Abstract

Nicaragua has the second highest rate of adolescent pregnancy in all of Latin America. This reality coupled with the significant poverty nationwide and reduction in aid in tough economic times presents many challenges for this Central American country. Nicaragua, however, is unique for Central America in which it has a vibrant history rooted in activism and fighting for social and economic justice. The information in this chapter will provide a historical context, current psychosocial, public health, and medical conditions, in the country, and recommendations for future policy and practice. One of the major preventative factors in terms of maternal and infant health is access and quality of health care services. Women in Nicaragua who do not have access to good health services are more likely to suffer complications in pregnancy, labor, and delivery. Additionally, adolescents with higher educational levels and career aspirations are more likely to defer marriage and parenting until later on in life. Until 2006, abortion was legal in Nicaragua when the health and life of the mother was in danger. In 2006, however, the National Assembly of Nicaragua enacted and the president signed a total ban of abortion in Nicaragua. This ban includes any form of medical attention to pregnant girls and women that may endanger the life of the fetus, including treatment for cancer, HIV/AIDS, malaria, or cardiac emergencies. The law also makes no distinction between abortion and miscarriage, thus potentially violating the human rights of women who experience a miscarriage through no fault of their own. Finally, the law criminalizes medical practitioners who provide any treatment to pregnant females that endanger the life of the unborn child. Since the total ban on abortion was enacted, maternal deaths have increased. There has also been an increase in pregnant teenagers committing suicide.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Nicaragua: abortion

- Adolescent pregnancy

- Adolescent sexual activity

- Barriers to birth control

- Child labor laws

- HIV/AIDS

- Human trafficking

- Partner violence

- Reproductive health

- Sexual and reproductive health

Introduction

Nicaragua is resilient. In the last century alone, the country has been through 20 years of occupation under the US Marines, 40 years of dictatorship, 10 years of a civil war with over 22,000 citizens killed, and over 20 years of democratically elected presidents. In addition, the country has survived a massive earthquake, two major hurricanes, and numerous volcanic eruptions within the second half of the past century alone. With each challenge, the country has persevered and moved forward. This dedication and perseverance is evident regarding social issues as well. Advances that began with the Sandinista Revolution in terms of health care, education, and gender equality have continued to grow. Although the country suffers from poverty and the litany of issues that ensue, the people of Nicaragua are resilient, inquisitive, and passionate about social change. This dedication is evident in the genuine and forthcoming ways in which the country has embraced the challenge of prevention and intervention related to adolescent pregnancy.

Historical Background

From 1936–1979, Nicaragua was under the oppressive rule of the Somoza dictatorship. The divide between the rich and the poor was wide, illiteracy rates were high, and human rights violations were numerous. The Somoza family, however, had the crucial support of the United States, and the last of the series of dictators, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, was even trained at West Point (Somoza 1980). This family regime continued until 1972 when a major earthquake destroyed the capital city of Managua two days before Christmas, killing over 6,000 individuals. International aid flowed into the country, but nearly all of it was diverted by Somoza for his family and friends (Brancati 2007). This corruption signaled the end of the Nicaraguan people’s tolerance of the authoritarian rule.

The Nicaraguan people, under the leadership of the Sandinista National Liberalization Front (Frente Sandinista de Liberalización Nacional-FSLN), mobilized and overthrew Somoza on July 19, 1979. The Sandinistas inherited a country rife with poverty, illiteracy, and disease. Under the leadership of the Junta of Five, the Sandinistas worked to restore peace, justice, and human rights to Nicaragua. Illiteracy rates, for example, were reduced from 50 to 13 % in 2 years (Arnove 1981; Hanemann 2005). In 1984, through the first free elections in the history of the country, Daniel Ortega was elected president.

The Sandinista party, however, was a threat to the United States. The party’s socialist practices, modeled after and supported by Cuba, led to friction and distrust with the United States during the Cold War era. The USA via ruthless and controversial means funded the Contra opposition, cut foreign aid to Nicaragua, and eventually instituted a full trade embargo. A violent civil war followed in which an estimated 30,000 Nicaraguans were killed. Weary of political unrest and war, the Nicaraguans elected a candidate favored by the US Violeta Chamorro, to the presidency in 1990, thus leading to a new era of more moderate government and improved relations with the United States.

The country maintained relative stability during the 1990s and continued to grow both socially and economically. In 1998, however, another natural disaster, Hurricane Mitch, slammed into the country, destroying 70 % of the country’s infrastructure and killing 4,000 individuals. Nearly 10 years later, just as the country had begun to recover, a Category 5 Hurricane Felix hit, destroying 95 % of the infrastructure and 99 % of the crops in the Atlantic region. The economic damage was devastating and led to a spike in inflation and economic despair (NicaNet 2007; World Bank 2009). The subsequent worldwide financial crisis of 2009 has only further limited Nicaragua’s economic recovery in terms of growth and development.

Nevertheless, Nicaragua remained resilient in terms of progress in social issues and public health. The Sandinista government expanded the education system into rural areas, established lay health care models, and focused attention on women’s rights, which set Nicaragua on a different trajectory from other counties in Central American. Many of the traditional norms in terms of gender roles and family dynamics are not as prominent or adhered to. In this environment, women have taken advantage of opportunities to further their education and make informed decisions on their health care needs. The efforts in the 1980s to increase literacy rates, improve health, and mobilize rural communities continue to have an impact on Nicaragua, including the ways in which the country, as a whole, addresses issues related to sexual health, reproduction, and contraception.

Current Status

Nicaragua has a population of approximately 5.5 million individuals (United Nations [UN] 2011). Over 1 million individuals live in the capital city of Managua. Nicaragua is the second poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. Over 56 % of the population lives below the poverty line with an annual per capita income of $1228 (UN 2011). The country is predominantly rural and depends on agriculture, which makes up 20 % of the GDP, 40 % of the labor force, and 60 % of the country’s exports (Arce 2009). Nearly 10 % of the eligible workforce population is unemployed (UN 2011). Of the entire population, 32 % lives at an income under $2 per day (Population Council 2011). Although fertility rates have declined, there is a division between the rates of the wealthiest 20 % of the population (1.8 children) and the poorest 20 % of the population (4.5 children) (Indacochea and Leahy 2009). Nicaragua currently ranks nineteenth in the world in terms of the gap between the wealthiest 10 % of the population and the poorest 10 % of the population with a 31.1 ratio (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP] 2010). Although these data present the realities of social inequality within the country, Nicaragua has a smaller gap between the rich and the poor than most other countries in Central America with the exception of Belize and Costa Rica (Arriagada 2002; UNDP 2010).

Nicaragua is a predominantly Spanish-speaking country rooted in a mix of Catholic values and indigenous practices. Approximately 90 % of the population speaks Spanish, although in the two autonomous regions of the Atlantic coast, other languages including Creole English, Miskito, and Garifuna are prevalent (Grinevald 2007). An estimated 73 % of the population is identified as Roman Catholic, 15 % are evangelical Christians, and the remainder includes, among others, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Moravian, Judaism, and Muslim (United Nations Statistics Division [UN Data] 2010). The percentage of people identified as Roman Catholic has steadily declined over the past 20 years, and this trend is estimated to continue in the future. There is a distinct difference between the Atlantic region and the rest of Nicaragua. In the two Atlantic regions, culture is rooted in communities such as Miskito, Garifuna, and Afro-Caribbean. The majority of the population in these regions speaks an indigenous language or Creole English and practices the Moravian faith (UN Data 2010). These differences between the east and west coast are significant when analyzing sexual health and reproduction practices and policies countrywide. The eclectic mix of cultures means that health care and human service workers must design pregnancy prevention programs that are region-specific.

