Abstract

Concomitantly with the no-fault divorce revolution in the United States, there has been an increase in the divorce rate. From this observation, the question emerged of whether divorce law had a neutral effect on divorce behavior. Economists have conceptualized the issue by using an approach based on the “Coaseian” negotiation process, comparing unilateral divorce to divorce by mutual consent. The theoretical model predicts the neutrality of the law. But in the case of divorce, these assumptions are questionable. A determination as to the neutrality or non-neutrality of divorce law can thus be made based on empirical analysis. Early empirical studies came to conclusions favoring neutrality, but little by little, as methodological controversies accumulated, those empirical conclusions became more refined. Finally, a certain consensus emerged that the revolution in divorce would seem to have had a positive short-term impact on the divorce rate on the one hand, due more to the transition to unilateralism than to the abandonment of any reference to fault, and to have had a negative effect on the longer-term divorce rate on the other, because divorce law reform would seem to have prompted better-quality marriages.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The term “no-fault divorce revolution” comes from the United States. It originated in the debates that came about in the 1980s as one after another the various American states transitioned from at-fault divorce regimes to no-fault divorce regimes (about economic origins of no-fault divorce revolution; see Leeson and Pierson 2017). This change in American civil law stirred fierce conflict between the advocates of traditional family law and advocates of more progressive and feminist positions. The origins of this polemic are doubtless to be found in the stir created in the media and the political sphere by the alarmist book by Weitzman (1985). Based on data drawn from California State divorce rulings, the author showed that the introduction of no-fault divorce in that state would seem to have resulted in declines in the standard of living for the average female divorcee that were far more significant than had been the case prior to divorce law reform. Subsequent work (including Peterson 1996) showed Weitzman’s (1985) estimates to have been largely exaggerated; nevertheless the debate had been launched around the negative consequences of the no-fault divorce revolution. Parallel to questions about the estimation of consequences relative to the standard of living of ex-spouses following a divorce, the debate also focused heavily on whether or not this new divorce regime would in fact encourage divorce. In other words, was it the abandonment of fault as a condition of divorce that explained the increase in the divorce rate observed during that same period? Economists have seized upon this question, seeing it as an interesting application of the more general issue of the neutrality of law. Starting from the pioneering article by Peters (1986), the no-fault divorce revolution thus spread to scientific journals in economics and sociology as well, giving rise to a fairly extensive series of articles in which more recent articles challenged the preceding ones and so on.

Peters’ Pioneering Article Establishes the Theoretical Framework for Economic Analyses of the No-Fault Divorce Revolution

For Peters (1986), and subsequently for other economists, the discussion does not center on the concept of fault in itself but on the decision-making process: unilateral decision versus decision by mutual consent. In a no-fault divorce regime, either spouse may apply for divorce unilaterally on the grounds that he or she no longer wishes to live as a couple, even if their partner does not agree. In a fault-based divorce regime, an injured spouse cannot apply for a divorce if the offending spouse does not agree to it; mutual consent is required unless fault is proven in court. It was in particular the observation of frequent difficulties in proving fault (with negative effects) that led American legislators to abandon the at-fault divorce regime.

Peters (1986) then uses Coase’s theoretical model as an analytical framework to express the hypothesis of the neutrality of the law in regard to divorce: under certain conditions, negotiations can be arranged between the spouses, resulting only in efficient divorces, regardless of the divorce regime in force. The divorce regime in force would therefore be considered neutral.

Broadly, and making a simplified use of the notation proposed by Peters (1986), the gain derived from marriage R can be expressed as follows:

where p is the probability of divorce, M is the benefit derived from living as a couple, and Af and Am are the estimated postdivorce opportunities for the wife and husband, respectively, with the following assumptions:

M is fixed, known, and perfectly divisible.

Although Af and Am are not known with certainty, each spouse is fully aware of the opportunities available to their partner (informational symmetry), and these postdivorce gains are perfectly divisible.

A division of M was agreed upon at the time of marriage, attributing X to the wife and (M − X) to the husband.

The negotiations between the couple take place without transaction costs (because people in couple relationships know one another very well).

The divorce is thus a fairly simple matter: it will be an efficient divorce if M < (Af + Am); the husband will want a divorce if (M − Am) < X, and the wife will want a divorce if Af> X.

If both spouses want a divorce and the divorce is efficient, or, conversely, if both spouses wish to remain married and the divorce is not efficient, the question of the neutrality of the law does not arise. In the other two cases, the following reasoning will apply. The situation we will study will be one in which the husband wants a divorce but not the wife; the same reasoning may however be applied symmetrically, with the wife desiring the divorce and not the husband.

