Abstract

In the legal system, jurors serve as a reflection of community sentiment. Jurors’ task is to “find facts” and apply the law to those facts, but in the course of doing so, they necessarily make moral judgments about how bad a crime or criminal is when they render verdicts. This process allows jurors to express their own sentiments, which are reflected in their ultimate verdict. The current chapter describes two studies that assessed some of those sentiments by examining how mock jurors perceive child sexual abuse perpetrators based on the relationship between the perpetrator and child. Legally, judgments of the perpetrator should be stable regardless of the relationship between the perpetrator and the child; however, results indicated that mock jurors may be considering the relationship between the perpetrator and the child when making decisions. The chapter also addresses the challenges and benefits of assessing community sentiment through mock juror experiments and surveys.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Under the Constitution, criminal defendants are guaranteed the right of a trial by a jury of their peers (US Const. Amend. 6). This constitutional right puts juries in the position of making decisions about applying the law to a particular case. Jurors are supposed to overcome any biases that they have and apply the “black-letter law” to the facts of the case; however, psychological research on jury decision making indicates that jurors are often unable to do so and rather apply “commonsense justice” (Finkel, 1995). Commonsense justice, according to Finkel (1995), is what ordinary people think the law should be. Thus, in many instances, jurors may be influenced by psychological factors as well as community sentiment when rendering a verdict in a case. This chapter will investigate mock jurors’ perceptions of child sexual abuse (CSA) perpetrators based on the perpetrator’s relationship with the child, while also discussing the benefits and challenges of using experimental and survey jury research to measure community sentiment.

Community Sentiment

As other chapters in the present volume describe, community sentiment is often defined as the public’s opinion on a topic. In the American legal system, jurors serve as the ultimate reflection of community sentiment. Researching juror decisions in trial simulation experiments and surveys is one way of assessing community sentiment in a way that is legally relevant.

Community Sentiment and Juries

Community sentiment can influence the jury in one of two ways. First, juries can be encouraged to use community sentiment under the law. Alternatively, jurors may intentionally or unintentionally consider community sentiment even without being explicitly required to do so.

Required Consideration of Community Sentiment. There are a limited number of circumstances in which juries are instructed to consider community sentiment when rendering decisions. One such area of law is obscenity law. Under obscenity law, jurors are supposed to determine whether the material in question offends contemporary community standards (Miller v. California, 1973). Understanding community sentiment and how jurors perceive community sentiment is important in these cases because it should be a deciding factor in the jury’s analysis of the case. In these cases, community sentiment essentially is the law.

Permitted Consideration of Community Sentiment. In most cases, juries are not instructed to apply community sentiment when making a decision (Finkel, 1995). In these cases, jurors are supposed to examine the facts of the case and apply the law objectively. However, decades of psycholegal research indicate that jurors are not very good at objectively applying the law and often extralegal factors, such as demographic characteristics of the defendant or the juror, influence juror perceptions and verdicts (see, e.g., Devine, 2012).

For example, the chapters by Miller and Chamberlain (Chap. 1), Armstrong and colleagues (Chap. 17), and Sigillo and Sicafuse (Chap. 2) discuss how the media reflect (and in some cases drive) community sentiment. One way that the media influence community sentiment toward a particular case is through pretrial publicity (PTP). Research on PTP indicates that it usually espouses negative sentiment toward the defendant (Imrich, Mullin, & Linz, 1995). Exposure to PTP also increases the likelihood that the jury will convict the defendant (Devine, 2012; Spano, Groscup, & Penrod, 2011; Steblay, Besirevic, Fulero, & Jimenez-Lorente, 1999). Consequently, when attorneys are concerned that PTP is going to result in negative sentiment toward their clients, they may request a change of venue or a delay to mitigate the effects of PTP (Kovera & Borgida, 2010; Spano et al., 2011). The concern with PTP is one indication that jurors may improperly use community sentiment when reaching a decision.

Although the law deems it undesirable in most cases for jurors to consider community sentiment in their decisions, juries legally have the right to ignore, or “nullify,” the law. Jury nullification occurs when juries deliberately render a decision that is inconsistent with the law but that they consider more fair or appropriate (Hamm, Bornstein, & Perkins, 2013; Horowitz, Kerr, & Niedermeier, 2001). Although nullification could involve the conviction of someone the jury believes is legally innocent, in most cases nullifiers acquit someone who should, under the law, be guilty. Thus, in order to be considered nullification, jurors must have the intent not to apply the law to the particular case; simply failing to convict under the standard of reasonable doubt is not sufficient (e.g., King, 1998; Leipold, 1996; Marder, 1999; Scheflin, 1972; Simson, 1976; Van Dyke, 1970).

Scholars in the legal community disagree about whether nullification should be permitted. On the one side, proponents argue that the basis of having a jury system is to have jurors serve as the conscience of the community, who can nullify the law when convicting a legally guilty individual would offend the community conscience (United States v. Spock, 1969; see also Scheflin, 1972). Alternatively, opponents argue that the legislature should represent community sentiment, and the jury has the duty of enforcing the laws enacted by the larger community (Hamm et al., 2013). Ultimately, the Supreme Court has upheld the jury’s right to nullify the law (Sparf & Hansen v. United States, 1865); however, there is no requirement to inform juries about this capacity, and courts generally refrain from doing so (Hamm et al., 2013). Thus, jurors may deliberately use community sentiment in making decisions that contradict the law, but the court usually does not inform them that they have this capability.

