Abstract

The development of evidence-based quality measures and benchmarks in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening is a critical step toward building a truly accountable health-care system. Indeed, much of the gastroenterology research literature in quality has focused on the scientific merit and reliability of these measures. Less attention has been placed on understanding the use of these measures for physician evaluation, an equally important part of the performance measurement and improvement cycle. In this chapter, we will address this information gap by reviewing the use of CRC quality measurement for physician evaluation. Our focus first includes the levers available for action in performance evaluation including physician feedback, pay for performance, public reporting, and physician designation programs including tiered provider networks. Second, we review existing evaluation systems in the government, commercial, regional, and integrated delivery systems. Third, we review limitations of these existing systems including the overreliance on process measures and rates of testing over outcomes, the difficulty in developing information systems to accommodate measurement, and the implications of physician resistance in the management and success of these programs. Finally, we conclude with recommendations for special societies to take and support the development of a quality improvement system that meets the needs of a modern learning health-care system.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Performance measurement

- Learning health care

- Pay for performance

- PQRS

- Physician designation

- Tiered provider networks

- Public reporting

Introduction

The development of evidence-based quality measures and benchmarks in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening is a critical step toward building a truly accountable health-care system [1]. Indeed, much of the gastroenterology research literature in quality has focused on the scientific merit and reliability of these measures. Less attention has been placed on understanding the use of these measures for physician evaluation, an equally important part of the performance measurement and improvement cycle [2].

In qualitative work performed in the past decade, Scanlon et al. acknowledged this limitation, noting that very few studies have focused on understanding the impact of performance measurement in practice [3]. Initially, measurement reports were used primarily to reduce cost and manage utilization at the system level [4]. More recently and with increasing frequency, organizations are using individual physician feedback reports for quality improvement. This change has been catalyzed by three main factors: the growth of financial incentive programs geared toward individual providers; the development of robust physician-level quality measures; the improvement in data systems to allow more efficient and timely access to individual physician-level data.

Scanlon et al. focused primarily on the use of the health plan employer data and information set (HEDIS) and consumer assessment of health plans survey (CAHPS), both of which are still widely in use today. In fact, in 2012, more than 1000 health plans, covering the lives of more than 125 million Americans, reported HEDIS measures [5, 6]. CRC screening rates were added to HEDIS measures in 2006. Since the development of the HEDIS performance measure on CRC screening rates, a number of more detailed quality measures have emerged for CRC screening and surveillance. There is very little existing literature on the use of these newer measures for physician evaluation or on their impact on improving quality care in gastroenterology. In fact, a recent evidence report by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) on CRC screening found no published papers monitoring the quality of CRC screening at the population level; the bulk of effort in CRC screening has focused on increasing the use of screening, quality aside [7].

In this chapter, we will address this information gap by reviewing the use of CRC quality measurement for physician evaluation. Our focus will include the levers available for action in performance evaluation including evidence underlying these levers, examples of existing evaluation systems in government, commercial, regional, and integrated delivery systems, and the limitations of existing evaluation systems.

Levers for Action

In a recent perspective piece, authors from the Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, and AHRQ outlined a number of key goals for a modern quality measurement system (Table 8.1) [8]. The authors note that a quality measurement system has to be agile, broad-based, feasible, impactful, supportive of feedback, and vertically aligned. These goals build upon findings from earlier qualitative work by Scanlon et al. where managers of managed care organizations identified a number of shared characteristics of useful performance measures: relevant, actionable, timely, standardized, stable for trending, focused on the appropriate unit of analysis, and affordable [3].

Common to these frameworks is the importance of developing actionable measures for performance improvement. Action can take a number of forms, including performance feedback, pay for performance , public reporting, and physician designation . Each of these will be discussed separately below.

Performance Feedback

There are a number of theories as to how performance feedback can improve the quality of health-care practice. These include changing awareness about current practices, changing social norms, enabling self-efficacy, and facilitating goal setting [9]. The evidence suggests that “audit and feedback” approaches generally result in improvement in practice, and the degree of improvement depends on an individual’s performance at baseline and the type of feedback provided [9]. For example, feedback has been shown to be more effective when it is provided by a supervisor or a colleague, when it is provided more than once, when it is provided in both verbal and written form, and when it provides unambiguous targets for action.

