Abstract

Increasingly, organizations need people who can perform work comfortably and effectively in different countries and with people from diverse cultures. Those that possess certain cross-cultural competencies (self-management, managing relationships and teams, and managing business decisions) and immutable personality traits (extraversion, openness, and emotional stability) are more likely to be effective in these global environments. In this chapter, the authors argue that participation in global teams can help develop employees’ cross-cultural competencies. However, in order to be effective developmentally, the teams should represent a stretch challenge, they must include meaningful peer-level collaboration with team members from different cultures, and they should provide opportunities to receive feedback and support. In order to create teams that facilitate the development of cross-cultural competencies, the authors make several recommendations. First, organizations should provide a nonthreatening way for team members to learn about the cultural differences within the team, such as a face-to-face cross-cultural training session. Second, team members should collectively decide how they will manage those differences, ideally in a manner that is equally (un)comfortable for all team members. Finally, team leaders should provide clarity and coaching on process and outcomes of the teams, and they should also ensure the highest level of psychological safety is offered to all team members.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Global teams

- Cross-cultural competencies

- Immutable personality traits

- Self-management

- Organizational culture and climate

- Cultural agility

Developing employees’ cross-cultural competencies is critical for multinational companies’ (MNCs) success given that there is a current dearth of globally competent business professionals, and this talent shortage is negatively affecting organizations’ ability to compete globally and execute their plans for strategic growth. Global CEOs from more than fifty countries named their associates ability to manage within diverse cultures as one of the top concerns threatening the competitive success of their organizations (PriceWaterhouseCoopers, 2007). This has led to a talent development need: “Addressing the global-leadership gap must be an urgent priority for companies expanding their geographic reach” (Ghemawat, 2012, p. 10). Specifically, organizations need more people in their organizations who can effectively manage the complexity of foreign environments, negotiate cultural challenges, and who understand potentially conflicting regulatory requirements and stakeholder demands in foreign countries (PriceWaterhouseCoopers, 2007). Success in these tasks requires managers and business leaders to possess cross-cultural competencies and organizations are actively designing developmental opportunities to efficiently build cross-cultural competencies into the workforce. For the purpose of this chapter, we are focusing on one such initiative: participation in global teams. When designed well, participation in global teams is a developmental opportunity (DeRue & Wellman, 2009; McCauley, Ruderman, Ohlott, & Morrow, 1994) that can help facilitate the development of cross-cultural competencies.

The use of global teams is ever present in contemporary MNCs. With advances in collaborative technologies and a greater need to source talent from around the world, geographically distributed or global teams have become commonplace in organizations operating globally. Global teams are characterized by two or more members located in more than two countries. The team members share common goals and must depend on each other to accomplish them (Ilgen, 1999). Meta-analyses have demonstrated that global teams can increase creativity, thus increasing the exchange of diverse ideas and information and creating more novel decisions and solutions (Stahl, Maznevski, Voight, & Jonsen, 2010). At the individual level, global teams can also be highly developmental, helping team members build their professional networks and develop their cross-cultural competencies so critical for global leadership activities. This chapter will focus on how these cross-cultural competencies can be developed through the participation in global teams. We begin this chapter by first defining three major categories of cross-cultural competencies and describing the way in which these competencies are developed. Namely, we will discuss how attributes of the individual team members and the attributes of the developmental experience can affect the development of team members’ cross-cultural competencies. The chapter concludes with the specific features of the global teams that, when present, should enhance the development of cross-cultural competencies among team members.

Cross-Cultural Competencies Defined

Research on those who work in a cross-cultural context, such as members of global teams in multinational corporations, suggests that individuals who are effective in cross-cultural settings share certain cross-cultural competencies enabling them to demonstrate good personal adjustment in multicultural situations, to foster interpersonal relationships with people who are culturally diverse, and to effectively accomplish goals in international and multicultural settings (Thomas et al., 2008). Thus, cross-cultural competencies enable professionals to perform well and have greater ease on job tasks performed internationally and interculturally, enable professionals to work comfortably and effectively in different countries and with people from diverse cultures. Bird (2013) identified over 160 cross-cultural competencies and organized them into three primary categories: self-management, managing relationships and teams, and managing business decisions. While a review of 160 competencies is beyond the scope of this chapter (and the conceptual overlap among them is high), we can consider the broad definition of each category and the sample cross-cultural competencies within each of the categories.

Self-Management. The first set of cross-cultural competencies organizations hope to develop through the participation in global teams (and other experiential opportunities) is in the category of self-management or the ability to manage one’s own emotional and cognitive responses within the ambiguity of a cross-cultural context. Positively affecting individuals’ psychological ease in cross-cultural settings, cross-cultural competencies such as tolerance of ambiguity and appropriate self-efficacy enable individuals to maintain their composure and adjust to the ambiguity of working in multicultural and intercultural environments (Bird, Mendenhall, Stevens, & Oddou, 2010; Caligiuri, 2012). Global professionals with a higher tolerance of ambiguity are more comfortable in situations that are unfamiliar or when people or cues cannot be readily understood or familiar cues are lacking. Having an appropriate self-efficacy enables global professionals to respond to those from different cultures with greater humility and lower ethnocentrism. Those with appropriate self-efficacy may not fully understand a new situation or culture but they possess the confidence that—in time—they can learn to operate effectively and in a culturally appropriate manner in the new environment.