Estimates of the frequency of jury nullification are hard to come by, but it is almost certainly quite rare (Hamm et al., 2013). It is most likely to come up for offenses where the law is rapidly evolving, such as euthanasia or battered woman syndrome, or for offenses that touch on large social movements, such as civil rights, the military draft, or drug legalization. For more “established” offenses, such as child sexual abuse, it is less likely to be an issue. Nonetheless, community sentiment could still influence jurors’ decisions. Certain illegal behaviors, both civil and criminal, are capable of triggering jurors’ moral outrage, and that outrage can color jury decision making (e.g., Kahneman, Schkade, & Sunstein, 1998; Vidmar, 1997).

Juror Sentiment Toward CSA. One legal problem that is potentially subject to strong community sentiment is child sexual abuse (CSA). CSA is a serious problem in society (Bottoms, Golding, Stevenson, Wiley, & Yozwiak, 2007; Myers, 2008; Vieth, 2005) with over three million reports of CSA each year, one million of which are substantiated (Bottoms et al., 2007). Additionally, CSA is a topic that has garnered attention from the media. In 1992, the media focused on reports of CSA by priests, with over 400 priests being accused of sexually assaulting children, primarily young boys, between 1982 and 1992 (Berry, 1992). Between 2001 and 2005, over 2,500 teachers nationwide lost their credentials for sexually assaulting their students (Irvine & Tanner, 2007). Pennsylvania currently is attempting to pass legislation to address this problem, which they have declared is “almost an epidemic” (Hughes, 2014). And in 2011 and 2012, newspapers were filled with stories of Pennsylvania State University football coach, Jerry Sandusky, who was found guilty of sexually assaulting ten underage boys (upheld on appeal; see Pennsylvania v. Sandusky, 2013; see also, Ganim, 2011).

Beyond being a societal concern, CSA is also a major legal concern. CSA constitutes the majority of sexual assault cases in the legal system (Snyder, 2000). Because CSA cases are so prevalent in the legal system, they consume quite a bit of time and resources. For example, CSA cases constitute 10 % of child maltreatment cases (Bottoms et al., 2007) and the majority of cases in which children testify (Goodman, Quas, Bulkley, & Shapiro, 1999).

Given that CSA is a legal concern that elicits strong negative feelings from the community (as evidenced by the outrage portrayed in media), it is important to understand how juries make decisions in CSA cases. Although jurors are supposed to make decisions based only on the facts of the case, CSA cases often lack physical evidence, forcing jurors to base their decisions primarily on the testimony of the alleged victims (Bottoms et al., 2007; Myers, 1998; Pennsylvania v. Ritchie, 1987; Whitcomb, Shapiro, & Stellwagen, 1985). Although legal evidence is usually the most influential factor in jurors’ decisions (Devine, Clayton, Dunford, Seying, & Pryce, 2001), jurors in CSA cases are particularly prone to being influenced by extralegal factors that are not technically relevant to the legal decision (Bottoms et al., 2007).

Demographic characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, and age of the trial participants (jurors, victim, and defendant), influence decisions in CSA cases (see Bottoms et al., 2007, for a review). One of the most studied characteristics is gender of the people involved. Juror gender is a complicated factor which works differently in various studies (see, e.g., Schutte & Hosch, 1997, for a review); however, on average female jurors are more likely than male jurors to favor the prosecution (Allen & Nightingale, 1997; Bottoms, 1993; Isquith, Levine, & Scheiner, 1993; Kovera, Levy, Borgida, & Penrod, 1994; Orcutt et al., 2001). Although the underlying mechanism is also complicated, women perceive CSA as more serious and react more negatively (e.g., Finlayson & Koocher, 1991; Kovera, Borgida, Gresham, Swim, & Gray, 1993). On the other hand, gender of the victim does not usually influence verdict (Bottoms & Goodman, 1994; Crowley, O’Callaghan, & Ball, 1994; Isquith et al., 1993; Myers, Redlich, Goodman, Prizmich, & Imwinkelried, 1999). Although relatively little research has investigated the influence of perpetrator gender, likely under the assumption that women rarely perpetrate CSA (Bolton, Morris, & MacEachron, 1989; Bottoms et al., 2007; Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith, 1990), male defendants are perceived more negatively than female defendants (Finkelhor & Redfield, 1984; O’Donohue, Smith, & Schewe, 1998; Smith, Foromouth, & Morris, 1997). Gender of the defendant interacts with gender of the victim such that same-gender sexual abuse is perceived more negatively than opposite-gender abuse (Bornstein & Muller, 2001; Dollar, Perry, Foromouth, & Holt, 2004; Drugge, 1992; Maynard & Wiederman, 1997).

In addition to demographic characteristics, characteristics of the abuse influence juror decisions. For example, if the child delays reporting it (due to repression or not), the child’s testimony is perceived as less credible than if the child reports abuse immediately (Golding, Sego, Sanchez, & Hasemann, 1995; Golding, Sanchez, & Sego, 1997). The way the abuse is disclosed also influences decisions, such that full disclosure is perceived as more believable than partial disclosure which is followed by full disclosure (Yozwiak, Golding, & Marsil, 2004).

