Abstract

Patients with cancer are at a high risk of developing acute kidney injury (AKI). Notwithstanding the considerable advances in cancer care over the past decade, the incidence of AKI among patients with cancer remains high. This high incidence of AKI is multifactorial with many contributory factors including cancer-related and patient-specific factors as well as chemotherapy-related renal toxicity. Patients are aggressively treated even at an older age with the complicating predispositions to AKI that are associated with aging. Furthermore, the success of cancer treatment has transformed it from a short-term to an increasingly chronic therapeutic regimen. Chronic treatments bring out renal toxicities of both the underlying disease as well as its treatments not readily apparent with short-term treatment. In turn, AKI can negatively impact the outcome of management of cancer patients by limiting the dosage of chemotherapy, reducing the likelihood of achieving complete remission, increasing frequency and length of hospitalization, increasing cost of care, and risk of CKD, ESKD, and mortality. Therefore, prevention and timely management of AKI should be a central focus of oncologists, nephrologists, other subspecialists and primary care physicians who provide care to cancer patients. In this chapter we review the current knowledge of AKI in cancer patients, focusing on epidemiology, etiology, and its consequences.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

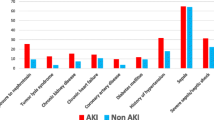

There are over 13 million patients who live with or had a history of cancer in 2010 in the USA [1]. While the overall incidence of AKI among this vulnerable group remains unknown, data from several sources suggest that it is quite high and its impact on morbidity, mortality, and cost of care is quite substantial. A Danish population-based study of 1.2 million cancer patients showed 1 and 5 year risk for AKI of 18 and 27 %, respectively [2]. On the other hand, analysis of recent data from 3558 patients admitted over a 3-month period to the comprehensive cancer center at University of Texas M.D. Anderson, Houston, Texas reported an AKI rate of 12 % in which 45 %, arguably preventable, occurred during the first 2 days of admission [3]. Studies conducted in cancer patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) by the same group showed that patients with AKI were more likely to have diminished 60 day survival, as low as 14 % (OR 14.3), and increased associated hospitalization cost by as much as 21 % [4].

Cancer is associated with many risk factors for AKI. Patients with cancer can be debilitated and may be predisposed to hemodynamic compromise associated with total or effective volume compromise. The underlying cancer itself can involve the kidney, and hence, predispose or directly cause kidney injury. Many chemotherapeutic agents can cause AKI. Additionally, AKI impacts the dosing of some chemotherapeutic agents, necessitating adjustment for diminished renal clearance. Patients with cancer who develop AKI are more likely to receive suboptimal dosing of chemotherapy [5]. Therefore, with the emergence of potent and more aggressive chemotherapeutic protocols, many of which are now accessible to previously excluded elderly patients with cancer, medical management of kidney health in cancer patients has become more complicated, and necessarily, more multidisciplinary.

This chapter reviews the epidemiology of AKI in cancer patients. The challenging issues about timely diagnosis and management are also discussed. Topics such as tumor lysis syndrome, hyponatremia, and other electrolyte abnormalities that complicate certain malignancies are discussed in detail in other chapters, and hence, are only briefly described in this chapter.

Epidemiology

How common is AKI among cancer patients? The answer depends on the subpopulation of cancer patients of interest, as well as the clinical setting, for example, intensive care unit versus general inpatient service . Also, because the incidence of AKI is dependent on how AKI is defined, comparisons are most reliable if they belong to studies that defined AKI uniformly based on RIFLE (risk, injury, failure, loss, end-stage renal disease), AKIN (acute kidney injury network), or KDIGO criteria [6–8]. RIFLE criteria define 3 levels of AKI based on the percent increase in serum creatinine from baseline: risk (≥ 50 %), injury (≥ 100 %), and failure (≥ 200 % or requiring dialysis) [9]. Until 3 years ago, when studies of AKI in cancer started adopting RIFLE criteria to define AKI, over 35 different definitions of AKI were used in studies [3], precluding a reliable comparison of findings among studies.

In a Danish population-based study cited earlier [2], the 1-year and 5-year incidence of AKI in the overall cancer population was 17.5 and 27 %, respectively. Cancers of the kidney, gall bladder/biliary tract, liver, bone marrow (multiple myeloma), pancreas, and leukemia confer the highest risk with 1-year risk of AKI of 44, 34, 33, 32, 30, and 28 %, respectively .

In 3558 hospitalized cancer patients, 12 % of patients developed AKI. Notably, 45 % of incident AKI occurred during the first 2 days of admission [3]. On comparison, the published incidence of AKI among patients without cancer is lower (5–8 %) [10, 11]. When the same investigators examined a select cohort of 2398 critically ill cancer patients in the medical and surgical ICU with administration of serum creatinine < 1.5 mg/dL, they reported an overall incidence of AKI to be 12.6 % [4]. This incidence is lower than the historically reported incidence of 13–42 % [12–14]. When the analysis was limited to cancer patients admitted to the medical ICU only, the incidence of AKI was 21 %. The relatively lower overall incidence of AKI in this study was multifactorial: cancer patients with significant baseline CKD were excluded, and the study included a large proportion (58 %) of patients admitted to the surgical service (many electively), who might be expected to have a lower risk of AKI as they are not as acutely ill as patients admitted to medical ICUs .

In the study mentioned above, the cancers associated with the highest incidence of AKI in the ICU setting were hematologic malignancies such as leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma, with combined AKI incidence of 28 % [4]. This incidence was notably lower than that reported by another recent prospective study that measured the incidence of AKI (defined by RIFLE criteria) among ICU patients with newly diagnosed high-grade hematological malignancies (non-Hodgkin lymphoma, acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and Hodgkin disease) who did not show preexisting CKD. The incidence of AKI in this study was 68.9 % [5].

Not surprisingly, among patients with hematologic malignancies, those treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) have the highest risk of AKI, with the risk varying with the type of HSCT. Myoablative allogenic HSCT is associated with a higher risk of AKI (> 50 %) [15–19] than nonmyoablative allogenic HSCT (29–40.4 %) [18–20], presumably because the former involves use of a more toxic conditioning regimen. Also, because autologous HSCT is not complicated by graft versus host disease (GVHD), and does not require use of calcineurin inhibitors, it is associated with a relatively lower incidence of AKI (22 %) compared to allogenic HSCT [21] .

Four main points may be deduced from these studies: (1) the incidence of AKI among hospitalized cancer patients is higher than that of patients without cancer; (2) acutely ill cancer patients admitted to the ICU have yet higher risk of AKI; (3) some cancers are associated with higher risk of AKI than others; and (4) treatment with HSCT, especially myeloablative allogenic HSCT, further raises the risk of AKI associated with malignancies .

Causes of AKI in the Patient with Cancer

The etiologic framework of AKI in the patient with cancer is similar to that of noncancer patient in which causes of AKI can be categorized based on the location of the culpable “lesion” as prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal causes (Fig. 1.1). As with AKI in noncancer patients, this approach lends itself to easy application. Although this is a useful construct, certain etiologies of AKI may not neatly fall exclusively into one of the three categories. For instance, some etiologies, such as nephrotoxicity associated with calcineurin inhibitors can be due to both prerenal and intrinsic renal effects due to their effects on vasoconstriction of prerenal and intrarenal vasculature as well as their direct epithelial cell toxicity. Yet, other causes of AKI, such as intravascular hypovolemia may initially lead to prerenal AKI. If the renal ischemia persists, however, it may ultimately lead to tubular injury and necrosis, which moves the etiology into the “intrinsic renal” category. Furthermore the etiology of AKI in cancer patients is often multifactorial .