We will first look at a situation where the divorce would be efficient. If the divorce law in force is unilateral, the husband will ask for a divorce without taking his partner’s negative opinion into consideration; this behavior is efficient. If, on the other hand, mutual consent is required, the husband will have to negotiate his wife’s acceptance of the divorce: in an “at-fault” divorce regime, the spouse seeking the divorce thus negotiates the “right to remain married” held by the other party. The object of this negotiation is to grant compensation (Cf) to the wife in order at least to cancel out the loss that the divorce represents for her (X – Af):

The negotiation therefore concerns α, a coefficient that represents the extent to which the husband is willing to share the gains to be obtained from the divorce with his former spouse.

Secondly, in the case of divorce by mutual consent, the husband will not be able to obtain the divorce if the divorce is not already efficient prior to negotiation, because the gains he will derive from the divorce will be insufficient to compensate for the loss the divorce will represent for his partner, and it will thus be efficient to remain married. In the case of unilateral divorce, the husband will request a divorce a priori, with no need for negotiation. However, the wife is still able to negotiate in regard to her husband’s “right to divorce” and may in fact renegotiate the division of marriage gains X so that it is more in the husband’s interest to remain married than to separate:

Ultimately, whatever the divorce regime in place (unilateral or mutual consent), if negotiations are held under the assumed conditions (symmetry of information, no transaction cost, divisibility), the Coase model shows that only efficient divorce situations (M < (Af + Ah)) will arise. Thus the negotiated compensation system makes it possible, on the one hand, to avoid the inefficient divorces that might occur under a unilateral divorce regime and, on the other hand, to successfully conclude the efficient divorces that in a mutual consent divorce system could be blocked by one of the two spouses. The particular type of divorce law in force would thus be neutral with respect to divorce decisions, and so, empirically, there should be no increase in the divorce rate associated with the change in divorce regime.

Are the Hypotheses of the Coase Model Suited to an Analysis of the No-Fault Divorce Revolution?

Peters (1986) acknowledges that the hypotheses of the Coase negotiation model may be strong in the case of divorce. On the one hand, it is quite possible that symmetry of information regarding postdivorce opportunities for each of the spouses (Am+ Af) may not be respected (one strategy may consist in concealing this information, and such information may be costly to obtain). In this case, negotiation in the event of a unilateral divorce may result in the non-avoidance of inefficient divorces (insufficient negotiation of the share-out of marriage gains). And, in case of divorce by mutual consent, it is possible that efficient divorces may not be implemented (insufficient negotiation of compensation). If this is the case, an imperfect symmetry of information would lead to an increase in the divorce rate.

On the other hand, it is possible that marriage gains M may not initially be well known (at the time of marriage). In this case, in a unilateral divorce regime, since the wife cannot oppose the divorce and cannot expect to obtain compensation, it is possible that she will self-insure (by making less of an investment in the domestic sphere), which is likely to reduce marriage gains M and hence increase divorce probability p. In this scenario, the type of divorce is thus not neutral with regard to the divorce rate.

Zelder (1993a, b) analyzes two other limitations of the thesis of the neutrality of divorce law in a discussion of two other hypotheses. On the one hand, the author shows that in the presence of transaction costs, the divorce law is not neutral. The author first studies the situation of unilateral divorce regimes, where transaction costs are much lower (even zero) than those in mutual consent divorce regimes. This is the hypothesis most often retained in sociological studies based on the fact that unilateral divorce is simple and inexpensive. In the context of efficient divorce, in the first case (unilateral), the wife is not able to fully induce the husband to remain in the marriage for lack of sufficient means (which is in line with the assumption of legal neutrality). In the second case (mutual consent), the husband cannot induce the wife to divorce because the transaction costs would absorb her divorce surplus. There would thus be more divorces under unilateral divorce. The author then proceeds to study situations where transaction costs are prohibitive regardless of the divorce regime. In a unilateral divorce regime, if divorce is inefficient, the wife cannot induce the husband to remain in the marriage (whereas she could do so in the absence of transaction costs), and in a mutual consent divorce regime, the husband no longer has the means to induce his wife to divorce (in spite of his divorce surplus). There again, the divorce rate should be higher in unilateral divorce.

On the other hand, Zelder (1993a, b) also looks at the fact that marriage gains M may not be divisible and/or transferable (at least partially) between spouses, when said gains consist in a public good. Now, the primary marriage gain is often the child, who is, in fact, a public good. Under a unilateral divorce regime, when a child is present, even if the divorce is inefficient, the spouse who wishes to remain married will not be capable of inducing his or her partner to give up the divorce because their asset (the “consumption” of the child) is not transferable because it is not divisible. Again, under this assumption of indivisibility, the divorce rate should therefore be higher in unilateral divorce regimes.