The need for self-management to facilitate psychological ease in cross-cultural situations is especially apparent in the international context. This need is particularly strong in expatriates, those who are living and working internationally. Research has found that expatriates experience significant and negative physiological changes in their stress hormones, including increases in prolactin levels and decreases in testosterone levels when compared to individuals who are living in their home countries (Anderzen & Arnetz, 1999). Cross-cultural competencies such as tolerance of ambiguity and self-efficacy enable global team members, expatriates, short-term assignees, and others in culturally diverse environments to work effectively in different cultures and with people from different cultures. These competencies help mitigate this stress caused by the ambiguity of the foreign environment, help individuals become better adjusted, and manage their emotional and cognitive responses through more effective emotional recognition and regulation (Matsumoto et al., 2001, 2003; Yoo, Matsumoto, & LeRoux, 2006).

Managing Relationships. Moving beyond oneself, success in international and multicultural activities requires individuals to successfully foster relationships with coworkers, clients, teammates, and others who are culturally different from themselves. Effective relationship management is particularly important for individuals who work in global teams because individuals are embedded in a multicultural setting with people from different countries who do not necessarily have direct face-to-face contact with one another. The cultural diversity, coupled with the distance, requires a greater need for trust, collaboration, and coordination among team members. The cross-cultural competencies affecting cross-cultural interactions and relationships include perspective taking and valuing diversity. Perspective taking enables individuals to understand as valid, but not necessarily agree with, the attitudes, motivations, and values of others that are potentially different and possibly opposite from their own. Those who value diversity would take those same differences and believe that there is something to be gained from the variation in individuals’ perspectives. These cross-cultural competencies positively affect individuals’ multicultural and intercultural interactions and their ability to build strong dyadic relationships with people from different cultures (Bird et al., 2010; Caligiuri, 2012).

These relationship-oriented competencies were found to be particularly important across a variety of international and multicultural contexts. Among expatriates, for example, those who are people oriented were more successful and better adjusted to working internationally (Black, 1988; Caligiuri, 2000a, 2000b; Shaffer, Harrison, Gregersen, Black, & Ferzandi, 2006). In a military context, researchers found that relationship-oriented cross-cultural competencies such as rapport building and perspective taking differentiated cross-culturally effective soldiers from those who are less effective by enabling individuals to develop relationships in different cultures and with people from different cultures (McCloskey, Behymer, Papautsky, Ross, & Abbe, 2010).

Managing Business Decisions. Another set of cross-cultural competencies are those affecting the business decisions individuals make in international and multicultural contexts. These cross-cultural competencies include willingness to adopt diverse ideas, ability to think outside the box, and operate with a deep understanding of international business. Individuals working with people from different cultures, such as those who work in global teams, need these competencies to integrate a wide range of dynamic factors from the organization and its subsidiaries, various members’ perspectives, and the like. Collectively these cross-cultural competencies suggest a high level of cognitive complexity, which enables global professionals to understand and integrate broader bases of knowledge, and balance the demands of global integration with local responsiveness (Levy, Beechler, Taylor, & Boyacigiller, 2007). In the team context, these cross-cultural competencies enable global team members to work more effectively because they facilitate an enterprise-wide or project-based mind-set over a more narrow and local perspective (Bird et al., 2010; Caligiuri, 2012).

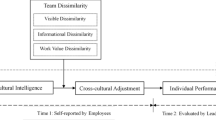

Developing Cross-Cultural Competencies

In this section of the chapter we will discuss each of the three factors affecting who will develop their cross-cultural competencies. First, we will discuss how certain people are able to more readily build their proficiency in cross-cultural competencies when they already possess the more basic immutable personality characteristics comprising cross-cultural competencies. Second, we will highlight how global teams can be designed with developmental properties to facilitate the greatest possible development of team members’ cross-cultural competencies. Lastly, we discuss the organizational climate in which the global teams operate and how leaders’ actions and priorities (i.e., their own behaviors and what they recognize and reward in others’) will affect the team members’ development of cross-cultural competencies.

Personality Characteristics to Foster the Development of Cross-Cultural Competencies

The challenge of developing cross-cultural competencies is embedded in the fact that each competency—and not just cross-cultural competencies—is composed of knowledge, skills, abilities, and other individual characteristics (KSAOs) and these KSAOs range on the extent to which they can develop and change. For competencies which are more knowledge based, at one extreme, training might suffice to promote development of the competencies. At the other extreme, competencies which are more personality based, the probability of those changing exclusively through training is comparatively low. This is particularly noteworthy because each cross-cultural competency we have studied, namely, cultural flexibility, cultural humility, and tolerance of ambiguity, have a significant element of personality in their composition (Caligiuri & Tarique, 2009, 2012).

