Abstract

Although methadone maintenance is a safe and effective treatment for opioid dependence that has been available for many years, its benefits have been limited by the requirement that it be used only in licensed specialized clinics. Treatment options have been substantially expanded by the introduction of buprenorphine for office-based maintenance. Buprenorphine has been shown to be as clinically effective as methadone [1–3] and cost-effective [4, 5], and even to be preferable in some patient populations [6]. In a study of heroin-dependent incarcerated men who were voluntarily randomly assigned to methadone or buprenorphine maintenance, all of the patients in the buprenorphine group stated that they would recommend the medication to others, 93 % of them intended to enroll in buprenorphine treatment after release, and one-quarter of the methadone patients intended to enroll in buprenorphine treatment instead [7].

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Although methadone maintenance is a safe and effective treatment for opioid dependence that has been available for many years, its benefits have been limited by the requirement that it be used only in licensed specialized clinics. Treatment options have been substantially expanded by the introduction of buprenorphine for office-based maintenance. Buprenorphine has been shown to be as clinically effective as methadone [1–3] and cost-effective [4, 5], and even to be preferable in some patient populations [6]. In a study of heroin-dependent incarcerated men who were voluntarily randomly assigned to methadone or buprenorphine maintenance, all of the patients in the buprenorphine group stated that they would recommend the medication to others, 93 % of them intended to enroll in buprenorphine treatment after release, and one-quarter of the methadone patients intended to enroll in buprenorphine treatment instead [7].

Buprenorphine and methadone treatment have each been shown to reduce drug-related risk behaviors in individuals with high risk of HIV transmission [8, 9]. Buprenorphine has also been shown to improve health-related quality of life [10]. In a 16-week study of buprenorphine maintenance with psychosocial counseling, responses on the Short Form 36 (a standard measure of health-related quality of life) showed improvements in bodily pain, vitality, mental health, social function, “role—emotional,” “role—physical,” and the mental-component summary score [11]. Studies of office-based treatment with buprenorphine are associated with retention rates and treatment outcomes comparable to those of methadone patients treated in opioid treatment programs (OTPs) [12–14].

In this chapter we review the procedures needed to start an office-based buprenorphine maintenance practice, including how to obtain the required license and training. We also describe buprenorphine formulations and storage regulations, and review how to assess patients and begin buprenorphine treatment. Finally, we provide information on monitoring patient outcome and discuss special patient populations.

Starting a Practice

Drug Addiction Treatment Act 2000

In 2000, the US Congress passed legislation intended to destigmatize opioid-addiction treatment and address the gap between the need for and availability of such treatment. This legislation—Title XXXV, Section 3502 of the Children’s Health Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-310)—enables qualified physicians to manage opioid addiction in their own practices and increases treatment options and availability [15]. Specifically, it permits qualified physicians to obtain a waiver to treat opioid addiction with Schedule III, IV, and V narcotic medications that have been specifically approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for that indication. This part of the law is known as the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000). Such medications may be prescribed and dispensed by waived physicians in treatment settings other than the traditional OTP (i.e., federally regulated methadone clinic) settings, including office-based settings. As of January 2012, the only medication that can be prescribed under this law is buprenorphine.

Qualifications for a Waiver

To qualify for a waiver under DATA 2000, a licensed physician (M.D. or D.O.) with a valid registration number from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) must be able to provide (or refer patients for) necessary ancillary services, such as mental health services, and must agree to limit the number of concurrently buprenorphine maintained patients in his or her practice to 30 in the first year and 100 after the first year. In addition, he or she must meet at least one of the training requirements (see Table 11.1).

Training

As shown in Table 11.1, to meet the guidelines defined in the law, a training program for office-based buprenorphine maintenance must be endorsed by one of five named professional organizations. Approved trainings are available in web-based, CD-ROM-based, and live formats, last about 8 h, and may earn AMA PRA Category 1 Credit (TM) for physicians who complete them. Depending on the program and the setting, there may be an associated cost to the physician. The trainings include evaluation to assess existing knowledge and attitudes, interactive modules focused on clinical skills and decision-making, post-training evaluations, and “practice change” advice on incorporation of buprenorphine treatment into the physician’s practice. Training can be found at the URLs (see Table 11.2).

Obtaining a Waiver

After successful completion of an approved Buprenorphine DATA 2000 Training Program, the physician must send a Notification of Intent to the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT), a branch of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), in order to obtain a waiver. The Notification of Intent must be submitted to CSAT before the initial dispensing or prescribing of opioid addiction therapy. The Notification of Intent should be submitted on a Waiver Notification Form (SMA-167) (available at http://www.buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/pls/bwns/waiver) and can be sent online, via fax, or by traditional ground mail to the SAMHSA Division of Pharmacologic Therapies (DPT). For more information on how to submit a Notification of Intent, go to http://www.buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/howto.html.

SAMHSA will send an acknowledgment letter (or email) indicating that notification is under active review. SAMHSA’s intent is to complete the review of notifications within 45 days of receipt. Upon completion of notification processing, SAMHSA will mail a letter confirming the waiver and containing a prescribing identification number (an “X number”) assigned by the DEA.

Prescribing and Storing

The regulations covering the ordering, storing, and dispensing of controlled substances vary by state. However, DEA regulations require that the prescribing physician’s “X number” be included on all buprenorphine prescriptions for opioid-addiction treatment, along with the physician’s regular DEA registration number.

When buprenorphine was first approved by the FDA, few pharmacies consistently kept the medication in stock. To deal with this problem, many physicians kept a supply of buprenorphine tablets on hand and dispensed them from their office. In-office buprenorphine dispensing is still legal under DATA 2000. However, physicians who wish to dispense buprenorphine from their offices must adhere to strict federal recordkeeping guidelines and must keep the resultant records for 2 years. The records should include inventories, including amounts of buprenorphine received and amounts dispensed; reports of theft or loss; destruction of controlled drugs; and records of dispensing. Additionally, the buprenorphine tablets must be stored in a secure, locked cabinet. Physicians who have their patients get their prescriptions filled at outside pharmacies and return to the office for induction are not subject to the same recordkeeping guidelines as physicians who store and dispense the tablets in-office [16].