These studies show that the neutrality of divorce law, as conceptualized through the Coase negotiation model, is highly dependent on the assumptions applied in the theoretical model. Thus empirical observation must ultimately be used to attempt to make a determination in regard to the neutrality of divorce law, in an investigation of whether or not the divorce rate observed does depend on the type of divorce regime in force.

Empirical Controversies Regarding the Impact of the No-Fault Divorce Revolution on the Divorce Rate

Because the various American states adopted the no-fault regime on different dates, the United States has provided an exceptional natural experimental site to study the relationship between the divorce rate and the type of divorce regime. Again in his pioneering article, Peters (1986) empirically demonstrates that divorce law is neutral, based on data from the Current Population Survey for 1979. His demonstration is based first of all on the observation that, all matters being otherwise equal, the fact of residence in a state that had opted for no-fault divorce was not significantly related to the probability of having had a divorce in the 4 years prior to the investigation. Secondly, his demonstration is supported by the observation that, on the other hand, residence in a State that had opted for no-fault divorce was positively and significantly correlated with the amount of compensation obtained (child support, alimony, etc.), which would thus support the negotiation hypothesis of the theoretical model.

Allen (1992), using the same data as Peters (1986), then challenged this demonstration by advancing three methodological criticisms. On the one hand, the status of states that made changes to divorce legislation during the 4-year observation period would appear to be ambiguous. On the other hand, the categorization of States according to the classification “at-fault versus no-fault” would appear highly debatable, insofar as there is a whole continuum of situations between strict at-fault regimes and strict no-fault regimes; for example, certain states had barred the attribution of fault for the submission of a divorce application but retained the notion of fault based on negotiations regarding the distribution of assets and compensation. This critique was also made by Brinig and Buckley (1998). Lastly, it would be a mistake to introduce State-based indicators into the specifications because of the correlation with the indicator “at-fault versus no-fault.” Taking these criticisms into account, Allen (1992) then shows that, contrary to the results obtained by Peters (1986), residence in a state that had opted for no-fault divorce is in fact positively and significantly related to the probability of divorce: the divorce regime would therefore not be considered neutral.

Peters (1992) responds to Allen (1992), accepting the first two criticisms and thus adopting the corrections proposed by Allen (1992) but rejecting the third criticism on the grounds that this specification allows consideration of an unobserved heterogeneity according to which it is possible that it was the States with the highest divorce rate that were the first to opt for a no-fault divorce regime (reversal of causality). In reassessing his model with two of the three corrections proposed by Allen (1992), Peters (1992) then reaches the same conclusion obtained in his original 1986 work, namely, that the type of divorce law is neutral with regard to the probability of divorce.

A year later, Zelder (1993a) published results based on different data (Panel Study of Income Dynamics). In the first estimate, the author confirms the conclusions reached by Peters (1992), by showing the absence of significant correlation between the probability of divorce and residence in a state that had opted for no-fault divorce. Then, in the second estimation, the author demonstrates the relevance of his public good hypothesis. To do so, the author crosses the indicator “at-fault versus no-fault” with an estimation of the public good (the share falling to the children – estimated based on expenditures for the children – in the total assets of the couple). The fact that this cross-variable has a regression coefficient that is significantly positive thus shows that residing in a State which has opted for no-fault divorce would encourage divorce when there are children present: divorce law would therefore not be neutral for married parents.

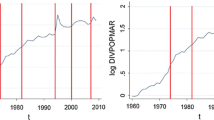

Another controversy then arose among researchers no longer using individual data but divorce rate time series by state. Nakonezny et al. (1995), using average 3-year divorce rates, show that divorce law is not neutral, insofar as these rates, observed before and after the transition to the no-fault divorce regime, are significantly different. Glenn (1997) criticizes this approach on the grounds that these estimations need to be corrected taking into account the general trend in divorce rates; the author shows that the differences highlighted by Nakonezny et al. (1995) are actually four times lower. Rodgers et al. (1997) then respond to Glenn (1997), accepting his criticism and introducing a corrective to reflect the trend but asserting that the new version is not adequate to reverse their initial conclusion of the non-neutrality of divorce law. Brinig and Buckley (1998) arrive at an identical conclusion, with different specifications. Without going directly into the controversy opposing Glenn with Rodgers et al., Ellman and Lohr (1998) propose a more elaborate methodology for correcting the trend, by taking into account peaks occurring before and after the legislative reform (the wait-and-see effect before, the surge effect after); yet their conclusions are mixed, suggesting that each State has a certain specificity. Glenn (1999) then once again revived the controversy with Rodgers et al. by questioning the method they used to calculate the trend (linear, over 10 years), insofar as the general progression of the divorce rate was not linear; it in fact accelerated at the end of the period, which with a linear specification would result in the attribution of part of that acceleration to the divorce law reform. Finally, Rodgers et al. (1999) responded to this criticism by means of a rather lengthy graphical analysis carried out on a state-by-state basis, an analysis which does not, however, lead to a definitive conclusion.

