0.47%, most would choose the latter interval for cervical cancer screens [22]. As healthcare providers, our patients look to us for guidance in decision-making regarding their health and wellness. We are encouraged to practice evidence-based medicine . Health insurance companies have become increasingly involved in determining what tests and medical care they believe are “medically necessary” and may elect not to authorize or pay for select care and testing.

As educated and experienced providers of healthcare, we need to understand and support the care that we provide. Performing cytology testing in adolescents, in women under age 21 years old, was a means in identifying transient HPV infections and sometimes their associated cervical neoplastic changes, the majority of which clear within 1–2 years. This led to emotional difficulties, anxiety, financial concerns, and excisional procedures for dysplasia [15]. Excisional procedures for cervical dysplasia in adolescents have felt to lead to an increase in preterm births and have raised concerns regarding cervical insufficiency [23]. The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) in 2006 encouraged a conservative approach in adolescents with histology findings of less than CIN 3. ACOG endorsed these recommendations and also released new practice guidelines in 2009, moving the baseline cervical cytology exam to age 21 years. This is without regard to age of first sexual intercourse and does not negate the need for annual gynecologic exams and STI testing in sexually active adolescents [24,25,26]. The incidence of cervical cancer in adolescents is extremely low. 0.1% of cases of cervical cancer occur before age 21. The US Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data from 2002 to 2006 and the US national data from the CDC estimate an incidence rate of 1–2 cases per 1,000,000 girls aged 15–19 years old. This amounts to 14 cases on the average per year from 1998 to 2003 in that age group [14, 18]. If the new guidelines had been applied to begin cervical cytology at 21 years of age, these young women may have been diagnosed at an even more advanced stage. It is also possible that they had risk factors such as DES exposure and HIV infection or were otherwise immunocompromised. I believe this sort of data makes the healthcare provider concerned that they will miss the opportunity to identify early cervical cancers and high-grade lesions.

Despite the widespread knowledge of the new screening guidelines, healthcare providers have been slow to adopt these recommendations. Several factors may be influencing this practice. Studies have demonstrated that patients are often incorrect in remembering the timing and results of their last Pap test. Specifically, they underestimated the length of time and incorrectly reported abnormal results as normal [27, 28]. Additionally, providers need to educate women that lengthening the interval between Pap smears does not apply to all women and that annual gynecologic exams are still appropriate. Another factor that may influence healthcare providers’ decision to not follow the new screening interval recommendations is their own awareness that these evidence-based guidelines also examined the cost-effectiveness and efficiency of screening programs, as described in published studies [29]. Also, the ability to identify the low-risk patient correctly may be difficult. A patient may state that she is monogamous, while in fact she is not. The patient’s partner may not be monogamous. The patient or her partner may participate in high-risk sexual behavior, unknown to the provider. In a typical practice, very few healthy “low-risk” patients have HIV testing. Patients may be unaware of being infected with the HIV virus. Furthermore, documentation of prior Paps is often lacking as patients move and change clinics and healthcare providers. Providers cannot always trust the quality of the reading and the collection or even be 100% certain that the Paps were not mixed up in a busy clinic or office setting. It is also possible that the laboratories might mix up patients’ specimens. Perhaps of most importance, if we perform screens every 5 years and the last result was in error, the true screening interval becomes 10 years. This is enough time for a cervical cancer to develop.

Many of us have developed what we refer to as “experience-based guidelines .” In my practice I have implemented every 3 year co-testing for low-risk women aged 30 and over. I simply believe that extending the interval to every 5 years adds risk (Table 10.4). I believe we do need to stay open-minded to the new findings and recommendations. We need to realize that performing Paps on low-risk adolescents was causing more harm than being helpful. We need to develop strategies that work for us and our patients in carefully choosing who needs more frequent screens and who does not.