Recordkeeping

DATA 2000 requires the DEA to inspect the practices of physicians who are providing office-based treatment of opioid dependence. DEA recordkeeping requirements go beyond the Schedule III recordkeeping requirements. Practitioners must keep records (including an inventory that accounts for amounts received and amounts dispensed) for all controlled substances dispensed, including buprenorphine products (21 PART 1304.03[b]). Practitioners must specifically record the prescription and dispensation of controlled substances for maintenance or detoxification treatment (21 CFR Section 1304.03[c]). AAAP provides guidance on preparing for a DEA inspection at http://www2.aaap.org/announcements/news-and-updates. Additional information can be found at http://www.pcssb.org/sites/default/files/How%20to%20Prepare%20for%20a%20DEA%20Inspection.pdf.

Barriers/Opportunities

Frequently cited barriers to the provision of office-based addiction treatment include inadequate clinician training, limited payment compared to what is available for other medical services, and concerns about confidentiality and stigma. In a qualitative study of 23 office-based physicians in New England, identified barriers included competing activities, lack of interest, lack of expertise in addiction treatment, patient concerns about confidentiality and cost, low patient motivation for treatment, lack of remuneration, limited ancillary support, not enough time, and a perceived low prevalence of opioid dependence in physicians’ practices. Respondents in the same study also cited several potential facilitators of office-based addiction treatment, including the promotion of continuity of patient care and viewing office-based treatment as a positive alternative to methadone maintenance [17].

Despite these barriers, buprenorphine treatment presents many opportunities for physicians, such as providing access to addiction treatment to populations not previously reached [12, 18] and integrating addiction treatment with primary care, HIV care, HCV care, and mental health care. It is estimated that methadone treatment options reach only 15–20 % of those in need of treatment [19]. In a 2005 evaluation of the waiver program, 31 % of patients taking buprenorphine were new to addiction treatment and 60 % were new to medication-assisted treatment [20]. These numbers reflect a clear gap between need and access, but also show that the waiver program and buprenorphine are helping to close the gap. Integration of addiction treatment and primary care has been shown to improve both medical and substance-abuse outcomes [21–24]. Additionally, integration of buprenorphine maintenance into clinical HIV care can have a positive impact on treatment retention and opioid use, as well as stabilizing or improving the biological markers of HIV [25]. Integrated buprenorphine care also presents the opportunity and infrastructure for increased treatment of hepatitis C [26, 27].

Probably the most frequently voiced suggestion for overcoming system-, provider-, and patient-level barriers to utilization of pharmacotherapy for addiction is to educate providers, patients, and the general public about the range of treatment options and about the outcomes that pharmacotherapies can produce [28, 29].

Buprenorphine

Pharmacology

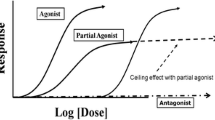

The pharmacology of buprenorphine is reviewed in detail in Chap. 10 of this text. Briefly, buprenorphine is a partial agonist at mu-opioid receptors, meaning that it binds strongly to receptors but does not activate them as strongly as endogenous opioids (or most abused opioids). At lower doses in opioid-naïve patients, its subjective and physiological effects increase with dose and are very similar to those of a full agonist. At higher doses, its effects reach a maximum beyond which increasing doses do not produce greater magnitudes of effect. This is termed the “ceiling effect.” At these higher doses buprenorphine can act like an antagonist, occupying mu receptors but only partially activating them while blocking other agonists from binding to and fully activating the receptor. Due to its high affinity for the receptor, buprenorphine can displace full opioid agonists from the receptor; once bound to the receptor, it is not readily displaced by full agonists or antagonists. Buprenorphine also has a slow dissociation rate from the receptor; clinically, this contributes to its long duration of effects.

At the kappa opioid receptor, buprenorphine is an antagonist. The clinical relevance of this component of buprenorphine’s actions is not fully understood.

Buprenorphine has poor gastrointestinal (GI) bioavailability and fair sublingual (under the tongue) bioavailability. The bioavailability of buprenorphine tablet administered sublingually is 29 % of that administered intravenously [15]. Buprenorphine is highly bound to plasma protein and is metabolized in the liver by the cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme to norbuprenorphine and other products. It undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism, which accounts for its poor GI bioavailability. For these reasons, buprenorphine is administered sublingually rather than orally.

Naloxone is included in some formulations of buprenorphine to minimize the risk of misuse by intravenous injection. Naloxone is an opioid antagonist with poor sublingual and GI bioavailability [30]. When the combination product is taken sublingually as prescribed, the effect of the naloxone is negligible. If the product is misused intravenously, the naloxone effect predominates, resulting in a decreased effect of buprenorphine in opioid-naïve individuals and precipitation of withdrawal in opioid-dependent individuals [31, 32].

Formulations

Buprenorphine is available for sublingual administration as a combination tablet (buprenorphine/naloxone) whose trade name is Suboxone. A monoproduct formulation (buprenorphine), trade name Subutex, was discontinued in September 2011, but a generic version of the buprenorphine monoproduct has been approved since May 2010. Buprenorphine combination products are also available as a sublingual film that was introduced in August 2010; the film is purported to dissolve in half the time of the tablet and have a more appealing taste. The sublingual tablet and film come in the same combination dosages: 8 mg buprenorphine with 2 mg naloxone or 2 mg buprenorphine with 0.5 mg naloxone. The buprenorphine monoproduct is available as an 8 or 2 mg sublingual tablet.

Slow-release formulations of buprenorphine are in various stages of development. These products are designed to minimize risks of patient noncompliance and diversion. A subcutaneous depot injection was shown to provide effective buprenorphine delivery for several weeks, with therapeutic effects persisting at fairly low buprenorphine plasma concentrations [33]. An implantable formulation of buprenorphine (Probuphine) that uses a polymer matrix sustained-release technology has been developed. In an initial, open-label evaluation, two doses of Probuphine were found to be safe, well-tolerated, and effective in patients with opioid dependence previously maintained on sublingual buprenorphine [34]. In a randomized trial conducted at 18 sites in the United States between April 2007 and June 2008, patients who received buprenorphine implants used fewer illicit opioids over 16 weeks (as assessed by urine testing) compared to those who received placebo implants [35].