The third wave of controversy primarily involved Friedberg and Wolfers. Friedberg (1998) gathered all prior criticisms so as to better integrate them into his analysis of individual data: the issue of endogeneity, the issue of classifying states based on the types of divorce legislation in force, the issue of trend correction, etc. His conclusions are as follows: whereas on the one hand there would indeed seem to be an effect due to divorce law (the divorce rate was 6% lower in the States that did not make a change to their legislation), this impact would appear to have been due primarily to the transition to a completely no-fault divorce regime (when the notion of fault is partially preserved, the impact is weak), and the effect would seem to be fairly permanent (it was strong just after the reform and then strengthened over the next 2 years). Wolfers (2006) then criticizes Friedberg’s (1998) specification, primarily from the perspective considering the fixed “state-year” cross-effect (which mixes the fixed per-state effect and the effect of the reform) and the observation window being too short to take the trend into account. From the perspective of the results, his primary difference with Friedberg (1998) is that while the effect of the reform would indeed appear to be significant immediately after its entry into force, this effect nevertheless stabilizes after 8 years and then declines. This conclusion is consistent with that of Gruber (2004), using aggregate data drawn from several successive population censuses. Divorce law would thus appear to be non-neutral in the short term but neutral in the longer term. Drewianka (2008) then adds nuance to this conclusion. By separating no-fault divorce reforms from unilateral divorce reforms (since the two concepts are not strictly identical), the author shows that in fact the latter type of reform has an impact on the probability of divorce, and not the former.

The studies conducted by Wolfers (2006) are significant, because they open up a new research question: why does the impact of the no-fault divorce revolution diminish over time? The studies conducted by Rasul (2005) and Mechoulan (2006) then demonstrate the double impact of divorce law: in the short term, a transition to no-fault (easier) divorce leads to an increase in the divorce rate, and in the longer term this effect is offset by a negative impact on the divorce rate. Indeed, divorce becomes less probable because new marriages are of better quality (better, but later matches) in anticipation of the possibility of unilateral divorce easier to obtain and thus reducing marriage gains. In sum, the impact of the no-fault divorce revolution would appear fairly limited. In a certain way, 20 years later we came “full circle,” since Peters (1986), in his pioneering article, had suggested that the no-fault divorce revolution could ultimately lead to a drop in the divorce rate if, anticipating an easier divorce and thus a conduct of self-insurance on the part of wives (synonymous with decreased marriage gains), behavior on the marriage market (marriage and remarriage) tended toward greater selectivity in matching.

The debate over the no-fault divorce revolution has not really crossed the Atlantic. Few studies have examined the neutrality of divorce law in Europe. The few European works were late in coming and therefore have benefited from the methodological advances made in North American studies. Taking up the methodologies used by Friedberg (1998) and Wolfers (2006) and applying them to 14 European countries experiencing divorce reforms between 1950 and 2003 (excluding countries that legalized divorce during this period), Gonzales and Viitanen (2009) conclude that in Europe, a transition to no-fault divorce would seem to have had a positive and permanent effect on the divorce rate, whereas a transition to unilateral divorce would seem to have had a short-term positive effect, fading after 5 years (results quite similar to those obtained by Wolfers (2006) for the United States). Kneip and Bauer (2009) confirm the latter results by conducting a similar analysis of 18 European countries for the period 1960–2003. These authors, however, contribute an original clarification, by distinguishing de jure unilateral divorce from de facto unilateral divorce. Divorce is de facto unilateral when mutual consent is no longer required at the end of a (usually short) separation period undertaken by the couple. They then proceed to show that, without calling into question the very short-term positive effect (on the divorce rate) of de jure unilateral divorce reform, the move to de facto unilateral divorce would also seem to have had a positive effect on divorce rates but a permanent one. In sum, for the period 1970–1990, divorce law reforms in Europe would seem to account for one-third of the growth in the divorce rate (which grew by 2% in the same period), but would not at all explain the growth in the divorce rate before 1970 and after 1990. Bracke and Mulier (2017) discuss the classification of Gonzalez and Viitanen (2009) between no-fault divorce and unilateral divorce and propose to introduce in addition the reforms of procedure that make divorce easier. Reforms that reduce the duration of divorce proceedings (unilateral divorce being conditional on a period of de facto separation) would be also important. On the basis of data relating to Belgium and using a method of cointegration, they show that the reduction in the duration associated with the simplifications of 1994 had the same impact on the divorce trend as the introduction of unilateral divorce in 1974. They also estimate that a reduction of 1 month of legal divorce process would increase the divorce trend by 1.4%.