Prerenal Causes

Sepsis and hypoperfusion are commonly reported causal etiologies of AKI in patients with cancer [22, 23] . Sepsis is an example, however, of a combination of prerenal and intrinsic renal AKI, since sepsis has multiple effects on the tubular epithelial cell as well as the endothelial cell. Sepsis is a common cause of hypovolemia via capillary leak, especially among ICU cancer patients. Cancer patients are prone to developing cancer or chemotherapy related conditions that ultimately result in renal hypoperfusion. In a recent study of patients with hematologic malignancies, AKI was caused by renal hypoperfusion in 48.2 % of cases [5]. True intravascular volume depletion often results from diarrhea, vomiting, decreased oral intake, and overdiuresis. Additionally, effective circulating volume declines in the setting of malignant ascites and pleural effusions. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAID) and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) impair the renal vascular autoregulatory systems, thereby acting synergistically with hypovolemia to create a renal hypoperfused state .

Hypercalcemia, which occurs in 20–30 % of cancer patients over the course of their illness [24], causes vasoconstriction and the associated augmented natriuresis leads to volume depletion. Renal vein thrombosis and impaired cardiac function, for example, due to pericardial effusion, also can contribute to renal hypoperfusion. Likewise, hepatic sinusoidal obstructive syndrome (HSOS), also known as hepatic veno-occlusive disease (VOD), results in “hepatorenal-like” physiology, with impaired renal perfusion.

Case #1

A 56-year-old male with renal cell carcinoma receives an mTOR inhibitor for metastatic disease. Over 2 weeks, a rapid rise in serum creatinine is noted. Urinalysis reveals no red blood cells, white blood cells, or blood. Complete blood count shows a slight decrease in platelet count and no eosinophilia. Granular casts are noted on examination of his urinary sediment. What is the most likely finding in the kidney biopsy?

-

a.

Thrombotic microangiopathy

-

b.

ATN

-

c.

Acute interstitial nephritis

-

d.

FSGS

Intrinsic Renal Causes

Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) is a common, nonspecific endpoint of renal tubular injury. Persistent ischemia from any etiology, and nephrotoxins, including cytotoxic chemotherapy and nephrotoxins released during tumor lysis, result in acute tubular injury . The list of nephrotoxic agents that cause toxic ATN is long. The most common chemotherapeutic agents that have been associated with ATN are presented in Table 1.1. In addition, an entire chapter in this book is dedicated to chemotherapy agents and kidney disease for further details. This list continues to expand to include some ever emerging new chemotherapeutic agents such as inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) [25]. It is also important to recognize that there can be significant ischemia to the kidney even though total renal blood flow is preserved if the distribution of renal blood flow leaves important regions of the kidney, such as subsections of the outer medulla, underperfused [26].

It is important to recognize that ATN is a diagnosis, which depends upon evidence that there is necrosis of epithelial cells. ATN is not a clinical diagnosis. The diagnosis can be made noninvasively, however, by observing clear evidence for tubular cell necrosis in the urine sediment. The clinical entity associated with ATN is AKI. The diagnosis of ATN is based on the presence of “muddy brown” or granular casts on urine microscopy. Biopsy is not routinely performed to diagnose ATN, but characteristic findings on renal biopsy include tubular cell degeneration, loss of brush border, apoptosis, and evidence for a reparative response by the tubule, for example, mitotic figures. Immunohistochemical staining shows notable increase in cell cycleengaged cells and derangement of tubular Na+, K+-ATPase expression. There are no radiographic modalities for specifically diagnosing ATN in the clinical setting. As the current diagnostic methods rely on late markers of ATN, diagnosis, and, in turn, treatment of ATN is often delayed. There are ongoing efforts to optimize the use of biomarkers that could diagnose ATN noninvasively, sensitively, and early in the disease process [27–29]

Case #1 Follow-Up and Discussion

The patient presented previously, shows ATN in the presence of a urine sediment with granular muddy brown casts. As noted above mTOR inhibitors have been reported to cause ATN as well as proteinuric renal diseases.

It is not always the case that the correction of renal ischemia, resolution of septic shock or removal of an offending nephrotoxin, leads to complete resolution of ATN. The initial insult may result in a repair process that is incomplete and maladaptive. This may not be initially apparent, but is supported by the higher risk of future CKD [30–32]. Therefore, prevention of ATN should be the goal. Prophylaxis against ATN is aimed at hemodynamic optimization, intravascular volume expansion with crystalloids or diuresis, to augment cardiac filling and renal perfusion and reduce intrarenal concentrations of nephrotoxic agents. The approach also involves avoiding sepsis and treating the cancer before it has an impact on renal function either directly or indirectly. Once AKI is established, treatment is aimed at optimizing hemodynamic support, treating sepsis if it is present and withdrawing or reducing the dose of the nephrotoxic agent if possible .

Lymphomatous Kidney Infiltration (LIK)

Lymphomatous kidney infiltration is common, albeit underdiagnosed, among cancer patients . Its incidence ranges from 6 to 60 % in autopsy series [33]. In the largest autopsy case series comprising 696 cases of malignant lymphoma, LIK was found in 34 % of cases, although only 14 % were diagnosed before death. Although kidney infiltration was bilateral in the majority (74 %) of cases, it was associated with acute renal failure only in 0.5 % of cases [34].It must be considered however that the definition used for acute renal failure in 1962, when this paper was published, is very different from the one used today for AKI. This supports the observation that LIK is a common complication of hematologic malignancies, but may not be a common cause of severe AKI in these patients.

The reason for LIK underdiagnosis is multifactorial. Most patients with LIK have no clinical renal manifestations [33], and when present, clinical manifestations such as flank pain, hematuria, abdominal pain, palpable mass, hypertension, and subnephrotic range proteinuria—are not specific to LIK [33, 34]. While lymphoma cells may be present on urinalysis they frequently go unnoticed. Common findings on urinalysis are mild proteinuria, few red blood cells, white blood cells, and granular casts. The sensitivity of radiographic diagnosis is also poor with diagnosis of LIK by computed tomography imaging in the range 2.7–6 % [35]. While LIK is almost always diagnosed by renal biopsy [36], a biopsy is not frequently obtained because cancer patients with suspected LIK often have nonrenal cancer complications to which their renal insufficiency may be ascribed. Concurrent coagulopathy in the acutely ill cancer patient is often seen as a relative contraindication to renal biopsy. A kidney biopsy is pursued when the diagnosis of LIK would prompt initiation or modification of chemotherapeutic agents.

The mechanism of LIK-induced AKI is not completely established. Since tubules and glomeruli usually appear morphologically normal on biopsy, it has been proposed that interstitial and intraglomerular pressure elevation due to lymphocytic infiltrations of these compartments is the underlying mechanism of the AKI [33, 36]. Proponents of this mechanism also point to improved renal function with chemotherapy being supportive of this hypothesis. Complete renal recovery to baseline function is not frequent [37]. Management of LIK is focused on treatment of the underlying malignancy .

Myeloma Cast Nephropathy

Renal impairment affects 20–40 % of newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma (MM) [38, 39]. Some case series report that up to 10 % of patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma have AKI severe enough to warrant dialysis [39, 40]. While cast nephropathy is not the sole etiology of AKI in patients with multiple myeloma, cast nephropathy is the most common finding on renal biopsy, found in 41 % patients biopsied with monoclonal gammopathies [41]. In this cohort, AL-amyloidosis was found in 30 %, light chain deposit disease in 19 %, tubulointerstitial nephritis in 10 %, and cryoglobulinemic kidney lesions with MM in 1 patient. Factors that promote cast formation and AKI in myeloma include dehydration, delivery of high burden of serum-free light chains to the distal nephron, acidic urine, concurrent use of furosemide or NSAIDs, hypercalcemia, and intravenous contrast use [42, 43].

The majority of studies show that AKI in patients with MM is associated with increased morbidity and mortality [44–46]. By contrast, in one case series, when adjusted for the stage of MM, renal failure had no impact on survival [47]. It was suggested that, as renal function is closely correlated with myeloma cell mass [48], the correlation between renal impairment and increased mortality may be more reflective of the burden of MM than that of renal impairment per se [49]. It is noteworthy that in other malignancies, as in noncancer patients, AKI correlates with increased morbidity and mortality. It will be surprising if this is not the case in MM as well. Treatment of renal disease associated with myeloma is discussed elsewhere in this book .