Economic Development

The Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) and other similar policies have had an impact on modernization and economic growth in Nicaragua. Nicaragua has traditionally been a rural area, but current trend indicates that the urban sector is growing more rapidly than the rural sector. Part of this growth is, in part, due to Nicaragua’s membership into CAFTA in 2005. Nicaragua is one of the many Central American countries that signed a free trade agreement with the United States during the past 10 years. This policy, similar to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), removes restrictions on trade, making it easier for companies from the USA to relocate to Central America. CAFTA has not been an entirely positive step for Nicaragua. Although the policy has created jobs, the agreement has undermined agricultural growth. Nicaraguan farmers are unable to compete with subsidized agriculture from the United States and cannot compete with the market of corn, beans, rice, and dairy (Campbell et al. 2010).

The most current data from the United Nations (2011) indicate that over half (56 %) of the population lives in urban areas with Managua as the largest metropolitan center. The population growth of individuals in the urban sector was 1.8 % from 2005 to 2010 as compared to 0.7 % growth in the rural sector for the same time frame (UN 2011). One of the most telling indicators of modernization has been in cell phone use. From 2000 to 2008, the number of subscribers increased from 5.0 to 59.1 % of the population. The number of Internet users has also increased from 1.0 to 3.3% of the population. This is significant in terms of adolescent health because the number of youth accessing online communities has grown. Some of the major adolescent health programs, such as ProFamilia (the Nicaraguan branch of International Planned Parenthood), are now online in Websites and even in Facebook pages.

Children and Adolescents

Nicaragua is a young country. Specially, 35 % of the population is under the age of 14 and 20 % is between the ages of 15 and 24. The under-five mortality rate has decreased from 68 % in 1990 to 26 % in 2009 (United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF] 2010). Adolescent ages 10–19 make up 23 % of the population. More adolescent girls than boys are enrolled in secondary school (UNICEF 2010). The life expectancy has increased from 57 in 1970 to 73 in 2009.

Girls are excelling at a higher rate than boys in terms of education and literacy rates. The literacy rate for persons aged 15–24 is 85 % for men and 89 % for women (UNICEF 2010). Although the enrollment ratio in primary schools is higher for boys than girls, the attendance ratio is higher for females than males in both primary and secondary schools at 77/84 and 35/47, respectively (UNICEF 2010). Enrollment rates are also higher for women than men in higher education (Global Movement for Children 2010). Conversely, more boys than girls are part of the child labor population (UNICEF 2010).

Child Labor

Although child labor laws prohibit children under the age of 14 from being employed, 11 % of all children in Nicaragua are working in child labor (United States Department of Labor [DOL] 2010). Many of the children work in agriculture, harvesting cotton, tobacco, coffee, bananas, and rice. An estimated 4,000–5,000 children work in the streets of Managua as beggars, cleaning windows, or selling goods (United States Department of State [DOS] 2009). The International Labour Office has been working with Nicaragua on several initiatives to reduce child labor in garbage dumps, prostitution rings, and coffee plantations (International Labour Office [ILO] 2007). Education is free and mandated through sixth grade although it is generally not enforced (DOS 2009). Children from backgrounds of poverty are at a greater risk of not attending school and of being forced into child labor.

Human Trafficking and Prostitution

A growing number of Nicaragua children are involved with child prostitution. Many of these girls work along the port cities and the borders of Honduras and Costa Rica. Others stay along the Pan-American Highway, working as prostitutes for truck drivers traveling through Latin America. A survey was conducted by the Ministry of Family to investigate child prostitution in Nicaragua (DOS 2009). The results showed that many of the girls enter into prostitution to help their families pay for food, clothing, and shelter. Others engage in sexual practices to support drug habits. A growing number of children are trafficked and sold into sex slavery. The 2010 Trafficking in Persons Report discussed the issue of women and children being sold into slavery and forced into sex workers in Managua (DOS 2010). Recommendations are for stricter enforcement of human trafficking and more public awareness campaigns to increase prevention.

Health Care

The delivery of health care in Nicaragua, like in many parts of Latin America, is based on a three-tiered approach. For the wealthiest segment of the population, there is private, out-of-pocket medical care. Persons formally employed in the country receive services through the Social Security Institute (INSS). The INSS is funding through mandatory salary contributions on behalf of employees. INSS then contracts with private health firms to provide services to employees and their families in both public and private settings. Finally, the Ministry of Health (Ministerio de Salud-MINSA) provides free, public health care to the rest of the population including the unemployed and persons living in poverty (Angel-Urdinola et al. 2008; World Health Organization 2001).

With the assistance of the World Bank, Nicaragua has embarked on a healthcare reform initiative designed to improve efficient, effective, and sustainable delivery of services to poor and underserved communities. The Modernization and Expansion of Health Services included two phases (Indacochea and Leahy 2009; Regalia and Castro 2007). The first phase focused on improving the management of healthcare via a national organization (MINSA) and local care administered through decentralized, regional operations (Sistemas Locales de Atención Integral en Salud-SILAIS). This system allowed for more regional control and responsibility for health care services. The second phase of this reform has centered on ways to improve access and delivery of health care to the poor and underserved through free and universal health care. Part of this phase included a cash-transfer incentive program for families in poverty, modeled after a similar program in Mexico (Regalia and Castro 2006). In reality, however, there has been difficulty in funding services at the local level. Consequently, free healthcare is more a goal than a reality.

The Nicaraguan administration, in conjunction with MINSA and SILAIS, is committed to the management and distribution of contraceptives nationwide. One of the responsibilities of MINSA and SILAIS is to monitor the supply and distribution of contraceptives and to provide community-based education on pregnancy prevention. MINSA provides an organized and detailed plan regarding contraceptives and family planning. The guidelines address the responsibilities of both men and women in family planning (MINSA 2008). One of the challenges for Nicaragua is in maintaining a consistent and adequate supply of contraceptives. There have been times when local health clinics have either been overstocked or have run out of certain methods of prevention. MINSA has been working to better coordinate supplies and maintain updated inventories, especially in poor, rural, and remote areas.

The government has been consistent in its willingness to address the issue of contraceptives and family planning. In 2003, the Contraceptive Security Committee (Comité de Disponibilidad Asegurada de Insumos Anticonceptivos-DAIA) was formed. It is a public/private partnership of organizations committed to family planning. Its focus was to better coordinate and streamline services (Betancourt 2007). The government partnered with USAID in a plan where they would assume 25 % of the cost of providing contraceptives in 2008, 60 % in 2009, and 100 % in 2010 (Deliver 2007). In 2008, the government allotted 40 % of the funding for condoms, IUDs, injections, and oral contraception. One of the strengths of this provision of contraceptives has also been one of the country’s greatest challenges. The national campaign, nevertheless, was successful in increasing family planning with an emphasis on injections, IUDs, and condoms. Local health clinics were consistent in promoting these forms of protection, and women, especially, took advantage of this initiative. As a result, MINSA has had to contend with an increased demand for Depo-Provera, oversupply of condoms (men’s reluctance and/or interest in condoms continues), and the reality that there is no manufacturing of contraceptives nationwide (Indacochea and Leahy 2009). With difficult economic times, the country now struggles with how to maintain a steady supply of contraceptives and how to keep the momentum for family planning alive.

There are several international partnerships committed to reproductive health in Nicaragua. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) have historically been the primary funders of contraceptives. USAID’s donations, however, in the form of condoms, DepoProvera, and oral contraceptives, have been phased out over the years with the understanding that the Nicaraguan government will take over the financing of contraceptives (Deliver 2007). The current economic situation, however, has made financing difficult, and other international agencies through Finland, Spain, the European Union, the United Nations Children’s Fund, UNFPA, and the World Bank have been instrumental in providing contraceptives (Indacochea and Leahy 2009). Private NGOs such as ProFamilia (the Nicaraguan branch of the International Planned Parenthood Federation), PanAmerican Social Marketing Organization, and NicaSalud have also been involved in the distribution of information and services related to family planning (Indacochea and Leahy 2009). Finally, Cuba and Venezuela have worked in solidarity with Nicaragua on health care issues. Cuba’s assistance has been in the form of medical training and provisions in rural areas. Venezuela, through reduced costs of oil, mandates that the savings be applied by the Nicaraguan government to health care and medications.