The relationship between the perpetrator and the victim is another characteristic of the abuse that influences jurors’ decisions (Bornstein, Kaplan, & Perry, 2007). Bornstein and colleagues (2007) found that jurors rated the abuse significantly more negatively when the perpetrator was the child’s parent than when the perpetrator was the child’s babysitter. This finding is consistent with the literature which indicates that the impact of CSA increases as the relationship between the perpetrator and the child becomes more intimate (Kendall-Tackett, Williams, & Finkelhor, 1993). However, very little research has manipulated the relationship between the perpetrator and the child (Bottoms et al., 2007), so it is not clear how perceptions of other perpetrator–victim relationships influence juror decisions.

Conducting Jury Research

As jurors are laypeople who, by definition, represent the community in judging their peers, they are an ideal vehicle for assessing community sentiment. By measuring which factors do and do not influence jury decisions, one can make inferences about how community members view certain offenses. For example, if mock jurors are more likely to convict a defendant accused of same-sex CSA than opposite-sex CSA even though the facts (apart from the parties’ gender) are the same (see Bornstein & Muller, 2001), then one might reasonably suppose that the community views same-sex CSA more harshly.

There are several techniques, some used more commonly than others, for conducting research on juries (see, e.g., Bornstein, in press). The most common methods are direct observation of jury deliberations, which, with very rare exceptions, is impermissible; case studies and/or posttrial interviews with jurors; archival analyses of (usually large) datasets of jury verdicts; experimental simulations, or mock juror/jury studies; and field studies, in which judges randomly assign juries to one of multiple experimental conditions. Importantly, all of these methods except for simulations use real jurors reaching real verdicts. Jury simulations, on the other hand, employ mock jurors who are role-playing and making hypothetical decisions without actual consequences.

The pros and cons of jury simulations have been debated extensively elsewhere (e.g., Diamond, 1997; Wiener, Krauss, & Lieberman, 2011). Although experimental simulations have significant drawbacks—most notably, they often lack “verisimilitude,” using nonrepresentative mock jurors and relatively impoverished materials, thereby raising important issues of external and ecological validity—they also offer a number of advantages (Bornstein, in press). For example, they allow for a high degree of experimental control, which confers high internal validity and permits causal inferences; they have both scientific and practical implications; and they can address both the processes involved in jury decision making (i.e., how jurors make the decisions) and the outcomes of jury decision making (i.e., what decisions they make). Community sentiment is relevant to both kinds of judgments: It can influence how jurors make decisions, as if, for example, sentiment leads them to ignore legally admissible evidence and make decisions based on prejudice (Vidmar, 1997), and, of course, it can affect the ultimate decisions themselves, as in the case of jury nullification.

Although jury simulations are, in some respects, relatively cheap and easy to run—mock trials are usually considerably shorter than real trials, and researchers often have easy access to a large pool of undergraduate research participants—they present challenges as well. Apart from designing studies that advance scientific theory or important policy questions, and ideally both, the research needs to make sense both legally and psychologically. And as with any psychological research, the measures need to be reliable, valid, and sensitive. When using legal judgments like verdicts or widely used psychological measures like attribution of responsibility, reliability is rarely an issue. However, as noted above, validity concerns bedevil even the most carefully designed jury experiments. In addition, sensitivity can require careful attention. It would be impossible to determine the effect of a variable like child–perpetrator relationship, for instance, if the simulated trial were so one-sided that nearly all of the mock jurors either convicted or acquitted the defendant.

To address this sensitivity concern, much jury simulation research proceeds in stages. Before recruiting participants to adopt the role of jurors, the trial stimuli need to be developed and pilot tested. In many cases, this involves honing the case facts over successive iterations until the trial is fairly balanced and yields an approximately even split of verdicts. In other cases, as in the studies described below, it involves asking nonlegal questions about components of a legal case. For example, we asked participants about their perception of an incident of CSA, which was not presented in the context of a trial, such as how traumatic the event was and whether the adult took advantage of his relationship with the child. Such questions are not legal judgments, per se, but they are an indication of sentiments toward the case, and those sentiments might reasonably underlie participants’ decisions in a legal case arising from the incident.

The Current Research

The goal of the current research was to understand how parties involved in an alleged CSA incident are perceived based on the relationship between the perpetrator and the child. As described above, a number of incident characteristics influence perceptions of CSA, including the relationship between the parties (Bornstein et al., 2007; Bottoms et al., 2007; Read, Connolly, & Welsh, 2006). College students’ perceptions of CSA perpetrators were assessed in the current two studies. The initial survey study was intended to assess sentiment toward child sexual abusers based on the relationship between the perpetrator and the child. The survey study measured college students’ perceptions of a general description of child sexual abuse and variations that described twelve different perpetrator–child relationships. The second study was an experimental mock juror study that expanded on the first to determine how sentiment toward child sexual abusers is reflected in juror decisions. The mock juror study provided participants with more detailed information in the form of a trial transcript about one of three different perpetrator–child relationships (described in more detail below).

Study 1: Survey of CSA Perceptions for Different Perpetrator–Child Relationships

The survey study asked participants to rate a generic description of CSA on 13 questions (e.g., truthfulness of the story, effect of the event on the child, perceptions of the alleged perpetrator, and responsibility for the event). Participants were then given a series of six variations of the perpetrator–child relationship which came from a larger set of 12 relationships (father, mother’s boyfriend, basketball coach, teacher, priest, minister, rabbi, neighbor, store owner, stranger, therapist, and doctor). We hypothesized that perpetrators who had a more intimate relationship with the child (e.g., father, mother’s boyfriend) would be perceived more negatively than perpetrators with a more distant relationship (e.g., stranger, store owner). We also hypothesized that perpetrators who were involved in religious professions (i.e., minister, priest, and rabbi) would be rated more negatively than nonreligious perpetrators.