Case #2

A 56-year-old male is noted to have subacute rise in serum creatinine and development of hematuria and proteinuria. Serological workup is negative but serum-free light chains revealed an abnormal ratio of elevated kappa to lambda of 9 (serum creatinine is 1.5 mg/dl). A bone marrow study revealed MGUS (monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance) with only 4 % IgG kappa plasma cells. A kidney biopsy revealed a MPGN pattern of injury with immunofluorescence positive for IgG kappa. How do you proceed with treatment?

-

a.

Start steroids for treatment of MPGN

-

b.

Treat underyling B cell clone in the bone marrow and treat this as monoclonal gammmopathy of renal significance

-

c.

Repeat the bone marrow

-

d.

No treatment till plasma cells are > 10 % and a diagnosis of myeloma is made.

Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis Secondary to Monoclonal Gammopathies

The spectrum of renal injury associated with monoclonal gammopathy is broad [50]. While, as stated above, the majority of kidney diseases associated with monoclonal gammopathies are due to the deposition of light chains [51], it is becoming increasingly recognized that an immune complex glomerulonephritis can occur. This is characterized by subendothelial and mesangial immune complex deposition and is an underappreciated cause of kidney injury caused by monoclonal gammopathies both in native kidneys [52] as well as in renal allografts [53] .

Case #2 Follow Up and Discussion

In a large biopsy case series, the incidence of monoclonal gammopathyassociated MPGN was higher than hepatitis-associated MPGN and was nearly equivalent to the incidence of myeloma kidney [52]. This study highlights the important point that MPGN is associated with a wide spectrum of plasma cell and lymphoproliferative disorders, ranging from multiple myeloma at one extreme and MGUS (monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance) at the other end of the spectrum. Because many patients with MPGN have underlying monoclonal gammopathy, there is a need for careful investigation before using the diagnostic label of MGUS—because what may appear as “undetermined significance” may be causally associated with MPGN. Similarly, before diagnosing idiopathic MPGN, a full work-up for gammopathies—including serum electrophoresis—should be undertaken. Patients with monoclonal gammopathy have an incidence of MPGN recurrence that is twice of that seen in patients without monoclonal gammopathy (66.7 vs. 30 %) [54]. Because kidney biopsies are generally delayed—especially, when anti-GBM or pauci immune diseases are not the suspected etiology of AKI, it is unknown how frequently AKI is the initial presentation of MPGN. It is likely, however, that more MPGN cases present initially as AKI than appreciated. Awareness of this possibility will increase the likelihood of early diagnosis and treatment. Based on the above discussion, the patient in case 2 should be treated promptly for the underlying B cell clone that is present in the bone marrow and affects the kidney. This is MGRS (monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance) and not MGUS anymore. Watchful waiting might lead to ESKD. Since there appears to be a secondary cause of MPGN in this case, steroids alone will not be sufficient. The correct answer is b.

Tumor Lysis Syndrome (TLS)

TLS is the most common oncologic emergency [55] with incidence as high as 26 % in high-grade B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia [56]. TLS results from rapid release of intracellular contents of dying cancer cells into the bloodstream either spontaneously or in response to cancer therapy . It is biochemically characterized by hyperuricemia, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hypocalcemia. Cardiac arrhythmias, seizures, and superimposed AKI are common clinical presentations. The pathophysiology of TLS-mediated AKI involves intratubular obstruction and inflammation by precipitation of crystals of uric acid, calcium phosphate and/or xanthine. Preexisting renal dysfunction favors intratubular crystal precipitation [57]. Consensus recommendations for TLS prophylaxis include volume expansion for all risk groups, use of allopurinol in medium- and high-risk groups, and use of recombinant urate oxidase (rasburicase) in high-risk groups [58]. Care should be taken, however, with use of this agent, which converts uric acid to allantoin, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen peroxide, since the latter can lead to methemoglobinemia and hemolytic anemia in individuals with glucose-6-phosphate deficiency. Utility of diuretics and urine alkalization are variable and their efficacy is debatable [58]. A chapter of this book has been devoted to TLS .

AKI Following Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT)

AKI is a common and consequential complication of HSCT. Causes of AKI following HSCT are divided into early onset (< 30 days) or late onset (> 3 months) [42]. Early AKI is commonly caused by sepsis, hypotension, and exposure to nephrotoxic agents [42]. Moreover, TLS and hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (HSOS) are also causes of early AKI with onset within 30 days of HSCT. Late onset AKI is often due to either thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) or calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) toxicity [15, 42] .

The incidence of AKI varies according to the type of HSCT: AKI is less frequent after autologous HSCT when compared to allogenic HSCT because the former patient is spared the nephrotoxicity of CNI, which is used for treating GVHD prophylaxis in the latter. Similarly, a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen is associated with lower risk of AKI than a myeloablative conditioning regimen because the former involves use of a less intense regimen and lower risk of HSOS.

The diagnosis of TMA is often delayed because many of its characteristic features— anemia, thrombocytopenia, AKI, elevated serum LDH—are nonspecific and are common findings in cancer patients post-HSCT in the absence of TMA. The presence of schistocytes and hypertension can be helpful but alone are not sufficient for a definitive diagnosis. A high index of suspicion is required for a diagnostic workup for TMA to be initiated. If a biopsy is done, it often shows mesangiolysis, GBM duplication, glomerular endothelial swelling, tubular injury and interstitial fibrosis [42, 59]. Except for atypical cases or situations where the management course would be altered, a kidney biopsy is often not required. Management of HSCT-associated TMA is supportive, and often involves discontinuation of CNIs—because CNIs are known to increase the risk of HSCT-associated TMA [42, 60] .

Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (HSOS) is characterized by sinusoidal and portal hypertension that result from radio-chemotherapy-induced endothelial cell injury of hepatic venules [60]. AKI develops in nearly 50 % of HSCT patients who develop HSOS [15, 42]. The pathophysiology of HSOS-associated AKI is similar to hepatorenal physiology, characterized by fluid-retention, sodium retention, low urinary sodium, peripheral edema, weight gain, and usually bland urine sediment. Notably, more than 70 % of patients with HSOS will recover spontaneously with only supportive care—managing sodium and water balance, augmenting renal perfusion, and relieving symptomatic ascites with repeated paracentesis [42, 61]. For details on HSCT-associated renal disease, refer to a related chapter in this book.

Chemotherapy with Nephrotoxicity

Chemotherapeutic agents that are associated with nephrotoxicity are listed in tabular form in Table 1.1. These chemotherapeutic classes include cytotoxic, platinumcontaining agents, alkylating agents, antitumor antibiotics, and antimetabolites. Detailed discussions of these chemotherapy agents are presented in another chapter of this book. Here we review some general features of their causal relationship with AKI .

Calcineurin Inhibitors (CNIs) Toxicity

In patients who have undergone allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplant, CNIs (cyclosporine and tacrolimus) are used for prevention of graft versus host disease (GVHD). Both of these medications cause AKI by causing renal vessel vasoconstriction and direct tubular toxicity, resulting in reduced GFR. The AKI is usually reversible with dose reduction. CNIs are also known, however, to cause progressive, irreversible CKD associated with tubuleinterstitial fibrosis in a striped pattern along medullary rays. These agents have also been implicated as risk factors for TMA [42, 62] .