Health and sanitation conditions have improved countrywide. In 2008, 98 % of the urban areas and 68 % of the rural areas had improved drinking water facilities (UNICEF 2010). Sanitation in both urban and rural areas has improved as well. In terms of prevention, most infants under the age of 1 year have been immunized against tuberculosis (98 %), DPT (98 %), polio (99 %), measles (99 %), hepatitis B (98 %), and tetanus (80 %). There is a decline, however, in medical treatment of children under 5 years of age for diarrhea (49 % receiving oral rehydration) and pneumonia (58 %) and limited provisions of anti-malarial drugs (UNICEF 2010).

Adolescents and Sexual Activity

It is not uncommon for adolescents in developing countries with high fertility rates to become pregnant and/or marry at an early age. There are over 14 million births to adolescents worldwide, and the majority of these births occur in impoverished nations (Bearinger et al. 2007; Westoff 2003). In Latin America, between 13–25 % of all adolescent girls are pregnant or mothers (Reynolds et al. 2006). Some of the reasons for high rates of adolescent pregnancies in developing nations include lack of information about birth control, unavailable and/or limited access to contraceptives, and cultural factors. Religion, especially in nations that are predominantly Roman Catholic, plays a role as well although the past decade has seen an increase in acceptance of birth control, regardless of religion. In Latin America, for example, the machismo culture reinforces manliness through the number of children and number of partners a man has (Sternberg 2000). A man’s virility is often determined by the number of his partners and offspring. This culture puts pressure on boys to become sexually active at a young age.

Adolescent Pregnancy in Developing Countries

Worldwide, there are serious medical risks involved with having children at a young age. Teenage girls who become pregnant are at a 2–4 times greater risk of death than women who give birth over the age of 20 (Reynolds et al. 2006). Children born to these mothers are at a higher risk of being at low birth weights and/or infant mortality. Infants born to teenage mothers are 35 % more likely to die before the age of one and 26 % more likely to die before the age of five (Bicego and Ahmad 1996). Poverty, cultural factors promoting early marriages, distance to health care facilities, and inadequate healthcare all contribute to increased health risks for adolescent mothers and their children (McCarthy and Maine 1992).

One of the major preventative factors in terms of maternal and infant health is access and quality of health care services. Women in developing countries with good health services are more likely to suffer fewer complications in pregnancy, labor, and delivery (Bicego and Ahmad 1996; Reynolds et al. 2006). As well, babies born with higher birth weights are less likely to die in infancy. Mothers are less likely to contract parasitic malarial infections and other diseases that may harm both mother and child. Access to quality health care also insures better delivery services and, if needed, emergency care (Reynolds et al. 2006).

Another issue related to health care and adolescents is the willingness to seek medical attention. Adolescents under the age of 18 are less likely to obtain prenatal care than mothers between the ages of 18–34 (Reynolds et al. 2006). These mothers are also less likely to access quality delivery services, thus compounding risks for safe deliveries. The health risks continue after delivery as children born to mothers under the age of 20 were less likely to receive necessary immunizations, regardless of availability of services (Reynolds et al. 2006). Poverty is strongly related with maternal and child health as well. Pregnant girls in high-poverty environments are less likely to access prenatal, delivery, and immunization services (Reynolds et al. 2006). Poverty is a predictor of teenage girls’ low access of health services.

Adolescent Pregnancy in Nicaragua

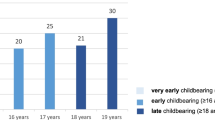

The percentage of adolescent pregnancies in Nicaragua is the highest of all countries in Latin America. The average age of the onset of sexual intercourse is 17.8 years for girls (Meuwissen et al. 2006b, c). Among girls aged 15–19, 22 % are either married or in a partnership. Of women aged 20–24, 28 % had given birth before the age of 18 (UNICEF 2010). There are 119 births annually per 1,000 women aged 15–19 (Meuwissen et al. 2006a, d). Almost half of women under the age of 20 in Nicaragua give birth, and 25 % of all births in the country are to women under the age of 20 (Lion et al. 2009). While the fertility rates of women as a whole in Nicaragua have dropped 26 % from 1990 to 2005, the rates for women aged 15–19 have only dropped 11 % (Lion et al. 2009). The latest Demographic and Health Survey of Nicaragua also showed a slight increase in the number of teenage pregnancies from 17.9 % in 2001 to 19.6 % in 2008 (Instituto Nacional de Desarollo de Información [INDIE] 2006). Furthermore, more than half of all mothers aged 20–24 gave birth to their first child under the age of 20 (Rani et al. 2003). The rate of unplanned teenage pregnancy is also increasing (Instituto Centroamericano de Salud 2007).

Adolescent pregnancy and health care services follow the typical patterns in the developing world. Adolescent pregnancy in Nicaragua is inversely related to access of prenatal care. Women who gave birth under the age of 18 are less likely to take advantage of prenatal services than older women. These women are also less likely to take their children for rounds of immunizations (Reynolds et al. 2006). This reality points to the need for systematic education and program development that targets the maternal and child health of adolescents and their offspring.

Adolescent Pregnancy and Risk Factors

Adolescent pregnancy is correlated with low educational levels and high levels of poverty. Some of the risk factors associated with teenage pregnancy in Nicaragua are low self-esteem, high levels of poverty, and increased chance of dropping out of school (Samandari and Spencer 2010). With adolescent pregnancy comes an increased danger of being ostracized and banished from close family connections at the very time when those connections are most needed. While boys are encouraged to become sexually active at a young age and to fulfill some of the preconceived notions of “machismo,” women have traditionally been expected to refrain from engaging in premarital sex (Pittman et al. 2010; Sternberg 2000). These expectations, however, do not come with accompanying discussions with adolescent girls about reproductive health. A common belief in families is that talking about sexuality will encourage adolescents to experiment, and therefore, it is better to not engage teenage girls in conversations about reproduction (Pittman et al. 2010).

Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic status plays a significant role in the likelihood that adolescent girls will become pregnant. Studies show that girls from educated, middle- and upper-class families were less likely to have engaged in sexual intercourse at a young age or given birth (Samandari and Speizer 2010). Furthermore, there is a high correlation between socioeconomic status, educational level, and living in an urban area with using contraceptives and being in a stable, consensual relationship (Samandari and Speizer 2010). Adolescents with higher educational levels and career aspirations are more likely to defer marriage and parenting until later on in life. In addition, girls living in urban areas have more frequent and easier access to contraceptives. These adolescents are also more likely to use a modern method of contraception such as oral contraceptives, injections, and/or condoms rather than relying on natural methods (Samandari and Speizer 2010). Finally, girls from wealthier families in urban areas are more likely to delay marriage and/or consensual unions until after completion of higher education and career goals (Samandari and Speizer 2010). There is definitely a shift going on in Nicaraguan culture around gender roles and expectations.

Sexually Transmitted Illnesses and HIV

Sexually transmitted illnesses and HIV prevalent among adolescents are related to education and socioeconomic status as well. Much of the population is at risk of these diseases because of low use of contraceptives and other methods of birth control (Berglund et al. 1997). The majority of teenagers report having an understanding and awareness of contraceptives but are not informed on best practices and the strengths and limitations of each form of protection. Furthermore, men report feeling as if their machismo is compromised when using condoms and prefer that the woman use pills or other forms of contraceptives rather than condoms (Manji et al. 2007). These beliefs regarding condom usage put young men and women at a high risk for catching sexually transmitted infections and the HIV virus (Manji et al. 2007). Women are also at high risk of cervical cancer, ovarian cancer, and complications from pregnancies.