Method. Participants in the survey study were 109 undergraduates (65 % female, M age = 19.26, 82.7 % White) who received class credit for their participation. All participants first read a generic description of a CSA incident involving inappropriate touching of a young boy by an adult male. The generic vignette read as follows:

Matthew’s grades have declined lately and he has been acting withdrawn. This is different from his usual behavior. Matthew is 13 years old. He finally confessed to his mother the details of an incident that occurred with an adult male a few weeks prior. Although Matthew did not tell his mother who the adult was, Matthew described to his mother that he was alone with the adult when the adult put his hand on Matthew’s shoulder. The adult started to rub Matthew’s back and said he was happy Matthew was there. Then the adult undid Matthew’s pants and began rubbing his penis through his underwear for what seemed to be about 10 min. After he stopped, he told Matthew not to tell anyone about what happened.

After reading the generic vignette, participants rated the description on 13 nine-point Likert-type scales. The 13 questions assessed the amount of trauma experienced by the child, the severity of the perpetrator’s actions, the believability of the child’s description, the likelihood of the event occurring generally, the likelihood the child would report the event, the degree to which the adult violated the child’s trust, the degree to which the adult should protect the well-being of a child, the extent to which the adult took advantage of his relationship with the child, the reprehensibility of the adult’s actions, the likelihood the incident constitutes sexual abuse, the severity of any punishment, and the responsibility of the child.

After rating the generic description, participants rated six more vignettes, which were identical to the generic vignette but contained additional information about the perpetrator, on the same 13 questions. Specifically, they varied in terms of the relationship of the child to the alleged perpetrator. Participants were randomly assigned to receive one of two sets of descriptions, the order of which was also random. The perpetrator–child relationships were paired between sets so that the two sets were similar and neither set was excessively redundant. The first set of descriptions included the boy’s father, teacher, minister, neighbor, doctor, or stranger; the second set of descriptions included the mother’s boyfriend, basketball coach, priest, rabbi, therapist, or a store owner. Participants then provided demographic information and were debriefed.

Results. Nine of the thirteen questions loaded on a single “seriousness” factor which had decent reliability, α = .75. This included questions regarding trauma of the event, severity, believability of the child, violation of trust, duty to protect the child, degree the perpetrator took advantage of the child, reprehensibility of the crime, the likelihood it was CSA, and the degree of punishment. Scores on the nine questions were then averaged to create a “seriousness” score. Table 4.1 provides the mean seriousness ratings for each perpetrator. In the preliminary analyses, participant gender was included as a separate factor; it had no main or interactive effects, so subsequent analyses collapse across gender.

Overall, perceptions of the event were that it was relatively serious: The lowest mean score (for the doctor) was 7.53 out of 9. This shows the overwhelmingly negative sentiment toward CSA (Vidmar, 1997), as the present incident was relatively mild when considered along the full spectrum of abuse (we do not at all mean to imply that the incident was benign, merely that a single episode of fondling through clothing might be seen as less severe than many other forms of CSA; see, e.g., Bornstein et al., 2007).

Since each participant read only one set of the descriptions (half), a series of ANOVAs and paired samples t-tests were conducted to assess whether each combination of relationships differed on the seriousness factor. As expected, perceptions of the incident and the perpetrator depended on the child’s relationship to the perpetrator, F(1, 106) = 2.02, p < 0.05, R 2 = 0.02. Consistent with the hypothesis, abuse by the father was rated more serious than all of the other perpetrators except the priest (see Table 4.1). Partially consistent with the hypothesis, abuse by the minister and the priest (religious perpetrators) was rated significantly more serious than abuse by the other perpetrators except the father; however, the rabbi was not (see Table 4.1). There were also significant differences among the religious perpetrators. The incident with the priest was rated as significantly more serious (M = 8.56) than the incident with the rabbi (M = 8.41), t(52) = −2.43, p < .05. However, there was no significant difference between minister (M = 8.53) and the priest, F(1, 104) = 1.13, p > 0.05, R 2 = 0.00, or rabbi, F(1, 104) = 0.12, p > 0.05, R 2 = 0.01.

Study 2: Mock Juror Judgments in a CSA Trial

The mock juror experiment expanded upon the survey study to determine whether sentiment toward CSA perpetrators based on their relationship to the child influenced jurors’ verdicts in a mock trial. This study focused on three perpetrator–child relationships that have been common in the news in the past decade: priest, teacher, and coach. Study 1 showed that abuse by these three figures was seen as roughly equally serious (i.e., they did not differ significantly); nonetheless, because of the particularly highly publicized incidents of abuse by teachers and religious defendants, and community outrage associated with those events, we initially hypothesized that the teacher and the priest would be rated more negatively and receive more guilty verdicts than the coach. However, data collection for study 1 occurred prior to the scandal, and associated news coverage, criminal investigation, and trial, at Pennsylvania State University involving football coach Jerry Sandusky; data collection for study 2 occurred after the incident involving Coach Sandusky. This development suggested the competing hypothesis that if decisions were to follow community sentiment, then the coach would be rated more negatively and receive more guilty verdicts than the priest or the teacher (we will call this the Sandusky hypothesis).

