Abstract

This chapter provides a comprehensive overview of acculturation patterns and their psychological correlates among Arab Americans across the lifespan. First, Arab American racial and ethnic identifications are analyzed within the historical context of three waves of immigration to the USA. This history provides a backdrop to the diversity of present-day acculturation orientations, which are influenced by factors such as generation status, length of residence in the USA, religion, and discrimination. The chapter reviews the mental health correlates of these acculturation orientations, as well as protective factors such as family, ethnic identity, and religiosity that have been found to promote resilience and reduce acculturative stress. Unique acculturation experiences are discussed for youth, women, and the elderly. In addition to identifying gaps in the literature, the chapter offers a critique of Arab American acculturation research to date, including limitations in conceptualizations and methodologies. Notwithstanding these limitations, recommendations are offered for using existing and future research to inform community-based programming.

Even when the language hurdle is overcome and foreign accents are barely discernible; when tastes and manners of the larger society have been imbibed in large drafts; when the Old World customs are scorned as visible tags of foreignness or hindrances not only to acceptance in American society but to feeling—to being—American; and even when, many native values are, no matter how reluctantly, compromised or dropped, assimilation need not have been achieved. It is a continuous process in the lifetime of the first generation… whether it can be achieved in the lifetime of the next generation is an open question.

(Naff, 1985, p. 8)

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Arab American

- acculturation

- ethnic identity

- immigration

- acculturation stress

- risk and protective factors

- gender roles

- identity development

- psychological wellbeing

- community intervention

Arabs in America are situated within a remarkably unique combination of paradoxes that affect their cultural identities and attachment to American society. They are racially categorized as “White” although their skin colors can vary across the spectrum and they are perceived by others to be “not quite White” (Samhan, 1999). Whereas their legal classification places them alongside the majority, they experience life in the USA as a minority group, including forced marginalization and discrimination. Although these contradictions render them an invisible minority (Naber, 2000), they have gained increasing visibility especially in the post-9/11Footnote 1 sociopolitical world. In this decade after 9/11, the stereotypes regarding Arabs have grown overly simplified and conflated with “Muslim,” although during this same period the Arab American community increased significantly in diversity of national origin, histories, reasons for immigrating, socioeconomic factors, and acculturation patterns.

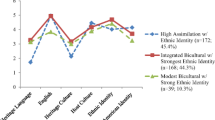

Perhaps the most compelling acculturation paradox is that as an immigrant minority group, Arabs in America have the task of adapting to the host “White” culture, of which they are already classified as being members! Yet the White classification is in itself a historical point of contention for Arab people in the USA. This chapter traces these historical roots as well as contemporary acculturation patterns among Arabs living in the USA. There is a particular focus on sociodemographic factors that contribute to higher Arab ethnic immersion and increased adoption of American culture, as well as how these acculturation indicators in turn influence psychological well-being. Many of the findings in the research literature are illustrated in Fig. 8.1. These patterns may differ across the lifespan, and as such the chapter includes a focus on the experiences of youth and elderly, as well as how traditional gender roles are interwoven in Arab American culture. Finally, previous literature is critiqued with an eye for future research and community programming that can facilitate the immigration and acculturation of Arab Americans.

History of Arab Acculturation to America

Arab immigration to the USA occurred in three phases, each characterized with distinct strategies of adapting to American society. The first phase took place from the late 1800s to World War II, with most immigrants coming from Greater Syria (now, Syria and Lebanon). The majority of these immigrants were Christians who voluntarily immigrated seeking economic betterment (Naff, 1985). They worked as farmers, peddlers, and small store owners (Suleiman, 1999) and were typically uneducated and spoke little English (Samhan, 1987). These early Arabs perceived their residence in America to be a temporary state and thus continued to maintain primary allegiance to their homeland in terms of language, customs, and even political affiliations (Naff, 1985; Suleiman, 1999). Their identity was more deeply attached to their family lineage, religious sect, or home village, rather than the American community or a pan-Arab identity that had not yet emerged (Samhan, 1987; Suleiman, 1999).

The early settlers were relatively separated from American society, and then during World War I they additionally faced forced isolation from their homeland. This resulted in both a heightened sense of communal solidarity and an increased preference to assimilate in American society (Suleiman, 1999). These early primarily Christian Syrians rapidly assimilated into the educational, economic, political, and cultural landscapes of American life (Samhan, 1987). This process was facilitated by their second-generation children who had already been raised without the linguistic and ethnic traditions of their parents (Naff, 1985; Suleiman, 1999). By World War II, many of the early settlers and their children had successfully melted into the fabric of American society (Naff, 1985; Suleiman, 1999).

Arab immigration was constricted in the first half of the twentieth century due to the two World Wars as well as shifting immigration policies and a quota system that favored Northern Europeans (Samhan, 1987, 1999; Suleiman, 1999). After World War II, the Arabs who arrived to America brought with them higher levels of nationalism and Arab ethnic pride compared to their predecessors. Heightened Arab identity corresponded with the independence of Arab nations from colonial powers and the growth of a nationalistic and pan-Arab movement in the mid-1900s (Naff, 1985; Samhan, 1987). This second wave of immigrants included a higher proportion of women, young adults, Muslims, and Palestinian refugees displaced by the establishment of Israel in 1948 (Naber, 2000).

Subsequently, a third wave of immigration began in the 1960s in response to less restrictive immigration policies. Unlike the previous waves, these new immigrants were more diverse in national origin, the majority coming from Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Egypt, and Iraq (Samhan, 1999). More recently the USA has seen immigrants from Yemen, Somalia, Gulf countries, and North Africa. Although many in the third wave came voluntarily for educational and economic opportunities (Wrobel, Farrag, & Hymes, 2009), significant numbers arrived fleeing wars, sectarian violence, and religious persecution, including significant populations of refugees. The majority were Muslims for whom religion was an important component of their ethnic identity (Suleiman, 1999).

The more recent communities of Arabs comprising the third wave are more keen to maintain their ethnic and religious traditions, are more nationalistic, and are more vocal in their disapproval of US foreign policy (Naber, 2000), thereby showing less assimilation than their predecessors (Samhan, 1999). Some are even culturally isolated in their own ethnic and religious communities with minimal interaction with the larger society (Shain, 1996). These trends towards cultural marginalization were further reinforced by America’s stalwart support for Israel—and thus against Arab nations—in the 1967 war. Such foreign policies kindled prejudice and hostility towards Arabs (Naber, 2000; Shain, 1996). Parallel to these trends was the cultivation and politicization of a distinct pan-Arab “Arab American” identity to which the Arab community showed increasingly strong allegiance (Naber, 2000; Shain, 1996).

Throughout the history of Arab immigration and adaptation to American society, a controversial question regarding their racial identity has repeatedly emerged (Samhan, 1999). During the first 30 years of their presence in significant numbers, persons from Syria were assumed to be White; however, the government often classified them as “Turks” because their homeland was under rule of the Ottoman Empire (Suleiman, 1999). The American public also showed confusion regarding these immigrants, referring to them as Turks, Armenians, Assyrians, and Arabians (Naff, 1985). In the early 1900s, public opinion became increasingly antagonistic towards Syrians and other persons who were perceived to be almost-White such as Italians and Greeks. At that time the government declared that Syrians were classified as “Asian” or from “Turkey in Asia.” In one case a judge conceded that Syrians were Caucasian but decided that they were not White (i.e., European) enough to meet the benchmark for citizenship. As such they were denied naturalization and citizenship rights. Subsequently these immigrants launched a series of petitions to be considered for citizenship with arguments about their Caucasian roots and close relation to Europeans; the government continued to respond with contradictory and unclear assessments of these immigrants’ racial status (Samhan, 1999; Suleiman, 1999).

Currently the US government designates peoples from Middle Eastern and North African origin in the categories of White or Caucasian (Naber, 2000). However, there are diverse preferences among Arab communities regarding their identification with different racial statuses (Ajrouch & Jamal, 2007). Some feel protected by the “White” classification, some advocate for a special ethnic status such as “Hispanic,” others prefer to be viewed as a minority of color, some select the “Other” status, and still others prefer to be identified specifically as “Arab” or “Middle Eastern” (Naber, 2000; Samhan, 1999; Suleiman, 1999). Arab Americans who do not identify with the “White” category tend to be recent immigrants, Muslims, and those who endorse their “Arab American” identity (Ajrouch & Jamal, 2007). These diverse racial/ethnic identities illustrate the heterogeneity of the Arab community and their diverse acculturation patterns.

Acculturation Theory and Research Findings

Acculturation as discussed in this chapter refers to the process of adapting to a dominant host culture that differs from the ethnic or national culture of origin. During this process immigrants and their descendants are challenged with the task of negotiating aspects of both cultures while developing a coherent sense of self. There are several theoretical models of acculturation, each with underlying assumptions regarding which acculturation strategies are more advantageous to psychological well-being. These models focus on psychological acculturation, or the individual-level adaptation process, rather than a sociological view of group acculturation. Researchers have built upon these theoretical frameworks when studying factors associated with different acculturation orientations among Arab Americans.

Models of Acculturation

Early approaches to studying acculturation focused on the assimilation model, which proposed that as immigrants adapt to a new host culture, they are increasingly internalizing characteristics of the host culture while simultaneously shedding aspects of their culture of origin (Castro, 2003; Richardson, 1967). According to Richardson (1967), for assimilation to occur, immigrants need to first experience satisfaction with the host culture, next begin to identify with it, and then they “acculturate,” or gradually approximate the attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of those from the host culture. An assumption of this linear model was that increased assimilation corresponded with positive adaptation (Rumbaut, 1997).

Over time theorists began to question the validity of the unidirectional linear model and its underlying premise that the traditional culture decreases in an inverse relationship to the host culture (Rumbaut, 1997). Instead, they argued that both host and traditional cultures fall on separate or orthogonal continuums and any person can demonstrate varying levels of both (Castro, 2003). The term biculturalism, which previously indicated the midpoint on the assimilation continuum (Castro, 2003), now began to refer to significant engagement with both host and traditional cultures under the bidimensional models (Berry, 1997).

Perhaps the most well known of the bidimensional models was proposed by John Berry (1997). He argued that individuals determine the extent to which they will adopt the new host culture and/or maintain the old. Those who gain high immersion in the host culture with low retention of the traditional culture are labeled assimilated. The opposite pattern of maintaining high levels of traditional culture and resisting the adoption of the host culture is called separation or isolation. Some people, however, select the strategy of fostering both the host and traditional cultures, which is called integration. Finally, persons who eschew both the host and traditional cultures experience marginalization.

Previous writers have argued that integration is associated with the most positive psychological adaptation, followed by assimilation and separation, while marginalization is linked with problematic outcomes such as emotional distress and identity confusion (Berry, 1997; Castro, 2003). Positive adaptation is reflected in a clear sense of self, high self-esteem, and good mental health (Castro, 2003). Berry’s conceptual model has come under criticism, with empirical evidence showing inconsistent results regarding the salutary effects of the different acculturation orientations (Rudmin, 2003). As such, many acculturation theorists have found it more useful to focus on acculturation stress as a predictor of psychological adaptation rather than acculturation orientation per se. Acculturation stress refers to significant tensions and demands experienced by the acculturating individual in the process of adapting to the new society, and this construct aligns with stress and coping models (Berry, 1997).

Because acculturation stress emerges in response to frictions between the acculturating individual and his/her new host country, it can be assumed that persons with higher levels of traditional culture identification may face more acculturation stress. This self-identification with the traditional culture is often referred to as ethnic identity and incorporates a sense of emotional attachment and belonging towards the ethnic group, a desire to learn about the ethnicity, and adoption of ethnic values and beliefs (Phinney & Ong, 2007). Adult immigrants arrive with an already developed—although dynamically shifting—sense of ethnic identity that may increase or decrease in strength over time (Phinney & Ong, 2007). However, youth who are raised in the host culture must be socialized into adopting knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of their traditional ethnic culture (Castro, 2003). The process of retaining and nurturing ethnic identity (for immigrants) or socializing into the ethnic culture (for those born in the host country) is called enculturation (Yoon, Langrehr, & Ong, 2011). Enculturation provides a natural mechanism for transmitting the ethnic culture across generations (Castro, 2003).

Ethnic Identity Among Arab Americans

For generations of Arab immigrants to America, religion and family have remained essential components of their Arab ethnic identity. Research shows that religiosity is intricately interwoven in the ethnic consciousness and is used as a benchmark for helping immigrants determine what aspects of American society to adopt or reject. This is so much so that immigrants may make reference to religious issues when asked to discuss ethnic issues (Ajrouch, 1999). In addition to religion, community culture and family are also deeply interconnected with the framework of Arab identity (Beitin & Allen, 2005), with family and social networks serving as the foundation upon which ethnic identity is shaped (Ajrouch, 2000).