Safety

For a complete listing of drug interactions, contraindications, warnings, and precautions, refer to the package inserts for Suboxone (http://www.suboxone.com/pdfs/SuboxonePI.pdf) and approved generics (e.g., http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=c3b4fb4e-db70-407f-8481-8ae934ef73f0).

Adverse Reactions and Contraindications

As with other mu-opioid agonists, the most common adverse reactions are nausea and constipation, but these effects appear to be less severe and more self-limited with buprenorphine than with full agonists. Other adverse reactions commonly reported with buprenorphine include oral hypoesthesia, glossodynia, oral mucosal erythema, headache, vomiting, hyperhidrosis, signs and symptoms of withdrawal, insomnia, pain, and peripheral edema.

The only contraindication to the use of buprenorphine is hypersensitivity to buprenorphine (or naloxone in the combination products). However, the prescribing information from Reckitt Benckiser lists a number of warnings and precautions that should be considered.

Drug–Drug Interactions

Buprenorphine is metabolized by the CYP3A4 isoenzyme of the P450 system. CYP3A4 inhibitors can result in higher levels of buprenorphine while CYP3A4 inducers can result in lower levels of buprenorphine. Buprenorphine patients who are starting or ending treatment with a CYP3A4 inhibitor or inducer should be closely monitored, and depending on the length of treatment with the CYP3A4 inhibitor/inducer and its effects, the dose of buprenorphine should be adjusted if needed.

Accidental Ingestion and Overdose

For full agonists at the mu-opioid receptor, the classic triad of signs of overdose is apnea (shallow respirations, <10 per minute), coma, and pinpoint pupils. Other signs include pulse rate <40 beats per minute, hypotension, cyanotic skin, flaccid muscles, and pulmonary edema [36]. Because buprenorphine is only a partial agonist, it has not been shown to cause these signs on its own. However, combination of buprenorphine with other CNS depressants, including benzodiazepines, can result in clinically significant toxicity.

Accidental ingestion of buprenorphine by swallowing results in milder effects than sublingual administration due to buprenorphine’s poor GI bioavailability.

The primary management of buprenorphine overdose is the establishment of adequate ventilation.

Abuse Potential and Diversion

Buprenorphine, like all mu agonists, has some abuse liability (potential to be diverted for deliberate misuse). The abuse liability of buprenorphine is lower than that of full agonists such as methadone, morphine, and heroin. If patients are abusing or diverting buprenorphine, arrangements should be made to transfer them to more closely supervised treatment.

Buprenorphine can produce physical dependence with repeated use, but due to its partial agonist activity, the degree of physical dependence may be less than that created by a full opioid agonist [37]. Withdrawal from buprenorphine shows a delayed onset and lesser severity compared to withdrawal from full mu-opioid agonists [38].

Buprenorphine can precipitate withdrawal in individuals who are physically dependent on full opioid agonists (heroin, morphine, methadone, etc.). Because of the presence of the antagonist naloxone, this effect will likely be severe if buprenorphine/naloxone combinations are misused and injected intravenously.

Diversion of buprenorphine does not appear to be driven by recreational use. SAMHSA/CSAT commissioned an independent assessment including a literature review, analysis of all available data, interviews with key state and federal officials, and consultation with a group of outside experts to determine the extent of buprenorphine diversion and abuse. The report, which came out in 2006, concluded: “[B]uprenorphine diversion and abuse are concentrated in specific geographic areas. The phenomenon may reflect lack of access to addiction treatment, as some nonmedical use appears to involve attempts to self-medicate with buprenorphine when formal treatment is not available. While the largest part of the diverted drug supply likely comes from buprenorphine prescribed by physicians—either for addiction or for pain—the presence of formulations that are not approved for use in the United States suggests that some is being illegally imported as well” [39]. In another study of 100 opioid users in Providence, RI, the majority of whom were interested in receiving treatment for opioid dependence, the authors found that among the 86 % of intravenous drug users who obtained buprenorphine illegally, 74 % did so to treat opioid withdrawal symptoms, 66 % to stop using other opioids, and 64 % because they could not afford drug treatment [40]. These findings suggest that improved access to buprenorphine treatment provided by licensed treatment providers might reduce buprenorphine diversion.

As part of the initial approval of buprenorphine for office-based treatment, the FDA required that the manufacturers create a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) to educate physicians, pharmacists, and patients. In response, the makers of Suboxone developed a list of recommendations for physicians (see Table 11.3).

Treating Patients with Buprenorphine

Patient Assessment/Patient Selection

Potential patients should be screened for the presence of an opioid-use disorder. Screening instruments include the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10, available at http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/screening-tools) [41], the CAGE Questions Adapted to Include Drugs (CAGE-AID) [42], and the National Institute on Drug Abuse-Modified Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (NMASSIST) [43] among others. Patients who screen positive on such a test should undergo a more complete assessment, including a mental-status exam and assessment of history regarding substance use, prior treatment, and medical, psychiatric, social, and family conditions. A complete physical exam is warranted in all patients with opioid-use disorders. The physical exam should include all the standard elements, with special attention given to the signs and symptoms of opioid use and its complications. Laboratory testing is also recommended.

Further details on all these elements of patient assessment are in Tables 11.4–11.6.

Patients who are appropriate for buprenorphine treatment have a diagnosis of addiction (typically operationalized in terms of the criteria for dependence from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision; DSM-IV-TR), are interested in treatment, and have no contraindications to buprenorphine. In addition, they should be reasonably likely to be compliant with buprenorphine treatment, understand the risks and benefits of treatment, and be willing to follow safety precautions. Other treatment options should be reviewed with the patients so that they can make an informed decision.

Conditions that may preclude buprenorphine treatment include dependence on benzodiazepines, alcohol, or other CNS depressants; untreated severe mental health issues; active or chronic suicidal or homicidal ideation or attempts; poor response to previous high-quality attempts at buprenorphine treatment; or significant medical conditions (Table 11.7).

Buprenorphine Induction

Once the patient has been assessed and found appropriate for buprenorphine treatment, plans can be made to begin the medication. Patients should be advised that on the first and perhaps second day of induction they may need to be in the clinic for several hours. Prior to initiation of buprenorphine treatment, the patient and physician should agree on a treatment contract delineating treatment goals, plan, consequences of poor adherence, and grounds for termination. Prior to the first dose of buprenorphine, the patient should not use heroin or other short-acting opioids for at least 12 h and should not use methadone or other long-acting opioids for at least 24 h. Buprenorphine induction can be undertaken with the buprenorphine–naloxone combination formulation unless the patient is pregnant or switching from long-acting opioids such as methadone (see section “Transferring from Methadone to Buprenorphine”).