Prenatal Care

Only a fraction of adolescent girls receive prenatal care, and the care is directly proportional to proximity to advanced health care settings and individuals trained in childbirth and OBGYN practices. Adolescent women are less likely to visit a health clinic and are less likely to receive prenatal services throughout their pregnancy (Lion et al. 2009). These services are directly proportional to proximity to urban areas. The closer a woman is to an urban area, the more likely it is that she will receive prenatal services. In rural areas, adolescent girls are less likely to seek medical care during pregnancy. Human Rights Watch has stated that 40 % of all maternal deaths in rural areas of Nicaragua are to girls under the age of 19 (Silva 2010). There is concern that the divide between urban and rural areas in terms of health care is widening and that women in remote areas are at a greater risk of not receiving necessary prenatal and emergent care.

Cycle of Adolescent Pregnancy

There are risks in terms of the cycle of adolescent pregnancy. Mothers who give birth under the age of 15 are more likely to have their own daughters give birth as teenagers (Berguland et al. 1997). This is especially true with women from Latin American (Rowlands 2010; Lau and Flores 2010). This reality has much to do with socioeconomic factors that are passed down from generation to generation. Low self-esteem becomes a compounding factor as well. Young girls growing up in poverty with little hope of socioeconomic advancement are more likely to fear abandonment and isolation that then challenges associated with teenage pregnancy (Berguland et al. 1997). Mothers who first become pregnant as adolescents are also likely to have more children overall than mothers who delay the onset of their first pregnancy.

Barriers to Birth Control

The percentage of women using birth control in Nicaragua has steadily increased. Currently, 75 % of women aged 15–49 use some form of birth control (INDIE 2006). Historically, there was a belief that religious practices associated with the Roman Catholic faith were the primary reasons for women’s resistance to birth control. During the past 20 years, however, the percentage of individuals identified as Roman Catholic have declined, but the percentage of females consistently using birth control has not increased at the same rate. The reality is that in Nicaragua, there are other factors besides religion that have a significant impact on the willingness and ability of women to use contraceptives.

Education and Information

One of the key factors in terms of use of contraceptives is information and education. Most men and women have an understanding of birth control, but their knowledge is confounded by myths and misinformation. There is no consistent and mandated education on reproduction in the school systems, and many girls find out about sexual health via friends and family (Meuwissen et al. 2006a, d). This leads to disparities in the content and consistency of information regarding reproduction and sexual health. Women in rural areas, for example, are more likely to forego contraception altogether (Zelaya et al. 1996). Women of low socioeconomic status in rural areas had a rate of contraceptive use of 69 % as compared with 93 % of women in urban areas (Zelaya et al. 1996). In one remote area of Matagalpa, for example, women of childbearing age indicated that they knew about birth control pills but were afraid to use them in fear of contracting cancer. Myths and misinformation, however, are not just limited to non-professionals. Doctors, for example, have been reported to recommend the rhythm method, warned women about the dangers of birth control pills, and suggested that condom use was not effective and potentially cancerous (Meuwissen et al. 2006a, d).

Gender Issues

Some women choose to practice birth control methods that do not involve their partners in the decision-making process. This may be due to the fact that there is still a sense of machismo throughout the country in which men do not see the value or necessity of engaging in protection. As part of this culture is the belief that a man proves his virility and manliness by fathering multiple children (Lion et al. 2009). There is no corresponding expectation that men will be financially or socially responsible for these children, and there is an increase in consensual partnerships which provide no legal protection in terms of responsibilities of fathers. The burden of protection therefore falls on the women. In a study in León, the most prevalent form of birth control in women aged 15–49 was sterilization (39 %), followed by intrauterine device (16 %) and birth control pills (13 %) (Zelaya et al. 1996). Men in urban areas (78 %) were more likely to engage in the decision-making process regarding birth control than men in rural areas (57 %) with the most prevalent forms of contraception being sterilization, oral contraceptives, condoms, and IUDs (Zelaya et al. 1996). Men of higher socioeconomic status are also more likely to use condoms than men from backgrounds of poverty (Zelaya et al. 1996). Most men and women report dislike of birth control methods as the main reason for not consistently engaging in prevention.

Sex education and teenage pregnancy prevention programs are minimal as well. The Ministry of Health (MINSA) recognizes adolescent pregnancy as a significant factor in Nicaragua, but there are no consistent and integrated plans to address the issue nationwide. There is no reproductive health program in the school system nor is there any national plan to raise awareness on ways to prevent teenage pregnancy. Surprisingly, however, 70 % of all sexually active women between the ages 15–24 reported using contraceptives at least once (Lion et al. 2009).

Methods of Birth Control

Adolescents in Nicaragua are engaging and experimenting with sexual practices. Data analysis of the 2001 Nicaragua Demographic and Health Survey results showed 35 % of girls aged 15–19 had at least one experience with sexual intercourse. The most common age of first sexual intercourse was 15 years. The average age of first sexual activity was 18.9 years, and the average age of first birth was 19.6 years, showing that the amount of time between sexual debut and pregnancy was limited (Lion et al. 2009). Early age of first sexual experience was a strong predictor of early age of first pregnancy. These results confirm data on the limited use of contraceptives among adolescents. Of the sexually active respondents, more lived in rural areas than urban areas and had not attended secondary school (Lion et al. 2009). Most of the adolescent women knew about contraceptives (96 %), but only a handful of the respondents were aware of their own reproductive cycle and health (Lion et al. 2009). Only 66 % of all respondents aged 15–19 had used a modern form of birth control, and less than half were currently using contraceptives. The most preferred method was DepoProvera. Only 1.9 % of adolescents used condoms, which is problematic in terms of the rise of STIs and HIV in Nicaragua (ENDESA 2006). The majority of young women who did not want to get pregnant but were not using contraception justified their behavior based on the fact that they were not cohabiting or involved in a serious union and/or did not have frequent sex (Lion et al. 2009). The results suggest that young women in marriage or domestic unions were more likely to practice family planning and delay the onset of their first child.

There are also distinct differences between adolescents in rural and urban areas. Girls in urban areas were more likely to have engaged in sex at an earlier age and entered into a first union (Samarandi and Speizer 2010). This may be explained by less traditional values and more sexual experimentation among women in metropolitan areas. The results, however, may be skewed by underreporting of sexual behavior among adolescents in rural areas. Women in urban areas were more likely to practice family planning methods than women in rural areas (Lion et al. 2009). The most recent National Demographic and Health Survey found that 31.4 % of adolescents in rural areas were either pregnant or mothers as compared with only 20.1 % in urban areas (INDIE 2006). This may be due to the prevalence of information and resources in urban areas that make it easier for adolescents to gain access to modern forms of contraception.

Birth control methods among Nicaraguan women are sporadic and inconsistent. Approximately 75 % of the population aged 15–49 report using birth control although there are disparities between urban and rural areas. The most common form of contraception is sterilization (25 %) followed by injections (23 %), and only 4 % of the population relies on condoms (INDIE 2006). The segment of the population least likely to use protection is that of adolescents aged 15–19, with only 61 % relying on birth control (INDIE 2006). Results from the 2001 Nicaragua Demographic and Health Survey indicated that only 3 % of women between the ages of 15–49 reported using condoms (WHO 2008). In 2001, the Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Census (INEC) and Ministerio de Salud (MINSA) reported a slightly higher rate of 7 % among females aged 15–19. This same study found that only 47 % of sexually active female adolescents used a birth control method other than condoms (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Census [INEC] and MINSA 2002). These results present a significant problem as adolescents, in general, are more likely to engage in sporadic sex with multiple partners and are less likely to use continuous birth control methods such as oral contraceptives or injections (Lion et al. 2009). The issue is even more pronounced in rural areas where adolescents do not have continuous access to birth control methods. Because of this fact, teenagers may rely on natural reproductive cycles. Women are aware of contraceptives but are inconsistent in their use of these methods, thus leading to high rates of adolescent fertility.

Violence and Partner Violence

Another area of concern when exploring the issue of adolescents and reproduction is violence. Violence against women is, according to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a human rights issue. Partner violence is higher among pregnant women and increases risk of miscarriage, preterm delivery, and infant mortality (Valladeres et al. 2005). In Nicaragua, partner violence is high and often associated with pregnancy. Between the years 2005 and 2007, some 1,247 girls and women reported being victims of rape or incest (Amnesty International 2010). Of these cases, 198 ended up pregnant. Of these, 172 were girls between the ages of 10–17 (Amnesty International 2010).

The World Health Organization has designed a Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Life Events which includes items on emotional, physical, and sexual violence (García-Moreno et al. 2005). A secondary data analysis of the study reported that 32 % of respondents suffered from violence during pregnancy, and 17 % of those experiencing abuse had suffered it from a combination of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse (Valladeres et al. 2005). Of the respondents reporting violence, 26 % had never experienced violence before pregnancy. Those who had experienced violence in their past reported more frequent and intense violence during the pregnancy. This shows that pregnancy itself is a risk factor in terms of partner violence (Valladeres et al. 2008).

Younger women report more violence during pregnancy than older women in Nicaragua. Women who were abused were also less likely to have a planned pregnancy (Valladeres et al. 2005). This is significant when exploring the use of contraceptives among adolescents and rates of teenage pregnancies. Both unwanted pregnancies and young age are associated with violence among pregnant adolescents. The perpetrators were often jealous, angry over refusal to engage in sexual practices, or blamed partner disobedience for the reasons that they initiated violence. Alcohol and substance abuse were also leading factors of violence (Valladeres et al. 2005).

Violence also has an impact on maternal and child health. Pregnant women who were abused were less likely to seek prenatal health care. Pregnant women suffer from severe forms of violence including punches and kicks in the abdomen. Over 60 % of all respondents who were abused reported repetitive acts of violence, but only 14 % actually sought medical attention for the damage. Consequences of not seeking medical care included internal bleeding and spontaneous abortion (Valladeres et al. 2005). These reports are consistent with reports in other similar countries in Latin America.

Many incidents of violence are unreported in Nicaragua. The culture in Nicaragua is based on the value that families deal with issues internally rather than involving outside law enforcement. Most pregnant women who experienced violence did not contact the police, and over 45 % of respondents had never reported the abuse to anyone (including parents). The majority of respondents (80 %) also reported that family problems, including violence, should be kept within the family, and 45 % stated that even in cases of violence, outsiders should not interfere (Valladeres et al. 2005). Some women who are victims also report that the man is justified in committing violent acts if the woman is unfaithful or disobedient. These responses speak to the distinct traditional and cultural values surrounding gender and power.

Abortion

Associated with violence is the controversy over termination of pregnancies. Nicaragua has one of the strictest abortion laws in the world with a total ban on abortion. Only 3 % of the countries in the world have similar policies (Amnesty International 2010). Until 2006, abortion was legal in Nicaragua when the health and life of the mother was in danger. The decision to carry through with an abortion was made through a panel of four medical professionals who could speak about the health and safety of the mother. In 2006, however, the National Assembly of Nicaragua enacted and the president signed a total ban of abortion in Nicaragua, including a repeal of Article 165 of the Penal Code which had allowed for therapeutic abortion (Asamblea Nacional de la República de Nicaragua 2006). This ban includes any form of medical attention to pregnant girls and women that may endanger the life of the fetus, including treatment for cancer, HIV/AIDS, malaria, or cardiac emergencies. The law also makes no distinction between abortion and miscarriage, thus potentially violating the human rights of women who experience a miscarriage through no fault of their own. Finally, the law criminalizes medical practitioners who provide any treatment to pregnant females that endanger the life of the unborn child.

The repeal of Article 165 was enacted despite opposition from Nicaragua’s Ministry of Health which advocated upholding the legality of “therapeutic abortions” in the specific events when the life of the mother was in danger. Repeal of this law has affected a number of girls and women who became pregnant due to rape or incest. In a recent case, a 10 week pregnant mother, age 27, who suffered from cancer that had spread to her breasts, lungs, and brain was denied chemotherapy because the treatment might harm the unborn child (Carroll 2010). Amnesty International’s Executive Deputy Secretary, Karen Gilmore, has also voiced opposition to Nicaragua’s new abortion laws, by saying “Nicaragua’s ban on therapeutic abortion is a disgrace. It is a human rights scandal that ridicules medical science and distorts the law into a weapon against the provision of essential medical care to pregnant girls and women” (Amnesty International 2010). Since the total ban on abortion was enacted, maternal deaths have increased. There has also been an increase in pregnant teenagers committing suicide (Maloney 2009).

Pregnancy and Childbirth

Pregnancy can be a serious and sometimes fatal situation for adolescents. Pregnancy and childbirth are the leading causes of death among girls aged 15–19 in developing countries (Reynolds et al. 2006). The reasons for this include poor maternal and child health care practices. Young women from developing countries are less likely to know about reproductive health and prenatal care than older women from developed nations. Younger women are also less likely to access child health and immunizations services. The risk of death is 2–4 times as high for pregnant mothers under the age of 18 as compared to women aged 20 and older. Furthermore, the risk of infant mortality of babies born to mothers under the age of 20 is 34 % higher due to low birth weight. Children under the age of five born to an adolescent mother have a 26 % higher risk of death (Reynolds et al. 2006).

Adolescents who are pregnant are more likely to be from poor, rural, and traditional backgrounds. This applies to Nicaragua as well and leads to inconsistencies in terms of reproductive health care. The World Health Organization defines prenatal care as the experience of seeing a skilled healthcare provider at least once during a pregnancy (Reynolds et al. 2006). Prenatal care is significant in which health care professionals can detect women at high risk for medical complications and provide the intervention needed to increase high-quality maternal and child health. In Nicaragua, pregnant adolescents under the age of 18 were less likely to take advantage of prenatal care than older adolescents (Reynolds et al. 2006). This may, in part, be due to socioeconomic factors that limit access to prenatal care. Pregnant teenagers may also be less informed about the importance of prenatal care and the options available to them. Finally, there is the issue of stigma attached to being young, pregnant, and unmarried. For women in traditional communities, this stigma may deter desire to seek prenatal care.

The health risks continue to be a factor after delivery. Data show that children born to teenage mothers are at a greater risk of health issues. One of the greatest concerns is childhood immunizations. Although Nicaragua, through the Ministry of Health, has a nationwide and systematic immunization plan, children from young mothers are at a greater risk of not being immunized. Most teenage mothers followed through with the first round of immunizations but were less likely to follow through with subsequent preventative vaccinations. Children born to young mothers were less likely to have received immunizations for measles and the third DPT. Some of the reasons for this include teenage mothers’ lack of understanding and awareness of the benefits of immunizations and the necessity to follow through with those vaccines that are part of a long-term series. Other reasons include the inability of women in rural areas to follow through with immunizations due to the difficulties and high costs associated with transportation. Finally, the social status and limited decision-making power of teenage girls deter them from making informed choices regarding their health and the health of their children. These decisions may be left to older female relatives, thus diluting the self determination of adolescent mothers. Children born to adolescent mothers are at an increased risk of developing illnesses and disease. Education and access to resources are both needed to reduce this disparity.