Nephrotoxicity Associated with Platinum-Containing Agents

Platinum-based chemotherapeutic agents are important anticancer therapies. Cisplatin, the founding member of the group, is a simple inorganic compound consisting of an atom of platinum surrounded by chloride and ammonium atoms in cis position. Since its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1978 as a therapeutic agent, it has become one of the most frequently used chemotherapeutic agents, especially against solid tumors [63]. Its clinical use is limited by major toxicity (nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, ototoxicity, and myelosuppression) of which nephrotoxicity is the most serious and dose limiting [64]. One third of patients treated with cisplatin develop renal impairment within days following the initial dose [65]. The kidney’s vulnerability to cisplatin toxicity is thought to be due to its function as the principal excretory organ for platinum [66]. Because of its low molecular weight and uncharged state, cisplatin is freely filtered through the glomerulus as well as secreted by tubular epithelial cells [67], and accumulates in both the proximal and distal tubules where it exerts its nephrotoxic effects, especially at the S3 segment of the proximal tubule lying in the outer medulla [68, 69] .

Clinically, AKI caused by cisplatin is often nonoliguric and is characterized by tubular dysfunction, inability to concentrate urine, and inability to reabsorb magnesium—seen in > 50 % of patients treated with cisplatin [70]. Glucosuria, aminoaciduria, hypokalemia, hyponatremia, hypocalcemia, and hypochloeremia may also be present as additional evidence of tubular dysfunction [67]. Severe salt wasting can result in orthostatic hypotension and/or incomplete distal tubular acidosis in some patients [71]. The underlying pathophysiology of cisplatin-induced AKI is attributed to four types of injuries: (1) tubular toxicity, due to direct injury to epithelial cells; (2) vascular damage to small and medium size arteries, due to decreased renal blood flow because of obstruction and/or inflammation; (3) glomerular injury; and (4) interstitial injury, typical of long term cisplatin exposure [66]. The tubular injury is attributed to a complex, interconnected multifactorial process including enhanced accumulation of cisplatin via transport-mediated process [69], metabolic conversion of cisplatin to a nephrotoxin [72], DNA damage [73], dysregulated epithelial cell transporters activity, mitochondrial dysfunction [74], oxidative and nitrosative stress [75], as well as activation of proinflammatory signaling pathways such as NF-kB and MAPK pathways [66].

Risk factors of cisplatin nephrotoxicity include patient-related factors and drug related factors. The most important patient-related factors include age (especially, greater than 60 years old), female gender (have 2-fold higher risk as men), African-American race, malnourished/dehydrated state, preexisting renal insufficiency (GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73m2), and concomitant administration of nephrotoxic agents, reviewed in [66]. Cisplatin doses higher than 50 mg/m2, long-term exposure to cisplatin, as well as repeated exposure, are all associated with cisplatin-induced AKI [66, 68]. Newer platinum agents such as oxaliplatin, carboplatin, and nedaplatin appear to be less nephrotoxic than cisplatin. These are alternative agents, especially for patients at relatively high risk for AKI .

Nephrotoxicity Associated with Alkylating Agents

Ifosfamide and cyclophosphamide are used in conjunction with other chemotherapy to treat metastatic germ cell tumors and some sarcomas. Ifosfamide is a synthetic isomer of cyclophosphamide. Hemorrhagic cystitis is the predominant toxicity of both agents. Hyponatremia due to increased antidiuretic hormone activity is the primary renal-related adverse effect of cyclophosphamide [76], and it reverses promptly upon discontinuing the agent. Moreover, clinical nephrotoxicity is seen in up to 30 % of cases when Ifosfamide is used [77]. Subclinical glycosuria, evidence of proximal tubular toxicity, is reported in 90 % of patients in a pediatric study [78]. The nephrotoxicity of ifosfamide is attributed to the 40-fold greater quantity of chloroacetaldehyde produced from its metabolism relative to cyclophosphamide [77]. In vitro studies suggest that chloroacetaldehyde directly injures the proximal tubule causing type 2 renal tubular acidosis with Fanconi syndrome [79, 80]. While moderate declines in GFR may be seen, significant loss of GFR is not a major feature of ifosfamide AKI except if there is a concomitant use of cisplatin. The timing of the tubular dysfunction is variable [81], and it is generally reversible. However, in some cases decline in glomerular and tubular function may continue even after cessation of Ifosfamide [78]. Risk factors for Ifosfamide-induced AKI include cumulative dose (moderate to severe nephrotoxicity tend to occur with cumulative dose > 100 g/m2), age < 4–5 years old, and prior or concomitant cisplatin therapy [78, 82]. Therefore, limiting cumulative dose and avoiding concurrent use of cisplatin is a corner stone of preventing ifosfamide-induced nephrotoxicity.

Nephrotoxicity Associated with Antitumor Antibiotics

Mitomycin is an antitumor antibiotic with well-characterized renal toxicity. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome (TTP/HUS) is the most common nephrotoxicity associated with mitomycin C [83, 84]. The overall incidence is ranges from 2 to 28 % of patients depending on the cumulative dose [85, 86]. Renal failure due to mitomycin occurred in 2, 11, and 28 % of patients receiving cumulative doses of 50, 50–69, and > 70 mg/m2, respectively in one series [85]. Direct endothelial injury is the presumed inciting event [86, 87]). In rat model of mitomycin induced TTP/HUS, evidence of endothelial injury was obvious as early as 6 h following mitomycin infusion, and a clear picture of thrombotic microangiopathy has developed by day 7 postmitomycin infusion. However, in humans, the onset of clinical evidence of TTP/HUS is typically delayed more than 6 months following exposure to mitomycin [87]. The basis for the difference in the time of onset between animal model and human is unknown. Treatment with plasmapharesis [88, 89] or immunoabsorption of serum with a staphylococcal protein A column [90, 91] often reverses the kidney injury. Intractible cases have also been treated successfully with rituximab [92, 93].

Nephrotoxicity Associated with Antimetabolites

Antimetabolites, including purine analogs, pyrimidine analogs, and antifolate agents are commonly used chemotherapy agents.Nephrotoxicity is induced frequently by methotrexate (an antifolate agent), the best described toxicity associated with any of the antimetabolites . In one series, renal toxicity was reported in nearly 2 % of patient with osteosarcoma who were treated with high-dose methotrexate [94]. Methotrexate doses less that 0.5–1 g/m2 is often not associated with nephrotoxicity, baring preexisting renal failure. The pathogenesis of methotrexate induced kidney injury is multifactorial. At high dose, methotrexate and its metabolite, 7-hydroxymethotrexate can precipitate in renal tubules, resulting in tubular obstruction. The risk of such intratubular precipitation is heightened by acidic urine, and a volume depleted state. Urine alkalinization and volume expansion lower the risk of precipitation and are often employed as preventative measures. Drugs, including salicylates, probenecids, sulfisoxazole, penicillins, and NSAIDS competitively inhibit tubular secretion of methotrexate, thereby increasing the risk of tubular injury [95]. Methotrexate can also produce a transient decrease in GFR due to afferent arteriole constriction [96], which reverses upon cessation of the drug.

Risk Factors for Chemotherapy-Induced Nephrotoxicity

Patient risk factors for chemotherapy-induced nephrotoxicity include: older age, underlying AKI or CKD, pharmacogenetics favoring drug toxicity. Volume depletion can enhance innate drug toxicity due to increased drug or metabolite concentration in the kidney and may involve formation of intratubular crystals by insoluble drug or metabolites. Renal hypoperfusion can be due to decreased oral intake, over diuresis, chemotherapyinduced cardiomyopathy, malignant ascites, or pleural effusion [97]. Tumor-related factors predisposing to chemotherapy-induced nephrotoxicity include the presence of toxic tumor proteins such as with myeloma-related kidney injury, renal infiltration by lymphoma, and cancer-associated glomerulopathies .

Postrenal Causes

AKI associated with postrenal causes is often due to obstruction of urinary outflow secondary to calculus formation, metastatic abdominal/pelvic malignancy, hemorrhagic cystitis, neurogenic bladder, retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy or fibrosis . Once suspected, the diagnosis is often confirmed by imaging (ultrasound or computed tomography) with demonstration of bilateral hydronephrosis, or unilateral hydronephrosis in patients with single kidneys. In the setting of hypovolemia, acute/partial obstruction, and some cases of retroperitoneal fibrosis, imaging may be falsely negative. Diagnostic utility of biomarkers have been reported [98], but clinical applicability is yet to be established. Timely relief of the obstruction often reverses the AKI. Relative to prerenal and intrinsic renal, postrenal AKI is associated with a higher recovery rate [99] .