Part II. Management of Abnormal Pap Results

Advances in diagnosis and treatment of precursors to cervical cancer have greatly reduced the incidence of invasive cervical cancer in the United States [1]. In the past, after diagnosis of an abnormal Pap smear, women underwent random four quadrant biopsies, cervical conizations, and hysterectomies for cervical cancer precursors. In the 1970s, colposcopy was introduced, and these aggressive diagnostic and treatment choices for cervical neoplasias become less frequent. The more conservative ablative treatments of the lesions become favored and proved to be effective. Ablative methods include laser, cryotherapy, and electrocautery. Acetic acid has also been used on the cervix. In the 1990s, healthcare providers began to utilize the office-based excisional procedure, the loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP). The LEEP became popular because it provided a pathologic specimen that could be examined to exclude the presence of a more advanced lesion that might be unrecognized in an ablation procedure. However, as our knowledge of the high regression rate of the cervical neoplasias grew, researchers and clinicians became concerned that we were harming women by performing unnecessary excisions on lesions that would quite often resolve on their own. These excisional procedures are associated with bleeding, scarring, and the inherent risks associated with vaginal procedures [23]. Additionally, some studies began to associate LEEPS and cervical conizations with preterm deliveries [29, 30]. The last decade has begun an ongoing investigation and series of consensus guidelines on the safest and best management for detecting, treating, and preventing cervical cancer and its precursors.

A consensus conference was held in March of 2012 entitled the LAST (Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology) Project. The ASCCP , the College of American Pathologists, and 35 other organizations developed an updated terminology for histopathology of HPV-associated squamous lesions associated with the anogenital tract. This new terminology has simplified the nomenclature between cytology and histology. Cervical cytology, in accordance with the Bethesda system, utilizes the terms low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) (see Table 10.5). Cervical histopathology utilizes the three-tiered CIN (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia) terminology. Both CIN 2 and CIN 3 are considered high-grade lesions. The category of CIN 2 was found to be somewhat subjective upon review by experts. The LAST Project work group recommended adding p16 immunostaining to confirm the diagnosis of CIN 2. Positive p16 staining correlates well with the diagnosis of HSIL. They also recommended developing a two-tiered nomenclature system for histopathology. Previously named CIN 1 and p16-negative CIN 2 are now called LSIL. P16-positive CIN 2 and CIN 3 histopathology specimens are now called HSIL [32]. See Table 10.6.

Management based upon the diagnosis of high-grade or low-grade histology of the cervix correlates well with the LAST Project two-tiered nomenclature. Positive HR HPV tests in women over 30 more likely represent persistent infection and are more likely to have had the opportunity to cause neoplasia. In younger women, HR HPV infection is more likely to represent the transient self-limited infection. As previously discussed, there is some concern that cervical procedures, especially the excisional methods, may lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes. If one keeps these facts in mind, the treatment of abnormal cervical lesions may be simplified. Low-grade intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) should be managed by observation. With some important exceptions, high-grade intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) should be ablated or excised. Excisional procedures are typically offered for women over 40 as results from cohort studies have shown higher failure rates with cryoablation in this age group [33]. This age group is also more often done with childbearing. When we encounter HSIL lesions in adolescents and young women who have future childbearing concerns, conservative observation with semiannual colposcopy and cytology is acceptable. It is important to note that treatment is indicated, in this young group, if the lesion is large and enlarging or the entire transformation zone (inadequate colposcopy) cannot be seen. If the HSIL persists for 2 years, treatment is recommended [32].

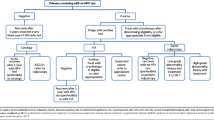

The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) has developed extensive algorithms and a mobile “app” available for purchase at their website www.asccp.org/APP. Management guidelines can be customized for your patient by her age, pregnancy status, HR HPV, and prior testing results. These algorithms are copyright protected for publication but are available on their website.

Abbreviations

- ACOG:

-

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- ASCCP:

-

American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology

- ASCUS:

-

Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance

- CIN:

-

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

- HR HPV:

-

High-risk human papilloma virus

- HSIL:

-

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- LAST:

-

Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology

- LEEP:

-

Loop electrosurgical excision procedure

- LSIL:

-

Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

References

IARC. Handbooks of cancer prevention, Cervix cancer screening, vol. 10. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005.

Nanda K, McCrory DC, Myers ER, et al. Accuracy of the Papanicolaou test in screening for and follow-up of cervical cytologic abnormalities: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:810–9.

Cuzick J, Clavel C, Perry KU, et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1095–101.

Stoler MH, Schiffman M. Interobserver reproducibility of cervical cytologic and histologic interpretations: realistic estimates from the ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study. JAMA. 2001;285:1500–5.

Kurman RJ, Henson DE, Herbst AL, et al. Interim guidelines for management of abnormal cervical cytology. The 1992 National Cancer Institute Workshop. JAMA. 1994;271:1866–9.

Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189:12–9.

Schiffman MH, Bauer HM, Hoover RN, et al. Epidemiologic evidence showing that human papillomavirus infection causes most cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:958–64.

Wright TC Jr, Schiffman M. Adding a test for human papillomavirus DNA to cervical-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:489–90.

Mosiccki AB, Schiffman M, Kjaer S, Villa LL. Updating the natural history of HPV and anogenital cancer. Vaccine. 2006;24(suppl 3):S3/42–51.

Castle PE. The potential utility of HPV genotyping in screening and clinical management. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2008;6(1):83–95.

Baseman JG, Koutsky LA. The epidemiology of human papillomavirus infections. J Clin Virol. 2005;329(suppl (1)):S16–24.

Wright TC Jr, Schiffman M, Solomon D, et al. Interim guidance for the use of human papillomavirus DNA testing as an adjunct to cervical cytology for screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:304–9.

Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no 109: cervical cytology screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1409–20.

Silver MI, Rositch AF, Burke AE, Chang K, Viscidi R, Gravitt PE. Patient concerns about human papillomavirus testing and 5-year intervals in routine cervical cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:317–29.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Cervical cancer screening and prevention. Practice bulletin no. 157. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:e1–20.

WK H, Ault KA, Chlemow D, Davey DD, Goulart RA, Garcia FA, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidelines. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:330–7.

Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, Killackey M, Kulasingam SL, Cain J, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. ACS-ASCCP-ASCP Cervical Cancer Guideline Committee. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:147–72.

Ries LA, Melbert D, Krapcho M, Stinchcomb DG, Howlader N, Horner MJ, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2006. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 2009.

Arbyn M, Bergeron C, Klinkhamer P, Martin-Hirsch P, Siebers AG, Bulten J. Liquid, compared with conventional cervical cytology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:167–77.

Ronco G, Cuzick J, Pierotti P, Cariaggi MP, Dalla Palma P, Naldoni C, et al. Accuracy of liquid based versus conventional cytology: overall results of new technology for cervical cancer screening: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335:28.

Sawaya GF, Kuppermann M. Identifying a “range of reasonable options” for cervical cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:308–9.

Kinney W, Wright TC, Dinkelspiel HE, DeFrancesco M, Cox JT, Huh W. Increased cervical cancer risk associated with screening at longer intervals. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:311–5.

Khan MJ, Smith-McCune K. Treatment of cervical precancers. Back to basics. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1339–42.

Kyrgiou M, Koliopoulos G, Martin-Hirsch P, Arbyn M, Prendiville W, Paraskevaidis E. Obstetric outcomes after conservative treatment for intraepithelial or early invasive cervical lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;367:489–98.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Evaluation and management of abnormal cervical cytology and histology in adolescents. ACOG Committee opinion no. 436. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1422–5.

Wright TC Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ, Solomon D. 2006 guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. 2006 American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology-sponsored Consensus Conference. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:346–55.

Mamoon H, Taylor R, Morrell S, Wain G, Moore H. Cervical screening: population-based comparisons between self-reported survey and registry-derived Pap test rates. Aus NZ J Publ Health. 2001;25:505–10.

Sawyer JA, Earp JA, Fletcher RH, Daye FF, Wynn TM. Accuracy of women’s self-report of their last pap smear. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:1036–7.

Bevis KS, Biggio JR. Cervical conization and the risk of preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):19–27.

Arbyn M, Kyrgiou M, Simoens C, et al. Perinatal mortality and other severe adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a1284.

Nayar R, Wilbur DS, editors. The Bethesda system for reporting cervical cytology: definitions, criteria, and explanatory notes. 3rd ed. New York: Springer; 2015.

Waxman AG, Chelmow D, Darragh TM, et al. Revised terminology for cervical histopathology and its implications for management of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions of the cervix. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1465–71.

Melnikow J, McGahan C, Sawaya GF, Ehlen T, Coldman A. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia outcomes after treatment: long-term follow-up from the British Columbia Cohort Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:721–8. 22. ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) G.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Johnson, J.L. (2018). Screening for Cervical Cancer and Management of Its Precursor Lesions. In: Knaus, J., Jachtorowycz, M., Adajar, A., Tam, T. (eds) Ambulatory Gynecology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7641-6_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7641-6_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4939-7639-3

Online ISBN: 978-1-4939-7641-6

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)