At the population level, the rate of CRC screening uptake is a key measure used in performance feedback systems. Studies have shown that assessment and feedback of provider performance in CRC screening leads to improved performance [10, 11]. As it relates to colonoscopy quality, a number of studies have examined the impact of performance feedback on quality measures, and the majority have shown no impact on polyp detection rates [12]. However, three studies deserve mention. The first described an intervention that combined audible withdrawal timer with improved inspection technique [13]. This feedback intervention resulted in a significant increase in the detection of polyps as well as an overall population-level increase in the detection of advanced adenomas. In a recent study in the Veterans Health Administration, a quarterly report card resulted in a significant increase in adenoma detection and cecal intubation rates [14]. In a third study, an educational intervention combined with monthly feedback of adenoma detection rates resulted in marked improvement in detection rates during the course of the intervention [15]. Of note, none of these studies found a significant increase in advanced adenoma detection among physicians. More importantly, none have been able to assess the impact on the truly meaningful outcome, namely CRC incidence.

Pay for Performance

Tying financial incentives to performance feedback is one potential mechanism to augment the impact of physician feedback programs . Pay-for-performance (P4P) programs are in place for traditional Medicare inpatient and Medicare advantage plans, where withholds for nonparticipation will be implemented for individual physicians beginning in 2015. The individual physician program is based on the physician quality reporting system (PQRS) which has been in place since 2007 [16]. The physician value-based payment modifier (VBPM) will initially encourage participation but will quickly expand to incentivize performance on a defined set of measures [17].

Evidence on the impact of P4P programs is mixed [16]. Robust assessments of the impact of these interventions are lacking, and it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions from the existing literature [18]. The lack of impact of P4P programs may be related to inadequate incentive size, incentive structures, and even the choice of metrics themselves [19].

Dedicated studies evaluating the impact of P4P in CRC screening are not available although the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) has identified a set of principles for the development and evaluation of these programs [20]. Furthermore, others have outlined recommendations for the use of payment reform to improve colonoscopy quality [21]. Several CRC screening quality measures are included in the government’s P4P program and will be further described below .

Public Reporting

The belief that public reporting will result in improved quality is based on the notion that, in a competitive marketplace, information disclosure will cause self-regulation of the health-care system through actions on purchasers, consumers, policymakers, providers, and the public [22]. There are success stories in the general medical literature [23, 24], but the quality of the data is insufficient to make any broad conclusions on the impact of public reporting on consumer behavior, provider behavior, or clinical outcomes in health care [25, 26]. Furthermore, physicians are wary of public reporting programs because of concerns that these programs will distract the public from paying attention to the unmeasured components of health-care quality and will cause providers to avoid high-risk patients or perhaps even lower the quality of care through unintended consequences [27, 28].

In CRC screening, there are a few studies examining the impact of public reporting on the quality of care. Sarfaty and Myers found that the addition of a CRC screening rate to the HEDIS measures resulted in a number of changes by Pennsylvania health plans to increase screening rates in their populations [29]. This is notable because very few health plans had comprehensive management of CRC screening programs before that time [30]. The impact of public reporting of other quality measures in CRC screening is yet to be determined as many of these measures are still in their developmental stages.

Physician Designation

One particular method of public reporting is the use of “physician designation” programs. These are programs that rate, rank, or tier health-care providers based on measures of quality and cost with the hopes of directing patients to the preferred providers . One of the earliest attempts at physician designation was the creation of preferred provider organizations (PPO), where physicians were either in or out of the network [31]. These networks surged in popularity in the late 1990s to early 2000s and remain as the predominant option for commercial payers, but have failed to deliver substantive cost or quality improvements [32].

More recent attempts at physician designation have relied on more sophisticated criteria of quality and cost, balancing performance feedback with elements of public reporting. Key to the success of these programs is the accuracy of information provided to the public, and accuracy has been one of the concerns prompting legal action around physician designation. One early example is action taken by the Attorney General of New York in 2007 [33]. In response to attempts by insurers to tier physicians on quality and cost-efficiency, the NY Attorney General initiated an investigation that lead to a wide-reaching agreement with a number of insurers to create a core set of principles for the accuracy and transparency of data used for physician tiering .