The Cost and Adverse Outcomes of AKI in Cancer Patients

Increased Mortality

The consequences of AKI in cancer patients are both immediate and long term in onset. Mortality is the most important consequence . A recent, RIFLE-based study from MD Anderson Cancer Center specifically examined the acute costs and outcomes of incident AKI in critically ill patients with cancer. Lahoti and coworkers reported that, among the 2398 ICU cancer patients enrolled in the study, patients who developed AKI during the course of their care had higher mortality relative to those who did not [4]. This is not unlike the known association of AKI and increased mortality among noncancer patients where AKI-related mortality rates are generally reported to be between 30 and 60 % [100]. What was most notable in the study was the close correlation between risk of mortality and the percent increase in serum creatinine from baseline, irrespective of cancer type. Cancer patients with ≥ 50 % change in serum creatinine concentration (risk), ≥ 100 % (injury), or ≥ 200 % or requiring dialysis (failure) had 60 day survival of 62, 45, and 14 %, respectively. A 10 % rise in creatinine increased the odds of 60-day mortality by 8 % [4]. Thus, the more severe the reduction in eGFR, the worse the outcome. The high mortality associated with AKI in cancer patients was supported by other studies [5, 101, 102] .

Higher Rate of Failure to Achieve Complete Remission

The incidence of AKI is associated with failure of cancer survivors to achieve complete remission of their cancer . Canet and coworkers recently reported that, among patients with high grade hematological malignancies who did not have preexisting CKD, complete remission rate at 6 months was 39 % compared to 68 % among cancer patients without AKI [5]. Similar to the relationship between mortality and RIFLE classification of AKI, the likelihood of complete remission declines according to percentage rise in creatinine, irrespective of the cause of the AKI. The only exception to this relationship is tumor lysis syndrome. The 6 month complete remission rate in patients with AKI due to TLS was similar to those of patients without AKI [5]. TLS is a marker of good tumor response to chemotherapy. Therefore, it is logical that when TLS is diagnosed, and treated early, the AKI will not prevent a better outcome due to more effective cancer therapy.

The link between AKI and incomplete cancer remission may be explained by an associated administration of suboptimal dose of chemotherapy—due to chemotherapy dose adjustment necessitated by declining GFR. The higher mortality of cancer patients with AKI may also have an independent contributory effect. Additional mechanisms, however, are also likely involved. When full dose chemotherapy was administered to patients with hematologic malignancies complicated by AKI (85.4 % of patients in) [5], the incidence of complete remission was still lower. The mechanism underlying this observation is not known. It is also possible that altered pharmacokinetics of chemotherapy in a patient with AKI may alter the response of the cancer to the agent .

AKI Increases the Cost of Hospitalization

The degree of increase in serum creatinine correlates with an increase in cost of hospitalization of cancer patients with AKI . Lahoti et al. showed that, compared to cancer patients without AKI, hospital cost increased by 0.16 % per 1 % increase in creatinine for cancer patients with incident AKI. Hospital costs increased by 21 % for cancer patients with AKI requiring dialysis [4] .

Increased Risk of CKD

There is a reciprocal relationship between AKI and CKD . Patients with CKD are at higher risk of developing AKI; but AKI also increases the risk of incident CKD as well as accelerates the progression of preexisting CKD [34, 35]. A recent meta-analysis of 13 studies shows that, compared to patients without AKI, patients with AKI had higher risk of developing CKD and ESKD with pooled adjusted hazard ratios of 8.8 and 3.1 [103]. Among long-term survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplant, AKI was associated with an increased risk of CKD (HR 1.7) [104]. A recent retrospective, longitudinal study of patients who survived more than 10 years after myoablative allogeneic HSCT showed a cumulative increased incidence of CKD which reached 34 % at 10 years. Acute kidney injury is a strong risk factor for development of CKD. Patients who did not have AKI did not develop CKD [105]. Also, the adjusted hazard ratio appeared to increase with the severity of AKI (based on AKIN classification). Patients are more likely to develop CKD in the first year following HSCT (15 %) than in any subsequent years [105]. The precise mechanism by which AKI accelerates CKD in humans is an area of ongoing active research with our understanding of the genesis of interstitial fibrosis as a central focus of study [106, 107]. Inhibition of this maladaptive fibrotic process is a focus of research focused on interrupting the link between AKI and CKD as well as CKD progression [108].

Recognizing that CKD is the most important risk factor for cardiovascular disease, progression to ESKD, infection, hospitalization and death [109–111], it is clear that preventing the development of CKD, by preventing AKI among cancer patients, is an important goal for nephrologists and oncologists .

Summary

This chapter highlights AKI as a common event among patients with cancer. Renal toxicity of chemotherapy agents , direct and indirect renal complication of malignancies themselves, as well as advancing age of patients with cancer all converge to increase the risk of kidney disease. Important prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal etiologies have been discussed. The cost and long-term implications of AKI in the context of cancer management are also discussed. Effective management of patients with cancer depends not only on the judicious use of ever emerging, potent chemotherapeutic agents, but also on learning how to better prevent and manage AKI, which often complicates such care. Future research should be aimed at developing noninvasive, sensitive, and specific biomarkers that could expedite early/timely diagnosis. Some patients with cancer seem more vulnerable to nephrotoxins than others. Therefore, research aimed at uncovering patient-specific vulnerability factors will be essential as we enter the age of personalized medicine. Lastly, we do not yet understand the mechanism by which AKI accelerates CKD progression. Progress in this area of research will significantly reduce the short and long-term consequences associated with AKI.

Abbreviations

- ACEI:

-

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- AKIN:

-

Acute kidney injury network

- ATN:

-

Acute tubular necrosis

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- CNI:

-

Calcineurin inhibitors

- ESKD:

-

End-stage kidney disease

- FSGS:

-

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

- GFR:

-

Glomerular filtration rate

- GVHD:

-

Graft versus host disease

- HSCT:

-

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- HSOS:

-

Hepatic sinusoidal obstructive syndrome

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- KDIGO:

-

Kidney disease improving global outcomes

- LIK:

-

Lymphomatous kidney infiltration

- MGUS:

-

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance

- MGRS:

-

Monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance

- MM:

-

Multiple myeloma

- MPGN:

-

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

- mTOR:

-

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- NSAID:

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- RIFLE:

-

Risk, injury, failure, loss, end-stage renal disease

- TLS:

-

Tumor lysis syndrome

- TMA:

-

Thrombotic microangiopathy

- TTP/HUS:

-

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome

- VOD:

-

Veno-occlusive disease

References

Fast Stats. An interactive tool for access to SEER cancer statistics. Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/faststats. Accessed 8. Jan 2013

Christiansen CF, Johansen MB, Langeberg WJ, Fryzek JP, Sorensen HT. Incidence of acute kidney injury in cancer patients: a Danish population-based cohort study. Eur J intern Med. 2011;22(4):399–406.

Salahudeen AK, Doshi SM, Pawar T, Nowshad G, Lahoti A, Shah P. Incidence rate, clinical correlates, and outcomes of AKI in patients admitted to a comprehensive cancer center. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(3):347–54.

Lahoti A, Nates JL, Wakefield CD, Price KJ, Salahudeen AK. Costs and outcomes of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients with cancer. J support Oncol. 2011;9(4):149–55.

Canet E, Zafrani L, Lambert J, Thieblemont C, Galicier L, Schnell D, et al. Acute kidney injury in patients with newly diagnosed high-grade hematological malignancies: impact on remission and survival. PloS ONE. 2013;8(2):e55870.

Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P. Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative w. Acute renal failure - definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care (London, England). 2004;8(4):R204–12.

Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care (London, England). 2007;11(2):R31.

Group KAW. KDIGO AKI Work Group: KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl 2012;2:1–138.

Kellum JA, Levin N, Bouman C, Lameire N. Developing a consensus classification system for acute renal failure. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2002;8(6):509–14.

Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(11):3365–70.

Selby NM, Crowley L, Fluck RJ, McIntyre CW, Monaghan J, Lawson N, et al. Use of electronic results reporting to diagnose and monitor AKI in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(4):533–40.

Darmon M, Ciroldi M, Thiery G, Schlemmer B, Azoulay E. Clinical review: specific aspects of acute renal failure in cancer patients. Crit Care (London, England). 2006;10(2):211.

Lameire N, Van Biesen W, Vanholder R. The changing epidemiology of acute renal failure. Nat Clin Pract. 2006;2(7):364–77.

Joannidis M, Metnitz PG. Epidemiology and natural history of acute renal failure in the ICU. Crit Care Clin. 2005;21(2):239–49.

Zager RA. Acute renal failure in the setting of bone marrow transplantation. Kidney Int. 1994;46(5):1443–58.

Gruss E, Bernis C, Tomas JF, Garcia-Canton C, Figuera A, Motellon JL, et al. Acute renal failure in patients following bone marrow transplantation: prevalence, risk factors and outcome. Am J Nephrol. 1995;15(6):473–9.

Parikh CR, McSweeney PA, Korular D, Ecder T, Merouani A, Taylor J, et al. Renal dysfunction in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Kidney Int. 2002;62(2):566–73.

Parikh CR, Schrier RW, Storer B, Diaconescu R, Sorror ML, Maris MB, et al. Comparison of ARF after myeloablative and nonmyeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(3):502–9.

Kersting S, Koomans HA, Hene RJ, Verdonck LF. Acute renal failure after allogeneic myeloablative stem cell transplantation: retrospective analysis of incidence, risk factors and survival. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39(6):359–65.

Liu H, Li YF, Liu BC, Ding JH, Chen BA, Xu WL, et al. A multicenter, retrospective study of acute kidney injury in adult patients with nonmyeloablative hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45(1):153–8.

Fadia A, Casserly LF, Sanchorawala V, Seldin DC, Wright DG, Skinner M, et al. Incidence and outcome of acute renal failure complicating autologous stem cell transplantation for AL amyloidosis. Kidney Int. 2003;63(5):1868–73.

Soares M, Salluh JI, Carvalho MS, Darmon M, Rocco JR, Spector N. Prognosis of critically ill patients with cancer and acute renal dysfunction. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(24):4003–10.

Darmon M, Thiery G, Ciroldi M, Porcher R, Schlemmer B, Azoulay E. Should dialysis be offered to cancer patients with acute kidney injury? Intensiv Care Med. 2007;33(5):765–72.

Stewart AF. Clinical practice. Hypercalcemia associated with cancer. New Engl J Med. 2005;352(4):373–9.

Izzedine H, Escudier B, Rouvier P, Gueutin V, Varga A, Bahleda R, et al. Acute tubular necrosis associated with mTOR inhibitor therapy: a real entity biopsy-proven. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol/ESMO. 2013;24(9):2421–5.

Regner KR, Roman RJ. Role of medullary blood flow in the pathogenesis of renal ischemiareperfusion injury. Curr Opin Nephrol hypertens. 2012;21(1):33–8.

Fagundes C, Pepin MN, Guevara M, Barreto R, Casals G, Sola E, et al. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as biomarker in the differential diagnosis of impairment of kidney function in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2012;57(2):267–73.

Huang Y, Don-Wauchope AC. The clinical utility of kidney injury molecule 1 in the prediction, diagnosis and prognosis of acute kidney injury: a systematic review. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2011;10(4):260–71.

Vaidya VS, Ozer JS, Dieterle F, Collings FB, Ramirez V, Troth S, et al. Kidney injury molecule-1 outperforms traditional biomarkers of kidney injury in preclinical biomarker qualification studies. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(5):478–85.

Amdur RL, Chawla LS, Amodeo S, Kimmel PL, Palant CE. Outcomes following diagnosis of acute renal failure in U.S. veterans: focus on acute tubular necrosis. Kidney Int. 2009;76(10):1089–97.

Brito GA, Balbi AL, Abrao JM, Ponce D. Long-term outcome of patients followed by nephrologists after an acute tubular necrosis episode. Int J Nephrol. 2012;2012:361528.

Grgic I, Campanholle G, Bijol V, Wang C, Sabbisetti VS, Ichimura T, et al. Targeted proximal tubule injury triggers interstitial fibrosis and glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2012;82(2):172–83.

Obrador GT, Price B, O’Meara Y, Salant DJ. Acute renal failure due to lymphomatous infiltration of the kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8(8):1348–54.

Richmond J, Sherman RS, Diamond HD, Craver LF. Renal lesions associated with malignant lymphomas. Am J Med. 1962;32:184–207.

Richards MA, Mootoosamy I, Reznek RH, Webb JA, Lister TA. Renal involvement in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: clinical and pathological features in 23 cases. Hematol Oncol. 1990;8(2):105–10.

Tornroth T, Heiro M, Marcussen N, Franssila K. Lymphomas diagnosed by percutaneous kidney biopsy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(5):960–71.

Cohen LJ, Rennke HG, Laubach JP, Humphreys BD. The spectrum of kidney involvement in lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(6):1191–6.

Alexanian R, Barlogie B, Dixon D. Renal failure in multiple myeloma. Pathogenesis and prognostic implications. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(8):1693–5.

Blade J, Fernandez-Llama P, Bosch F, Montoliu J, Lens XM, Montoto S, et al. Renal failure in multiple myeloma: presenting features and predictors of outcome in 94 patients from a single institution. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(17):1889–93.

Torra R, Blade J, Cases A, Lopez-Pedret J, Montserrat E, Rozman C, et al. Patients with multiple myeloma requiring long-term dialysis: presenting features, response to therapy, and outcome in a series of 20 cases. Br J Haematol. 1995;91(4):854–9.

Montseny JJ, Kleinknecht D, Meyrier A, Vanhille P, Simon P, Pruna A, et al. Long-term outcome according to renal histological lesions in 118 patients with monoclonal gammopathies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13(6):1438–45.

Lam AQ, Humphreys BD. Onco-nephrology: AKI in the cancer patient. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(10):1692–700.

Basnayake K, Cheung CK, Sheaff M, Fuggle W, Kamel D, Nakoinz S, et al. Differential progression of renal scarring and determinants of late renal recovery in sustained dialysis dependent acute kidney injury secondary to myeloma kidney. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63(10):884–7.

Raab MS, Podar K, Breitkreutz I, Richardson PG, Anderson KC. Multiple myeloma. Lancet. 2009;374(9686):324–39.

Augustson BM, Begum G, Dunn JA, Barth NJ, Davies F, Morgan G, et al. Early mortality after diagnosis of multiple myeloma: analysis of patients entered onto the United Kingdom Medical Research Council trials between 1980 and 2002-Medical Research Council Adult Leukaemia Working Party. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9219–26.

Haynes RJ, Read S, Collins GP, Darby SC, Winearls CG. Presentation and survival of patients with severe acute kidney injury and multiple myeloma: a 20-year experience from a single centre. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(2):419–26.

Eleutherakis-Papaiakovou V, Bamias A, Gika D, Simeonidis A, Pouli A, Anagnostopoulos A, et al. Renal failure in multiple myeloma: incidence, correlations, and prognostic significance. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48(2):337–41.

Greipp PR, San Miguel J, Durie BG, Crowley JJ, Barlogie B, Blade J, et al. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3412–20.

Haynes R, Leung N, Kyle R, Winearls CG. Myeloma kidney: improving clinical outcomes? Adv Chronic kidney Dis. 2012;19(5):342–51.