Policy and Reproductive Health Care in Nicaragua

Conservative and Religious Backlash

Policies and programs designed to promote gender rights and equality in Nicaragua were successful and prevalent until 2006. Until 2011, Nicaragua had a progressive approach to sexual and reproductive health, which was favorable to reducing teenage pregnancies and promoting family planning. The trend turned with the National Assembly repealing Article 165 of the Penal Code, thus effectively banning all forms of abortion, including those in which the life of the mother is in danger. In 2008, the climate for programs promoting sexual and reproductive health of women became more unfavorable due to contentious municipal elections in which the Sandinistas won despite protests of fraud and corruption from women’s organizations and NGOs. The result has been a decline in international aid and support for Nicaragua for those most in need of health care services.

The decline in health care services for women has been coupled with an increase in the government’s alliance with the Roman Catholic Church. As early as 2003, the church condemned the Manual on Sexual Education which was hence censored by the Nicaragua government (Bendaña et al. 2003). The church has backed the total ban on abortion and even pushed back against programs designed to promote family planning. In 2008, two clinics run by ProFamilia, the Nicaraguan partner organization of the International Planned Pregnancy Federation, were shut down in the interior of the country.

Government Initiatives

Despite the controversy surrounding the 2008 elections and subsequent withdrawal of support from NGOs, Nicaragua continues to be committed to family planning. The National Development Plan of 2005 includes provisions for increasing family planning services and reduction in teenage pregnancies among married couples (Indacochea and Leahy 2009). In addition, the National Health Plan for 2004–2015 calls for a complete end to the unmet need of contraceptives, thus solidifying support for family planning. The 2008 Short-Term Institutional Plan Aimed at Results targets the health of women, children, and individual autonomous regions of Nicaragua. This plan calls for programs to increase family planning services for women of fertile age with a high priority on adolescents (Indacochea and Leahy 2009). The priority is on family planning, prenatal care, delivery services, and postnatal care.

International and Non-governmental Organizations

There are other programs designed to provide prevention and intervention in reproductive health. Project resource mobilization and awareness (Project RMA) has partnered with Population Action International, the German Foundation for World Population, and the International Planned Parenthood Federation to increase “tangible financial and political commitment to sustainable reproductive health supplies through international coordination and support of national advocacy strategy development and implementation in developing countries” (Idanocochea and Leahy 2009). Project RMA works closely with Nicaragua to coordinate and supply contraceptives and to integrate national policies which provide for sustainable funding for contraceptives and family planning.

National Plan on Sexual and Reproductive Health

One important document in examining the development of future policies and programs related to adolescent health is the 2008 National Plan on Sexual and Reproductive Health (MINSA 2008). This plan, developed by the Nicaraguan Ministry of Health, emphasizes the need for sex education among adolescents (MINSA 2008). This plan calls for improved quality and access to sexual and reproductive education for adolescents. In order to achieve this goal, the health ministry calls for collective responsibility from multiple government agencies including the Ministry of Education, Institute of Social Security, institutions of higher education, and NGOs. The plan calls for the following (MINSA 2008):

-

1.

formal education,

-

2.

informal education,

-

3.

cultural awareness and promotion of contraception,

-

4.

adolescent-friendly health services with attention paid to culture, gender, and generation.

This comprehensive plan demonstrates the willingness of the Nicaraguan government to support programs designed to reduce teenage pregnancy and highlights the priority placed on collaborative efforts of governmental, non-governmental, and international organizations to achieve this goal.

Competitive Voucher Programs and Adolescent Health

There are several health care and prevention programs designed to target high-risk populations in Nicaraguan. Some are funded through the Ministry of Health, and others are conducted in partnership with international organizations. The Central American Health Institute of Nicaragua (ICAS) is one example of a non-governmental organization designed to reduce the number of teenage pregnancies in Nicaragua (Instituto Centroamericano de Salud [ICAS] 2010). The ICAS has received funding from the Ministries of Foreign Affairs of the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and the United States to establish a competitive voucher program in Nicaragua. This program is designed to empower adolescents to take control of their sexual and reproductive health through free medical consultation.

The voucher program is based on the theory that health care delivery in free markets leads to disparities in treatment. Those with the greatest access to wealth are at greater liberty to pick and choose effective and high-quality health care. Those at the bottom of the socioeconomic scale do not have these same privileges and oftentimes receive medical attention that is limited and is of low quality. These disparities, however, are not just limited to the individual’s health and well-being but impact the society at large because unwillingness or inability to access public health care and prevent disease leads to long-term, macro health consequences (for example in the spread of sexually transmitted diseases, HIV/AIDS, unwanted pregnancies, and childhood illnesses). Furthermore, a healthy society is beneficial to a nation, and in particular a developing nation, through productive work forces (Borghi et al. 2003).

Competitive voucher programs have been pilot-tested in several countries and backed by the World Bank as an effective strategy in enhancing health care access and delivery in developing nations. While many of these nations have put into place programs and clinics to address issues related to sexual and reproductive health, the reality is that some countries, because of social and economic limitations, are not able to provide consistent, high-quality care. The competitive voucher program expands health care options by contracting not only with public entities but also with private and non-governmental clinics. Individuals, and in the case of Nicaragua adolescents, are then given the freedom and autonomy to decide which clinic or agency is right for him or her (Gorter et al. 2003).

The competitive voucher programs in Nicaragua include HIV/AIDS and STI prevention programs, cervical cancer prevention, and promotion of sexual and reproductive health of adolescents. Targeted population includes adolescents between the ages of 12 and 20 in the departments of Managua, Rivas, and Chinandega (Gorter et al. 2003). Vouchers are distributed through the ICAS and 15 other NGOs in the surrounding area. Vouchers have been distributed in neighborhoods, parks, sporting arenas, adolescent clubs, and schools (ICAS 2010). Through the vouchers, teenagers receive free access to medical consultation and follow-up at any of the 20 clinics and agencies contracting with the program. Adolescents can make their own decisions about where to receive health care rather than relying on social and economic mandates. Adolescents participating in the voucher program received sexual health education classes, condoms, counseling, treatment for HIV/STIs, and when needed, prenatal care. The purpose of this voucher program is to increase prevention of HIV, STIs, and unwanted pregnancies and empower adolescents to take charge of their health (Gorter et al. 2003).

In addition to provision of medical treatment, the voucher program established a public awareness campaign in 2004. This campaign is targeted at rural and underserved areas of Nicaragua where adolescents may lack or have misinformation on sexual and reproductive health. This campaign focuses on methods of communication familiar to adolescents such as peer training, entertainment and recreational venues, mass media, life skills, and community action (ICAS 2005). The design of this campaign is based on similar designs in other developing countries.

ICAS has submitted a proposal to expand the voucher program from individual-specific primary care and public awareness campaigns to communitywide initiatives designed to push back against adolescent pregnancy. If funded, this proposal would empower communities to become more active in preventing adolescent pregnancy and providing support for teenage mothers. The concept behind the proposals is that adolescent sexual and reproductive health is not only a micro issue but also a macro issue and that, in a sense, it does take a village to raise and protect a child. Community members will be trained as lay health promoters, and public campaigns will be designed to identify and bolster the role of communities in prevention and care of adolescent pregnancies (ICAS 2005). This proposal also takes into the account the role and responsibility of men for their own sexual health and the subsequent health of the community (ICAS 2005). The community empowerment model is designed to mobilize entire communities in changing norms and expectations related to gender roles, sexual health, and reproduction. The model also focuses on the community’s role as a change agent through lobbying, advocacy, and policy design.