For those from the second and later generations, Arab ethnic identity is nurtured primarily in the home environment, which may include extended family members and a neighborhood Arab enclave in some regions of the U.S. Family members, particularly parents, socialize children from a young age to identify with their Arab origins. Some of this enculturation occurs through explicit instruction, whereas a significant portion is through more subtle demonstrations of the Arab culture such as maintenance of the Arab patrilineal system. Purposeful instruction in religiously and culturally acceptable behavioral practices was not necessary in the home country because such behaviors were part of the natural way of life (Ajrouch, 1999). Living in America on the other hand challenges these Arab Americans to negotiate their ethnic and American identities and emerge from the encounters with a cohesive sense of self (Beitin & Allen, 2005). Furthermore, Arab Americans combine both their Arab and American identities in a unique pattern that produces a distinct identity that is different from the original Arab and American cultures (Mango, 2010).

Factors Influencing Arab American Acculturation

Researchers have identified several factors that influence Arab Americans’ acculturation and the relative strength of their ethnic and American identities. One predictive factor is amount of exposure to American culture, as reflected in number of years residing in the USA as well as generational status. Longer length of residence in the USA is associated with greater immersion and identification with American culture (Amer, 2005; Faragallah, Schumm, & Webb, 1997). Likewise, fewer and less frequent visits to the Arab homeland are associated with greater adoption of American culture (Faragallah et al., 1997), whereas more frequent visitations are associated with separation from American society (Amer & Hovey, 2007).

With respect to generational status, children who were born or raised in the USA may find a natural ease in embracing American beliefs and practices compared to their parents, and adult immigrants become increasingly immersed in American culture as their residence continues (Faragallah et al., 1997). Compared to immigrants, second-generation Arab Americans report higher levels of engagement with American culture and lower levels of traditional Arab beliefs, customs, language, and social networks (Amin, 2000; Read, 2004). With each subsequent generation, adoption of American culture increases (Amer, 2005) and maintenance of the traditional culture and language fades (Amer, 2005; Seymour-Jorn, 2004).

Although both common sense and research have shown that amount of exposure to the USA leads to greater adoption of American culture and shedding of Arab ethnic identity, the relationship is more complex as attitudes of individuals can play a role. For example, a study of male Saudi Arabian sojourner university students found that those with more positive attitudes towards Americans were more likely to desire social contact with them and in turn engage in such ongoing contact with Americans (Alreshoud & Koeske, 1997). Similarly, Arab ethnic identity can be nurtured by communities that purposefully teach and transmit the Arabic language, aiming at maintaining the traditional culture and religion, and Arab youth who wish to become closer to their national heritage and Islamic religion may voluntarily choose to enhance their Arabic language skills (Seymour-Jorn, 2004).

Attitudes or perceptions of American culture may be influenced by the extent to which the Arab individuals’ own religious and cultural backgrounds diverge or converge with American culture. One of the key determinants is religion, a fundamental component of Arab collective identity and culture. Both Christian and Muslim Arab Americans use religion as a guidebook for what aspects of American culture to adopt or reject (Eid, 2003; Read, 2004). In that respect, religion is often utilized as a source of strength in withstanding pressures from American society to adopt values and behaviors that contradict ethnic traditions. For instance, a study of Canadian Arab young adults found that religious identity was associated with strength of ethnic identity and traditional gender roles (Eid, 2003).

In addition to religiosity, religious affiliation can itself predict acculturation patterns, with previous literature highlighting differences between Arab Christians and Muslims. Compared to Christians, Muslims tend to score lower on indicators of immersion in American society (Ajrouch & Jamal, 2007; Amer, 2005; Awad, 2010; Faragallah et al., 1997) and higher on indicators of Arab ethnic identity (Amer & Hovey, 2007; Awad, 2010; Faragallah et al., 1997; Marshall & Read, 2003; Read, 2002, 2004). Aside from Arab values and beliefs, indicators of ethnic identity include maintaining Arab friendship networks, participating in ethnic organizations, and marrying within the ethnic group (Read, 2002).

The differences between Christians and Muslims may be conflated with the trend of a large proportion of recent Muslim immigrants who arrived with high levels of Arab nationalism and have had a shorter length of residence in the USA (Marshall & Read, 2003). However, other reasons have been suggested for why Christians report higher adoption of American culture while Muslims report higher ethnic identity. Christians may find the acculturation process less taxing because they share the same religion as the dominant culture (Ajrouch, 2007; Ajrouch & Jamal, 2007; Awad, 2010; Faragallah et al., 1997). They may have also left their nation of origin in search of greater religious freedom or to escape minority status, so positive attitudes towards the new culture facilitate greater American culture immersion (Faragallah et al., 1997). For Muslims on the other hand, acculturation is further compounded by hostile prejudices and discriminatory behavior targeting specifically Islam and Muslims (Ajrouch, 2007); they are more likely to be seen as outsiders (Naber, 2000). As such, Muslims may face more stressors adapting to American culture including discrimination (Amer, 2005; Awad, 2010; Padela & Heisler, 2010).

Discrimination serves as a risk factor in the acculturation process because it can lead to segregation of Arab Americans (Hassouneh & Kulwicki, 2009). Arabs have faced discrimination since their early arrival to the USA, long before 9/11 (Faragallah et al., 1997; Samhan, 1987). In recent years research has documented substantial experiences of discrimination among Arab Americans post 9/11 ranging from ethnic slurs to assaults on self and property (Abu-Ras & Abu-Bader, 2009; Awad, 2010; Beitin & Allen, 2005; Hassouneh & Kulwicki, 2007, 2009; Moradi & Hasan, 2004; Padela & Heisler, 2010). Persons who immigrate at older ages (and thus appear to be more foreign) report more discrimination (Faragalla et al., 1997). Paradoxically, those of the second generation have reported more discrimination compared to the first, which can be attributed to greater level of interactions with the wider American society (Gaudet, Clément, & Deuzeman, 2005). Similarly, higher immersion in American culture can increase opportunities for Muslims to experience discrimination, although their Christian counterparts may face less (Awad, 2010).

Finally, higher socioeconomic status including income and education has been associated with greater adoption of American culture (Amer, 2005). Two studies (Amer, 2005; Amer & Hovey, 2007) found that higher education was associated with less participation in Arab ethnic practices. Education is often associated with language. Facility with the English language is a factor that helps facilitate acculturation to American society and is therefore subsequently associated with positive psychological well-being (Ajrouch, 2007; Beitin & Allen, 2005; Wrobel et al., 2009). A study of Arab American elderly found that English skills were worse for refugees and sojourners compared to those with lengthier or more permanent legal status in the USA (Wrobel et al., 2009). This suggests that language may actually be a proxy for amount of exposure to the USA rather than a factor that directly impacts acculturation and well-being.

Acculturation and Psychological Well-Being

Consistent with acculturation theory, a few studies have found that higher host culture immersion—especially with a bicultural approach—is predictive of better psychosocial well-being among Arab Americans. Greater interaction with American culture (e.g., making American friends) and adoption of American beliefs and practices have been associated with higher satisfaction with US life (Faragallah et al., 1997) and less acculturation stress and depression (Amer, 2005). For example, Arab American couples that made a concerted effort to immerse in American society believed that this strategy helped facilitate their coping with acculturation and post-9/11 stressors (Beitin & Allen, 2005). This pattern was also seen for bicultural individuals who had high levels of both American and Arab identities (Amer, 2005).

On the other hand, and contrary to acculturation theory, some studies have found a strategy of exclusively maintaining traditional Arab ethnic culture to be more predictive of positive psychosocial well-being compared to assimilating or integrating both Arab and American cultures (Amin, 2000). Studies have shown that greater adoption of the host culture is associated with more depression and lower self-esteem (Gaudet et al., 2005) and less family satisfaction (Faragallah et al., 1997). Likewise, Arab Americans with high biculturalism demonstrate lower personal self-esteem (Barry, 2005) and lower personal and emotional adjustment (Amin, 2000). Potential explanations for why Arabs who attempt to integrate or assimilate in American culture report lower psychosocial well-being include greater exposure to prejudice and discriminatory behavior from the host culture and feelings of inferior group status when surrounded by those from the dominant culture (Barry, 2005), as well as cultural and social isolation from their ethnic group (Gaudet et al., 2005).

It is moreover evident that maintaining Arab ethnic identity has salubrious effects on psychological well-being. Arab ethnic identity has been associated with better college adjustment and social adjustment (Amin, 2000), higher collective self-esteem (Barry, 2005), and less acculturation stress (Britto & Amer, 2007). A study by Gaudet et al. (2005) found that higher Lebanese ethnic identity was associated with fewer acculturation daily hassles, which in turn decreased risk for depression which was subsequently related to better self-esteem. Even simply being of Arab ethnic background is associated with positive mental health. For example, in a study in Michigan, per official death records Arab Americans had significantly lower rates of suicide compared to nonethnic Whites. This was hypothesized by the authors to be related to higher ethnic identity, living in an ethnic enclave, religiosity, religious coping, strong community networks, and social support (El-Sayed, Tracy, Scarborough, & Galea, 2011).

Acculturation Stress

In light of contradictory findings regarding acculturation strategies, acculturation stress may be a more sensitive predictor of psychological adjustment. Factors that predict higher acculturation stress for Arab Americans include less competence in English, lower education, involuntary immigration, and shorter length of residence in the USA (Wrobel et al., 2009). In turn, experiences of acculturation stress are linked with psychological distress among Arab Americans (Hassouneh & Kulwicki, 2007) including depression (Amer, 2005; Wrobel et al., 2009). Related to the concept of acculturation stress is that of acculturation daily hassles, which have been found to mediate the relations between acculturation factors (ethnic identity, Canadian identity, discrimination) and mental health (depression and self-esteem) (Gaudet et al., 2005).

Salient acculturation stressors for Arab Americans include discrimination and perceived marginalization from American society, which can increase worries and potential emotional distress (Hassouneh & Kulwicki, 2009) and decrease satisfaction with living in the USA (Faragallah et al., 1997). Post-9/11 backlash in particular has been linked to increased stress and psychological distress (Abu-Ras & Abu-Bader, 2009). For example, a representative survey of 1,016 Arabs and Chaldeans in Michigan found that experiences of discrimination were linked to higher emotional distress and less happiness (Padela & Heisler, 2010). In their study of Arab Americans in Florida, Moradi and Hasan (2004) found a significant association between perceived ethnic–racial discrimination and worsened mental health symptoms, with sense of personal mastery over one’s life partially mediating this relationship. Thus, having a higher sense of personal control served as a protective factor in buffering the stressful consequences of discrimination.

Culturally Embedded Protective Factors

Some protective factors have been found to buffer the stressful acculturation process for Arab Americans. Families, including extended families, form the backbone of the Arab culture and are as such a valued source of social and tangible support (Naber, 2006; Read, 2004). For example, Beitin and Allen (2005) discovered that spousal support served as a resource for resilience for Arab American couples coping with the post-9/11 anti-Arab context. In other studies, Arab Americans who had stronger family support and more cohesive family ties reported lower levels of depression (Abu-Ras & Abu-Bader, 2009; Amer, 2005) and anxiety (Amer, 2005). Immigrant communities that are predominantly professional and have arrived in the absence of chain migration may experience less family support (Keck, 1989). For such isolated nuclear families, friends often assume the roles that extended family would have had back home such as assistance in child-rearing.

Friendships, social networks, and community networks can be sources of support in the acculturation process. Arabs come from communities that value collectivism and interdependence and thus they are accustomed to receiving emotional and tangible supports from others (Abu-Ras & Abu-Bader, 2009). A previous study found that social support was associated with less acculturative stress, less depression, and less anxiety (Amer, 2005). In their study of Arab and Muslim Americans, Abu-Ras and Abu-Bader (2009) documented that availability of community support was related to lower levels of depression and posttraumatic stress and likewise Beitin and Allen (2005) found community support to be a factor in enhancing resilience.

Religiosity has also been proposed as a source of support for Arab Americans, particularly since religion is an important component of the Arab culture. Previous research has found that Arab Americans utilize religious beliefs, supports, and coping strategies to help manage acculturation and post-9/11 stressors (Beitin & Allen, 2005). However, interestingly, other studies have not found religion or religious coping to be associated with acculturation stress or mental health status (Abu-Ras & Abu-Bader, 2009; Amer, Hovey, Fox, & Rezcallah, 2008). Therefore, further research is needed to examine the role of religiosity as a coping strategy for Arab American adults and youth.

Arab American Acculturation Across the Lifespan

Age of immigration and ages at which acculturative stressors are faced can influence acculturation and identity formation. For example, teenage Arab Americans who lived through the post-9/11 backlash may in response have felt marginalized and thus may have developed an identity that eschewed American culture, whereas older Arab Americans may have an already established cultural identity that was somewhat protected from these events (Ajrouch & Jamal, 2007). Even a decade after 9/11 the sociopolitical climate continues to be hostile towards Arabs, thereby continuing to impact the acculturation of Arab American adults and youth.

Youth

The development of an integrated personal identity is a natural developmental challenge for all youth, yet this process is more complicated for Arab youth who are juggling ethnic and American identities. The process is influenced by several external systems, including parents, peers, school, community, and media, each of which can serve as sources of stress or support. For example, Arab youth may face school stressors such as invisibility in the curriculum and antagonism from peers and school personnel (Ayish, 2003). Since 9/11 these types of stressors such as bullying and other forms of discrimination have increased and have led to Arab children feeling marginalized (Britto, 2008). In response, these youth may develop greater attachment to their ethnic identity and ethnic community (Ayish, 2003), which in turn has been linked with higher self-esteem (Mansour, 2000). Arab youth ethnic identity is nurtured by family socialization and the family continues to serve as a primary resource for ethnic identity development (Ajrouch, 2004).