Method. Participants were 86 undergraduates (74 % female, M age = 20.7, 77 % White, 15 % history of CSA) who received class credit for participation. Participants were randomly assigned to read a 22-page (6,642 words) trial transcript of a case that involved the inappropriate touching of a 13-year-old boy by a teacher, a priest, or a basketball coach. Details of the incident (e.g., nature of the touching, time, and place of occurrence) were held constant, as was the boy’s familiarity with the alleged perpetrator. The transcript included testimony from the child, the child’s therapist, the defendant, and a CSA expert. After reading the transcript, participants rendered a verdict (guilty or not guilty). Participants then rated how guilty they thought the defendant was on a 10-point Likert-type scale. Because jurors would rarely, if ever, determine sentencing in a CSA case, participants rated how severe a punishment the defendant should receive within the limits of the law on a 10-point Likert-type scale (ranging from “minimum permitted” to “maximum permitted”). Participants also rated their perceptions of the trial participants on the 13 questions from study 1 plus responsibility of the defendant on 10-point Likert-type scales (ranging from “not at all” to “extremely”). Participants then provided demographic information and were debriefed.

Results. Results were partially consistent with our hypotheses. As in study 1, the nine items were combined to create a “seriousness” scale, α = .92. Just as in study 1, despite the intervening Sandusky publicity, there were no differences in ratings as a function of the perpetrator–child relationship in study 2, F(2, 85) = 0.50, p > 0.05.

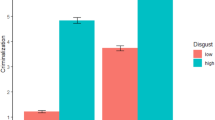

The five items that were not included on the seriousness scale were then analyzed. Results from these five items partially supported the Sandusky hypothesis (see Table 4.2). There were significant differences in ratings of the child’s responsibility, F(2, 83) = 3.77, p = 0.03, R 2 = 0.08; partially consistent with the Sandusky hypothesis, post hoc comparisons indicated the child was rated as significantly more responsible when the perpetrator was a teacher (M = 4.50) than when the perpetrator was a coach (M = 3.21; p < 0.05) or a priest (M = 2.79; p < 0.01). There was also a trend toward significance in ratings of the general likelihood of the event, F(2, 83) = 2.91, p = 0.06, R 2 = 0.07; partially consistent with the Sandusky hypothesis, the event was rated as marginally more likely when the perpetrator was a coach (M = 6.86) than when the perpetrator was a priest (M = 5.64; p < 0.05). The teacher (M = 6.00) did not differ from the coach or the priest (both ps > 0.05). However, there were no significant differences in ratings of the likelihood it was CSA, F(2, 85) = 0.76, p > 0.05, R 2 = 0.02, likelihood the child would report the event, F(2, 85) = 0.05, p > 0.05, R 2 = 0.00, or defendant’s responsibility, F(2, 85) = 0.20, p > 0.05, R 2 = 0.01.

We then conducted a binary logistic regression with perpetrator–child relationship as the independent variable and verdict (guilty or not guilty) as the outcome variable. Contrary to both of our hypotheses, perpetrator–child relationship did not influence verdict (Wald = 0.45, p = 0.50, OR = 0.83), ratings of guilt (F(2, 83) = 0.98, p = 0.38), or the degree of recommended punishment (see Table 4.2). Verdicts were roughly equal for all three perpetrators, with 53.6 % of participants finding the coach guilty, 56.7 % of participants finding the teacher guilty, and 46.4 % of participants finding the priest guilty.

Discussion

The goal of the current research was to examine how perceptions (i.e., sentiment) of CSA perpetrators varies based on the relationship between the child and the perpetrator, and whether those perceptions influence mock juror judgments. We surveyed college students initially using brief vignettes to assess the differences in perceptions of 13 different perpetrator–child relationships. Then, we had college students read a mock trial and render a verdict in a case that varied the (alleged) perpetrator–child relationship.

In CSA cases, jurors are supposed to follow the letter of the law, not commonsense justice (Finkel, 1995). The relationship between the perpetrator and the child is not a factor jurors are supposed to consider when making decisions about CSA cases. However, study 1 and study 2 both demonstrate that the relationship between the perpetrator and the child does influence perceptions of the incident in some circumstances. Moreover, these perceptions likely reflect community sentiment toward different perpetrator–child relationships. Prior to study 1, priests and teachers sexually abusing children had been concerns for the community, which was demonstrated in participants’ ratings of the crimes. However, in between study 1 and study 2, the Sandusky allegations arose, increasing community concern about coaches being potential CSA perpetrators. This change in community sentiment was reflected in the ratings of study 2, since participants rated the coach significantly worse on several elements than the study 1 participants (i.e., prior to Sandusky).

Although community sentiment was likely reflected in ratings of perceptions, it was not enough to result in differences in verdicts or recommended punishment. Thus, while jurors may perceive the perpetrators differently based on their relationship to the child, the types of perpetrator relationship did not impact the ultimate decision. It is not unusual for mock jury studies to find differences on some dependent measures (e.g., perceptions of the parties, credibility judgments) but not others (e.g., verdict; see Neal, Christiansen, Bornstein, & Robicheaux, 2012). One of the benefits of this study was that we were able to control for all other factors and manipulate only the relationship between the perpetrator and the child to isolate this variable. The controlled laboratory experiment allowed us to determine that despite different perceptions of the perpetrators, there was no significant difference in verdicts for the coach, the teacher, or the priest. Consequently, jurors may be able to overcome community sentiment toward these specific perpetrators in favor of applying the law.