There are three personality traits that can directly affect success in multicultural activities, such as working on international assignments and with teammates from different cultures. They are extraversion, openness, and emotional stability (Caligiuri & Tarique, 2009, 2012; Leiba-O’Sullivan, 1999; Shaffer et al., 2006). Let’s consider each, in turn. Individuals who are higher in extraversion are comfortable in social settings and seek to form interpersonal relationships with colleagues from different cultures. Extroverts tend to effectively integrate various social cultures when collaborating with others from diverse cultures (Caligiuri & Tarique, 2009, 2012; Leiba-O’Sullivan, 1999; Shaffer et al., 2006). Individuals higher in openness are more likely to be receptive to and interested in integrating new and different ways of doing things and are more likely to be comfortable with the uncertainty inherent in cross-cultural situations when social cues are not fully understood (Caligiuri & Tarique, 2009, 2012; Leiba-O’Sullivan, 1999; Shaffer et al., 2006). Likewise, emotional stability increases individuals’ psychological comfort when working with others from different cultures (Caligiuri & Tarique, 2009, 2012; Leiba-O’Sullivan, 1999; Shaffer et al., 2006).

While currently understood as predictors of success in multicultural environments, we believe that these same personality traits can also directly affect the acquisition of cross-cultural competencies. To illustrate this let’s consider the example of “tolerance of ambiguity,” the ability to manage ambiguous, new, different, and unpredictable situations. Individuals with a greater level of tolerance for ambiguity are more likely to effectively manage the stress of uncertain environments and to be more adaptive and receptive to change (Judge, Thoresen, Pucik, & Welbourne, 1999). Tolerance of ambiguity, as a competency, is partially comprised of the personality characteristic emotional stability (Caligiuri & Tarique, 2009, 2012). Tolerance of ambiguity, however, is not exclusively personality based. It is also comprised of cultural understanding which is rooted in knowledge—and more likely to be gained through training and traditional developmental opportunities. Taken together, some portion of tolerance of ambiguity could be developed through cross-cultural training, some portion of it would require deeper developmental experience, such as participation on a global team, and some portion of it would be present in those who possess emotional stability. A person with the necessary personality traits (such as emotional stability in the present example) who has been given the appropriate training and developmental opportunities would be the most likely to gain this cross-cultural competency.

Given that these personality characteristics may be necessary for cross-cultural competency development to occur and that personality characteristics are not likely going to change from the typical training and development methods, we recommend the following:

-

1.

If possible, select team members for cross-cultural competencies and their underlying personality characteristics using validated tests, structured interviews, and assessment centers.

-

2.

When selection is not possible, use assessment of cross-cultural competencies and personality traits as the team is forming. Sharing results of the assessment will help build awareness of the team’s strengths and weaknesses and enable targeted individual and team-level interventions. Through open dialog and consideration of these differences, team members can anticipate potential problem areas and create strategies to effectively leverage the differences.

-

3.

When a team is already in place, use assessment to help team members diagnose challenges and target interventions such as cross-cultural training or coaching.

The Developmental Properties of Cross-Cultural Experiences

Participation in a global team could be considered a cross-cultural experiential opportunity. Cross-cultural experiential opportunities are any work experiences occurring in an international or multicultural global work context (Dragoni et al., 2012) that vary in terms of the duration, type, and developmental properties (Caligiuri & Dragoni, in press). Like muscles being trained through physical exercise, research has shown that cross-cultural experiential opportunities can build cross-cultural competencies by leveraging participants’ existing cross-cultural competencies and knowledge absorption abilities, such as valuing different cultures, building relationships, listening and observing, coping with ambiguity, managing others, translating complex ideas, and taking action (Kayes, Kayes, & Yamazaki, 2005).

To extract developmental value from participation in global teams, it is important to understand the way in which cross-cultural experiences lead to the development of cross-cultural competencies through opportunities to work with colleagues from different cultures. Two theories provide the theoretical basis for understanding how the development of cross-cultural competencies can occur through global teams as team members interact with fellow team members from different cultures in significant, peer-level experiences. They are social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) and the contact hypothesis (Allport, 1954).

Social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) proposes that individuals learn and develop by engaging with their surroundings and the people therein. Applied to the development of cross-cultural competencies, learning occurs when team members can practice their newly learned behaviors in the intercultural or multicultural context, when they can receive feedback (e.g., from fellow team members or team leaders), and when the environment is professionally, psychologically, and emotionally safe to take risks, act authentically, and possibly make a mistake (Caligiuri & Tarique, 2009; Maznewski & DiStefano, 2000). Across developmental opportunities, access to feedback is critical when managers are engaged in challenging stretch assignments, such as participation in a global team (DeRue & Wellman, 2009).

From the perspective of development, the principles of the contact hypothesis lead to the same conclusion as the application of social learning theory—that high contact is critical for the development of cross-cultural competencies. The contact hypothesis suggests that the more peer-level interaction people have with others from a given cultural group, the more positive their attitudes will be toward people from that culture (Amir, 1969). However, merely having contact with individuals from another culture is not enough. The contact experiences should offer meaningful peer-level interactions, opportunities to work together toward a common goal, and an environment that supports the interactions (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006).

Taken together and applied to participation in global teams, social learning theory and the contact hypothesis suggest that participation in global teams can be developmental when structured with an eye toward development. We recommend:

-

1.