Audard V, Georges B, Vanhille P, Toly C, Deroure B, Fakhouri F, et al. Renal lesions associated with IgM-secreting monoclonal proliferations: revisiting the disease spectrum. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(5):1339–49.

Sanders PW, Herrera GA. Monoclonal immunoglobulin light chain-related renal diseases. Semin Nephrol. 1993;13(3):324–41.

Sethi S, Zand L, Leung N, Smith RJ, Jevremonic D, Herrmann SS, et al. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis secondary to monoclonal gammopathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(5):770–82.

Batal I, Bijol V, Schlossman RL, Rennke HG. Proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal immunoglobulin deposits in a kidney allograft. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(2):318–23.

Lorenz EC, Sethi S, Leung N, Dispenzieri A, Fervenza FC, Cosio FG. Recurrent membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis after kidney transplantation. Kidney Int. 2010;77(8):721–8.

Flombaum CD. Metabolic emergencies in the cancer patient. Semin Oncol. 2000;27(3):322–34.

Wilson FP, Berns JS. Onco-nephrology: tumor lysis syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(10):1730–9.

Seidemann K, Meyer U, Jansen P, Yakisan E, Rieske K, Fuhrer M, et al. Impaired renal function and tumor lysis syndrome in pediatric patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and B-ALL. Observations from the BFM-trials. Klinische Padiatrie. 1998;210(4):279–84.

Wilson FP, Berns JS. Tumor lysis syndrome: new challenges and recent advances. Adv chronic kidney Dis. 2014;21(1):18–26.

Cohen EP, Hussain S, Moulder JE. Successful treatment of radiation nephropathy with angiotensin II blockade. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55(1):190–3.

Parikh CR, Coca SG. Acute renal failure in hematopoietic cell transplantation. Kidney Int. 2006;69(3):430–5.

McDonald GB. Hepatobiliary complications of hematopoietic cell transplantation, 40 years on. Hepatology. 2010;51(4):1450–60.

Naesens M, Kuypers DR, Sarwal M. Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(2):481–508.

Taguchi T, Nazneen A, Abid MR, Razzaque MS. Cisplatin-associated nephrotoxicity and pathological events. Contrib Nephrol. 2005;148:107–21.

Barabas K, Milner R, Lurie D, Adin C. Cisplatin: a review of toxicities and therapeutic applications. Vet Comp Oncol. 2008;6(1):1–18.

Sahni V, Choudhury D, Ahmed Z. Chemotherapy-associated renal dysfunction. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(8):450–62.

Sanchez-Gonzalez PD, Lopez-Hernandez FJ, Lopez-Novoa JM, Morales AI. An integrative view of the pathophysiological events leading to cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2011;41(10):803–21.

Arany I, Safirstein RL. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Semin Nephrol. 2003;23(5):460–4.

Kawai Y, Taniuchi S, Okahara S, Nakamura M, Gemba M. Relationship between cisplatin or nedaplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and renal accumulation. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28(8):1385–8.

Kroning R, Lichtenstein AK, Nagami GT. Sulfur-containing amino acids decrease cisplatin cytotoxicity and uptake in renal tubule epithelial cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2000;45(1):43–9.

Lam M, Adelstein DJ. Hypomagnesemia and renal magnesium wasting in patients treated with cisplatin. Am J Kidney Dis. 1986;8(3):164–9.

Bearcroft CP, Domizio P, Mourad FH, Andre EA, Farthing MJ. Cisplatin impairs fluid and electrolyte absorption in rat small intestine: a role for 5-hydroxytryptamine. Gut. 1999;44(2):174–9.

Townsend DM, Deng M, Zhang L, Lapus MG, Hanigan MH. Metabolism of Cisplatin to a nephrotoxin in proximal tubule cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(1):1–10.

Saad AA, Youssef MI, El-Shennawy LK. Cisplatin induced damage in kidney genomic DNA and nephrotoxicity in male rats: the protective effect of grape seed proanthocyanidin extract. Food Chem Toxicol Int J Publ Br Ind Biol Res Assoc. 2009;47(7):1499–506.

Chang B, Nishikawa M, Sato E, Utsumi K, Inoue M. L-Carnitine inhibits cisplatin-induced injury of the kidney and small intestine. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;405(1):55–64.

Chirino YI, Pedraza-Chaverri J. Role of oxidative and nitrosative stress in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Exp Toxicol Pathol Off J Ges Toxikol Pathol. 2009;61(3):223–42.

Bressler RB, Huston DP. Water intoxication following moderate-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145(3):548–9.

Skinner R, Sharkey IM, Pearson AD, Craft AW. Ifosfamide, mesna, and nephrotoxicity in children. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(1):173–90.

Skinner R, Pearson AD, English MW, Price L, Wyllie RA, Coulthard MG, et al. Risk factors for ifosfamide nephrotoxicity in children. Lancet. 1996;348(9027):578–80.

Dubourg L, Michoudet C, Cochat P, Baverel G. Human kidney tubules detoxify chloroacetaldehyde, a presumed nephrotoxic metabolite of ifosfamide. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(8):1615–23.

Zamlauski-Tucker MJ, Morris ME, Springate JE. Ifosfamide metabolite chloroacetaldehyde causes Fanconi syndrome in the perfused rat kidney. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1994;129(1):170–5.

Stohr W, Paulides M, Bielack S, Jurgens H, Treuner J, Rossi R, et al. Ifosfamide-induced nephrotoxicity in 593 sarcoma patients: a report from the Late Effects Surveillance System. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(4):447–52.

Skinner R, Cotterill SJ, Stevens MC. Risk factors for nephrotoxicity after ifosfamide treatment in children: a UKCCSG Late Effects Group study. United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group. Br J Cancer. 2000;82(10):1636–45.

Cantrell JE, Jr., Phillips TM, Schein PS. Carcinoma-associated hemolytic-uremic syndrome: a complication of mitomycin C chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3(5):723–34.

Price TM, Murgo AJ, Keveney JJ, Miller-Hardy D, Kasprisin DO. Renal failure and hemolytic anemia associated with mitomycin C. A case report. Cancer. 1985;55(1):51–6.

Valavaara R, Nordman E. Renal complications of mitomycin C therapy with special reference to the total dose. Cancer. 1985;55(1):47–50.

Groff JA, Kozak M, Boehmer JP, Demko TM, Diamond JR. Endotheliopathy: a continuum of hemolytic uremic syndrome due to mitomycin therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29(2):280–4.

Cattell V. Mitomycin-induced hemolytic uremic kidney. An experimental model in the rat. Am J Pathol. 1985;121(1):88–95.

Garibotto G, Acquarone N, Saffioti S, Deferrari G, Villaggio B, Ferrario F. Successful treatment of mitomycin C-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome by plasmapheresis. Nephron. 1989;51(3):409–12.

Poch E, Almirall J, Nicolas JM, Torras A, Revert L. Treatment of mitomycin-C-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome with plasmapheresis. Nephron. 1990;55(1):89–90.

Snyder HW, Jr., Mittelman A, Oral A, Messerschmidt GL, Henry DH, Korec S, et al. Treatment of cancer chemotherapy-associated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome by protein A immunoadsorption of plasma. Cancer. 1993;71(5):1882–92.

von Baeyer H. Plasmapheresis in thrombotic microangiopathy-associated syndromes: review of outcome data derived from clinical trials and open studies. Ther Apheresis Off J Int Soc Apheresis Japanese Soc Apheresis. 2002;6(4):320–8.

Shah G, Yamin H, Smith H. Mitomycin-C-Induced TTP/HUS Treated Successfully with Rituximab: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Hematol. 2013;2013:130978.

Hong MJ, Lee HG, Hur M, Kim SY, Cho YH, Yoon SY. Slow, but complete, resolution of mitomycin-induced refractory thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura after rituximab treatment. Korean J Hematol. 2011;46(1):45–8.