Buprenorphine-induced precipitated withdrawal can occur with the first dose, but is often milder and shorter than that induced by an antagonist. The possibility of precipitated withdrawal is minimized if one decreases the dose of the full agonist (i.e., the opioid that patient is abusing), increases the time elapsed since last use of the full agonist prior to medicating with buprenorphine, and starts with a low dose of buprenorphine. The first dose of buprenorphine should be given when the patient has begun to develop early signs of opioid withdrawal (Table 11.8).

The severity of opioid withdrawal can be assessed with clinical tools such as the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale (COWS) [44]. A COWS score of >12 should be obtained prior to administration of the first dose of buprenorphine. Additional tools to assess opioid withdrawal include the Clinical Institute Narcotic Assessment (CINA) Scale for Opioid Withdrawal [45]; the Narcotic Withdrawal Scale [46]; and the Subjective Opiate Withdrawal Scale (SOWS) [47–49].

There now exist several clinical guidelines for the use of buprenorphine in an office-based setting. Physicians should be familiar with these guidelines, use their clinical judgment, and individualize treatment for the patient as indicated. Below we outline one approach based on these guidelines (Table 11.9).

Day 1—Once early withdrawal signs and symptoms are present, patients can be administered buprenorphine/naloxone 4/1 mg sublingually and observed for 2 or more hours. If withdrawal symptoms persist, a second buprenorphine/naloxone dose of 4/1 mg may be administered the same day, with the patient again observed for 2 or more hours. The maximum total dose on Day 1 is buprenorphine/naloxone 8/2 mg. If withdrawal symptoms abate, the Day 1 dose is established and the patient should be asked to return to the office the next day. If withdrawal symptoms persist despite administration of the maximum total Day 1 dose, the patient should counseled, given medications to manage withdrawal symptomatically, and asked to return the next day.

Day 2—When the patient returns to the office on Day 2, he or she should be assessed for withdrawal symptoms. If they are not present, then the patient’s daily dose is established at the total Day 1 dose. If on subsequent days the patient experiences mild withdrawal, the buprenorphine/naloxone dose should be adjusted based on clinical judgment and signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal in increments of 2/0.5 to 4/1 mg. If the patient does demonstrate symptoms of opioid withdrawal when he/she returns on Day 2, then he/she should be given the total Day 1 dose plus an additional 4/1 mg buprenorphine/naloxone and observed for 2 or more hours. If withdrawal symptoms are relieved, then the daily dose of buprenorphine/naloxone has been established. If withdrawal symptoms persist after 2 or more hours, the patient should be administered an additional buprenorphine/naloxone 4/1 mg and observed. If withdrawal symptoms are relieved, then the daily buprenorphine/naloxone dose has been established. The maximum Day 2 dose is buprenorphine/naloxone 16/4 mg. If the withdrawal symptoms have not dissipated, then the patient should be counseled, treated symptomatically, and asked to return the next day.

Day 3 onward—If the patient returns on Day 3 or on subsequent induction days with symptoms consistent with opioid withdrawal, he or she can continue with buprenorphine/naloxone 2/0.5 to 4/1 mg increases on a schedule similar to the Day 2 schedule above.

The goal of buprenorphine induction is to find the dose at which the patient has (1) discontinued or markedly decreased use of illicit opioids, (2) no cravings, (3) no opioid withdrawal, and (4) minimal or no adverse reactions. All dose adjustments during induction should be made based on clinical symptoms of opioid withdrawal and clinical judgment. In our clinical research setting, we have had success with waiting 12 h after administration of the last short-acting opioid and 24 h after the last long-acting opioid, waiting until mild opioid withdrawal is present, and then administering 8 mg buprenorphine on Day 1 without keeping the patient for observation or incremental dose increases. On Day 2, if opioid withdrawal is present, we administer buprenorphine 16 mg without keeping the patient for observation or incremental dose increases. We have had minimal precipitated withdrawal and loss to follow-up during induction. However, it should be kept in mind that in our setting, patients are seen for directly observed buprenorphine treatment daily throughout induction, stabilization, and maintenance. While there is variation among clinical guideline recommendations, the target dose is usually considered buprenorphine/naloxone 12/3 to 16/4 mg/day by the end of the first week, and the maximum recommended buprenorphine/naloxone dose is 32/8 mg/day.

Basic patient instructions for taking buprenorphine include telling the patient that the medication should be dissolved under the tongue and that drinking water to moisten the mouth before taking buprenorphine helps it dissolve. Patients should be advised not to chew or swallow tablet (or film) while it is dissolving because it will not work as well. Additionally, patients should be advised to avoid benzodiazepines, alcohol, and other CNS depressants, to keep their buprenorphine in a safe and secure place, to take buprenorphine once per day as directed, and not to change their dose without consulting a physician. Refer to the buprenorphine prescribing information (http://www.suboxone.com/pdfs/SuboxonePI.pdf) for a complete list of recommendations.

Complicated Inductions

Buprenorphine inductions may be complicated by precipitated or protracted withdrawal symptoms. In a retrospective chart review of the first 107 patients receiving buprenorphine treatment in an urban community health center, complicated inductions occurred in 18 (16.8 %) patients. When compared to routine inductions, complicated inductions predicted poorer treatment retention. Factors independently associated with complicated inductions included recent use of prescribed methadone, recent benzodiazepine use, and no prior experience with buprenorphine [50]. Although further research is needed, physicians should be aware of these potential risk factors and try to ensure that the patient is in mild withdrawal before the first dose of buprenorphine is administered, starting with a low dose of buprenorphine, and titrating up slowly.

Home Inductions

There is observational evidence that unobserved or “home” buprenorphine inductions are effective [51–56]. In two prospective studies of home induction, approximately 60–70 % of patients were successfully inducted, defined as being retained in treatment, on buprenorphine, and free of withdrawal, 1 week after the initial clinic visit. Complications were usually mild and infrequent, with only one case of confirmed severe precipitated withdrawal. Occasions requiring phone support from clinicians or staff were brief and infrequent [53, 56]. These findings are promising, but further research is still needed before home induction can be recommended for routine use.

Buprenorphine Stabilization and Maintenance

Stabilization begins when the patient has no cravings, no withdrawal, and minimal adverse drug reactions; this phase of treatment usually lasts 1–2 months. The duration of maintenance following stabilization should be individualized based on patient needs.

Once an effective buprenorphine dose has been established during induction, the patient should be continued on this daily dose and adjustments made as needed. Dose adjustments should be based on a combination of patient preference and clinical judgment, balancing the positive effects of buprenorphine (relief of opioid withdrawal, greatly diminished opioid craving, and cessation of illicit opioid use) with its possible side effects (such as constipation and sedation). Dose adjustments can be made in buprenorphine/naloxone 2/0.5 to 4/1 mg increments per week with a maximum daily dose of buprenorphine/naloxone of 32/8 mg. If the maximum dose is reached and maintained but illicit opioid use persists, efforts should be made to intensify the level of nonpharmacological treatment, or consideration should be given to transferring the patient to an OTP that can provide more intense care.

Regardless of buprenorphine dose, all patients should be offered access or referral to evidence-based psychosocial treatment and other nonpharmacological treatments as stipulated by DATA 2000. Follow-up frequency should be individualized, but typically, once weekly in the first month is appropriate. Buprenorphine prescriptions should reflect the length of time between visits; providing multiple refills early in treatment is discouraged. With negative urine drug toxicologies on a stable buprenorphine dose, visits and prescriptions can be monthly. Visit frequency and interval should be adjusted as needed to reflect the patient’s treatment-plan compliance, demonstrated responsibility, side effects, and abstinence from illicit drugs.

Periodic, usually monthly, drug toxicology screening is an important adjunct to buprenorphine treatment. A number of screening options exist, including by urine, blood, saliva, sweat, and hair. A combination of both random and nonrandom (e.g., at monthly office visit) urine toxicology testing should be implemented. Of note, buprenorphine does not come up as positive on the standard opioid toxicology screens which test for morphine/codeine and their derivatives. If testing for buprenorphine compliance, point-of-care urine screens (i.e., dipsticks) specifically for buprenorphine are commercially available. Additionally, periodic random pill counts might be a useful adjunct for monitoring patient safety and minimizing the risk of diversion.

Medically Supervised Buprenorphine Withdrawal

Research and clinical experience have shown that opioid maintenance treatments have a higher likelihood of success than withdrawal treatment. If medically supervised withdrawal (MSW) is initiated, the evidence shows that longer withdrawal plans (>30 days) tend to have more long-term success than shorter withdrawal plans (<30 days) [57, 58]. MSW is usually undertaken in two phases: induction, during which the patient is stabilized (minimal opioid withdrawal and cessation of illicit opioid use) as quickly as possible, and dose reduction, during which the buprenorphine dose is decreased and then discontinued.

Patient Management Issues

Adherence and Retention

Treatment adherence is enhanced by a therapeutic relationship between patient and physician built on trust, mutual respect, and a two-way exchange of information. Prolonged inductions resulting in continued opioid withdrawal signs and symptoms have been shown to increase the treatment drop-out rate [59] so every effort should be made to reach an adequate buprenorphine maintenance dose as quickly as possible, within the constraints imposed by the avoidance of precipitated withdrawal.

Ending Maintenance Treatment

Longer maintenance treatment is associated with less illicit drug use and relapse, longer retention in treatment [60], and fewer complications [61]. During maintenance, the patient’s desire to taper off buprenorphine should periodically be revisited. If the patient expresses an interest in ending buprenorphine maintenance, the patient and physician should discuss the likelihood of successful taper and consider housing and income stability, adequacy of social support, and absence of legal problems. When the decision is made to discontinue buprenorphine treatment, the dose should be tapered slowly, ideally over weeks to months, at a rate agreed upon by patient and physician. If craving or withdrawal symptoms emerge, the taper should temporarily be suspended, then resumed once the symptoms have abated. The presence of both formal and informal psychosocial support can be critical during all of treatment, but especially during dose tapers.

Coordination of Care/Role of the MD

Prior to offering office-based buprenorphine treatment, physicians should familiarize themselves with federal and state regulations, training requirements, treatment guidelines, buprenorphine prescribing information, and the most recent scientific literature pertaining to buprenorphine. Additionally, clinical and administrative staff in the physician’s office should be educated about addiction and about buprenorphine treatment. The physician and his or her staff should develop “standard operating procedures” for the care of buprenorphine patients. This should include compiling a list of available psychosocial services (individual and group counseling, support groups, etc.) and other community services (case management, food banks, homeless shelters, job training, needle-exchange, etc.), and all staff should become familiar with service locations, hours, and participation requirements.

The privacy and confidentiality of patients in addiction treatment are protected by federal law. Physicians and their staff should be familiar with these regulations and establish office procedures to ensure that they are maintained. A procedure through which patients can authorize release of records should be developed and implemented so that physicians may communicate with pharmacists, psychosocial treatment providers, subspecialty physicians, and other providers as needed.

Working with Pharmacies

Given the privacy regulations in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and 42 CFR Part 2, it is advisable to have a patient sign an authorization for release of information between the physician and the pharmacist prior to their first buprenorphine dose. This will allow the physician to verify the buprenorphine prescription if needed, and it is important if the prescription is being phoned or faxed. Also, with authorization to communicate with the pharmacy, the physician can more easily address pre-authorization requirements from insurance companies to ensure that there is no delay in getting the prescription filled. More information regarding these regulations can be found at http://www.samhsa.gov/healthprivacy/.

FDA information for pharmacists on buprenorphine is available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/UCM191533.pdf.

Special Populations

Transferring from Methadone to Buprenorphine

Patients on methadone maintenance can be successfully transferred to buprenorphine maintenance [62]. This may be an option to consider for patients who have tolerable but undesirable side effects with methadone, or who want the increased flexibility that office-based buprenorphine allows once stabilization and maintenance occur. Additional reasons for transfer might include a perceived decrease in stigma, longer duration of action, and enhanced safety. When patients prepare to transfer, it is advised that their methadone dose be tapered down to 30 mg/day and maintained at that level for ideally 5–7 days prior to initiating buprenorphine treatment in order to reduce the likelihood of buprenorphine-precipitated withdrawal. Patients are also asked to wait at least 24 h after their last dose of methadone, by which time they should begin to experience symptoms of early withdrawal, prior to initiating buprenorphine. The likelihood of precipitated withdrawal may be further reduced by starting at an initially low dose (such as 2–4 mg) of buprenorphine, using the buprenorphine monotherapy formulation (no naloxone), and waiting until the patient is in mild to moderate withdrawal (e.g., COWS score >12). As with buprenorphine induction in patients who use short-acting opioids, the suggested maximum Day 1 dose for patients using long-acting opioids such as methadone is buprenorphine 8 mg. On Day 2, the patient may proceed according to the Day 2 schedule for short-acting opioids and be administered the combination of buprenorphine/naloxone.

Pregnant Women

In the United States, methadone has been the standard of care for treating opioid addiction in pregnant woman and their neonates. Pregnant women seeking buprenorphine treatment should be advised that the FDA currently classifies buprenorphine as a Category C agent. However, recent results from the MOTHER Study suggest that buprenorphine is safe and effective in pregnant women, with lower neonatal withdrawal rates and shorter neonatal withdrawal durations compared to methadone [63]. A multicenter European prospective study comparing buprenorphine to methadone also found buprenorphine as safe as methadone in the treatment for pregnant opioid-dependent women [64].

Breastfeeding while on buprenorphine is controversial, with the package insert advising against it but the Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) 40 consensus panel stating it is not contraindicated. In lactating women given buprenorphine at therapeutic levels, the concentration present in the breast milk was considered low [65].

Criminal Justice

Buprenorphine has proven to be a very effective tool in addressing opioid-use disorders in criminal-justice settings such as prisons [66, 67]. However, after incarceration, relapse rates are high and overdose on illicit opioids is common [68–70]. Physicians should be vigilant of their patients during this transition time and attempt to re-engage them in treatment as quickly as possible.

Adolescents/Young Adults and the Elderly

Buprenorphine has been shown to be a safe and effective treatment in adolescents and young adults. In a study by Marsch et al., comparing buprenorphine to clonidine in a 28-day detoxification, buprenorphine-treated participants were significantly more likely to be retained in treatment (72 % vs. 39 %) and had a higher percentage of opiate-negative urines (64 % vs. 32 %). Participants in both groups reported relief of withdrawal symptoms and reductions in HIV risk behaviors [71]. A 2012 study examining the outcome of buprenorphine and methadone treatment for heroin dependence among adolescents (average age 16.6 years) found that half of the participants remained in treatment for over 1 year, and among those still in treatment at 12 months, 39 % were heroin-abstinent [72].

State law varies on the circumstances under which parental consent is needed, so physicians wishing to treat adolescents and young adults should be aware of the regulations in their state.

Caution should be used when administering buprenorphine in elderly or debilitated patients or patients with liver dysfunction, as drug metabolism and absorption may be altered.

Reimbursement

Reimbursement for addiction treatment and mental health care has been limited, but advances are being made. In 2008, the Paul Wellstone Mental Health and Addiction Equity Act of 2007 (HR 1424) was signed into law. The law expands access to mental health and addiction treatment and prohibits third-party payers from placing discriminatory restrictions on reimbursement. In 2007, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) adopted new codes in the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) for assessment and intervention services for substance abuse (H0049 and H0050) and in January 2008, the American Medical Association adopted Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for screening and brief intervention (99408 and 99409), and new Medicare “G” codes (G0396 and G0397) became available that parallel the CPT codes. However, there are currently no specific billing codes in addiction medicine that physicians can use for office-based treatment of opioid dependence, and reimbursement by third-party payers continues to vary. The billing codes for inpatient detoxification, outpatient detoxification, and office-based maintenance are the same as codes for other ambulatory care services.

Resources

American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry—Email: information@aaap.org. Website: www.aaap.org.

American Osteopathic Association—Email: info@osteotech.org. Website: www.osteopathic.org.

American Psychiatric Association—Email: apa@psych.org. Website: www.psych.org.

American Society of Addiction Medicine—Email: email@asam.org. Website: www.asam.org.

CSAT Buprenorphine Information Center—1.866.BUP.CSAT (1.866.287.2728). Email: info@buprenorphine.samhsa.gov. Website: http://www.buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/index.html.

Federation of State Medical Boards—Website: www.fsmb.org/pdf/2002_grpol_opioid_addiction_treatment.pdf.

National Alliance of Advocates for Buprenorphine Treatment—Website: www.naabt.org.

SAMHSA Sponsored Buprenorphine Physician Clinical Support System (PCSS)—The SAMHSA-funded PCSS is a national network of trained physician mentors with expertise in buprenorphine treatment and skilled in clinical education designed to assist practicing physicians in incorporating into their practices the treatment of prescription opioid- and heroin-dependent patients using buprenorphine. Website: http://www.pcssb.org/.

References

Johnson RE, Jaffe JH, Fudala PJ. A controlled trial of buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence. JAMA. 1992;267(20):2750–5. doi:10.1001/jama.267.20.2750.

Mattick RP, Ali R, White JM, O’Brien S, Wolk S, Danz C. Buprenorphine versus methadone maintenance therapy: a randomized double-blind trial with 405 opioid-dependent patients. Addiction. 2003;98(4):441–52. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00335.x.

Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD002207. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub3.

Barnett PG, Zaric GS, Brandeau ML. The cost-effectiveness of buprenorphine maintenance therapy for opiate addiction in the United States. Addiction. 2001;96(9):1267–78. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96912676.x.

Barnett PG. Comparison of costs and utilization among buprenorphine and methadone patients. Addiction. 2009;104(6):982–92. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02539.x.

Maremmani I, Gerra G. Buprenorphine-based regimens and methadone for the medical management of opioid dependence: selecting the appropriate drug for treatment. Am J Addict. 2010;19(6):557–68. doi:10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00086.x.

Awgu E, Magura S, Rosenblum A. Heroin-dependent inmates’ experiences with buprenorphine or methadone maintenance. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42(3):339–46.

Gowing L, Farrell MF, Bornemann R, Sullivan LE, Ali R. Oral substitution treatment of injecting opioid users for prevention of HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD004145. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004145.pub4.

Sullivan LE, Moore BA, Chawarski MC, Schottenfeld RS, O’Connor PG, Fiellin DA. Buprenorphine reduces HIV risk behavior among opioid dependent patients in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:172.

Giacomuzzi SM, Ertl M, Kemmler G, Riemer Y, Vigl A. Sublingual buprenorphine and methadone maintenance treatment: a three-year follow-up of quality of life assessment. ScientificWorldJournal. 2005;5:452–68. doi:10.1100/tsw.2005.52.

Raisch D, Campbell H, Garnand D, Jones M, Sather M, Naik R, et al. Health-related quality of life changes associated with buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(7):1177–83.

Sullivan LE, Chawarski M, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. The practice of office-based buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: is it associated with new patients entering into treatment? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(1):113–6. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.008.

Marsch LA, Stephens MAC, Mudric T, Strain EC, Bigelow GE, Johnson RE. Predictors of outcome in LAAM, buprenorphine, and methadone treatment for opioid dependence. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;13(4):293–302. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.13.4.293.

Stein MD, Cioe P, Friedmann PD. Brief report: buprenorphine retention in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1038–41. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0228.x.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Clinical guidelines for the use of buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid addiction, Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) series 40. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2004.

Clinical Tools I. BupPractice 1995–2011. http://www.buppractice.com/. Updated Wednesday, 4 Jan 2012, 10:43 am; cited 4 Jan 2012.

Barry DT, Irwin KS, Jones ES, Becker WC, Tetrault JM, Sullivan LE, et al. Integrating buprenorphine treatment into office-based practice: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):218–25. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0881-9.

Fiellin DA, Rosenheck RA, Kosten TR. Office-based treatment for opioid dependence: reaching new patient populations. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1200–4. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1200.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction in opioid treatment programs, Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) series 43. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Evaluation of the Buprenorphine Waiver Program: results from SAMHSA/CSAT’s evaluation of the Buprenorphine Waiver Program 2005. http://www.buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/findings.pdf. Cited 31 Jan 2012.

Mertens JR, Flisher AJ, Satre DD, Weisner CM. The role of medical conditions and primary care services in 5-year substance use outcomes among chemical dependency treatment patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;98(1–2):45–53. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.04.007.

O’Toole TP, Pollini RA, Ford DE, Bigelow G. The effect of integrated medical-substance abuse treatment during an acute illness on subsequent health services utilization. Med Care. 2007;45(11):1110–5.

Samet JH, Friedmann P, Saitz R. Benefits of linking primary medical care and substance abuse services—patient, provider, and societal perspectives. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(1):85–91. doi:10.1001/archinte.161.1.85.

Saitz R, Horton NJ, Larson MJ, Winter M, Samet JH. Primary medical care and reductions in addiction severity: a prospective cohort study. Addiction. 2005;100(1):70–8. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00916.x.

Sullivan LE, Barry D, Moore BA, Chawarski MC, Tetrault JM, Pantalon MV, et al. A trial of integrated buprenorphine/naloxone and HIV clinical care. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:S184–90. doi:10.1086/508182.

Kresina TF, Eldred L, Bruce RD, Francis H. Integration of pharmacotherapy for opioid addiction into HIV primary care for HIV/hepatitis C virus-co-infected patients. AIDS. 2005;19:S221–6. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000192093.46506.e5.

Edlin BR, Kresina TF, Raymond DB, Carden MR, Gourevitch MN, Rich JD, et al. Overcoming barriers to prevention, care, and treatment of hepatitis C in illicit drug users. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:S276–85. doi:10.1086/427441.

Gordon AJ, Kavanagh G, Krumm M, Ramgopal R, Paidisetty S, Aghevli M, et al. Facilitators and barriers in implementing buprenorphine in the Veterans Health Administration. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25(2):215–24. doi:10.1037/a0022776.

Oliva EM, Maisel NC, Gordon AJ, Harris AHS. Barriers to use of pharmacotherapy for addiction disorders and how to overcome them. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(5):374–81. doi:10.1007/s11920-011-0222-2.

Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA. Effects of sublingually given naloxone in opioid-dependent human volunteers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1990;25(1):27–34. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(90)90136-3.

Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA. Buprenorphine and naloxone alone and in combination in opioid-dependent humans. Psychopharmacology. 1988;94(4):484–90. doi:10.1007/bf00212842.

Weinhold LL, Preston KL, Farre M, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE. Buprenorphine alone and in combination with naloxone in nondependent humans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1992;30(3):263–74. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(92)90061-g.

Sigmon SC, Moody DE, Nuwayser ES, Bigelow GE. An injection depot formulation of buprenorphine: extended biodelivery and effects. Addiction. 2006;101(3):420–32. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01348.x.

White J, Bell J, Saunders JB, Williamson P, Makowska M, Farquharson A, et al. Open-label dose-finding trial of buprenorphine implants (Probuphine)(R) for treatment of heroin dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;103(1–2):37–43. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.008.

Ling W, Casadonte P, Bigelow G, Kampman KM, Patkar A, Bailey GL, et al. Buprenorphine implants for treatment of opioid dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(14):1576–83.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Eissenberg T, Greenwald MK, Johnson RE, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Buprenorphine’s physical dependence potential: antagonist-precipitated withdrawal in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276(2):449–59.

Eissenberg T, Johnson RE, Bigelow GE, Walsh SL, Liebson IA, Strain EC, et al. Controlled opioid withdrawal evaluation during 72 h dose omission in buprenorphine-maintained patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;45(1–2):81–91. doi:10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01347-1.

Center for Health Services and Outcomes Research. Diversion and abuse of buprenorphine: a brief assessment of emerging indicators; http://buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/Vermont.Case.Study_12.5.06.pdf, 2006.

Bazazi AR, Yokell M, Fu JJ, Rich JD, Zaller ND. Illicit use of buprenorphine/naloxone among injecting and noninjecting opioid users. J Addict Med. 2011;5(3):175–80. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182034e31.

Skinner HA. The drug-abuse screening-test. Addict Behav. 1982;7(4):363–71. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3.

Brown R, Rounds L. Conjoint screening questionnaires for alcohol and other drug abuse: criterion validity in a primary care practice. Wis Med J. 1995;94(3):135–40.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. NMAssist: screening for tobacco, alcohol and other drug use. http://www.drugabuse.gov/nidamed/nmassist-screening-tobacco-alcohol-other-drug-use. Cited 31 Jan 2012.

Wesson DR, Ling W. The clinical opiate withdrawal scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(2):253–9.

Peachey JE, Lei H. Assessment of opioid dependence with naloxone. Br J Addict. 1988;83(2):193–201.

Fultz JM, Senay EC. Guidelines for management of hospitalized narcotic addicts. Ann Intern Med. 1975;82(6):815–8.

Bradley BP, Gossop M, Phillips GT, Legarda JJ. The development of an opiate withdrawal scale (OWS). Br J Addict. 1987;82(10):1139–42.

Gossop M. The development of a short opiate withdrawal scale (SOWS). Addict Behav. 1990;15(5):487–90. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(90)90036-w.

Handelsman L, Cochrane KJ, Aronson MJ, Ness R, Rubinstein KJ, Kanof PD. Two new rating-scales for opiate withdrawal. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1987;13(3):293–308. doi:10.3109/00952998709001515.

Whitley SD, Sohler NL, Kunins HV, Giovanniello A, Li XA, Sacajiu G, et al. Factors associated with complicated buprenorphine inductions. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;39(1):51–7. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2010.04.001.

Mintzer IL, Eisenberg M, Terra M, MacVane C, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Treating opioid addiction with buprenorphine-naloxone in community-based primary care settings. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(2):146–50. doi:10.1370/afm.665.

Lee JD, Grossman E, Dirocco D, Gourevitch MN. Feasibility of at-home induction in primary care-based buprenorphine treatment: is less more? J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:303–4.

Lee J, DiRocco D, Grossman E, Gourevitch MN. At-home buprenorphine induction in urban primary care. Subst Abus. 2009;30(2):191.

Soeffing JM, Martin LD, Fingerhood MI, Jasinski DR, Rastegar DA. Buprenorphine maintenance treatment in a primary care setting: outcomes at 1 year. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37(4):426–30. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2009.05.003.

Sohler NL, Li X, Kunins HV, Sacajiu G, Giovanniello A, Whitley S, et al. Home- versus office-based buprenorphine inductions for opioid-dependent patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38(2):153–9. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2009.08.001.

Gunderson EW, Wang XQ, Fiellin DA, Bryan B, Levin FR. Unobserved versus observed office buprenorphine/naloxone induction: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Addict Behav. 2010;35(5):537–40. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.01.001.

Dunn KE, Sigmon SC, Strain EC, Heil SH, Higgins ST. The association between outpatient buprenorphine detoxification duration and clinical treatment outcomes: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;119(1–2):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.033.

Katz EC, Schwartz RP, King S, Highfield DA, O’Grady KE, Billings T, et al. Brief vs. extended buprenorphine detoxification in a community treatment program: engagement and short-term outcomes. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35(2):63–7. doi:10.1080/00952990802585380.

Soyka M, Zingg C, Koller G, Kuefner H. Retention rate and substance use in methadone and buprenorphine maintenance therapy and predictors of outcome: results from a randomized study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11(5):641–53. doi:10.1017/s146114570700836x.

Kakko J, Svanborg KD, Kreek MJ, Heilig M. 1-Year retention and social function after buprenorphine-assisted relapse prevention treatment for heroin dependence in Sweden: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9358):662–8. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12600-1.

Stein MD, Friedmann PD. Optimizing opioid detoxification: rearranging deck chairs on the titanic. J Addict Dis. 2007;26(2):1–2. doi:10.1300/J069v26n02_01.

Salsitz EA, Holden CC, Tross S, Nugent A. Transitioning stable methadone maintenance patients to buprenorphine maintenance. J Addict Med. 2010;4(2):88–92. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181add3f5.

Jones HE, Kaltenbach K, Heil SH, Stine SM, Coyle MG, Arria AM, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome after methadone or buprenorphine exposure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(24):2320–31. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1005359.

Lacroix I, Berrebi A, Garipuy D, Schmitt L, Hammou Y, Chaumerliac C, et al. Buprenorphine versus methadone in pregnant opioid-dependent women: a prospective multicenter study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67(10):1053–9. doi:10.1007/s00228-011-1049-9.

Grimm D, Pauly E, Poschl J, Linderkamp O, Skopp G. Buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine concentrations in human breast milk samples determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Ther Drug Monit. 2005;27(4):526–30. doi:10.1097/01.ftd.0000164612.83932.be.

Fiellin D, Moore B, Wang E, Sullivan L. Primary care office-based buprenorphine/naloxone treatment and the legal and criminal justice system. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:366.

Cropsey KL, Lane PS, Hale GJ, Jackson DO, Clark CB, Ingersoll KS, et al. Results of a pilot randomized controlled trial of buprenorphine for opioid dependent women in the criminal justice system. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;119(3):172–8. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.021.

Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Lindsay RG, Stern MF. Risk factors for all-cause, overdose and early deaths after release from prison in Washington state. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117(1):1–6. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.029.

Ochoa KC, Davidson PJ, Evans JL, Hahn JA, Page-Shafer K, Moss AR. Heroin overdose among young injection drug users in San Francisco. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80(3):297–302. doi:10.1016/j.druglacdep.2005.04.012.

Krinsky CS, Lathrop SL, Brown P, Nolte KB. Drugs, detention, and death a study of the mortality of recently released prisoners. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2009;30(1):6–9. doi:10.1097/PAF.0b013e3181873784.

Marsch LA, Bickel WK, Badger GJ, Stothart ME, Quesnel KJ, Stanger C, et al. Comparison of pharmacological treatments for opioid-dependent adolescents—a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1157–64. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1157.

Smyth BP, Fagan J, Kernan K. Outcome of heroin-dependent adolescents presenting for opiate substitution treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;42(1):35–44. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2011.07.007.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Intramural Research Program, National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Phillips, K.A., Preston, K.L. (2013). Buprenorphine in Maintenance Therapy. In: Cruciani, R., Knotkova, H. (eds) Handbook of Methadone Prescribing and Buprenorphine Therapy. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6974-2_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6974-2_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-6973-5

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-6974-2

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)