At the onset of the team formation, allow team members to engage in significant and meaningful interactions with fellow team members from different cultures to learn more about each other’s culture and build trust. At this early stage, however, team members may not spontaneously or proactively probe for better understanding of cultural differences. For example, they may view such questions as too personal and therefore off limits or they simply may not be thinking in terms of cultural differences (particularly individuals who have limited experience in multicultural situations). If this is the case, a team leader or team member with strong facilitation skills can help set the stage by broaching the topic and making others feel safe to have such discussions.

-

2.

While the team is working together, create a team-level mechanism to capture and disseminate knowledge such that each team member can identify, learn, and apply various approaches gleaned from their fellow team members.

-

3.

Allow teams the time to consciously develop their own team-level social norms which integrate the multiple cultural norms and behaviors from the team members. Reflection on the group norms relative to the individual norms will help members appreciate which members are being asked to stretch their own cultural norms on behalf of the group.

-

4.

Connecting this with the previous section, select team members for personality traits to accelerate the development of cross-cultural competencies during the participation in the global team by encouraging a greater number of meaningful interactions and facilitating greater openness and willingness to try new ways of collaborating.

Organizational Climate to Support the Development of Cross-Cultural Competencies

The two previous sections introduced the idea that the “right” person, when given the right cross-cultural development experience, would develop cross-cultural competencies. These practices, however, do not happen in a vacuum and apart from the organization’s overarching norms and values (i.e., its “organizational” culture) and specific workgroup climate. Organizational culture and climate can facilitate development of cross-cultural competencies when leaders, supervisors, and work units reinforce the importance of these competencies and support the overarching goal of their development with necessary resources, training, and the like. For example, team leaders can take the time to work through the cultural differences in communication and collaboration and to encourage a shared identity for the members of the global team. They can also demonstrate commitment to cross-cultural collaboration by investing in ways to facilitate collaboration with colleagues around the world or by investing in some trust-building face-time opportunities. Senior leaders can reinforce the importance of cross-cultural teamwork by investing time and resources (new technology, cross-cultural training, etc.) to facilitate global work and by communicating the importance of international and cross-cultural collaboration. Above all, the team leaders can be a source of critical feedback to team members, especially important for competency development from the more challenging global teams (DeRue & Wellman, 2009).

To identify the specific factors of organizational climate which affects the development of cross-cultural competencies, we conducted a global study of over 1,200 professionals using the Cultural Agility Climate Index (CACI; Lundby & Caligiuri, 2013a, 2013b). This index examined five dimensions of the climate to foster cross-cultural competencies: three dimensions of the CACI are people related, including work unit colleagues, direct supervisors, and organization leaders. The fourth dimension is the organization’s effectiveness in providing the necessary tools and training to facilitate global work. The fifth dimension is the organization’s overall global competitiveness, as rated by the global employees themselves. Relative weights analysis (Lundby & Johnson, 2006) revealed that senior leaders are the most important factor in promoting the perception of global effectiveness. Specifically, we found that employees need to have confidence in their senior leaders’ abilities to lead globally, perceive that their leaders are open to diverse ways of thinking and behaving, and perceive their leaders to demonstrate the importance of globalization. The second most important factor for promoting a perception of global effectiveness among employees had to do with tools and training. Specifically, when employees felt that they had the necessary tools and cross-cultural training, they were significantly more positive about the global capabilities of their organization. Together, these suggest that global team leaders have an important role to ensure the team members understand the importance of cross-cultural competence and also to ensure that the team members have the tools and training necessary to collaborate and communicate effectively.

The findings from our climate study suggest a series of practical recommendations to increase the extent to which global teams will foster the development of cross-cultural competencies:

-

1.

Organization and team leaders should establish the clear imperative for cross-cultural competencies by communicating the strategic need for such competencies in the long-term goals of the firm and provide a vision for the team’s global reach. Through reward and recognition, organizations can hold the individual leaders accountable for fostering a climate that supports the development of cross-cultural competencies.

-

2.

Teams should be provided with the collaboration tools, cross-cultural training, and other resources to work across cultures and geographies. The visible investment will reinforce the importance of effectively working across cultures and with people from different cultures in the organization.

-

3.

The organization’s climate should be monitored with a survey specifically focusing on the development of cross-cultural competencies (e.g., CACI). These surveys will identify where there may be gaps and where targeted interventions may be warranted. Progress over time can be monitored via pulse surveys to identify the interventions that have been particularly effective.

Developing Cross-Cultural Competencies Through Global Teams

Based on the backdrop for the development of cross-cultural competencies, global teams should have, at minimum, three key features: (1) participating in a global team should be a stretch challenge—an opportunity to apply one’s knowledge, skills, and abilities in different cultural contexts and with colleagues from different cultures, (2) participating in a global team should include meaningful peer-level collaborations with team members from different cultures, and (3) participating in a global team should provide opportunities to receive feedback and support for team functioning and collaboration. Taken together, teams should be constructed with these three development principles in mind. Let’s consider each more closely.