Nevertheless, these results must be taken in context. Although the laboratory permitted us to isolate the perpetrator–child relationship, controlled laboratory studies also create challenges for jury researchers. The goal of much jury research, as an applied endeavor, is to understand how jurors make decisions in actual cases. However, it is often difficult for jury researchers to conduct studies that accurately mirror real-life situations. This study is not unique in this respect, and it exemplifies several common jury research challenges.

For example, one potential limitation is that our study used undergraduate students rather than community members. As Chamberlain and Shelton (Chap. 2) and Chomos and Miller (Chap. 6) suggest, one concern with these types of studies is that the sample is not representative of the community. Research has demonstrated that, in some situations, college students reflect different demographic characteristics (Reichert, Miller, Bornstein, & Shelton, 2011) and sentiment (Garberg & Libkuman, 2009) than actual jurors. However, research comparing college students to community members generally shows that there are few differences between the samples in terms of their trial-relevant judgments (Bornstein, 1999). Specifically in regard to CSA cases, undergraduates and community members do not differ substantially (Bottoms et al., 2007; Crowley, O’Callaghan, & Ball, 1994).

The present study, like most mock jury research, faces the larger challenge of ecological validity. The challenge of ecological validity in mock jury research is whether results from the controlled, artificial task can be applied or generalized to the real world and real juries (Finkel, 1995). For example, real juries make decisions that can have extreme, sometimes life or death consequences. In mock jury research, such as this study, participants are not under the same type of pressure to make the “right” decision (Bornstein & McCabe, 2005). This study faces the further problem that it does not involve deliberation. In the real world, six to twelve jurors (Williams v. Florida, 1970) deliberate and reach a decision. Research comparing studies that use individual mock jurors to studies that use deliberating mock juries indicates that, in general, mock juries reach comparable, though in some respects better, decisions than individual mock jurors (e.g., Devine, 2012). Thus, it is possible that different results would have been reached if this study used a deliberating jury.

Conclusion

Community sentiment research often focuses on general public opinion, but in the legal system, it is sometimes necessary to investigate the sentiment of specific subsets of the population who make the ultimate decisions. In criminal cases that go to a jury trial, the jury makes the ultimate decision about how to apply the law to the facts of the case. In some cases, the law requires the jury to take community sentiment into consideration. In most cases the jury is supposed to disregard community sentiment and apply the law objectively; however, even then, juries do have the capability to nullify. In the vast majority of cases, nullification does not occur, but community sentiment still has the potential to influence jury verdicts. The present studies focused on laypeople’s and mock jurors’ perceptions of CSA perpetrators as a function of the relationship of the perpetrator and the child. Although both studies showed that CSA is perceived differently depending on who the alleged perpetrator is, there were no differences in verdicts for different perpetrators, at least for the limited set of potential perpetrators under investigation here.

Future research should focus on increasing ecological validity, such as by including deliberation and/or by conducting analogous research using divergent methodologies. Archival analyses of CSA cases yield results that are similar to results of jury simulations in some respects but that differ in some ways as well (Read et al., 2006). Techniques like group deliberation and non-laboratory jury research are beneficial in that, like experimental studies of individual mock jurors, they allow inferences about community sentiment and, insofar as they provide results consistent with other methodologies, improve our understanding of both juror and jury behavior.

References

Allen, L. A., & Nightingale, N. N. (1997). Gender differences in perception and verdict in relation to uncorroborated testimony by a child victim. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 24, 101–116. doi:10.1300/J076v24n03_06.

Berry, J. (1992). Lead us not into temptation: Catholic priests and the sexual abuse of children. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Bolton, J. F. G., Morris, L. A., & MacEachron, A. E. (1989). Males at risk: The other side of child sexual abuse. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Bornstein, B. H. (1999). The ecological validity of jury simulations: Is the jury still out? Law and Human Behavior, 23(1), 75–91. doi:10.1023/A:1022326807441.

Bornstein, B. H. (in press). Jury simulation research: Pros, cons, trends and alternatives. In M.B. Kovera (Ed.), The psychology of juries: Current knowledge and a research agenda for the future. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bornstein, B. H., Kaplan, D. L., & Perry, A. R. (2007). Child abuse in the eyes of the beholder: Lay perceptions of child sexual and physical abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 375–391. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.09.007.

Bornstein, B. H., & McCabe, S. G. (2005). Jurors of the absurd? The role of consequentiality in jury simulation research. Florida State University Law Review, 32, 443–467.

Bornstein, B. H., & Muller, S. L. (2001). The credibility of recovered memory testimony: Exploring the effects of alleged victim and perpetrator gender. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25, 1415–1426. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00282-4.

Bottoms, B. L. (1993). Individual differences in perceptions of child sexual assault victims. In G. S. Goodman & B. L. Bottoms (Eds.), Child victims, child witnesses: Understanding and improving testimony (pp. 229–261). New York, NY: Guilford.