Widemann BC, Balis FM, Kempf-Bielack B, Bielack S, Pratt CB, Ferrari S, et al. High-dose methotrexate-induced nephrotoxicity in patients with osteosarcoma. Cancer. 2004;100(10):2222–32.

Balis FM. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions of commonly used anticancer drugs. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1986;11(3):223–35.

Howell SB, Carmody J. Changes in glomerular filtration rate associated with high-dose methotrexate therapy in adults. Cancer Treat Rep. 1977;61(7):1389–91.

Perazella MA. Onco-nephrology: renal toxicities of chemotherapeutic agents. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(10):1713–21.

Urbschat A, Gauer S, Paulus P, Reissig M, Weipert C, Ramos-Lopez E, et al. Serum and urinary NGAL but not KIM-1 raises in human postrenal AKI. Eur J Clin Investig. 2014;44(7):652–9.

Yang F, Zhang L, Wu H, Zou H, Du Y. Clinical analysis of cause, treatment and prognosis in acute kidney injury patients. PloS ONE. 2014;9(2):e85214.

Ostermann M, Chang RW. Acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit according to RIFLE. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(8):1837–43; quiz 52.

Benoit DD, Vandewoude KH, Decruyenaere JM, Hoste EA, Colardyn FA. Outcome and early prognostic indicators in patients with a hematologic malignancy admitted to the intensive care unit for a life-threatening complication. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(1):104–12.

Benoit DD, Hoste EA, Depuydt PO, Offner FC, Lameire NH, Vandewoude KH, et al. Outcome in critically ill medical patients treated with renal replacement therapy for acute renal failure: comparison between patients with and those without haematological malignancies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(3):552–8.

Coca SG, Singanamala S, Parikh CR. Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int. 2012;81(5):442–8.

Hingorani S, Guthrie KA, Schoch G, Weiss NS, McDonald GB. Chronic kidney disease in long-term survivors of hematopoietic cell transplant. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39(4):223–9.

Shimoi T, Ando M, Munakata W, Kobayashi T, Kakihana K, Ohashi K, et al. The significant impact of acute kidney injury on CKD in patients who survived over 10 years after myeloablative allogeneic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(1):80–4.

Yang L, Humphreys BD, Bonventre JV. Pathophysiology of acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease: maladaptive repair. Contrib Nephrol. 2011;174:149–55.

Humphreys BD, Xu F, Sabbisetti V, Grgic I, Naini SM, Wang N, et al. Chronic epithelial kidney injury molecule-1 expression causes murine kidney fibrosis. J Clin Investig. 2013;123(9):4023–35.

Yang L, Besschetnova TY, Brooks CR, Shah JV, Bonventre JV. Epithelial cell cycle arrest in G2/M mediates kidney fibrosis after injury. Nat Med. 2010;16(5):535–43, 1p following 143.

Shlipak MG, Fried LF, Cushman M, Manolio TA, Peterson D, Stehman-Breen C, et al. Cardiovascular mortality risk in chronic kidney disease: comparison of traditional and novel risk factors. JAMA. 2005;293(14):1737–45.

James MT, Quan H, Tonelli M, Manns BJ, Faris P, Laupland KB, et al. CKD and risk of hospitalization and death with pneumonia. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54(1):24–32.

Cohen EP, Piering WF, Kabler-Babbitt C, Moulder JE. End-stage renal disease (ESKD)after bone marrow transplantation: poor survival compared to other causes of ESKD. Nephron. 1998;79(4):408–12.

Peterson BA, Collins AJ, Vogelzang NJ, Bloomfield CD. 5-Azacytidine and renal tubular dysfunction. Blood. 1981;57(1):182–5.

Kamal AH, Bull J, Stinson CS, Blue DL, Abernethy AP. Conformance with supportive care quality measures is associated with better quality of life in patients with cancer receiving palliative care. J Oncol Pract/Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2013;9(3):e73–6.

Kyle RA, Yee GC, Somerfield MR, Flynn PJ, Halabi S, Jagannath S, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 clinical practice guideline update on the role of bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(17):2464–72.

Eremina V, Jefferson JA, Kowalewska J, Hochster H, Haas M, Weisstuch J, et al. VEGF inhibition and renal thrombotic microangiopathy. New Engl J Med. 2008;358(11):1129–36.

Izzedine H, Rixe O, Billemont B, Baumelou A, Deray G. Angiogenesis inhibitor therapies: focus on kidney toxicity and hypertension. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50(2):203–18.

Fakih M. Management of anti-EGFR-targeting monoclonal antibody-induced hypomagnesemia. Oncology. 2008;22(1):74–6.

Muallem S, Moe OW. When EGF is offside, magnesium is wasted. J Clin Investig. 2007;117(8):2086–9.

Meyer KB, Madias NE. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Miner Electrolyte Metab. 1994;20(4):201–13.

Cornelison TL, Reed E. Nephrotoxicity and hydration management for cisplatin, carboplatin, and ormaplatin. Gynecol Oncol. 1993;50(2):147–58.

Santoso JT, Lucci JA, 3rd, Coleman RL, Schafer I, Hannigan EV. Saline, mannitol, and furosemide hydration in acute cisplatin nephrotoxicity: a randomized trial. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;52(1):13–8.

Asna N, Lewy H, Ashkenazi IE, Deutsch V, Peretz H, Inbar M, et al. Time dependent protection of amifostine from renal and hematopoietic cisplatin induced toxicity. Life Sci. 2005;76(16):1825–34.

Glezerman I, Kris MG, Miller V, Seshan S, Flombaum CD. Gemcitabine nephrotoxicity and hemolytic uremic syndrome: report of 29 cases from a single institution. Clin Nephrol. 2009;71(2):130–9.

Husband DJ, Watkin SW. Fatal hypokalaemia associated with ifosfamide/mesna chemotherapy. Lancet. 1988;1(8594):1116.

Colovic M, Jurisic V, Jankovic G, Jovanovic D, Nikolic LJ, Dimitrijevic J. Interferon alpha sensitisation induced fatal renal insufficiency in a patient with chronic myeloid leukaemia: case report and review of literature. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59(8):879–81.

Markowitz GS, Nasr SH, Stokes MB, D’Agati VD. Treatment with IFN-{alpha}, -{beta}, or -{gamma} is associated with collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(4):607–15.

Guleria AS, Yang JC, Topalian SL, Weber JS, Parkinson DR, MacFarlane MP, et al. Renal dysfunction associated with the administration of high-dose interleukin-2 in 199 consecutive patients with metastatic melanoma or renal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(12):2714–22.

Mercatello A, Hadj-Aissa A, Negrier S, Allaouchiche B, Coronel B, Tognet E, et al. Acute renal failure with preserved renal plasma flow induced by cancer immunotherapy. Kidney Int. 1991;40(2):309–14.

Abelson HT, Fosburg MT, Beardsley GP, Goorin AM, Gorka C, Link M, et al. Methotrexateinduced renal impairment: clinical studies and rescue from systemic toxicity with high-dose leucovorin and thymidine. J Clin Oncol. 1983;1(3):208–16.

Lesesne JB, Rothschild N, Erickson B, Korec S, Sisk R, Keller J, et al. Cancer-associated hemolytic-uremic syndrome: analysis of 85 cases from a national registry. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7(6):781–9.

Weiss RB. Streptozocin: a review of its pharmacology, efficacy, and toxicity. Cancer Treat Rep. 1982;66(3):427–38.

Kramer RA, McMenamin MG, Boyd MR. In vivo studies on the relationship between hepatic metabolism and the renal toxicity of 1-(2-chloroethyl)-3-(trans-4-methylcyclohexyl)-1-nitrosourea (MeCCNU). Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1986;85(2):221–30.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Olabisi, O., Bonventre, J. (2015). Acute Kidney Injury in Cancer Patients. In: Jhaveri, K., Salahudeen, A. (eds) Onconephrology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2659-6_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2659-6_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4939-2658-9

Online ISBN: 978-1-4939-2659-6

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)