Cultural Stretch Challenges in Global Teams

In leadership development, stretch challenges for developmental purposes share certain features. For example, challenges where leaders are able to work across boundaries, have new and unfamiliar responsibilities, have a high level of responsibility, and are placed in a situation where they are creating change and managing diversity are especially developmental for building end-state competencies (DeRue & Wellman, 2009; Dragoni, Tesluk, Russell, & Oh, 2009; McCauley et al., 1994). In a parallel comparison with the experience of participating in a global team, a stretch challenge would be a developmental opportunity to apply one’s knowledge, skills, and abilities in different cultural contexts and with team members who are from different cultures (i.e., when team members are working with other members whose norms, attitudes, and values might differ from one’s own) and with a team working on a challenging and meaningful project. In the same way that individuals need to exercise a muscle in order to build strength and stamina, team members need to use their cross-cultural competencies, such as perspective taking and valuing diversity, in order to build higher levels of those cross-cultural competencies. The cultural stretch challenge needs to be somewhat beyond the team members’ comfort level. For example, if team members were all from Anglo cultures and, as individuals, did not vary in their cultural norms, attitudes, and values, then the opportunity for a cultural stretch would be limited. At the same time, if the team project provided no real challenge to any of the team members, the need to collaborate and share resources might be diminished.

Assuming the project is meaningful, participation in global teams has the potential to be a significant developmental opportunity because there are many cross-cultural differences that are manifest in global teamwork. It is in these experiences that individual team members might sense and feel differences in norms, attitudes, and values. Through the active understanding of these differences, cross-cultural competencies can be built. For example, team members’ trust can be affected (positively or negatively) by a variety of cultural differences, such as members’ tendency to trust those with whom they have a closer interpersonal relationship compared to others who might have the tendency to trust those with the best technical skills. Development occurs as team members are first able to acknowledge that they differ on a given dimension (such as the way they establish trust) and then use a wider variety of mechanisms to address the differences. In the case of building trust, a global team can use both social interactions (for the relationship-oriented members) and knowledge sharing (for the task-oriented members). Development occurs as the team members recognize the difference and change behaviors to accommodate the multiple perspectives. Thus, relationship-oriented members recognize the need to share their technical knowledge and skills while task-oriented members invest the time in building relationships.

Cross-cultural differences might also be manifest in the way team members communicate with each other. American anthropologist Hall (1976) described that in cultures where communication is high context, it is difficult to understand the meaning of what was said unless team members understand the contextual and cultural nuances around which the words were spoken (e.g., tone of voice, facial expressions, body language). High-context communicators are most comfortable among those from the same culture who can readily interpret what is said as well as what is not said. In other words, with those who have common experiences and a similar lens for interpreting meaning. Communication in these high context cultures, such as Asia, the Middle East, Latin Europe, and Latin America, is subtle and nuanced, and may seem difficult to interpret to an outsider. In cultures with a direct or low context communication style, as in the Anglo, Germanic, or Scandinavian cultures, whatever is said is meant, with little need for interpretation. In these cultures, team members observe more direct feedback being given and shorter written communications (e.g., e-mail and instant/text messages).

This cultural difference between indirect and direct communicators can be one of the more challenging aspects for global team members to work through and, therefore, has the greatest opportunity for development when addressed. As with the previous example, team members would need to first be able to understand the variance within their team on the preference for direct versus indirect communications. Then they would need to exercise their cross-cultural competencies and learn to interpret communications through a different lens. Team members from high context communication cultures would need to practice interpreting only the direct meaning of a communiqué and ask for clarity on interpretations offered beyond the direct communication. At the same time, team members from low context cultures will need to consider more nuanced meaning to the context of communication and then test their understanding of the intended message. In both cases, global team members are building their repertoire of cultural understandings.

Another way global teams can be developmental is through the way they manage their team functioning. For example, deadlines and deliverables are needed in global teams but the team members might also differ on how they view time. Some team members might believe that time should be strictly monitored and controlled, treating time as a commodity to be bought, spent, and wasted. Other team members might view time more fluidly, placing a greater emphasis on how work is accomplished, as opposed to meeting and keeping deadlines. Team members also differ on the extent to which they are collective oriented or individual oriented. In the highly collectivist cultures there is a strong group orientation or a desire to maintain harmony. In the more individualist cultures one’s personal goals would supersede the collective goals. In cultures valuing the group’s interest, being a member of a successful team is highly rewarding. In societies valuing the individuals’ interests, people expect to be personally rewarded and recognized for their unique contributions. The value of a team—and what it means to be a part of it—will vary greatly depending on a society’s orientation on this dimension. In these cultural examples, the participation in global teams can be developmental because team members would need to first acknowledge that differences exist and then reconcile how they as a team will interpret deadlines, acknowledge individual contribution, communicate with one another, and the like. Both understanding of differences and the subsequent creation of team norms enable team members to stretch and grow their cross-cultural competencies.

As the previous paragraphs suggest, the act of identifying cultural differences is not, on its own, developmental. Development occurs when team members have the opportunity to integrate the cultural differences of the members and come to agreement on how they will operate in the future. In addition to being developmental, research has found that these multicultural teams functioned better over time when they had created a hybrid team culture—their own team-level norms for interactions, communications, goal setting, and the like (Earley & Mosakowski, 2000). Based on this research, Earley and Mosakowski (2000) advise that teams should work to create their own rules for interpersonal and task-related interactions, performance expectations, communication, and conflict management. In working through the team members’ cultural differences to create team norms and a team identity, development of cross-cultural competencies can occur.

Peer-Level Collaboration Among Global Team Members

The idea of peer-level collaboration seems the most straightforward of the factors affecting development of cross-cultural competencies from global teams. With the tremendous amount of communication, conferencing, and collaborative technology available for interactions of geographically distributed teams, the possibility of having meaningful peer-level collaborations among team members should be high. However, when multicultural team members are not colocated at any point in their team’s life-cycle, their ability to establish trust and rapport, and to have meaningful ongoing interactions can be diminished.

The issue at hand is whether technology will limit the potential for development. The use of project management and knowledge management systems to facilitate the mechanics of geographically distributed global teams is pervasive. When almost 4,000 managers from all around the world were surveyed on their organizations’ use of unified communications and collaboration technology, nearly 40 % of them reported that their organizations will increase spending on these tools. Of the organizations that have not yet deployed communication and collaboration tools, more than 80 % plan to deploy them in the next 2–3 years. While the use of project management and knowledge management systems can help facilitate the mechanics of geographically distributed global teams, their use might obfuscate the need for meaningful in-person interactions.

Technology can, of course, reduce travel costs, improve the speed of collaboration among geographically dispersed team members, and can create a virtual meeting space where the team’s work can be done. With a focus on development of cross-cultural competencies, however, the limits of their use should be understood. Gibson and Gibbs (2006) found that the greater the cross-national teams’ reliance on electronic communications, the less innovative they were. Interpersonal relationships, and not technology, yielded the most innovative results of these global teams. The teams which had created a psychologically safe communication climate were the ones with the highest product innovation. Specifically, among those teams with a high use of electronic communications, having a psychologically safe communication climate produced a roughly 20 % increase in the project teams’ innovation ratings over those in a climate the members did not consider psychologically safe. In a psychologically safe climate, team members trusted each other and believed they could express their ideas, talk through the problems they encountered, and be assertive about their thoughts and feelings. Building trust and having comfortable methods for meaningful interactions and collaboration enabled these global professionals to succeed—and develop—collectively.

Using collaborative technology does not fully vanquish cultural differences any more than the use of English as a common business language does. When people use communication and collaboration technology, they still bring to the virtual table their cultural norms for sharing of information, for communicating with peers, their preferences for collaboration, and their preferences for technology. In other words, technology can help bring people together virtually but it does not strip away the cultural nuances that are deeply ingrained in every individual. This was evident in a study conducted by Shachaf (2008) in which geographically distributed, technology-laden team members’ cultural and language differences resulted in miscommunication, which, in turn, negatively affected trust, cohesion, and team identity. It would be difficult to create psychologically safe communications with colleagues from different countries when the basic elements of trust and cohesion are missing.

Peer-level collaboration of team members is fundamental for the development of cross-cultural competencies. The interactions involved in creating psychologically safe team communications, trust, and cohesion with team members from different cultures have the potential to be a highly developmental process; members would learn the pressure points or places where they need to be sensitive to each other’s differences, they would learn to accommodate each other, and to integrate their preferences in a comfortable way for team members to collaborate effectively.

Feedback and Support for Global Team Functioning

The last feature of global teams that would make them particularly developmental is through the feedback and support function. Organizations can facilitate the developmental properties of global teams by providing strong team leadership and the resources needed to create trust and cohesion. Global team leaders can encourage sensitivity to those issues directly related to the cultural differences and encourage the creation of team-level ground rules. Global team leaders can work to break-up or prevent members’ natural tendencies to favor those from their own culture (Earley & Mosakowski, 2000; Gibbs, 2006; Gibson & Vermeulen, 2003). Global team leaders can also be the cultural guides to help the team members create their own team-level norms and identity and also help facilitate credibility and trust building.

Team leaders can assist with the process of the team to balance the influence, rewards, and workload among team members to ensure that all members are treated fairly. They can provide team-level ground rules that apply equally to and are reinforced among all members on tangible aspects of team processes, such as frequency of emails, expectations for communications, and the like. The global team leaders can also create ways to increase information flows through interactions by making some team members “boundary spanners,” especially in circumstances when face-to-face interaction among all members is not possible. Research found that information within global teams flow through a few boundary spanning individuals (Joshi, LaBianca, & Caligiuri, 2002). These boundary spanning team members are central to the team’s network for the flow of both information and trust. Often better traveled than other members and with a broader network, boundary spanning team members would likely also experience the greatest developmental gains from their participation in the global team.

Team leaders can also be integral in facilitating cross-cultural competency development of the team members. Global team leaders can proactively address issues potentially exacerbated by cross-cultural differences among team members. For example, cultures will vary in their patterns of speaking and listening—especially the use of silence; how this will affect conference calls and what ground rule will be established to address it, is the type of issue a team leader could address. Global team leaders can play the role of cultural coach by providing individual members with feedback on the way their behaviors might be interpreted through the eyes of other members—and how they can shape their behaviors in the future. In this sense, they can also proactively anticipate conflict and miscommunications and mentor members to help them build their perspective taking of other members. These global team leaders will be in a position to monitor team members’ competency development.

Recommendations

Based on the three key features to facilitate development through participation in global teams (a cultural stretch challenge, peer-level collaborations, and feedback and support), we make the following recommendations:

-

1.

Organizations should provide a nonthreatening way for team members to learn about the cultural differences within the team, such as a face-to-face cross-cultural training session. The discussion should be facilitated such that team members can have an open discussion of the differences and similarities among team members. This training should allow team members to understand, without judgment, the ways in which members might differ and how those cultural differences could affect the team’s effectiveness.

-

2.

As a group, team members should collectively decide how they will manage those differences, ideally in a manner that is equally (un)comfortable for all team members. This activity should be facilitated by someone who understands the various cultural styles and can anticipate resistance as the team (with varying levels of members’ cross-cultural competencies) work through their differences.

-

3.

Team leaders should understand their role in facilitating cross-cultural competency development. Once team processes have been established, team leaders can provide clarity and coaching on process and outcomes of the teams, such as reinforcing deadlines and deliverables. Team leaders can also ensure the highest level of psychological safety is offered to all team members by reinforcing behaviors—even virtually—that adhere to development-enhancing climate.

Conclusion

Developing employees’ cross-cultural competencies is critical for MNCs’ success. Global CEOs echo this sentiment, indicating that inability to work effectively in a global environment is a serious impediment to their future success. Key to overcoming this challenge are teams of employees who can manage in foreign environments, negotiate cultural challenges (with one another as well as with other teams), and adapt to new and unfamiliar situations. Success in these tasks requires cross-cultural competencies and as we have argued in this chapter, when designed well, global teams can help facilitate the development of cross-cultural competencies.

The cross-cultural competencies that research and practical experience suggest are particularly important include self-management (ability to manage one’s own emotions and behaviors in ambiguous situations), relationship management (creating and sustaining positive cross-cultural relationships), and business decision management (deep understanding and appreciation of the global business context). Individuals who possess these competencies, as we have shown, are better suited to operate in a global and ambiguous environment. Once organizations recognize these key competencies for international effectiveness, they can then be systematic about assessing team members (e.g., assessing for the “right” personality traits), providing developmental opportunities (e.g., stretch assignments for teams), and creating a climate for global effectiveness.

As anyone who has traveled or worked internationally can attest, there is no one best way to anticipate and navigate all the complexities and nuances of international and cross-cultural work. However, if organizations pay attention to select individuals with the right mind-set and personality traits for successful global work, if they provide developmental opportunities to prepare teams to work effectively in a global environment, and if they create a climate that appreciates and reinforces these values, we believe that will go a long way toward resolving the concerns that were expressed by so many CEOs.

References

Allport, G. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Amir, Y. (1969). Contact hypothesis in ethnic relations. Psychological Bulletin, 71, 319–342.

Anderzen, I., & Arnetz, B. B. (1999). Psychophysiological reactions to international adjustment: results from a controlled, longitudinal study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 68, 67–75.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bird, A. (2013). Mapping the content domain of global leadership competencies. In M. E. Mendenhall, J. S. Osland, A. Bird, G. R. Oddou, M. L. Maznevski, M. J. Stevens, & G. K. Stahl (Eds.), Global leadership: Research, practice, and development (2nd ed., pp. 80–96). New York: Routledge.

Bird, A., Mendenhall, M., Stevens, M. J., & Oddou, G. (2010). Defining the content domain of intercultural competence for global leaders. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(8), 810–828.

Black, J. S. (1988). Work role transitions: A study of American expatriate managers in Japan. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(2), 277–294.

Caligiuri, P. M. (2000a). The big five personality characteristics as predictors of expatriate’s desire to terminate the assignment and supervisor-rated performance. Personnel Psychology, 53(1), 67–88.

Caligiuri, P. M. (2000b). Selecting expatriates for personality characteristics: A moderating effect of personality on the relationship between host national contact and cross-cultural adjustment. Management International Review, 40(1), 61–80.

Caligiuri, P. (2012). Cultural agility: Building a pipeline of successful global professionals. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Caligiuri, P.M., & Dragoni, L. (in press). Global leadership development. Invited chapter for D. Collings, G. Wood, & P. Caligiuri (Eds.). Companion to International Human Resource Management (Routledge).

Caligiuri, P., & Tarique, I. (2012). Dynamic cross-cultural competencies and global leadership effectiveness. Journal of World Business, 47(4), 612–622.

Caligiuri, P., & Tarique, I. (2009). Predicting effectiveness in global leadership activities. Journal of World Business, 44, 336–346.

DeRue, S. D., & Wellman, N. (2009). Developing leaders via experience: The role of developmental challenge, learning orientation, and feedback availability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(4), 859–875.

Dragoni, L., Oh, I.-S., Moore, O., Vankatwyk, P., Hazucha, J., & Tesluk, P. (2012). Global work experience: Does it make leaders more effective? Wharton Conference, University of Pennsylvania.

Dragoni, L., Tesluk, P. E., Russell, J. E., & Oh, I.-S. (2009). Understanding managerial development: integrating developmental assignments, learning orientation, and access to developmental opportunities in predicting managerial competencies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 52(4), 731–743.

Earley, P. C., & Mosakowski, E. (2000). Creating hybrid team cultures: An empirical test of transnational team functioning. Academy of Management Journal, 43(1), 26–49.

Ghemawat, P. (2012). Developing global leaders. McKinsey Quarterly, pp. 1–10.

Gibbs, J. L. (2006). Decoupling and coupling in global teams: Implications for human resource management. In G. K. Stahl & I. Bjorkman (Eds.), Handbook of research in international human resource management (pp. 347–363). Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Gibson, C. B., & Gibbs, J. L. (2006). Unpacking the concept of virtuality: The effects of geographic dispersion, electronic dependence, dynamic structure, and national diversity on team innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51, 451–495.

Gibson, C., & Vermeulen, F. (2003). A healthy divide: Subgroups as a stimulus for team learning behavior. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48, 202–239.

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. Garden City, NY: Anchor.

Ilgen, D. R. (1999). Teams in organizations: Some implications. American Psychologist, 54, 129–139.

Joshi, A., LaBianca, G., & Caligiuri, P. M. (2002). Getting along long distance: Understanding conflict in a multinational team through network analysis. Journal of World Business, 37(4), 277–292.

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Pucik, V., & Welbourne, T. M. (1999). Managerial coping with organizational change: A dispositional perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 107–122.

Kayes, D. C., Kayes, A. B., & Yamazaki, Y. (2005). Essential competencies for cross-cultural knowledge absorption. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 20(7), 578–589.

Leiba-O’Sullivan, S. (1999). The distinction between stable and dynamic cross-cultural competencies: Implications for expatriate trainability. Journal of International Business Studies, 30, 709–726.

Levy, O., Beechler, S., Taylor, S., & Boyacigiller, N. (2007). What we talk about when we talk about global mindset: Managerial cognition in multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 38, 231–258.

Lundby, K.M., & Caligiuri, P. (2013, February). Cultural agility climate: What organizations and their leaders need to know about functioning effectively in a global environment. Presented at 3M Corporation’s Innovation Center, Saint Paul, MN.

Lundby, K. M., & Caligiuri, P. (2013). Leveraging organizational climate to understand cultural agility and foster effective global leadership. People & Strategy, 36, 28–32.

Lundby, K. M., & Johnson, J. W. (2006). Relative weights of predictors: What is important when many forces are operating. In K. Kraut, A. H. Church, & J. Waclawksi (Eds.), Getting action from organizational surveys. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Matsumoto, D., LeRoux, J. A., Iwamoto, M., Choi, J. W., Rogers, D., Tatani, H., et al. (2003). The robustness of the intercultural adjustment potential scale (ICAPS): The search for a universal psychological engine of adjustment. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27, 543–562.

Matsumoto, D., LeRoux, J., Ratzlaff, C., Tatani, H., Uchida, H., Kim, C., et al. (2001). Development and validation of a measure of intercultural adjustment potential in Japanese sojourners: The intercultural adjustment potential scale (ICAPS). International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 25, 483–510.

Maznewski, M. L., & DiStefano, J. J. (2000). Global leaders are team players: Developing global leaders through membership on global teams. Human Resource Management, 39, 195–208.

McCauley, C. D., Ruderman, M. N., Ohlott, P. J., & Morrow, J. E. (1994). Assessing the developmental components of managerial jobs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 544–560.

McCloskey, M., Behymer, K., Papautsky, E. L., Ross, K., & Abbe, A. (2010). A developmental model of cross-cultural competence at the tactical level. Arlington, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences.

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 751–783.

PriceWaterhouseCoopers. (2007). 10th annual global CEO survey. New York: PriceWaterhouseCoopers.

Shachaf, P. (2008). Cultural diversity in information and communication technology impacts on global virtual teams: An exploratory study. Information and Management, 45, 131–142.

Shaffer, M. A., Harrison, D. A., Gregersen, H., Black, J. S., & Ferzandi, L. A. (2006). You can take it with you: Individual differences and expatriate effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1), 109–125. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.109.

Stahl, G., Maznevski, M., Voight, A., & Jonsen, K. (2010). Unraveling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: A meta-analysis of research on multicultural work groups. Journal of International Business Studies, 41, 690–709.

Thomas, D. C., Elron, E., Stahl, G., Ekelund, B. Z., Ravelin, E. C., Cerdin, J.-L., et al. (2008). Cultural intelligence: Domain and assessment. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 8, 123–143.

Yoo, S. H., Matsumoto, D., & LeRoux, J. A. (2006). The influence of emotion recognition and emotion regulation on intercultural adjustment. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30, 345–363.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Caligiuri, P., Lundby, K. (2015). Developing Cross-Cultural Competencies Through Global Teams. In: Wildman, J., Griffith, R. (eds) Leading Global Teams. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2050-1_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2050-1_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4939-2049-5

Online ISBN: 978-1-4939-2050-1

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)