Recommendations

One of the most favorable factors in addressing the issue of teenage pregnancy in Nicaragua has been the support of the government. Through policies and programs, the government has been committed to reducing the rate of adolescent pregnancy and increasing family planning as a whole nationwide. The work of the Ministry of Health in terms of promoting sex education and providing contraceptives has been critical for the country as a whole. MINSA’s Sexual Health and Reproductive Plan is especially notable in its dedication to increasing access and availability of contraceptives. The plan is also significant in which it targets not only females but males as well and is dedicated to changing cultural and gender attitudes toward contraception. The inclusion of men in this plan is critical to the long-term success and sustainability of family planning initiatives. Future policies must continue to involve the Ministry of Health and local health clinics administered through SILAIS. These agencies are committed to family planning and have established local health centers which are crucial to the sustainability of health initiatives.

The Nicaraguan government has demonstrated a willingness to work with NGOs and international agencies. This welcoming environment should prove helpful in increasing and expanding programs dedicated to adolescent sexual and reproductive health. Regardless of political party, there has been no indication that Nicaragua will continue to be anything but supportive and welcoming of outsider intervention. One of the challenges of private funding and NGOs is to not duplicate services. This means that international agencies must be willing to work together despite historical and political relationships. The Internet is especially useful in developing international partnerships and collaborative efforts and should be an excellent venue for coordination of services.

The competitive voucher program has had success, especially in the areas of providing free, confidential consultation for adolescents, and in providing training for healthcare professionals on the benefits and limitations of contraceptives. There is evidence that the training is only as successful as the length of the voucher program, and once contractual services ended, health care professionals tended to promoting more traditional forms of birth control such as the natural rhythm method. Other medical providers continue to provide misinformation regarding oral contraceptives, and male doctors are more likely to dissuade adolescents from using condoms. This evidence suggests the need for more training and longer sustainability of the voucher program in order for a more sustained change in cultural attitudes toward contraception from healthcare professionals. In addition, the voucher program has been limited to specific areas of Nicaragua. An expansion of the program to other areas would be beneficial.

One area that has received limited attention and support services is the Atlantic region of Nicaragua. The northern and southern autonomous regions (RAAN and RAAS) are the poorest and most underserved areas in Nicaragua. Transportation to and communication within these regions are limited. Cultural and language differences within the indigenous and English Creole populations may mean that plans that work well on the western side of Nicaragua may not automatically transfer to the eastern seaboard. These two regions have higher rates of people who are living in poverty, unemployed, and illiterate. These areas also have higher rates of teenage pregnancies and lower rates of usage of contraception. Adolescents in RAAN and RAAS are also at a higher risk of drug addictions, STIs, and HIV partly due to drug trade along the coast. Continued and expanded healthcare coverage and support for all individuals, including adolescents, is critical. This should include awareness on the dangers of contracting sexually transmitted infections and HIV.

Conclusion

During the revolutionary period in Nicaragua, one of the many slogans was “Patria Libre o Morir” which essentially meant that those fighting for freedom would never give up—not until death. In many ways, this slogan represents the spirit of Nicaragua in the past, present, and future. The Nicaraguan people are loyal, genuine, and dedicated. Their fighting spirit of the past is evident in their present drive to press forward in current times, despite economic hardship, political unrest, and natural disaster. This energy and hope is manifested as well in the policies within the country designed to provide a better future in terms of social, educational, and health conditions.

The good news for those interested in medical, health, and psychosocial issues is that Nicaragua is a country with a rich history of working toward social change and embracing external assistance from other countries, NGOs, and individual volunteers. The challenge for those genuinely interested in providing help is to keep in mind that while Nicaragua may be labeled as a “developing nation,” the reality is that the country and her citizens are bright and engaged in the world around them. Those working in human services are knowledgeable about the world around them, informed on current public health issues, and highly trained on current medical practices. What the country needs, as evident through the data on resources and provisions, is consistent and sustainable access to health care, health education, and contraceptives.

Policies and programs designed to address adolescent pregnancy in Nicaragua must continue to provide outreach to the largest and fastest growing population in the country—the youth. Strategies must include creative ways to reach teenagers in rural areas, those living in urban poverty, and those living in the remote region along the Atlantic Coast. These methods will need to continue to incorporate lay health workers along with plans on how to bring sustainable aid in the form of contraceptives to remote areas. These efforts must also include programs that address the serious link between drug and alcohol consumption and unwanted pregnancies, and risk of STIs. International development workers should also consider ways to incorporate technology into these efforts. While the digital divide is a reality in Nicaragua, as elsewhere, there are plenty of youth and young adults in the country who are now communicating via cell phones, texting, e-mail, and online social networks. A simple search through the Ministry of Health will demonstrate the wide range of educational materials online. What is encouraging about Nicaragua is that conversations on sexual and reproductive health are not taboo and are openly discussed in many families and communities. Billboards, television, and radio announcements with messages on teenage pregnancy prevention and HIV/AIDS awareness are prevalent. Most health clinics will provide information on family planning. Even the Ministry of Education is committed to designing programs around adolescent reproductive health. Despite a sagging economy and decrease in foreign aid, the country continues to press forward in its quest toward more progressive and proactive solutions to social problems. The Nicaraguan people are most definitely resilient.

References

Amnesty International. (2010). Listen to their voices and act: Stop the rape and sexual abuse of girls in Nicaragua. Report prepared for Amnesty International. London, United Kingdom. Retrieved from http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/AMR43/008/2010/en/9eaf7298-e3b2-41ae-acdd-f235b5575589/amr430082010en.pdf

Angel-Urdinola, D., Cortez, R., & Tanabe, K. (2008). Equity, access to health care services, and expenditures in health in Nicaragua. Report by the Health, Nutrition, and Population Family of the World Development Network.

Arce, C. (2009). Agricultural insurance in Nicaragua: From concepts to pilots to mainstreaming. Experiential Briefing Note prepared for the World Bank. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTCOMRISMAN/Resources/NicaraguaCaseStudy.pdf

Arnove, R. (1981). The Nicaraguan national literacy campaign of 1980. Comparative Economic Review, 25(2), 244–260.

Arriagada, I. (2002). Changes and inequality in Latin American families. CEPAL Review, 77. Retrieved from http://www.eclac.org/publicaciones/xml/2/19932/lcg2180i-Arriagada.pdf

Asamblea Nacional Constituyente de la República de Nicaragua. (2006). Ley de Derogación al Artículo 165 del Código Penal Vigilente. Normas Jurídicas de Nicaragua, Retrieved from http://www.ccer.org.ni/files/doc/1186699362_Ley_de_Penalizaci%C3%B3n_del_AbortoCB461294.pdf

Bearinger, L., Sieving, R., Ferguson, J., & Sharma, V. (2007). Global perspectives on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents: Patterns, prevention, and potential. The Lancet, 369, 1220–1231.

Bendaña, G., Palacios, M., & Lacayo, M. (2003). Educación para la vida: Manual de educación de la sexualidad. Report for the Ministerio de Educación, Cultura, y Deportes de Nicaragua.

Berglund, S., Liljestrand, J., Marín, M., Salgado, N., & Zelaya, E. (1997). The background of adolescent pregnancies in Nicaragua: A qualitative approach. Social Science and Medicine, 44(1), 1–12.

Betancourt, V. (2007). Los comités para la disponibilidad de insumos anticonceptivos: Su aporte en América Latina y el Caribe. Report for the United States Agency on International Development. Retrieved from http://www.healthpolicyinitiative.com/Publications/Documents/447_1_CS_Committees_Their_Role_in_Latin_America_Spanish_FINAL_acc.pdf

Bicego, G., & Ahmad, O. (1996). Infant and child mortality. Calverton: Macro International.

Borghi, J., Gorter, A., Sandiford, P., & Segura, Z. (2003). The cost-effectiveness of a competitive voucher schemes to reduce sexually transmitted infections in high-risk groups in Nicaragua. The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. doi:10.1093/heapol/czi026.

Brancati, D. (2007). The impact of earthquakes on intrastate conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(5), 715–743.