As with adults, religion plays a role in Arab ethnic identity development, particularly in providing guidelines for which behaviors are acceptable (Ajrouch, 2000). Unlike their parents, however, for whom religious creed and rituals are genuinely and deeply interwoven with ethnic identity, among the second-generation religious affiliation is experienced differently. It is instead often utilized as a proxy for ethnic identity even if underlying religious beliefs and rituals are not observed (Eid, 2003). In other words, religion may be used symbolically as a way to define the boundaries of ethnic identity and publicize commitment to the ethnic community, and as such these youth may apply religion in a flexible manner depending on situational contexts.

Previous literature has noted that Arab youth may negotiate and prioritize their religious and cultural identities by using various self-labels such as “Palestinian,” “Arab American,” and “Muslim American” (Christison, 1989). They may also classify or distance themselves from other labels such as “boater” (referring to immigrants with poor English, cultural awkwardness, and lower social status) and “White” (associated with privilege, education, but also excessive freedom and lack of responsibility) (Ajrouch, 2000, 2004). These variations in labels and hyphenated identities continue into adulthood and provide an indicator of their immersion in Arab versus American cultures (Mango, 2010; Read, 2004).

Arab youth are acutely aware of differences between Arab and American cultures, particularly in regard to the acceptability of behavioral practices, and a central task in their development is to negotiate these differences. Perhaps the most striking example is that of dating: having a boyfriend/girlfriend is part of normal development in the USA but is frowned upon by Arab culture and religious values (Ajrouch, 1999). The disparities between ethnic and American cultures are experienced more profoundly for Arab American girls compared to boys. Arab youth perceive Arab girls to be respectful and honorable, while American girls are perceived to be immodest, immoral, but with a desirable independence (Ajrouch, 1999, 2004; Naber, 2006).

As such, gender serves as a focal point with respect to Arab American youth development, with cultural standards differing for boys and girls (Keck, 1989) and boys sometimes receiving preferential treatment (Abudabbeh, 2005). Studies have reported dissatisfaction and complaints from adolescent girls regarding double standards (Ajrouch, 1999, 2004; Keck, 1989). The girls describe restrictions in entertainment, dating, and working that boys do not face; girls often need to return home earlier and face more limitations in places they can visit. Girls experience pressure to conform to ethnic standards of behaviors to preserve the family honor (Ajrouch, 1999, 2004). The brothers themselves are often involved in controlling and chastising their sisters if their sisters’ behaviors transgress in ways that could sully the family reputation; boys are socialized into such behaviors by modeling adult males and parents in the community (Ajrouch, 1999, 2004).

Parent–Child Relationships

Cultural differences between US-born youth and their immigrant parents can result in intergenerational and intercultural conflicts. Parents come from traditional Arab cultures where elders are respected and heeded, the worldview is focused on the past, and stability and conformity are valued. On the other hand the youth are raised in an individualistic, industrialist society in which the worldview emphasizes the future (Ajrouch, 1999). These cultural differences may produce tensions within the youths who are continuously navigating among cultures, as well as between the youth and their parents.

Parents who adhere more strongly to their traditional culture face difficulties in raising their children to meet these cultural guidelines (Christison, 1989). Many Arab American adults parent with an authoritarian style (Abudabbeh, 2005) and use religion as a foundation for cultural instruction (Ajrouch, 1999). Parental involvement may range from selecting Arab friends for their children (Ajrouch, 1999), to censoring sexual content from television and reading materials for their adolescents (Hattar-Pollara & Meleis, 1995), to recommending marriage partners for older youth (Christison, 1989). While Arab American parents may acknowledge the importance of their children’s independence and interactions with American society (Christison, 1989; Read, 2004), the question of where to draw boundaries of what is appropriate presents ongoing challenges. Both parents and children report that as a result of anxieties over potential adoption of culturally unacceptable American practices, some parents may become overly restrictive especially with their daughters or at least may be perceived as such (Ajrouch, 1999; Keck, 1989). The local Arab community may influence this parenting process by collectively contributing to the child-rearing (Keck, 1989) and indirectly monitoring and restricting undesirable behaviors with the use of community gossip (Ajrouch, 2000).

Youth perceptions of their parents’ acculturation and parenting control can moreover affect their psychological well-being. For example, university students who perceived their parents to be more immersed in American culture showed better well-being, particularly if the parents had a more open style of parenting. Parental maintenance of traditional ethnic culture was similarly associated with better well-being for children with less controlling parents (Henry, Stiles, Biran, & Hinkle, 2008). Likewise, a study of Arab American university students found that those who shared a similar acculturation strategy to their own parents demonstrated better psychosocial adjustment (Amin, 2000).

Gender Roles During Adulthood

Child-rearing practices among Arabs in the USA are especially cautious in enforcing traditional gendered codes of conduct throughout adulthood (Eid, 2003). The maintenance of traditional gender roles is a marker of adherence to the collective Arab ethnic identity, and women observe these traditional gender roles as a sign of the family’s ethno-religious identity (Eid, 2003; Read, 2004). The Arab family is generally patrilineal, patriarchal, and hierarchical (Abudabbeh, 2005; Read, 2004). Marriage is valued as a sacred institution, parents and elders are expected to be respected, and the father (or eldest male) has the highest authority (Abudabbeh, 2005). Women are viewed with high status with respect to their child-rearing and domestic functions, while their engagement in the public sphere may be relatively limited or valued less (Read, 2002, 2004). On the other hand, men adopt the primary economic responsibility of the family (Ajrouch, 1999).

Because actions of individual family members can reflect upon the reputation of the whole family (Ajrouch, 1999; Hassouneh & Kulwicki, 2009), serious violations of these gender roles—such as premarital sex among young women—can tarnish the family’s honor and status within the community. In a sense, such violations weaken the barriers with Western culture and thus dilute the purity of the ethno-religious heritage (Eid, 2003; Naber, 2006). Moreover, women themselves are viewed as vehicles for transmitting ethnic beliefs and traditions to subsequent generations and for ensuring that these beliefs and traditions are maintained and nurtured in the family context (Eid, 2003; Read, 2004).

On the other hand, some authors have speculated that Arab American women—particularly from the second generation and those with higher education—may question or openly revolt against the traditional gender roles that have been foisted upon them (e.g., Eid, 2003; Suleiman, 1999). This opposition to traditional gender roles may be stimulated by resentment against the double standards, what they perceive to be offensive beliefs about women and cultural restrictions, as well as pressures from mainstream society to shed aspects of the conservative traditions. Moreover, Arab immigrant women, especially among those who have higher socioeconomic status, may be less likely to adhere to traditional patriarchal gender roles compared to women in the Arab world (Marshall & Read, 2003).

Based on the emphasis of female gender roles within the family’s ethno-religious identity, it is reasonable to assume that Arab men would be more likely to assimilate to American culture compared to their female peers. Men have greater social freedom as youth and more opportunity to engage with the host culture through their work settings. Women also often arrive to America with less education, English language skills, driving skills, and comprehension of the American culture (Suleiman, 1999). Indeed, one study found that female Arab Americans showed higher levels of ethnic identity and intrinsic religiosity compared to males (Amer & Hovey, 2007). On the other hand, other research found no significant differences between male and female participants on measures of acculturation and ethnic identity (Gaudet et al., 2005) and acculturation stress (Amer, 2005; Wrobel, et al., 2009). One study of college students even found greater female assimilation to American culture and English language compared to males (Amin, 2000), which is in line with the theory that more educated second-generation women would be less likely to retain traditional gender roles (Read, 2004).

Elderly

As the family life cycle progresses, family roles reverse as young adults are expected to care for their elderly parents. The concept of having parents reside in nursing homes is an affront to traditional Arab values (Abudabbeh, 2005; Salari, 2002). Therefore, families play an important role for Arab American elders who often live near family members and ethnic social/community networks (Ajrouch, 2005). Despite family and community supports, Arab elderly face acculturative stressors such as pressures to gain competence in English language, to assimilate, and to maintain ethnic practices; all these pressures are associated with higher levels of depression (Wrobel et al., 2009).

Such acculturation tensions may be heightened for elderly Arab American parents who arrive to the USA to live with their adult children. They often remain isolated in their home environment; their freedoms and engagement with American society are restricted by lack of English language skills, transportation, and employment or other formal engagement (Christison, 1989). However, those who live in ethnic enclaves with other Arabic-speaking residents may not suffer as much from acculturative stress because the pressures to learn English and shed ethnic beliefs and practices would be reduced (Wrobel et al., 2009).

Arab American elders who were born and raised in the USA show greater acculturation and better mental health compared to their immigrant counterparts. For example, US-born Arab elderly are more likely to speak English and less likely to engage in Arab behavioral practices compared to immigrants (Ajrouch, 2008). They report larger and more diverse social networks (Ajrouch, 2005), with acculturation mediating this relationship between immigration status and social networks (Ajrouch, 2008). US-born elders also demonstrate better mental health including less loneliness (Ajrouch, 2008), less depression, and more life satisfaction, relationships that appear mediated by higher education and facility with English (Ajrouch, 2007).

Discrimination continues to be an acculturative stressor throughout the lifespan. It has been theorized that immigrant Arab elderly could potentially face more discrimination than the US-born Arab Americans because they would be more easily recognized as Arab based on their dress, accent, and cultural practices (Salari, 2002). On the other hand, one research study found that elderly who are born in the USA report significantly more perceived discrimination compared to immigrants, especially after September 11 (Ajrouch, 2005). This is consistent with the research presented above that indicated that persons who are more embedded in American society may be more likely to have opportunities to encounter discrimination.

Methodological Approaches

Most research with Arab American acculturation has been with adults, with fewer studies focusing on children or elderly. One of the primary challenges in Arab American research is recruiting participants, especially due to the geographically dispersed nature of the Arab American community. Moreover, because persons from the Middle East and North Africa are classified as “White,” they are an invisible minority and difficult to identify from sampling frames. To address this challenge, there have been two main methods of data collection. The first is through college campuses: advertising through student clubs, international student offices, and mass e-mailing (e.g., Barry, Elliott, & Evans, 2000). The second is community sampling, using key informants, religious institutions, and community centers as resources to recruit participants. Only a couple of studies have used traditional mailing methods (e.g., Alreshoud & Koeske, 1997; Faragallah et al., 1997). A more recently utilized strategy is Internet-based research (e.g., Amer & Hovey, 2007; Barry et al., 2000). This method is cheaper and less time-consuming, offers greater anonymity, and facilitates access to participants who reside in other cities. However, such studies are typically in English and thus exclude significant portions of the Arab American community who are less educated or affluent or are not as facile with the computer and Internet (e.g., the elderly).

Because there has been an emphasis on Berry’s acculturation model, many studies (e.g., Amer, 2005; Amer & Hovey, 2007; Amin, 2000; Barry, 2005) take the tack of classifying participants into acculturation orientations based on their self-reported endorsement of American and Arab cultures. This is usually measured with a question assessing desired (or actual) ethnic versus American cultural adoption. While this approach overlays nicely with theoretical perspectives because it categorizes participants into four groups, it is somewhat clumsy in statistical analyses that are reduced to group comparisons. Other researchers prefer to use more complex questionnaires to measure variability in cultural adoption. However, unfortunately there is a paucity of psychometrically sound and culturally sensitive instruments available. While many researchers choose to use widely available measures such as Phinney’s Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure, some questionnaires have been developed specifically for the Arab American population such as the Male Arab Ethnic Identity Measure (Barry et al., 2000).

Critique

Most of the research related to Arab American acculturation discussed above has been based on quantitative survey designs using questionnaires, or qualitative approaches. This has produced a substantial body of knowledge, particularly regarding Arab American immigration experiences and sociodemographic characteristics. However, risk and protective factors for the acculturation process have yet to be examined with more depth, and most studies use small sample sizes. As a result, the studies limit potential within-group comparisons (Faragallah et al., 1997), have produced contradictory findings that have not been resolved, and limit generalizability of the results.

Small-sample research tends to treat Arab Americans as a homogeneous group, which defies the reality of their heterogeneity. For example, Read (2004) discussed how Arab Americans are so diverse in terms of immigration status, demographics, religion, nation of origin, traditionalism, etc., that it is difficult to make generalizations or theories regarding the reasons for female labor force participation. Additionally, authors often do not frame or interpret their findings within the context of the ethnic density of the location where the sample was obtained. Living in an ethnic enclave can be a very different experience and may come with stronger social and community networks and less pressure to assimilate (Ajrouch, 2000).

There are concerns regarding the way Arab acculturation and assimilation to America has been presented in the literature. Many previous writers have depicted the Arab identity as a static experience that conflicts with American culture. The underlying assumption is that acculturation begins with point of arrival at the shores of the USA. However, it is important to remember that most Arab countries were colonized by European nations up to the mid-twentieth century, followed by decades of modernization and international exchange of ideas, products, and technologies (Eid, 2003). So in reality, those living in the Arab world have faced long-standing exposure to Western concepts and traditions, and many have assimilated these cultural imports while others have struggled against them and cultivated greater nationalism and Islamization to counteract them (Eid, 2003). Therefore, the relationship between Arab and Western cultures is complex and the process of acculturation begins prior to immigration.

The classification of Arab Americans into distinct acculturative strategies is also too simplistic to truly represent the diversity and complexity of their hyphenated identities. For example, Christison (1989) juxtaposed Palestinians who feel strong affiliation to their American identity but restrict their socialization to others from their ethnic group, to Palestinians who consider their residence in the USA to be transient and thus refuse the American citizenship but at the same time are immersed in American society with mostly American friends. Two studies (Amin, 2000; Britto & Amer, 2007) discovered a distinct subgroup of participants who endorsed “neutral” or midpoint levels of Arab and American identities; this group does not neatly fit in Berry’s four main strategies. In a study of Arab American women, Mango (2010) discussed how participants changed how they labeled their identity (e.g., American, Middle Eastern, Iraqi, Christian) based on the context of what they were discussing, indicating an identity that is complex and ever fluctuating. The author also suggested that the women faced a challenge finding wording that could embrace all their various identities.

Although Berry’s (1997) initial acculturation model took into account the influence of the host culture, research has generally overlooked the impact of the surrounding society on determining Arab Americans’ acculturation. An example of this contextual impact was seen in Beitin and Allen’s (2005) study of Arab American couples. Many of the couples experienced the construction of their identities as being determined or influenced by society’s own interpretation and negative messages about Arabs and Muslims. Ayish’s (2003) research on Arab youth found that over recent years, the youths’ specific self-labels have been replaced by internalization of more general labels (e.g., Arab, Muslim) that were imposed on them by post-9/11 societal stereotypes transmitted through media and peers.

Finally, the extant literature often views Arab Americans as a group that is suffering or in need; a narrative of resilience is generally unnoticed. In a departure from this problem-focused literature, a study of Arab American couples showed how they gained strength from overcoming traumas and stressors both in the homeland and in the USA and how they built upon multiple sources of family, community, and religious resources (Beitin & Allen, 2005). Similarly, a study of Arab American children found that they reported higher self-concept in multiple components (including physical appearance, academic skills, social relationships) compared to children living in Lebanon (Alkhateeb, 2010).

Implications for Community Practice and Research

Previous research has documented several risk factors and stressors for acculturating Arab Americans. Future research will need to bring greater visibility to voices of resilience and to identify protective factors that can be enhanced and emphasized in community-based programming. These programs can be developed by local ethnic-based community organizations such as the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services (ACCESS) and Arab American and Chaldean Council, both located in Detroit, Michigan. Protective factors can be fostered in interventions that target community members who are at risk for acculturative stressors (e.g., recent immigrants, Muslims, those with lower socioeconomic resources). For example, programs can aim to help orient immigrants to American culture, enhance English language skills, improve social networks, and negotiate between ethnic and host cultural demands. Because discrimination has emerged in the research as a salient acculturation stressor for Arab Americans, it is recommended that Arab communities collaborate with their local communities to develop interventions to address this issue. Efforts can focus on prejudice reduction within the local host community, enhanced coping skills among Arab recipients of discrimination, and policy aimed at protecting the Arab community.

Published literature can serve as a guidebook in developing priorities for program development. For example, it is evident that among youth, issues of bullying, school discrimination, and identity confusion may need to be addressed particularly in the school context and that nurturing ethnic identity can have salutary effects. However, further research is needed in several areas related to Arab acculturation such as more closely examining the contradictory findings on psychological outcomes of different acculturation orientations, identifying other acculturation stressors and protective factors, better understanding the experiences of younger children, and clarifying distinctions among more refined subgroups (e.g., based on nationality of origin, age at immigration). Moreover, it is preferable to not depend solely on scholarly literature but rather to develop interventions based on assessment of local community needs. In this way, programs can be tailored to meet the needs and strengths of specific subgroups (e.g., “female young adults seeking employment”). Such specifically tailored programming may diverge from currently available programs that serve more general groups such as “Arab immigrants.” All interventions should consider the acculturation status of participants such as language and literacy. Finally, program evaluation should be conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions and results should preferably be published in the scholarly literature so that other communities can access and build upon previous successes.

Notes

- 1.

Throughout this chapter the abbreviation “9/11” will be used to refer to the September 11, 2001, World Trade Center attacks.

References

Abudabbeh, N. (2005). Arab families: An overview. In M. McGoldrick, J. Giordano, & N. Garcia-Preto (Eds.), Ethnicity and family therapy (3rd ed., pp. 423–436). New York: The Guilford.

Abu-Ras, W., & Abu-Bader, S. H. (2009). Risk factors for depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): The case of Arab and Muslim Americans post-9/11. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 7, 393–418.

Ajrouch, K. (1999). Family and ethnic identity in an Arab-American community. In M. W. Suleiman (Ed.), Arab-Americans: Continuity and change (pp. 129–139). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Ajrouch, K. J. (2000). Place, age, and culture: Community living and ethnic identity among Lebanese American adolescents. Small Group Research, 31, 447–469.

Ajrouch, K. J. (2004). Gender, race, and symbolic boundaries: Contested spaces of identity among Arab American adolescents. Sociological Perspectives, 47(4), 371–391.

Ajrouch, K. J. (2005). Arab American elders: Network structure, perceptions of relationship quality, and discrimination. Research in Human Development, 2(4), 213–228.

Ajrouch, K. J. (2007). Resources and well-being among Arab-American elders. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology, 22, 167–182.

Ajrouch, K. J. (2008). Social isolation and loneliness among Arab American elders: Cultural, social, and personal factors. Research in Human Development, 5(1), 44–59.

Ajrouch, K. J., & Jamal, A. (2007). Assimilating to a White identity: The case of Arab Americans. International Migration Review, 41, 860–879.

Alkhateeb, H. M. (2010). Self-concept in Lebanese and Arab-American pre-adolescents. Psychological Reports, 106, 435–447.

Alreshoud, A., & Koeske, G. F. (1997). Arab students’ attitudes toward and amount of social contact with Americans: A causal process analysis of cross-sectional data. The Journal of Social Psychology, 137, 235–245.

Amer, M. M. (2005). Arab American mental health in the post September 11 era: Acculturation, stress, and coping. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The University of Toledo, Ohio.

Amer, M. M., & Hovey, J. D. (2007). Socio-demographic differences in acculturation and mental health for a sample of 2nd generation/early immigrant Arab Americans. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 9, 335–347.

Amer, M. M., Hovey, J. D., Fox, C. M., & Rezcallah, A. (2008). Initial development of the Brief Arab Religious Coping Scale (BARCS). Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 3, 69–88.

Amin, A. H. (2000). Cultural adaptation and psychosocial adjustment among Arab American college students. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL.

Awad, G. H. (2010). The impact of acculturation and religious identification on perceived discrimination for Arab/Middle Eastern Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 59–67.

Ayish, N. (2003). Stereotypes and Arab American Muslim high school students: A misunderstood group. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA.

Barry, D. T. (2005). Measuring acculturation among male Arab immigrants in the United States: An exploratory study. Journal of Immigrant Health, 7(3), 179–184.

Barry, D., Elliott, R., & Evans, E. M. (2000). Foreigners in a strange land: Self-construal and ethnic identity in male Arabic immigrants. Journal of Immigrant Health, 2(3), 133–144.

Beitin, B. K., & Allen, K. R. (2005). Resilience in Arab American couples after September 11, 2001: A systems perspective. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 31(3), 251–267.

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 46(1), 5–34.

Britto, P. R. (2008). Who am I? Ethnic identity formation of Arab Muslim children in contemporary U.S. society. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 853–857.

Britto, P. R., & Amer, M. M. (2007). An exploration of cultural identity patterns and the family context among Arab Muslim young adults in America. Applied Development Science, 11(3), 137–150.

Castro, V. S. (2003). Acculturation and psychological adaptation. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Christison, K. (1989). The American experience: Palestinians in the U.S. Journal of Palestine Studies, 18(4), 18–36.

Eid, P. (2003). The interplay between ethnicity, religion, and gender among second-generation Christian and Muslim Arabs in Montreal. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 35(2), 30–60.

El-Sayed, A. M., Tracy, M., Scarborough, P., & Galea, S. (2011). Suicide among Arab-Americans. PLoS ONE, 6(2), e14704. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014704.

Faragallah, M. H., Schumm, W. R., & Webb, F. J. (1997). Acculturation of Arab-American immigrants: An exploratory study. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 28(3), 182–203.

Gaudet, S., Clément, R., & Deuzeman, K. (2005). Daily hassles, ethnic identity and psychological adjustment among Lebanese-Canadians. International Journal of Psychology, 40(3), 157–168.

Hassouneh, D. M., & Kulwicki, A. (2007). Mental health, discrimination, and trauma in Arab Muslim women living in the US: A pilot study. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 10(3), 257–262.

Hassouneh, D., & Kulwicki, A. (2009). Family privacy as protection: A qualitative pilot study of mental illness in Arab-American Muslim women. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion, 20, 195–215.

Hattar-Pollara, M., & Meleis, A. I. (1995). Parenting their adolescents: The experiences of Jordanian immigrant women in California. Health Care for Women International, 16(3), 195–211.

Henry, H. M., Stiles, W. B., Biran, M. W., & Hinkle, S. (2008). Perceived parental acculturation behaviors and control as predictors of subjective well-being in Arab American college students. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 16, 28–34.

Keck, L. T. (1989). Egyptian Americans in the Washington, D.C. area. In B. Abu-Laban & M. W. Suleiman (Eds.), Arab-Americans: Continuity and change (pp. 103–126). Belmont: Association of Arab-American University Graduates.

Mango, O. (2010). Enacting solidarity and ambivalence: Positional identities of Arab American women. Discourse Studies, 12, 649–664.

Mansour, S. S. (2000). The correlation between ethnic identity and self-esteem among Arab American Muslim adolescents. Unpublished Master’s thesis, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV.

Marshall, S. E., & Read, J. (2003). Identity politics among Arab-American women. Social Science Quarterly, 84, 875–891.

Moradi, B., & Hasan, N. T. (2004). Arab American persons’ reported experiences of discrimination and mental health: The mediating role of personal control. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51, 418–428.

Naber, N. (2000). Ambiguous insiders: An investigation of Arab American invisibility. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 23(1), 37–61.

Naber, N. (2006). Arab American femininities: Beyond Arab virgin/American(ized) whore. Feminist Studies, 32(1), 87–111.

Naff, A. (1985). Becoming American: The early Arab immigrant experience. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Padela, A. I., & Heisler, M. (2010). The association of perceived abuse and discrimination after September 11, 2001, with psychological distress, level of happiness, and health status among Arab Americans. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 284–291.

Phinney, J. S., & Ong, A. D. (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3), 271–281.

Read, J. G. (2002). Challenging myths of Muslim women: The influence of Islam on Arab-American women’s labor force activity. The Muslim World, 92, 19–37.

Read, J. G. (2004). Culture, class, and work among Arab-American women. New York: LFB.

Richardson, A. (1967). A theory and a method for the psychological study of assimilation. International Migration Review, 2(1), 3–30.

Rudmin, F. W. (2003). Critical history of the acculturation psychology of assimilation, separation, integration, and marginalization. Review of General Psychology, 7(1), 3–37.

Rumbaut, R. G. (1997). Assimilation and its discontents: Between rhetoric and reality. International Migration Review, 31, 923–960.

Salari, S. (2002). Invisible in aging research: Arab Americans, Middle Eastern immigrants, and Muslims in the United States. The Gerontologist, 42, 580–588.

Samhan, H. H. (1987). Politics and exclusion: The Arab American experience. Journal of Palestine Studies, 16(2), 11–28.

Samhan, H. H. (1999). Not quite white: Race classification and the Arab-American experience. In M. W. Suleiman (Ed.), Arabs in America: Building a new future (pp. 209–226). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Seymour-Jorn, C. (2004). Arabic language learning among Arab immigrants in Milwaukee, Wisconsin: A study of attitudes and motivations. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 24(1), 109–122.

Shain, Y. (1996). Arab-Americans at a crossroads. Journal of Palestine Studies, 25(3), 46–59.

Suleiman, M. W. (1999). Introduction: The Arab immigrant experience. In M. W. Suleiman (Ed.), Arabs in America: Building a new future (pp. 1–21). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Wrobel, N. H., Farrag, M. F., & Hymes, R. W. (2009). Acculturative stress and depression in an elderly Arabic sample. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology, 24, 273–290.

Yoon, E., Langrehr, K., & Ong, L. Z. (2011). Content analysis of acculturation research in counseling and counseling psychology: A 22-year review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 83–96.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Amer, M.M. (2014). Arab American Acculturation and Ethnic Identity Across the Lifespan: Sociodemographic Correlates and Psychological Outcomes. In: Nassar-McMillan, S., Ajrouch, K., Hakim-Larson, J. (eds) Biopsychosocial Perspectives on Arab Americans. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-8238-3_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-8238-3_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-8237-6

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-8238-3

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)