Bottoms, B. L., Golding, J. M., Stevenson, M. C., Wiley, T. R., & Yozwiak, J. A. (2007). A review of factors affecting jurors’ decisions in child sexual abuse cases. In M. Toglia, J. D. Read, D. F. Ross, & R. C. L. Lindsay (Eds.), Handbook of eyewitness psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 509–543). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bottoms, B. L., & Goodman, G. S. (1994). Perceptions of children’s credibility in sexual assault cases. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24, 702–732. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1994.tb00608.x.

Crowley, M. J., O’Callaghan, M., & Ball, P. J. (1994). The judicial impact of psychological expert testimony in a simulated child sexual abuse trial. Law and Human Behavior, 18, 89–105. doi:10.1007/BF01499146.

Devine, D. J. (2012). Jury decision making: The state of the science. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Devine, D. J., Clayton, L. D., Dunford, B. B., Seying, R., & Pryce, J. (2001). Jury decision making: 45 years of empirical research on deliberating groups. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 7, 622–727.

Diamond, S. S. (1997). Illuminations and shadows from jury simulations. Law and Human Behavior, 21, 561–571. doi:10.1023/A:1024831908377.

Dollar, K. M., Perry, A. R., Foromouth, M. E., & Holt, A. R. (2004). Influence of gender roles on perceptions of teacher/adolescent student sexual relations. Sex Roles, 50, 91–100. doi:10.1023/B:SERS.0000011075.91908.98.

Drugge, J. E. (1992). Perceptions of child sexual assault: The effect of victim and offender characteristics and behavior. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 18, 141–165. doi:10.1300/J076v18n03_12.

Finkel, N. J. (1995). Commonsense justice: Jurors’ notions of the law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Finkelhor, D., Hotaling, G., Lewis, I. A., & Smith, C. (1990). Sexual abuse in a notional sample of adult men and women: Prevalence, characteristics, and risk responsibility. Child Abuse & Neglect, 14, 19–28. doi:10.1016/0145-2134(90)90077-7.

Finkelhor, D., & Redfield, D. (1984). How the public defines sexual abuse. In D. Finkelhor (Ed.), Child sexual abuse: New theory and research (pp. 107–133). New York, NY: Free Press.

Finlayson, L. M., & Koocher, G. P. (1991). Professional judgment and child abuse reporting in sexual abuse cases. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 22, 464–472. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.22.6.464.

Ganim, S. (2011, November 17). Exclusive: Jerry Sandusky interview prompts long-ago victims to contact lawyer. Patriot News. Retrieved from http://www.pennlive.com/midstate/index.ssf/2011/11/exclusive_jerry_sandusky_inter.html

Garberg, N., & Libkuman, T. (2009). Community sentiment and the juvenile offender: Should juveniles charged with felony murder be waived into the adult criminal justice system? Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 27(4), 553–575. doi:10.1002/bsl.869.

Golding, J. M., Sanchez, R. P., & Sego, S. A. (1997). The believability of hearsay testimony in a child sexual assault child. Law and Human Behavior, 21, 299–325. doi:10.1023/A:1024842816130.

Golding, J. M., Sego, S. A., Sanchez, R. P., & Hasemann, D. (1995). The believability of repressed memories. Law and Human Behavior, 19, 569–592. doi:10.1007/BF01499375.

Goodman, G. S., Quas, J. A., Bulkley, J., & Shapiro, C. (1999). Innovations for child witnesses: A national survey. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 5, 255–281. doi:10.1037/1076-8971.5.2.255.

Hamm, J. A., Bornstein, B. H., & Perkins, J. (2013). Jury nullification: The myth revisited. In D. Fung (Ed.), Psychology of policy-making (pp. 49–71). Hauppauge, NY: Nova.

Horowitz, I. A., Kerr, N. L., & Niedermeier, K. E. (2001). Jury nullification: Legal and psychological perspectives. Brooklyn Law Review, 66, 1207–1249.

Imrich, D., Mullin, C., & Linz, D. (1995). Measuring the extent of prejudicial pretrial publicity in major American newspapers: A content analysis. Journal of Communication, 45, 94–117. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1995.tb00745.x.

Irvine, M., & Tanner, R. (2007, October 21). Sexual misconduct plagues US schools. Associated Press. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/10/21/AR2007102100144_pf.html

Isquith, P., Levine, M., & Scheiner, J. (1993). Blaming the child: Attribution of responsibility to victims of child sexual abuse. In G. S. Goodman & B. L. Bottoms (Eds.), Child victims, child witnesses: Understanding and improving testimony (pp. 203–228). New York, NY: Guilford.

Kahneman, D., Schkade, D., & Sunstein, C. R. (1998). Shared outrage and erratic awards: The psychology of punitive damages. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 16, 49–86. doi:10.1023/A:1007710408413.

Kendall-Tackett, K. A., Williams, L. M., & Finkelhor, D. (1993). Impact of sexual abuse on children: A review and synthesis of recent empirical studies. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 174–180. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.164.

King, N. J. (1998). Silencing nullification advocacy inside the jury room and outside the courtroom. The University of Chicago Law Review, 65, 433–500.

Kovera, M. B., & Borgida, E. (2010). Social psychology and law. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (Vol. II, pp. 1343–1385). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Kovera, M. B., Borgida, E., Gresham, A. W., Swim, J., & Gray, E. (1993). DO child sexual abuse experts hold partisan beliefs? A national survey of the society for traumatic stress studies. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6, 383–404. doi:10.1002/jts.2490060308.