In 2008, Colorado enacted legislation-requiring standards and procedures for health insurers that are initiating physician-rating systems [31]. The Physician Designation Disclosure Act has a number of key requirements: first, the law requires that any public reporting or ranking of a physician’s performance must include quality of care data; second, performance measures used in the ranking must be endorsed by the National Quality Forum , a national physician-specialty group or the Colorado Clinical Guidelines Collaborative and be measured in a statistically sound fashion; third, the rating must include a disclaimer advising patients not to rely solely on the ranking in choosing a physician; finally, the law gives physicians right to review the data on which his/her ranking is based and to take action should they feel the data misrepresent their practice. Similar legislation has been considered in a number of other states, including Oklahoma, Maryland, and Texas .

The impact of these programs on quality and cost of CRC screening remains unknown. In part, it is unclear to what extent differentiation of providers using existing performance metrics will impact the quality of care. Furthermore, physician cost profiling has been shown to be unreliable [34], and it remains to be seen how cost transparency will influence patient and physician behavior .

Existing Evaluation Systems

Using performance feedback, P4P, public reporting, and physician designation as the levers of action, a number of entities in the USA use CRC screening quality measures for physician evaluation. In this section, we will review a number of these programs with a specific focus on government, commercial, and regional programs as well as those of integrated delivery systems.

Government

As discussed above, the PQRS is a P4P program that has been the primary government-level evaluation program geared toward physicians. In 2011, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) paid more than US$ 261 million to 26,515 practices, which included 266,521 providers [35]. Included in this amount were 2370 gastroenterologists who participated in the program, representing 26.1 % of the eligible professionals. This number is quite small when compared to the 41,998 internists and family practice physicians who participated in the program in 2011. However, it represents a significant increase since only 8.1 % of the eligible gastroenterologists participated in 2008.

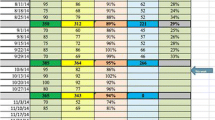

The tenth most commonly individual reported measure in the PQRS system among all providers was the CRC screening (Measure #113) measure. For gastroenterologists, the most commonly reported individual measures are listed in Table 8.2. PQRS measures around CRC screening for the 2013 reporting year are listed in Table 8.3. Screening colonoscopy adenoma detection rate (ADR) has been proposed by CMS for incorporation in the performance year 2014 and several new measures have been proposed by the gastrointestinal (GI) societies for 2015, including: repeat colonoscopy due to poor bowel preparation, and appropriate age for CRC screening [36].

To date, all current CRC quality measures (CRC screening rates, ADR detection rates, surveillance intervals after normal screening, and after adenomatous polyps) are process measures. Questions have arisen as to whether the existing CRC quality measures are satisfactory, or should be revised in view of updated recommendations from the special societies regarding surveillance intervals after polypectomy [37] as evidenced by the National Quality Forum’s August 2013 decision to not endorse measure 0659 (Endoscopy/polyp surveillance: colonoscopy interval for patients with a history of adenomatous polyps—avoidance of inappropriate use) [38].

The lack of outcome measures for gastroenterology has been cited as a concern with the existing measures. In response, CMS has contracted with Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation (CORE) to develop administrative claims-based, risk-adjusted measures of high-acuity care visits after an outpatient colonoscopy or endoscopy procedure. High-acuity care visits are defined as inpatient admissions, observation stays, or emergency department visits, and may represent complications due to outpatient procedures [39]. A technical expert panel was convened in 2013, with the objective of developing measures by 2014 that can be used to measure and improve the quality of care provided to Medicare beneficiaries, and to potentially submit these measures to the National Quality Forum for endorsement.

In addition to process measures of quality, government programs have begun to transition to value-based incentive programs. As gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures as a whole make up the largest percentage (32.7 %) of ambulatory surgical center (ASC) claims in Medicare, gastroenterologists will have a key stake in this process through the development of Medicare’s value-based purchasing program for ASCs. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) proposed three gastroenterology-specific measures for this program: (1) Appropriate follow-up interval for normal colonoscopy in average risk patients, (2) colonoscopy interval for patients with a history of adenomatous polyps—avoidance of inappropriate use, and (3) comprehensive colonoscopy documentation [40].

Commercial

As with government programs, commercial entities are focusing on value over cost or quality alone. Most commercial programs use physician designation programs based on physician quality and cost to evaluate physicians and incentivize patient behavior. A sample of these programs is represented in Table 8.4. All of the programs reviewed, start with quality designation and augment designation based on cost. These programs use proprietary software to group claim data into episodes of care when considering cost. The criteria for meeting quality and cost designations vary among programs and several entities rely on commercial vendors with proprietary ranking technology to calculate claim-based measures.

Very few commercial payor programs include gastroenterology in their rankings and even fewer contain measures specific to CRC screening. For example, the Aetna Aexcel Program uses expected rate of readmissions and hospital complications for satisfying claim-based measures of quality in gastroenterology [43]. Cigna Care Designation has more robust quality measures for inflammatory bowel disease and Hepatitis C but none for CRC screening specific to gastroenterology [44]. The BlueCross BlueShield of Massachusetts Alternative Quality Contract measures CRC screening rates, but does not specifically rank gastroenterologists [45]. One of the only programs to specifically address colonoscopy quality is the BlueCross BlueShield of North Carolina Tiered Provider Network [46], which uses a commercial software vendor to calculate postcolonoscopy complication rates and requires attestation of a quality management program for colonoscopy through either GIQuIC (http://giquic.gi.org/) or the AGA Digestive Health Recognition Program (http://www.gastro.org/practice/quality-initiatives/aga-digestive-health-recognition-program).

The impact of commercial designation programs on improving the quality or lowering the cost of care has not yet been publicly reported. As quality benchmarks remain crude in many clinical areas, these programs have an impact primarily by increasing competition on cost; this competition will vary based on market penetration. The proportion of physicians in a particular market who have designation ranking can vary based on program and market. As an example, the percent of designated physicians for the Cigna Care Designation Program ranges from a low of 15.1 % in Northern California to a high of 61.3 % in Pittsburgh [44].

Regional

As with commercial measures, most existing regional evaluation systems for health-care quality focus on screening rates as the primary measure of quality in CRC screening. For example, the Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality (http://www.wchq.org) has measured CRC screening rates at the hospital, group, and clinic level since 2005. This program reported a statistically significant improvement in CRC screening rates between 2006 and 2009; although this improvement was not beyond what would have been expected by looking at comparative groups [47]. Through a survey of program participants, it was clear that the specific choice of measure and the group’s performance on this measure relative to peers prioritized quality improvement efforts by any one medical group. A number of other nonprofit entities measure CRC screening rates such as Minnesota Community Measurement (http://mncm.org), Massachusetts Health Quality Partners (http://www.mhqp.org), and the New York City Colon Cancer Control Coalition (http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/living/cancer-colon-provider-coaltion.shtml).

One unique regional effort to use CRC quality measures for physician evaluation is Quality Quest for Health (http://www.qualityquest.org/). Through this initiative, a group of gastroenterologists, pathologists, and surgeons developed a Colonoscopy Best Care Index that incorporates eight components of a high-quality colonoscopy: (1) appropriate indication, (2) pre-procedure medical risk assessment, (3) bowel preparation, (4) complete examination, (5) photo-documentation of the cecum, (6) complete polyp information recorded, (7) withdrawal time recorded, (8) appropriate follow up recommended, and (9) no serious complications. The index score and adenoma detection rates are publically reported for participating physicians in central Illinois.

Integrated Delivery Systems

The largest integrated health-care delivery system in the USA is the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). The VHA’s current assessment of CRC screening quality includes HEDIS measurement of screening rate reported at the facility level [48]. In contrast to the government, commercial, and regional programs, the VHA’s program also tracks timeliness of care in CRC screening, including time from positive fecal-occult blood test (FOBT) to colonoscopy [49]. More robust measurement systems for colonoscopy quality are currently under development [50].

Kaiser Permanente of Northern California is a large integrated health delivery system with an organized CRC screening and evaluation program in place since the 1960s [51]. The current CRC screening evaluation system is focused at the medical center level and reports on: (1) CRC screening rates, (2) colonoscopy access times, (3) FOBT follow-up rates, and (4) cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis and survival [52]. The latter is unique among health-care systems given its focus on truly impactful outcomes. Individual process measures such as adenoma detection rates are also available for physicians performing endoscopy in each of these facilities. Additional colonoscopy-specific process measures are currently under development [53].

Limitations of Evaluation Systems

Over 15 years ago, McGlynn described six challenges to developing a quality monitoring strategy in health care (Table 8.5) [54]. Many of the same challenges to quality measurement in health care continue to exist today, illustrating the difficulty in overcoming these challenges. Specific examples in CRC screening are illustrative. As an example of the difficulty in establishing clinical criteria, clinical guidelines for CRC screening differ between medical societies. Guidelines released by the US Preventative Services Task Force, the Multi-Society Task Force, the American College of Gastroenterology, and the American College of Physicians among others differ in their recommendations in a number of parameters (see Chap. 2). It is very difficult to hold providers, health systems, or populations accountable for the quality of screening when recommendations regarding screening differ. Even more problematic are the issues raised by Walter et al. relating to the difficulty of converting practice guidelines into performance measures [55]. Guidelines do not consider important issues such as illness severity, provider judgment, or patient preference in determining appropriateness of care. As such, selecting indicators for reporting must be separated from the guideline writing process.

Another challenge outlined by McGlynn is the selection of appropriate indicators for reporting. In CRC screening, one of the most difficult challenges to overcome is the inability to measure clinically relevant outcomes, namely CRC incidence, because of the difficulty in linking screening data with outcome data. Kaiser Permanente of Northern California is one of the few programs that overcame this challenge by systematically including CRC incidence in its evaluation of medical centers within its system.

Kaiser’s evaluation system highlights the importance of developing robust information systems to support quality monitoring. When these data systems do not exist, is it acceptable to use process measures as proxies for the outcome of interest? In CRC screening, the use of adenoma detection rate (ADR) has been widely promulgated as a process measure for CRC screening quality. Recent evidence has linked ADR with CRC incidence [56], although it remains unclear if this relationship holds at all levels of ADR [57]. Even more challenging is when the optimal, evidence-based process measure (i.e., ADR) cannot be used due to inadequate data systems and physician evaluation relies on more feasible proxy measures (e.g., polyp detection rate).

Another potential limitation of evaluation systems relates to the issue of accountability as outlined by McGlynn. As discussed above, although most evaluation systems focus on the health system or provider group as the level of accountability, individual physician performance is increasingly targeted for evaluation. Physician concerns regarding legal liability as a result of performance measurement may limit enthusiasm for this level of accountability, although likelihood of the use of these measures in medical malpractice cases is low [58]. Physician resistance to evaluation will limit the usefulness of a voluntary system and perhaps corrupt a mandatory system through the avoidance of the sickest patients [28].

These challenges confront ongoing efforts to develop quality management programs in CRC screening and the sustainability of any particular program depends on the extent to which it can overcome these challenges. In their perspective piece, Conway et al. outline several critical steps to overcome these challenges and maximize the benefit of quality measurement. These include: first, a reduction in the complexity and burden of clinical data measurements; second, the creation of automated data collection systems for patient-reported outcomes; third, improved interoperability of data so that traditionally unstructured data such as laboratory data or pathology reports can more easily be queried; finally, improved consistency among electronic health records in calculating quality measures [8].

Conclusions

At present, the majority of quality management programs in CRC screening focus on maximizing the proportion of a given population undergoing screening tests. Of less importance is the quality of that individual test, perhaps reinforcing the adage widely quoted in gastroenterology circles: “The best test for CRC screening is the one that gets done” [59].

Moving beyond process measures of procedure utilization and focusing more on the quality and value of those services is critical to creating an agile, broad-based, feasible, impactful, and vertically aligned quality measurement system that supports provider feedback. Furthermore, understanding the impact of quality measurement on practice will also ensure that unintended consequences of reporting quality are appropriately managed or avoided. These steps will require collaboration between physicians, health system administrators, government agencies, industry representatives such as electronic health record and endoscopy report writer vendors and payors. Integrating patients into the process can be equally important in understanding how to create measures that are truly impactful.

GI societies are optimally positioned to coordinate this collaboration through a number of actions that mirror the recommendations of Conway et al.: first, support the development of scientifically sound quality metrics, including patient-reported outcomes and cost measures; second, advocate for the interoperability of information systems, including endoscopy report writers, pathology databases, and patient-feedback systems; third, continue development of agile registries with low barriers to entry that respond to immediate needs of physicians and provider groups; finally, to support the development of decision-support tools for process improvement. Through these collaborations, we can move CRC screening closer toward a truly learning health-care system [60].

References

Lieberman D. Quality in medicine: raising the accountability bar. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(3):561–6.

Dorn SD. Gastroenterology in a new era of accountability: part 2. Developing and implementing performance measures. Clin Gastro Hep. 2011;9(8):660–4.

Scanlon DP, et al. The role of performance measures for improving quality in managed care organizations. Health Serv Res. 2001;36(3):619–41.

Teleki SS, et al. Providing performance feedback to individual physicians: current practice and emerging lessons. 2006 August 10, 2013. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/working_papers/2006/RAND_WR381.pdf. Accessed 17 Sept 2014.

National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). The state of health care quality: reform, the quality agenda, and resource use; 2010. http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/State%20of%20Health%20Care/2010/SOHC%202010%20-%20Full2.pdf. Accessed 17 Sept 2014.

National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). The state of health care quality 2012: focus on obesity and on medicare plan improvement; 2012. http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/State%20of%20Health%20Care/2012/SOHC_Report_Web.pdf. Accessed 17 Sept 2014.

Holden DJ, et al. Enhancing the use and quality of colorectal cancer screening. In: Evidence reports/technology assessments, no. 190. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010.

Conway P, Mostashari F, Clancy C. The future of quality measurement for improvement and accountability. JAMA. 2013;309(21):2215–6.

Ivers N, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD000259.

Sabatino SA, et al. Interventions to increase recommendation and delivery of screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers by healthcare providers: systematic reviews of provider assessment and feedback and provider incentives. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(Suppl 1):S67–74.

Brouwers MC, et al. What implementation interventions increase cancer screening rates? A systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011;6:111. doi:10.1186/1748–5908–6–111.

Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR. Can we improve adenoma detection rates? A systematic review of intervention studies. Gastrointest Endos. 2011;74(3):656–65.

Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Greenlaw RL. Effect of a time-dependent colonoscopic withdrawal protocol on adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. Clin Gastro Hep. 2008;6:1091–8.

Kahi CJ, et al. Impact of a quarterly report card on colonoscopy quality measures. Gastrointest Endos. 2013;77(6):925–31.

Coe SG, et al. An endoscopic quality improvement program improves detection of colorectal adenomas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(2):219–26.

Ryan AM, Damberg CL. What can the past of pay-for-performance tell us about the future of value-based purchasing in medicare? Healthcare. 2013;1(1–2):42–9.

VanLare JM, Blum JD, Conway PH. Linking performance with payment: implementing the physician value-based payment modifier. JAMA. 2012;308(20):2089–90.

Scott A, et al. The effect of financial incentives on the quality of health care provided by primary care physicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Sep 7;(9):CD008451.

Jha AK. TIme to get serious about pay for performance. JAMA. 2013;309(4):347–8.

Johnson DA. Pay for performance: ACG guide for physicians. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(10):2119–22.

Hewett DG, Rex DK. Improving colonoscopy quality through health-care payment reform. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(9):1925–33.

Lansky D. Improving quality through public disclosure of performance information. Health Aff. 2002;21(4):52–62.

Joynt KE, Blumenthal DM, Orav EJ, Resnic FS, Jha AK. Association of public reporting for percutaneous coronary intervention with utilization and outcomes among medicare beneficiaries with acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2012;308(14):1460–8.

Smith MA, et al. Public reporting helped drive quality improvement in outpatient diabetes care among Wisconsin physician groups. Health Aff. 2012;31(3):570–7.

Fung CH, et al. Systematic review: the evidence that publishing patient care performance data improves quality of care. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(2):111–23.

Ketelaar NA, et al. Public release of performance data in changing the behaviour of healthcare consumers, professionals or organisations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011; (11):CD004538.

Casalino LP, et al. General internists’ views on pay-for-performance and public reporting of quality scores: a national survey. Health Aff. 2007;26(2):492–9.

Werner RM, Asch DA. The unintended consequences of publicly reporting quality information. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1239–44.

Sarfaty M, Myers RE. The effect of HEDIS measurement of colorectal cancer screening on insurance plans in Pennsylvania. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(5):277–82.

Klabunde CN, et al. Health plan policies and programs for colorectal cancer screening: a national profile. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(4):273–9.

Cartwright-Smith L. Fair process in physician performance rating systems: overview and analysis of Colorado’s Physician Designation Disclosure Act. 2009. http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/web-assets/2009/09/fair-process-in-physician-performance-rating-systems. Accessed 13 Aug 2013.

Hurley RE, Strunk BC, White JS. The puzzling popularity of the PPO. Health Aff. 2004;23(2):56–68.

Attorney General of the State of New York. Agreement concerning physician performance measurement, reporting and tiering rograms; October 2007. http://healthcaredisclosure.org/docs/files/NYAG-CIGNASettlement.pdf. Accessed 12 Aug 2013.

Adams JL, et al. Physician cost profiling—reliability and risk of misclassification. New Engl J Med. 2010;362(11):1014–21.

Physician Quality Reporting System and Electronic Prescribing (eRx) Incentive Program. 2011. Reporting Experience, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

ASGE Advocacy Newsletter. http://www.asge.org/advocacy/advocacy.aspx?id=16649. Accessed 14 Aug 2013.

Lieberman DA, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(3):844–57.

National Quality Forum. NQF endorses gastrointestinal measures. Washington, DC; 2013. http://www.qualityforum.org/News_And_Resources/Press_Releases/2013/NQF_Endorses_Gastrointestinal_Measures.aspx. Accessed 17 Sept 2014.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Technical expert panels: welcome to the quality measures call for technical expert panel members page; 2014. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/TechnicalExpertPanels.html. Accessed 17 Sept 2014.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Report to Congress: Medicare Ambulatory Surgical Center Value-Based Purchasing Implementation Plan. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ASCPayment/index.html?redirect=/ascpayment/. Accessed 2 Sept 2013.

United Healthcare. UnitedHealth premium physician designation program: detailed methodlogy; 2014. https://www.unitedhealthcareonline.com/ccmcontent/ProviderII/UHC/en-US/Assets/ProviderStaticFiles/ProviderStaticFilesPdf/Unitedhealth%20Premium/Detailed_Methodology_2013–2014.pdf. Accessed 17 Sept 2014.

Medica. Premium Designation Program. https://member.medica.com/C0/PremiumDesignation/default.aspx. Accessed 15 Aug 2013.

Aetna. Understanding Aexcel; 2009. www.aetna.com/docfind/pdf/aexcel_understanding.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2013.

Cigna. Cigna care designation and physician quality and cost-efficiency displays 2013 methodologies whitepaper; 2013. http://cigna.benefitnation.net/cigna/CCN.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2013.

Chernew ME, et al. Private-payer innovation in Massachusetts: the ‘alternative quality contract’. Health Aff. 2011;30(1):51–61.

BlueCross BlueShield of North Carolina. Tiered network product; 2013. http://www.bcbsnc.com/content/providers/quality-based-networks/tiered-network.htm. Accessed 15 Aug 2013.

Lamb GC, et al. Publicly reported quality-of-care measures influenced Wisconsin Physician Groups to improve performance. Health Aff. 2013;32(3):536–43.

Long M, et al. Colorectal cancer testing in the National Veterans Health Administration. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(2):288–93.

Gellad ZF, et al. Time from positive screening fecal occult blood test to colonoscopy and risk of neoplasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(11):2497–502.

Personal communication with Jason Dominitz, MD MHS, National Program Director for Gastroenterology, Department of Veterans Affairs, August 2013.

Levin TR, et al. Organized colorectal cancer screening in integrated health care systems. Epidemiol Rev. 2011;33(1):101–10.

Levin TR. Organized cancer screening in a U.S. healthcare setting: what works. In: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Public Health Grand Rounds. 2013.

Personal communication with Doug Corley, MD PhD, Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, July 2013.

McGlynn EA. Six challenges in measuring the quality of health care. Health Aff. 1997;16(3):7–21.

Walter LC, et al. Pitfalls of converting practice guidelines into quality measures: lessons learned from a VA performance measure. JAMA. 2004;291(20):2466–70.

Kaminski MF, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(19):1795–1803.

Gellad ZF, et al. Colonoscopy withdrawal time and risk of neoplasia at 5 years: results from VA Cooperative Studies Program 380. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(8):1746–52.

Kesselheim AS, Ferris TG, Studdert DM. WIll physician-level measures of clinical performance be used in medical malpractice litigation? JAMA. 2006;295(15):1831–4.

Inadomi JM. Why you should care about screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. New Engl J Med. 2012;366(25):2421–2.

Greene SM, Reid RJ, Larson EB. Implementing the learning health system: from concept to action. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(3):207–10.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gellad, Z., Brill, J. (2015). Toward a Learning Health-Care System: Use of Colorectal Cancer Quality Measures for Physician Evaluation. In: Shaukat, A., Allen, J. (eds) Colorectal Cancer Screening. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2333-5_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2333-5_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4939-2332-8

Online ISBN: 978-1-4939-2333-5

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)