Campbell, W., Hernández, I., Ceremuga, J., & Farmer, H. (2010). Globalization and free trade agreements: A profile of a Nicaraguan community. Journal of Community Practice, 18(4), 440–457.

Deliver. (2007). Nicaragua: Informe final de país. Report for the United States Agency on International Development. Arlington, VA.

Gorter, A., Sandiford, P., Rojas, Z. & Salvetto, M. (2003). Competitive voucher schemes for health: Background paper. Developed for the Private Sector Advisory Unit for the World Bank. Retrieved from http://www.icas.net/new-icasweb/english/en_pubs.html

Grinevald, C. (2007). Endangered languages of Mexico and Central America. In M. Brenzinger (Ed.), Trends in linguistics: Language diversity endangered (pp. 59–86). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Indacochea, C., & Leahy, P. (2009). A case study of reproductive health supplies in Nicaragua. Report for the Population Action International. Retrieved from http://www.populationaction.org/Publications/Reports/Reproductive_Health_Supplies_in_Six_Countries/Nicaragua.pdf

Instituto Centroamericano de Salud. (2005). Análisis de los resultados de salud sexual y reproductiva para adolescentes: Managua y Chinandega, 2002–2005. Report for the Instituto Centroamericano de Salud. Retrieved from http://www.icas.net/new-icasweb/spanish/es_adolescentes.html

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Census and Ministerio de Salud. (2002). Encuesta Nicaragüense de Demografía y Salud. Report prepared for INEC & MINSA. Managua, Managua. Retrieved from http://www.inide.gob.ni/endesa/resumeninf.pdf

Instituto Nacional de Información de Desarrollo (INDIE). (2006). Encuesta Nicaragüense de Demografía y Salud. Report prepared for INDIE & MINSA. Managua. Retrieved from http://issuu.com/nicaragua.nutrinet.org/docs/informe_preliminar_endesa_2006–2007

International Labour Office. (2007). Nicaragua: Child labour data country brief. Report prepared for the International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/ipecinfo/product/viewProduct.do?productId=7803

Lau, M., & Flores, G. (2010). Everything is bigger in Texas, including the Latino adolescent pregnancy rate: How do we eliminate the epidemic of Latino teen pregnancy? Journal on Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, 1(1), 1–4.

Lion, K., Prata, N., & Stewart, C. (2009). Adolescent childbearing in Nicaragua: A quantitative assessment of associated factors. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 35(2), 91–96.

Maloney, A. (2009). Abortion ban leads to more maternal deaths in Nicaragua. The Lancet, 374(9691), 677. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61545-2.

Manji, A., Peña, R., & Dubrow, R. (2007). Sex, condoms, gender roles, and HIV transmission knowledge among adolescents in León, Nicaragua: Implications for HIV prevention. AIDS Care, 19(8), 989–995.

Meuwissen, L., Gorter, A., Kester, A., & Knotternus, A. (2006a). Does a competitive voucher program for adolescents improve the quality of reproductive health care?: A simulated patient study in Nicaragua. BioMedical Central Public Health, 6, 204. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-204.

Meuwissen, L., Gorter, A., & Knotternus, A. (2006b). Impact of accessible sexual and reproductive health care on poor and underserved adolescents in Managua, Nicaragua: A quasi-experimental intervention study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 56.

Meuwissen, L., Gorter, A., & Knotternus, A. (2006c). Perceived quality of reproductive care for girls in a competitive voucher programme: A quasi-experimental intervention study, Managua, Nicaragua. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 18(1), 35–42.

Meuwissen, L., Gorter, A., Segura, Z., Kester, A., & Knottnerus, J. (2006d). Uncovering and responding to needs for sexual and reproductive health care among poor urban female adolescents in Nicaragua. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 11(12), 1858–1867.

Ministerio de Salud. (2001). Salud sexual y reproductiva en Adolescentes y Jóvenes Varones de Nicaragua. Managua: MINSA. Retrieved from http://www.minsa.gob.ni/bns/adolescencia/doc/Salud%20Sexual%20y%20rep.PDF

Ministerio de Salud. (2008). Norma y protocolo de planificación familiar. Managua: MINSA. Retrieved from http://www.minsa.gob.ni/bns/adolescencia/doc/Norma%20y%20Protocolo%20de%20Planificacion%20familiar.pdf

NicaNet. (2007). Hurricane Felix devastates RAAN! Retrieved from http://www.nicanet.org/?p=354

Pittman, S., Feldman, J., Ramírez, N., & Arredondo, S. (2010). Best practices for working with pregnant Latina mothers along the Texas–Mexico border. Professional Development: The International Journal of Continuing Social Work Education, 12(3), 17–28.

Population Council. (2011). Nicaragua-fast facts. Retrieved from http://www.popcouncil.org/countries/nicaragua.asp

Rani, M., Figueroa, M., & Ainsle, R. (2003). The psychological context of young adult sexual behavior in Nicaragua: Looking through the gender lens. International Family Planning Perspectives, 29(4), 174–181.

Reynolds, H., Wong, E., & Tucker, H. (2006). Adolescents’ use of maternal and child health services in developing countries. International Family Planning Perspectives, 32(1), 6–16.

Rowlands, S. (2010). Social predictors of repeat adolescent strategies and focused strategies. Best Practices and Clinical Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 24(5), 605–616.

Samandari, G., & Speizer, I. (2010). Adolescent sexual behavior and reproductive outcomes in Central America: Trends over the past two decades. International Perspectives in Sexual Reproductive Health, 36(1), 26–35. doi:10.1363/ipsrh.36.026.10.

Somoza, A. (1980). Nicaragua traicionada. Appleton: Western Islands.

Sternberg, P. (2000). Challenging machismo: Promoting sexual and reproductive health with Nicaraguan men. Gender and Development, 8(1), 89–99.

United Nations. (2011). Country profile: Nicaragua. World statistics pocketbook: United Nations statistics division. Retrieved from http://data.un.org/CountryProfile.aspx?crName=NICARAGUA

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2010). At a glance: Nicaragua. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/nicaragua_statistics.html

United Nations Development Programme. (2010). Nicaragua. International human development indicators. Retrieved from http://hdrstats.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/NIC.html

United Nations Statistics Division. (2010). Population by religion, sex, and urban/rural residence: Nicaragua. Report by the United Nations Statistics Division. Retrieved from http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?q=by+sex&d=POP&f=tableCode%3A28

United States Department of Labor. (2010) Nicaragua. Report for the Bureau of International Labor Affairs. Retrieved from http://www.dol.gov/ILAB/media/reports/iclp/Advancing1/html/nicaragua.htm

United States Department of State. (2009, February). 2008 Human rights report: Nicaragua. Retrieved from http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2008/wha/119167.htm

Westoff, C. (2003). Trends in marriage and early childbearing in developing countries. DHS comparative reports No. 5. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro. Retrieved from http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pub_details.cfm?ID=413#dfiles

World Bank. (2009). Nicaragua: Supporting progress in Latin America’s second-poorest country. Nicaragua country profile. Retrieved from: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/LACEXT/NICARAGUAEXTN/0,,contentMDK:20214837~pagePK:141137~piPK:141127~theSitePK:258689,00.html

Zelaya, E., Peña, R., García, J., Berglund, S., Persson, L., & Liljestrand, J. (1996). Contraceptive patterns among women and men in León, Nicaragua. Elsevier Science, 54, 359–365.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Campbell, W., Jenkins, A.E. (2014). Adolescent Pregnancy in Nicaragua: Trends, Policies, and Practices. In: Cherry, A., Dillon, M. (eds) International Handbook of Adolescent Pregnancy. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-8026-7_25

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-8026-7_25

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN: 978-1-4899-8025-0

Online ISBN: 978-1-4899-8026-7

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)