Kovera, M. B., Levy, R. J., Borgida, E., & Penrod, S. D. (1994). Expert witnesses in child sexual abuse cases: Effects of expert testimony and cross-examination. Law and Human Behavior, 18, 653–674. doi:10.1007/BF01499330.

Leipold, A. (1996). Rethinking jury nullification. Virginia Law Review, 82, 253–324.

Marder, N. S. (1999). The myth of nullifying the jury. Northwestern University Law Review, 93, 877–959.

Maynard, C., & Wiederman, M. (1997). Undergraduate students’ perceptions of child sexual abuse: Effects of age, sex, and gender-role attitudes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 21, 833–844. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00045-8.

Miller v. California (1973). 413 U.S. 15.

Myers, J. E. B. (1998). Legal issues in child sexual abuse and neglect (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Myers, J. E. B. (2008). A short history of child protection in America. Family Law Quarterly, 42, 449–464.

Myers, J. E., Redlich, A., Goodman, G., Prizmich, L., & Imwinkelried, E. (1999). Juror’s perceptions of hearsay in child sexual abuse cases. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 5, 388–419. doi:10.1037/1076-8971.5.2.388.

Neal, T. M. S., Christiansen, A., Bornstein, B. H., & Robicheaux, T. R. (2012). The effects of jurors’ beliefs about eyewitness performance on verdict decisions. Psychology, Crime and Law, 18, 49–64. doi:10.1080/1068316X.2011.587815.

O’Donohue, W., Smith, V., & Schewe, P. (1998). The credibility of child sexual abuse allegations: Perpetrator gender and subject occupational status. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 10, 17–24. doi:10.1023/A:1022150413977.

Orcutt, H. K., Goodman, G. S., Tobey, A., Batterman-Faunce, J., Thomas, S., & Shapiro, C. (2001). Detecting deception: Factfinders’ abilities to assess the truth. Law and Human Behavior, 25, 337–370. doi:10.1023/A:1010603618330.

Pennsylvania v. Ritchie (1987). 480 U.S. 39.

Pennsylvania v. Sandusky (2013). 2013 PA Sup. 264.

Read, J. D., Connolly, D. A., & Welsh, A. (2006). An archival analysis of actual cases of historic child sexual abuse: A comparison of jury and bench trials. Law and Human Behavior, 30, 259–285. doi:10.1007/s10979-006-9010-7.

Reichert, J., Miller, M. K., Bornstein, B. H., & Shelton, D. (2011). How reason for surgery and patient weight affect verdicts and perceptions in medical malpractice trials: A comparison of students and jurors. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 29, 395–418. doi:10.1002/bsl.969.

Scheflin, A. W. (1972). Jury nullification: The right to say no. The California Law Review, 45, 168–226.

Schutte, J. W., & Hosch, H. M. (1997). Gender differences in sexual assault verdicts: A meta-analysis. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 12, 759–772.

Simson, G. J. (1976). Jury nullification in the American system: A skeptical view. Texas Law Review, 54, 488–525.

Smith, H. D., Foromouth, M. E., & Morris, C. (1997). Effects of gender on perceptions of child sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 6, 51–63. doi:10.1300/J070v06n04_04.

Snyder, H. N. (2000). Sexual assault of young children as reported to law enforcement: Victim, incident, and offender characteristics. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Spano, L. M., Groscup, J. L., & Penrod, S. D. (2011). Pretrial publicity and the jury: Research and methods. In R. L. Wiener & B. H. Bornstein (Eds.), Handbook of trial consulting (pp. 217–244). New York, NY: Springer.

Sparf and Hansen v. United States (1865). 156 U.S. 51.

Steblay, N. M., Besirevic, J., Fulero, S. M., & Jimenez-Lorente, B. (1999). The effects of pretrial publicity on juror verdicts: A meta-analytic review. Law and Human Behavior, 23, 219–235. doi:10.1023/A:1022325019080.

United States v. Spock (1969). 416 F. 2d 165.

Van Dyke, J. (1970). The jury as a political institution. Catholic Law Review, 16, 224–270.

Vidmar, N. (1997). Generic prejudice and the presumption of guilt in sex abuse trials. Law and Human Behavior, 21, 5–25. doi:10.1023/A:1024861925699.

Vieth, V. (2005). Unto the third generation: A call to end child abuse in the United States within 120 years. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma, 12, 5–54. doi:10.1300/J146v12n03_02.

Whitcomb, D., Shapiro, E., & Stellwagen, L. (1985). When the victim is a child: Issues for judges and prosecutors. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

Wiener, R., Krauss, D., & Lieberman, J. (2011). Mock jury research: Where do we go from here? Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 29, 467–479. doi:10.1002/bsl.989.

Williams v. Florida (1970). 399 U.S. 78.

Yozwiak, J. A., Golding, J. M., & Marsil, D. F. (2004). The impact of type of out-of-court disclosure in a child sexual assault trial. Child Maltreatment, 9, 325–334. doi:10.1177/1077559504266518.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Reed, K., Bornstein, B.H. (2015). Using Mock Jury Studies to Measure Community Sentiment Toward Child Sexual Abusers. In: Miller, M., Blumenthal, J., Chamberlain, J. (eds) Handbook of Community Sentiment. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-1899-7_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-1899-7_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4939-1898-0

Online ISBN: 978-1-4939-1899-7

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)