Conclusion

Economic analysis of the impact of the no-fault divorce revolution on divorce behavior has been a very interesting application, combining theory and empirical analysis, of the issue – very central to the economic analysis of law – of the neutrality of the law relative to individual behaviors. The refinement of econometric methodologies and the historical hindsight provided by the gradual accumulation of rich databases have led researchers to obtain nuanced conclusions, in particular by showing that the apparent neutrality of the divorce law relative to the divorce rate resulted, in fact, from the combination of a positive short-term effect and a negative longer effect (which is indirect, through marriage behavior). But as this revolution began to mature and the debate around the growth in the divorce rate was no longer really topical, other research questions emerged. How might divorce law impact negotiations with regard to specialization within couples, regarding premarital cohabitation, fertility, conjugal violence, female suicide, etc.?

Cross-References

References

Allen DW (1992) Marriage and divorce: comment. Am Econ Rev 82(3):679–685

Bracke S, Mulier K (2017) Making divorce easier: the role of no-fault and unilateral revisited. Eur J Law Econ 43(2):239–254

Brinig M, Buckley FH (1998) No-fault laws and at-fault people. Int Rev Law Econ 18(3):325–340

Drewianka S (2008) Divorce law and family formation. J Popul Econ 21:485–503

Ellman IM, Lohr SL (1998) Dissolving the relationship between divorce laws and divorce rates. Int Rev Law Econ 18(3):341–359

Friedberg L (1998) Did unilateral divorce raise divorce rates? Evidence from panel data. Am Econ Rev 88(4):608–627

Glenn ND (1997) A reconsideration of the effect of no-fault divorce on divorce rates. J Marriage Fam 59(4):1023–1025

Glenn ND (1999) Further discussion of the effects of no-fault divorce on divorce rates. J Marriage Fam 61(3):800–802

Gonzalez L, Viitanen TK (2009) The effect of divorce laws on divorce rates in Europe. Eur Econ Rev 53(2):127–138

Gruber J (2004) Is making divorce easier bad for children? The long-run implications of unilateral divorce. J Labor Econ 22(4):799–833

Kneip T, Bauer G (2009) Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates in Western Europe? J Marriage Fam 71:592–607

Leeson PT, Pierson J (2017) Economic origins of no-fault divorce revolution. Eur J Law Econ 43(3):419–439

Mechoulan S (2006) Divorce laws and the structure of the American family. J Leg Stud 35:143–174

Nakonezny PA, Schull RD, Rodgers JL (1995) The effect of no-fault divorce law on the divorce rate across the 50 states and its relation to income, education, and religiosity. J Marriage Fam 57(2):477–788

Peters EH (1986) Marriage and divorce: informational constraints and private contracting. Am Econ Rev 76(3):437–448

Peters EH (1992) Marriage and divorce, reply. Am Econ Rev 82(3):687–693

Peterson R (1996) A re-evaluation of the economic consequences of divorce. Am Sociol Rev 61(3):528–536

Rasul I (2005) Marriage markets and divorce laws. J Law Econ Org 22(1):30–69

Rodgers JL, Nakonezny PA, Schull RD (1997) The effect of no-fault divorce legislation: a response to a reconsideration. J Marriage Fam 59(4):1026–1030

Rodgers JL, Nakonezny PA, Schull RD (1999) Did no-fault divorce legislation matter? Definitely yes and sometimes no. J Marriage Fam 61(3):803–809

Weitzman LJ (1985) The divorce revolution: the unexpected social and economic consequences for women and children in America. The Free Press, New York

Wolfers J (2006) Did unilateral divorce raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. Am Econ Rev 96(5):1802–1820

Zelder M (1993a) The economic analysis of the effect of no-fault divorce law on the divorce rate. Harv J Law Public Policy 16(1):240–268

Zelder M (1993b) Inefficient dissolution as a consequence of public goods: the case of non-fault divorce. J Leg Stud 22:503–520

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature

About this entry

Cite this entry

Jeandidier, B. (2019). No-Fault Revolution and Divorce Rate. In: Marciano, A., Ramello, G.B. (eds) Encyclopedia of Law and Economics. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7753-2_678

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7753-2_678

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-7752-5

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-7753-2

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences