Abstract

Scientific consensus has emerged that introducing and scaling up core interventions of a comprehensive HIV prevention program—linked with an enabling environment of laws, policies, and regulations supportive of prevention, treatment, and care—can stabilize and halt the spread of, and even reverse, the HIV epidemic among persons who inject drugs (PWID) [1–4]. Yet, the global burden of HIV and other diseases among persons who inject drugs (heroin, cocaine, and amphetamine-type stimulants) is high and growing in many regions of the world. Availability and access to evidence-based core interventions are low; profound obstacles persist, limiting the nature, scope, and quality of prevention, treatment, and care services. Despite the fact that every country reporting persons who inject drugs has made commitments to protect human rights in relation to HIV [5], many do not enforce their policies and violate the human rights of persons who inject drugs [6, 7].

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Government

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Scientific consensus has emerged that introducing and scaling up core interventions of a comprehensive HIV prevention program—linked with an enabling environment of laws, policies, and regulations supportive of prevention, treatment, and care—can stabilize and halt the spread of, and even reverse, the HIV epidemic among persons who inject drugs (PWID) [1–4]. Yet, the global burden of HIV and other diseases among persons who inject drugs (heroin, cocaine, and amphetamine-type stimulants) is high and growing in many regions of the world. Availability and access to evidence-based core interventions are low; profound obstacles persist, limiting the nature, scope, and quality of prevention, treatment, and care services. Despite the fact that every country reporting persons who inject drugs has made commitments to protect human rights in relation to HIV [5],Footnote 1 many do not enforce their policies and violate the human rights of persons who inject drugs [6, 7].

It has been estimated that there are about 15.9 million male and female persons who inject drugs (PWIDs) globally, with as many as 2.59 million PWIDs in the USA [8]. Among the 148 countries in which injecting drug use has been documented, 120 (81%) reported HIV among PWIDs in 2007. Globally, an estimated 3.0 million people who inject drugs are HIV positive, which accounts for about 10% of total HIV infections [8]. Drug use, particularly injection drug use, plays a major role in the transmission of not only HIV but also other blood-borne infections, hepatitis B (HBV), and hepatitis C (HCV), contributing significantly to the global burden of disease [9]. HBV and HIV also can be transmitted through risky sexual practices [10, 11]Footnote 2. Burden of other sexually transmitted infections (STIs)Footnote 3 is also high among persons who use drugs [15].

The proportion of persons who inject drugs and could benefit from core interventions, to those who access and receive the interventions (coverage rates), is very low [6, 16, 17]. A 2009 report describes that globally, only 26% of PWIDs were reached with HIV prevention services of any kind [18]. Fewer than 10% of all PWIDs have access to syringe and needle programs. Only 8% of opioid users have access to essential and proven effective medication-assisted treatment. Four percent of PWIDs living with HIV infection are receiving antiretroviral treatment (ART) [16, 19]. Services are even more limited for persons who inject drugs and are incarcerated—a common event for between 56 and 90% of people who inject drugs [7]. Many factors account for the gap between need and actual coverage—legal, policy, fiscal, and human resources as well as operational barriers. To a great extent, low coverage rates and high burden of disease in PWIDs reflects a country-level struggle to resolve the tension between responding with criminal justice versus a public health approach. A criminal justice approach uses punitive laws, policies, and law enforcement practices resulting in high rates of incarceration while a public health, human rights-based approach with harm reduction strategies provides for supportive laws, policies, and environment that enable PWIDs to access comprehensive, low-threshold services [20–24].

This chapter focuses on creating and implementing a new public health approach to reduce the burden of disease among persons who use drugs, and address the challenges ahead. It starts with documenting the public health and human and social consequences and costs of not acting on informed and science-based policies, and establishing programs for scaling up comprehensive HIV prevention. The next section of this chapter is a review of global, regional, and country-level epidemiological data, including a focus on the USA, and on the current status of injection drug use and the global burden of HIV and other blood-borne and sexually transmitted infections among people who use drugs. The chapter focuses primarily on low- and middle-income countries and also includes a focus on the USA and some high-income countries that have achieved high intervention coverage rates for PWIDs. The only regions of the world with increasing HIV incidence according to the 2010 UNAIDS report are Central Asia and Eastern Europe, countries with drug-driven epidemics [25].

The second section reviews some of the macro-level structural determinants—policies, regulations, and associated law enforcement practices, and high rates of incarceration of PWIDs—that shape vulnerability, risk, transmission, and country-level programmatic response to these infections. In the third section, we discuss evidence-based findings and best practices related to the prevention of HIV and other infections among PWID. This section also focuses on coverage and scaling up of HIV, Hepatitis, and STI prevention, treatment, and care for PWIDs, including new approaches to deliver services. The final section highlights the challenges ahead for a new public health approach to prevention of HIV and other blood-borne and sexually transmitted infections for persons who inject drugs. The challenges are clear.

Epidemics of Drug Use and Epidemiology of HIV, Other Blood-Borne Infections, and STIs Among Drug Users

Global Overview of Illicit Drug Use

The global scale of illicit drug use and the burden of HIV and other diseases associated with injection drug use represents a major international public health concern. The globalization of the drug trade and resulting increases in the availability of drugs due to trafficking from source countries, and navigating through and to destination countries (particularly heroin, cocaine, and amphetamines), greatly contributes to demand for these drugs in countries with high-level consumption; increasing demand for drugs in countries with historically low levels of consumption, as new trafficking patterns are established; and conditions that introduce and/or sustain HIV epidemics. HIV prevalence has been reported to follow drug trafficking patterns, suggesting that emerging trafficking routes can predict HIV spread among PWIDs [26].

Worldwide, it was estimated that between 155 and 250 million persons used drugs at least once in 2008, including 12.8–21.9 million who used opiates, 15–19 million who used cocaine, and 13.7–52.9 who used amphetamine type stimulants [27].Footnote 4 Of these, 16–38 million people were identified as problem drug users, defined as regular or frequent users of drugs who face social or health consequences because of their drug use [27].Footnote 5

There is considerable regional, country, and subnational variation in patterns of drug use (types of drugs available, drugs used, and modes of administration, e.g., smoked, sniffed, snorted, or injected), the sizes of the drug-using populations, and prevalence of use. Prevalence of drug use and demand for treatment for specific drugs are all closely linked with geographic proximity to cultivation (notably opium and coca), production, distribution, trafficking, and transit of the illicit drugs. Table 12.1 shows that the proportion of drug users varies geographically by region and by drug used. Opiate use, which consists mostly of injection of heroin, is highest in Europe, and particularly in Eastern European and Central Asian countries. Cocaine use is highest in the Americas, mostly reflecting high prevalence of use and demand (about 40% of global demand) in North America, particularly the USA [27]. In recent years, the trafficking of drugs from Mexico to the USA in response to demand has resulted in considerable violence and deaths associated with drug distribution and efforts to police and limit the supply to the USA. Finally, the highest numbers of amphetamine users are found in Asian countries. Some persons who use drugs inject amphetamine-type stimulants. In reality, a range of drugs are used by persons who inject drugs in most countries—with some users limiting their use to a single drug, and many using a range of different drugs. The use of multiple drugs in Asian countries and increasingly in Eastern European countries, particularly amphetamine-type stimulants and opiates, undermines the potential effectiveness of medication-assisted treatment of opioid dependence with methadone.

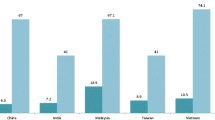

The countries with the largest estimated numbers of PWIDs are China (2.35 million in 2005), the USA (1.86 million in 2002), and the Russian Federation (1.825 million in 2007) [8].

Illicit Drug use in the USA

Drug use patterns in the USA have changed over time. New drugs have emerged, and familiar drugs such as heroin have cycles of popularity, following epidemiological curves of rising incidence and prevalence, stability, and declining incidence [28, 29]. Epidemics of heroin use were reported in the late 1940s and again in the late 1960s (with the highest incidence occurring between 1971 and 1977), followed by epidemic-level use of cocaine, which in turn was followed by the emergence of the “crack” cocaine epidemic and, most recently, epidemics of amphetamine-type stimulants. Use of heroin, cocaine hydrochloride (particularly injection use), and “crack” cocaine have resulted in upward swings in incidence of HIV and other blood-borne infections resulting from the reuse of syringes.

In the US, 21.8 million persons are estimated to use illicit substances (including marijuana) and 7.1 million drug users had a diagnosis of drug dependence in 2009 [30]. Cocaine and crack were used by 1.6 million people, while heroin was used by 200,000 people [30]. Most persons who use drugs who need treatment do not receive it. Only 10–33% of those with drug dependencies receive treatment; however, the number of people receiving treatment has increased steadily from 2002 to 2009 [30, 31].

Drug Treatment Admissions

In 2007, 1.8 million annual admissions into drug treatment facilities were reported and listed by primary substance abused. The largest percentage of admissions were for alcohol (40.3%), followed by opiates consisting primarily of heroin (18.6%), marijuana/hashish (15.8%), cocaine and crack (12.9%), amphetamine-type stimulants including methamphetamines (7.9%), and other drugs (1.4%) [32].

Treatment Admissions by Race

In the USA, drug use disproportionately impacts racial and ethnic minority populations, particularly African American men and women. African Americans make up about 12.3% of the U.S. population [33], while more than 22% of treatment admissions for heroin were among African Americans, 48.8% of smoking “crack” admissions, and 23.2% of cocaine admissions. Unlike heroin and “crack,” which are disproportionately used by African Americans, methamphetamines are used most frequently by Hispanic populations [32]. These data are limited to those in treatment and do not represent the overall drug-using population, most of whom cannot access or are not seeking treatment. This pattern of disproportionate impact of drug use on racial minorities is reflected in HIV and other blood-borne infection surveillance data, incarceration rates, and data from treatment admissions for drug dependence [34–37].

Epidemiology of HIV Among Persons Who Inject Drugs

Global Overview

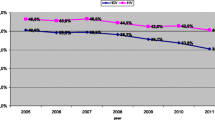

Epidemics of HIV among PWIDs have been characterized by explosive growth, sustained high prevalence, and geographic spread from the epicenter to other regions within a country over time. The number of countries reporting HIV among PWIDs, as reported earlier, continues to grow, and epidemics among PWIDs are now occurring in countries with generalized heterosexual HIV epidemics. Figure 12.1 shows the rapid increase in HIV prevalence in a number of countries, starting with the first reported epidemic in New York City; HIV seroprevalence among PWIDs in New York City increased from under 10% in 1978 to more than 50% by 1983 [38, 39]. This type of outbreak has also been documented in other countries, and more recently in Eastern Europe and Central Asia [40]. Rapid spread is associated with high-risk injection practices—primarily multi-person reuse of drug injection equipment and, specifically, HIV-contaminated syringes and needles. Not all countries with injection drug use and HIV among PWIDs experienced rapid increase in HIV prevalence. This will be discussed more fully in the section on HIV prevention.

Rapid Increase in HIV prevalence among injection drug users in 10 cities, 1977–1998 [38]. Source: Ball AL, Rana S, Dehne KL. HIV prevention among injecting drug users: responding in developing and transitional countries. Public Health Rep 1998;113(Supp 1) 170–81

Around 30% of global HIV infections outside of sub-Saharan Africa are caused by use of contaminated injecting equipment by PWIDs, accounting for an increasing proportion of those living with the virus [15]. Injection drug use is the major route of HIV transmission in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and Canada, and is driving the epidemic in parts of South and Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, and North Africa. Of the estimated three million drug users living with HIV globally, 32% live in Eastern Europe, 22% in East and Southeast Asia, 19% in Latin America, and 27% in all other regions [8]. HIV is reported in 8.74–22.4% of estimated 1.29–2.59 million PWIDs in the US. [8].

In some countries where the major mode of HIV transmission is heterosexual sex, drug use-driven epidemics are emerging. In addition to facing the enormous burden of heterosexually transmitted HIV, some sub-Saharan countries are experiencing changes in patterns of drug use, both IDU and non-IDU, which have implications for the potential spread of HIV and other STIs [41]. For example, there are more than 30,000 PWIDs in Kenya with an HIV prevalence of 36.3–49.5%, and approximately 262,975 PWIDs in South Africa with an HIV prevalence of 4.8–20% [8].Drug trafficking, specifically heroin and cocaine, to and through these countries has created and led to increased use [42, 43]. Southern and Eastern Africa currently has the second highest growth in opiate use, and Western Africa has emerged as a major trafficking route for cocaine and opiates [27].

Other changes in epidemic patterns of HIV among PWIDs have also been reported. HIV epidemics among PWIDs have high potential to spread rapidly between those who inject drugs and the wider community through sexual transmission [44, 45]. Des Jarlais and colleagues [46] report that a number of countries with historically drug-driven HIV epidemics, specifically Ukraine and Russia, are reporting increasing rates of heterosexual transmission, though this shift is most likely based on transmission from persons who inject drugs to their non-injection sexual partners. These countries also experience high HIV prevalence among overlapping high-risk populations of sex workers, men who have sex with men (MSM), and people who use drugs (injection and non-injection).

HIV in the USA

The HIV epidemic in the USA reflects the high burden of disease across most-at-risk populations—primarily MSM, with a small percentage of MSM who inject drugs, and among male and female heterosexual persons who inject drugs. HIV among PWIDs was first officially reported in the USA in 1981, but in New York it can be traced back to 1976 [39]. According to the centers for Disease Control of Prevention, of the 1.1 million people in the USA living with HIV in 2006, persons who inject drugs made up 19% (204,600) of all HIV infections. PWID accounted for 10% (4,110) of the estimated 41,087 new HIV infections in 2008 in 37 states, while PWIDs and MSM accounted for an additional 3% of new HIV infections [47]. Persons who inject drugs (40%) are also significantly more likely than MSM (35%) and persons who engage in high-risk heterosexual contact to receive a late HIV diagnosis [36]. Though HIV incidence among PWID has fallen by 80% since its peak in the early 1990s, and risk behaviors have declined, injection drug use was still the third highest reported risk factor for HIV infection in the USA in 2007 (after male-to-male sexual contact and high-risk heterosexual contact); reuse of syringes and high-risk sexual practices persist [44].

During 2004–2007, a total of 152,917 persons received a diagnosis of HIV infection in 34 states reporting data, including 19,687 (12.9%) persons who inject drugs. These data reveal, as did the data on race and drug use by treatment admissions, the disproportionate burden of disease among African Americans. African Americans accounted for 11,321 (57.5%) of HIV-infected PWIDs, while whites accounted for 4,216 (21.4%), and Hispanics or Latinos for 3,764 (19.1%) [36].

Epidemiology of Viral Hepatitis (HBV and HCV) and Injection Drug Use: Global and U.S. Overview

In addition to HIV, persons who inject drugs are also at high risk from other blood-borne infections, including HBV and HCV, through the sharing of injecting equipment (needles and other injection-related equipment such as cotton filters, water, and spoons/cookers) [48]. HCV is the most prevalent infection among PWIDs and injection drug use is the primary mode of HCV transmission in the developed world [49–51]. A growing body of evidence demonstrates transmission of HCV through high-risk, often traumatic, sexual practices among heterosexuals, HIV-infected individuals, and MSM where non-injection drug use is also occurring [13, 52, 53]. HBV is approximately 10 times more transmissible than HCV, and 20 times more transmissible than HIV [50].

Approximately 180 million people in the world are living with HCV; approximately 90% of all new infections are attributed to PWID [54]. Considerable variation in HCV prevalence exists within and across and regions [55]. HCV prevalence has been reported among PWIDs in 57 of the 131 countries with PWIDs. In 9 of these countries, HCV prevalence was estimated at between 20 and 50%; it ranged between 50 and 90% in 31 countries, with prevalence estimates of anti-HCV among PWIDs at least 90% in 17 countries. HIV/HCV coinfection among PWIDs has been found in 16 countries reporting PWID [56, 57]. Estimates show that at least 90% of HIV cases were coinfected with HCV in eight of these countries (China, Poland, Puerto Rico, Russia, Spain, Switzerland, Thailand, and Vietnam) [56]. Global prevalence rates of HBV among PWIDs are not available, however site-specific surveys show HBV prevalence among cohorts of PWIDs at 50–84% in the USA [58], 27% in Wales [59], 55% in Georgia [60], and 53.3% in Switzerland [61].

At the end of 2005, there were 3.2 million people in the USA living with chronic hepatitis C. Similar to reports of HIV incidence among PWIDs, HCV incidence has been on the decline since the late 1980s reflecting increased awareness and access to needle and syringe programs. In 2007, there were 17,000 new infections, and injection drug use accounted for 48% of the cases [37] It is estimated that 50–90% of HIV-infected PWIDs are also infected with HCV [62]. It has been estimated that between 48,014 and 86,424 noninstitutionalized PWIDs are living with both HIV and HCV [12].

An estimated 800,000 to 1.2 million people in the USA are infected with HBV. In 2007, it was estimated that 43,000 new HBV infections occurred in the USA [37]. Though HBV incidence in the USA has declined in the last decade, high rates of HBV infection continue to occur among persons in identified risk groups, including PWIDs. In 15% of the cases, PWID was reported as a risk factor among those whose risk information was available. HBV rates in 2007 were highest among non-Hispanic blacks (2.3 per 100,000) [37].

Epidemiology of STIs (Syphilis, Gonorrhea, and Chlamydia) in Drug-Using Populations

Globally, surveillance data on sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are limited, and data on STIs among drug-using populations are limited to site-specific surveys. However, meta-analyses on STIs in drug-using populations reveal a high burden. Semaan and colleagues [63] found that in the USA, 1–6% of drug users are infected with syphilis, 1–3% with gonorrhea, and 2–4% with chlamydia, with variations in rates based on race, sex, age, drug-using behavior, and region. Without straightforward comparability across figures, rates of STIs among people who use drugs appear disproportionately high compared to rates among the general population demonstrates [52, 64].Footnote 6

Among persons who use drugs, the prevalence of chlamydia was lower among whites (4% among white males and 6% among white females) and older drug users (2% among <25 years old). It was higher among female “crack” users (14%), those who trade sex (8%), and those with more than five partners in a period of 4 weeks (9%). Studies conducted outside the USA reported rates similar to those in USA: 3% in Quebec City, Canada, 2% in Chiang Mai, Thailand; 6% in Melbourne, Australia [63].

Coffin and colleagues [65] found similar variations in syphilis prevalence among drug users in low- and middle-income countries by sex, risk behaviors, and region. In their review, an overall prevalence of 11.1% was reported while median syphilis prevalence was 4.0% among males and 19.9% among females [65]. Female drug users are consistently at higher risk for and have higher rates of STIs. Sex work could explain the relationship between female sex and syphilis prevalence as high prevalence was observed among female sex workers and their clients (10.8–64.7%) [65–69].

Risk Factors for STIs Among Persons Who Use Drugs

Overlapping and multiple risks are associated with drug use and STI transmission among people who use drugs, their partners and the larger community. Risk for STIs varies by the drug used, reflecting the pharmacology of the specific drug (cocaine hydrochloride, “crack,” amphetamine-type stimulants, heroin, and other opioids), and the setting or context in which these drugs are used [70, 71]. While heroin is associated with reduced sexual arousal and activity, cocaine and amphetamine use has a strong relationship with STI risk behaviors such as increased impulsivity, unprotected sex, “rough” sex, multiple partners, and group sex [72–75]. “Shooting galleries,” crack houses, and bathhouses are venues where overlapping high-risk groups (drug users selling sex and/or money for drugs, sex workers selling sex to drug users, and men who have sex with multiple male partners and use amphetamines) congregate and engage in sex and drug use, increasing the risk for sexual transmission of infections [76–81].

The co-occurrence of male-to-male sexual activity, use of amphetamine-type stimulants, and STI risk behaviors has been well documented. Use of amphetamine-type stimulants, such as methamphetamine, is prevalent among some MSM communities [82–85], and are often used in sexual contexts to prolong pleasure and reduce inhibitions [86, 87], resulting in behaviors such as unprotected sex, multiple sex partners, and subsequent STI transmission [73, 88].

The exchange of sex for money and/or drugs often co-occurs with drug use among female drug users and results in high STI rates [89, 90]. Female drug users also play a key role in the transmission of STIs by creating a bridge between smaller populations with high prevalence of STIs/HIV and drug use to the larger general population via heterosexual sex and often, commercial sex [81, 91]. The relationship among crack, sex work, and STIs in the USA serves as an example [92, 93]. An association between crack use and risky sexual behaviors has been reported. Beginning in 1986, the rise in crack cocaine use coincided with the rise in primary and secondary syphilis among African Americans. In Baltimore, primary and secondary syphilis cases increased from 144 in 1993 to 669 in 1997 and were attributed to crack cocaine use and the exchange of sex for crack [94]. When crack enters a community, the number of sex sellers increases, therefore driving down the price of sex, often to the price of a “hit.” The sex economy is elastic, meaning that demand increases as price decreases so the decreased price leads to more buyers of sex work. High competition among sex workers gives the consumer the upper hand to insist on riskier sex acts or further lower the price causing the sex worker to take on more clients [95, 96]. Additionally, consumers of sex work often come from outside the drug-using communities thereby creating a bridge for disease transmission beyond persons who use drugs and their regular sex partners.

Macro- and Micro-Environmental Factors and Vulnerability to HIV and Other Blood-Borne and Sexually Transmitted Infections

Many factors help explain why the burden of disease, especially HIV, is high and growing among PWIDs in many developed, low-, and middle-income countries. Rhodes and colleagues have developed a risk environment framework that focuses on the overlap and interaction of social, structural, and environmental factors, categorized as either macro- or micro-environmental factors that influence vulnerability and risk for HIV acquisition and transmission [97, 98].

High-risk injecting and sexual behaviors drive the spread of these infections and are affected by a number of structural factors, including economic, political, legal, social and policy environmental factors [97, 99]. This section briefly reviews some of the macro- and micro-environmental factors that shape vulnerability, risk, and transmission for persons who use drugs. Among the many factors increasing vulnerability of PWIDs and risks for spreading HIV and other blood-borne and sexually transmitted infections are globalization of the drug trade, restrictive laws and punitive drug policies, incarceration of persons who inject drugs, and gender norms around female PWIDs. Today, there is increasing recognition that health should be the core focus of drug policy; drug dependence is a treatable health problem; treatment and other alternatives are more effective for health and social outcomes than incarceration; universal access to drug treatment should be integrated into the health care system, and the human rights of persons who inject drugs have to be protected by ensuring equitable and voluntary access to services that can reduce harm and prevent HIV, morbidity, and mortality associated with drug use [6, 27].

Globalization of the Drug Trade

Though the supply of opioids and cocaine (the two main problem drugs) has declined, the amount produced and trafficked remains substantial. Along with reductions in cultivation, production, and use of heroin and cocaine, there has been an increase in the production and use of synthetic amphetamine-type stimulants and prescription drugs [27]. Drug markets are dynamic and evolve, and the availability of a range of drugs to meet demand is a factor. Crucial to the health of PWIDs is the resolution of multi-sector tensions and nonaligned policies between criminal justice agencies in governments that favor interdiction to reduce supply and demand, laws and incarceration resulting from the possession of drugs, and the public health sector approach aimed at minimizing harm to PWIDs [20, 21].

Cocaine is produced largely in the Andean region of South America, which supplies the USA, the largest market. Recently, cocaine has been trafficked through and to Africa, notably West and Central Africa [22]. A high demand for amphetamine-type stimulants in the USA, particularly methamphetamines, reflects the drug’s primary trafficking route to the USA through Mexico and a co-occurring methamphetamine epidemic in Mexico [22, 100]Footnote 7. Beyrer and colleagues reported that overland heroin export routes have been associated with co-occurring epidemics of injecting drug use and HIV infection in three Asian countries (India, China, and Myanmar) and along four trafficking routes: from Myanmar to cities in China, Laos, and Vietnam [26]. Outbreaks of injecting drug use and HIV in Myanmar, India, China, and Vietnam have been associated with Burmese and Laotian overland heroin trafficking routes. For the past 6 years, production has been declining in Myanmar and increasing in Afghanistan where, in 2008, about 82% of the opium was produced. With the trafficking from Afghanistan, increases in injection drug use and the associated spread of HIV have been reported in that region [101, 102]. There is considerable concern today regarding newly established cocaine and opiate trafficking routes, mostly through Africa, as countries in the region are reporting increased drug use, including injection drug use and HIV [103–105]. Only recently have some of these countries in sub-Saharan Africa been reporting use of cocaine (mostly crack) and heroin, injection drug use, high-risk sexual practices, and HIV infection among injection and non-injection drug users. This could create a second-wave epidemic of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in countries currently experiencing enormous burden from heterosexually transmitted HIV.

Country-Level Laws and Drug Policies

In many countries drug control laws and policies are based on reducing supply and demand of drugs through interdiction, methods that often translate into policies that emphasize incarceration and punishment of drug users for possession and use, rather than facilitating access to treatment services. Drug users often report harassment by law enforcement staff, compulsory detention, high incarceration rates, fears of being arrested, stigma and discrimination, delayed or nonuse of health services by drug users, and interference with maintaining their ARV regimens [21, 106, 107]. More than 50 countries have compulsory treatment for people who use drugs and/or the death sentences for drug offenses [6]. Public health approaches provide an alternative to, or complement, drug control measures. For example, harm reduction interventions, including needle and syringe programs, and voluntary medication-assisted therapy (MAT) programs using methadone and/or buprenorphine, can prevent transmission of HIV, other blood-borne infections, and associated morbidity and mortality [19, 108].

Though a number of countries have changed laws and policies to support harm reduction programs, many countries maintain drug paraphernalia laws that prevent drug users from accessing clean needles.Footnote 8 [109]. Some countries forbid the use of medication assisted therapy (particularly methadone treatment).Footnote 9 Even in many countries that have made considerable progress in changing their laws and policies to create an enabling environment for the introduction and scaling-up of harm reduction services for PWIDs, tensions between drug control and public health approaches continue to occur, limiting access and support for services [110].

Recognition is growing that drug control policies to reduce the supply of illicit drugs and criminal justice approaches to responding to the needs of drug users have in many instances increased the marginalization of drug users and diminished the capacity of countries to offer treatment to those who need it most [22].

In U.S. drug policy, a repeated pattern of passing laws after new epidemics of drug use have emerged has resulted in increased incarceration rates for drug users. Each of the U.S. drug epidemics described in the earlier section (heroin, cocaine, crack, and ATS) resulted in increased media and political attention, and the introduction of harsher legislation for drug users that favors incarceration over treatment for drug dependence. Since 2009, this approach has been under review, and policy debate has seen a shift from a criminal justice approach to responding to drug use as a public health issue [111].Footnote 10 The criminal justice approach favors the investment of resources in public security, drug control activities, and law enforcement rather than in public health, which focuses on drug dependence treatment and the prevention and treatment of other drug-related health problems, including HIV infection [106].

Drug Use and Incarceration: A Global and U.S. Overview

Many studies report injection drug use in prisons, along with a high prevalence of both HIV and HBV, and evidence of HIV and HCV transmission among incarcerated populations [7, 55, 112]. Studies in a range of countries reveal that between 56 and 90% of PWIDs have been incarcerated, and it is estimated that 10–48% of male prisoners and 30–60% of female prisoners are drug users or drug dependent [7, 113].

At the end of 2007, the USA reported 1,595,034 persons incarcerated, more than any other country in the world. Drug-related offenses accounted for 49% of the growth in the prison population between 1995 and 2003 [114], an alarming figure as increases in incarceration rates correspond with increases in new AIDS infections [115]. Of those incarcerated, 38.2% were non-Hispanic black, 34% were white, 20.8% were Hispanic, and 7% were of other races [116]. Non-Hispanic blacks make up approximately 12–13% of the population [33], yet they make up just under 40% of those arrested for drug violations and 53% of those sentenced to prison for a drug offense [117]. Non-Hispanic blacks make up more than 80% of the defendants sentenced for crack offenses [118]. These data highlight again how drugs disproportionately affect minorities. The number of non-Hispanic black persons incarcerated for drug offenses in state prisons had fallen from 145,000 in 1999 to 113,500 in 2005, a 22% decline. During this same period, the number of white drug offenders increased 43%, from about 50,000 to more than 72,000 [117].

Data on drug use patterns of incarcerated populations in the USA, dating back to reports in 2004, reveal that in the month before the criminal offense was committed, cocaine/crack was the most frequently reported drug used (21% for state prisoners and 18% for federal prisoners) [119]. Stimulants were used by 12.5% of state prisoners and 11% of federal prisoners in the month before the offense was committed. Eight percent of the state prisoners and 6% of the federal prisoners used heroin and other opioids in the month before the offense.

Drug use within prisons is common [7]. Many people who use drugs within the community where they live continue their drug use once imprisoned, although the prevalence and frequency of drug use tends to decline during the period of incarceration. Prison is also a setting for drug initiation among non-drug users as they are exposed to drug-using situations, which may result in the initiation and continuation of drug use after their release. Prisons pose a high-risk environment for injecting drug use. The lack of sterile injecting equipment, limited access to prevention and treatment services, overcrowding, and lack of privacy result in very high-risk injecting practices. In particular, sharing of injecting equipment is common among a population where HIV, viral hepatitis, and other blood-borne infections are already high [7, 55].

Most PWIDs return to their respective communities after their sentences. A majority of those who inject in prison report sharing syringes, and high-risk sexual behavior is common among drug users while incarcerated [7, 120, 121]. The return of previously incarcerated PWIDs to home communities has significant implications for the spreading of HIV and other blood-borne and sexually transmitted infections [122].

Prevention of HIV, HBV, HCV, and STIs

For more than 25 years, scientific evidence has been accumulating that comprehensive HIV prevention programs can help avert, halt, and reverse HIV epidemics among PWIDs [1–3, 135]. Early in the HIV epidemic among PWIDs, a number of cities (Glasgow, Scotland; Lund, Sweden; Sydney, Australia; Tacoma, Washington; and Toronto, Canada) implemented effective programs to prevent significant HIV epidemics from emerging and maintained low and stable HIV seroprevalence rates in the population of PWIDs. Core multi-component prevention interventions—community-based outreach, large-scale provision of sterile injection equipment through syringe exchange programs, pharmaciesFootnote 11 and, in one city, large-scale drug dependence treatment—can reverse and contain epidemics among PWIDs, reducing incidence and prevalence [46]. New York City, with the largest epidemic of HIV among PWIDs in the world, legalized and implemented a large-scale expansion of syringe exchange programs in the early 1990s, including outreach and testing and counseling services [136]. Hartel and Schoenbaum [137] reported that HIV among injecting heroin users in the Bronx, who were in methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) in the late 1970s when the epidemic began, had a lower prevalence rate (34%) than those who enrolled in MMT in 1980 and 1984 (44%); the HIV prevalence rate was highest for PWIDs who enrolled after 1985 (53%).

Over time, evidence continues to accumulate that these interventions—outreach, needle and syringe programs (NSPs) and MAT—singularly and in combination affect risk behaviors and can reduce incidence and prevalence of HIV among persons who inject drugs. Community-based outreach provides a range of services to persons who inject drugs in their natural environments. Outreach workers in the community in fixed and/or mobile sites and street locations provide access to risk-reduction information, enable people who use drugs to reduce their drug use and needle-sharing behaviors by providing alcohol wipes, bleach, water, condoms, and referral to services [2, 138]. Some outreach programs train PWIDs in overdose prevention—teaching them how to administer naloxone—and some outreach workers provide sterile needles and syringes. Outreach has been demonstrated to enable PWIDs to access the means to reduce their risk behaviors.Footnote 12 Through referral mechanisms, outreach increases the likelihood that persons who inject drugs will have access to a range of other complementary services essential to reduce risk of acquisition and transmission of HIV and other blood-borne infections [138]. The evidence is strong that NSPs result in reduced risk behaviors, lower HIV prevalence, greater use of services, and, importantly, reduced injection drug use [139]. Consistent findings from evaluation studies of NSPs reveal that they increase the availability of sterile injection equipment, reduce the number of contaminated needles in circulation, and reduce the risk of new HIV infections [1, 140]. Des Jarlais and Semaan [136] reported that most NSPs provide a range of other services, including referral to drug dependence treatment programs, specifically MAT and other programs. Medication-assisted treatment with methadone or buprenorphine has been shown to be effective for opioid dependence, reducing risk behaviors related to injection drug use, preventing HIV transmission, and improving PWIDs’ adherence to antiretroviral therapy [3]Footnote 13. In a recent review of evidence on MMT, the Institute of Medicine concluded, based on randomized clinical trials and a number of observation studies, that persons receiving MAT report reductions in drug-related risk behaviors, including the frequency of injecting and sharing equipment [142]. Metzger found that persons who inject drugs and remained in methadone treatment had a lower HIV incidence than those who were not enrolled in MAT [143]. Other interventions, not unique to persons who inject drugs, are also now part of a comprehensive HIV response, including ART (see Box 12.3).

The core interventions discussed above and listed elsewhere in the text are potentially important strategies for limiting the spread of HCV and HBV. Specifically for HCV, NSPs with risk reduction emphasis on not sharing or reusing injection equipment, MAT, and other drug dependence treatment, condom programming and safer sex practices and prevention and treatment of STIs are effective. HCV can be transmitted sexually, particularly in the context of HIV coinfection [144]. Because background prevalence is much higher for HCV than HIV, and it is more infectious, though it varies regionally, the need to reach more at-risk populations earlier is of critical importance. For HBV, vaccination is an additional intervention that can have an impact on transmission and interventions to increase safer sex practices for PWID, MSM, and those who have not been vaccinated for hepatitis B [52]. Most important is that NSPs and outreach provide information about HCV and ways to prevent transmission by providing sterile cotton swabs, alcohol wipes for cleaning injection sites, sterile water, cookers, and other disinfection supplies and skills to promote adherence [140]. Evidence suggests NSPs have less impact on the transmission and acquisition of HCV than on HIV, though one study found that NSPs had a significant effect on decreasing HCV and HBV acquisition [145]. Substance dependence treatment has been shown to reduce the incidence of HCV [51]. In a study in Seattle, those who remained in MMT longer had a lower HCV prevalence than those who interrupted or dropped out of treatment [146].

In addition to MAT for the treatment of opioid dependence, non-pharmacologic therapies are effective strategies at treating cocaine and amphetamine dependence and preventing HIV, hepatitis, and STI risk behaviors associated with drug use. It is important to consider these strategies in addition to MAT, as the number of cocaine, amphetamine, and poly-drug users grow [27, 147]. In addition, many opioid users engage in cocaine use while on drug treatment [148, 149]. Effective psychosocial interventions including cognitive-behavioral therapies and contingency management are currently available to treat cocaine and methamphetamine dependence [150, 151] and pharmacologic therapy may be available in the future [152, 153].

Combination Interventions

Combination prevention programs consist of a mix of structural, biomedical, and behavioral interventions. Findings from recent mathematical modeling studies reveal that combination interventions—NSPs and MAT (if coverage reaches 50% of the persons who inject drugs)—in 5 years could lead to a 20% reduction in HIV incidence depending on the setting [19]. And, when ART is combined with MAT and NSPs, reaching 50% of the persons who inject drugs and are HIV positive, after 5 years the incidence will be a 50% median reduction of 29%. Strathdee and colleagues [108] modeled changes in risk environments in regions with different types of HIV epidemics among persons who inject drugs. Consistent with the work of Degenhardt and colleagues [19], they report that by reducing unmet needs by 60% in MAT, NSPs, and ART, there are reductions in HIV prevalence ranging from 30 to 41% over 5 years. They also reported that structural level changes like changing laws in Kenya to allow MAT in public clinics and needle syringe programs or reducing changing police practices related to harassment and violence in Odessa, Ukraine, can further contribute to reducing HIV incidence.

Structural Interventions

Optimizing the impact of core interventions to prevent the further spread of HIV requires implementation of structural interventions to help create an enabling environment supportive of an effective HIV response in a range of settings (community, clinics, jail/prisons, and other detention settings) [55].

Structural interventions seek to create contextual changes in the social, physical, economic, and political environments to remove or reduce barriers that contribute to HIV/AIDS vulnerabilities and risks, and that impede access to services, and to create an enabling environment supporting implementation with evidence- and human rights-based laws, policies, and regulations, facilitating the scaling up of prevention interventions. The rationale for the potential value of structural interventions is clear [19, 97]. Laws, policies, regulations, resulting stigma and discrimination, incarceration without legal rights and violations of human rights to health are among the factors that account for the limited availability, inaccessibility, low coverage, and continuing high burden of disease. Among the structural strategies most often mentioned are efforts to improve the legal environment—laws and policies, law enforcement, and legal clinics—for persons who inject drugs and who are arrested. These reforms could include laws promoting protection from discrimination, gender-based violence, human rights violations, and laws to enable harm reduction services to operate effectively without impunity [23]. Other structural interventions and potential effects operating at macro and micro levels of the physical, social, economic, and policy environments described by Degenhardt and colleagues [19], can include scale-up of needle and syringe provision and legal reform enabling protection of drug-user rights.

HIV, HBV, and HCV Prevention in Prison and Other Closed Settings

Jurgens, Ball, and Verster [7] reviewed the effectiveness of interventions to reduce PWID risk behaviors and HIV, HBV, and HCV transmission in prison settings. Evidence of injection and high-risk sexual practices in these settings has been referred to earlier. There is substantial HIV transmission through drug use in prisons, and many studies have also reported HCV outbreaks among incarcerated populations [21]. More prisons are now recognizing the epidemiological realities of transmission in these settings and have begun to introduce core interventions; most countries, however, do not provide these services. NSPs have been introduced in more than 50 prisons in 12 western and eastern European and central Asian countries. In some countries, only a few prisons have NSPs, while in Kyrgyzstan and Spain, NSPs in prisons have been rapidly scaled up. With the exception of one study, evidence demonstrates that sharing of injecting equipment either stopped after implementation of the NSPs [154, 155] or substantially declined [156–158]. PWIDs in Moldovan prisons with NSPs also reported fewer incidents of sharing injecting equipment [159].

Since the early 1990s, there has been a marked increase in the number of prison systems providing opioid substitution therapy (OST) to prisoners. Jurgens, Ball, and Verster (2009) found that in all studies of prison-based MMT programs, prisoners who inject heroin and other opioids and who receive MMT inject substantially less frequently than those not receiving this therapy [7, 160–163]. Access to OST in prisons also reduces injection risks and syringe sharing [164]. Some countries, Spain in particular, has scaled up NSPs and OST in prisons and the seroconversion rates for HIV and hepatitis C virus have decreased substantially.

Prevention and Treatment of HCV

HCV is more infectious than HIV and more prevalent, especially among younger injectors, with modes of transmission including reuse of contaminated syringes, needles, and other injection equipment [12, 62, 165]. Due to shared risk factors and prevention strategies between HIV and hepatitis, HCV prevention is critical to an effective HIV prevention strategy among PWIDs. Modeling studies demonstrate that HIV and HCV prevalence among PWIDs are proportional and that reducing HCV prevalence below a threshold of 30% would substantially reduce any HIV risk and likely make HIV prevalence negligible [166].

Edlin and colleagues [167] have outlined and discussed the strategies for prevention and treatment of HCV. These include strategies for primary prevention (preventing exposure) by reducing injection drug use through evidence-based substance use prevention and expansion of substance dependence treatment. Most critical is preventing and/or reducing transition from non-injecting drug use to injecting drug use [168]. Edlin describes options in secondary prevention (preventing infection) of HCV transmission among PWIDs by providing access to sterile syringes and other injection equipment, repeal of paraphernalia and syringe prescription laws, establishment of syringe exchange and distribution programs, education of physicians and pharmacists to help PWIDs gain access to sterile injection equipment, community-based outreach to PWIDs, and client-centered HCV counseling and testing [169]. For tertiary prevention (preventing disease) and reducing liver diseases in the infected person, Edlin identifies potentially effective strategies, including medical treatment for HCV infection, integration of medical and social services, and provision of services to incarcerated populations [77]. Most important is that needle and syringe exchange programs and outreach provide information about HCV and ways to prevent transmission by providing sterile cotton swabs, alcohol wipes for cleaning injection sites, sterile water, cookers, and other disinfection supplies and skills to promote adherence [140]. Evidence suggests NSPs have less impact on the transmission and acquisition of HCV virus than on HIV, though one study found that NSPs had a significant effect on decreasing HCV and HBV acquisition [145]. Treatment for drug dependence has been shown to reduce the incidence of HCV [51]. In a study in Seattle, it was found that those who remained in MMT longer had a lower HCV prevalence than those who interrupted or dropped out of treatment [146].

STI Prevention Among Persons Who Use Drugs

Historically, prevention for drug users has centered on injection-related risk, overlooking the fact that drug users are at high risk for sexual transmission of infections, including HIV and STIs. STI control among drug users is an important public health strategy as the presence of an STI infection increases susceptibility and infectivity of HIV [170–173]. HIV positive women are significantly more likely to be coinfected with multiple STIs compared to those who are HIV negative [174]. Presence of an STI may also facilitate HCV transmission [175].

STI control is a public health priority for drug users for several reasons. First, it has implications for persons who use drugs as well as those who do not use drugs but may have sex with drug users [176]. As STI treatment decreases transmission, identification of STI cases among drug users would give treatment options to these individuals and would help reduce the spread of infection to others, both inside and outside of this population [177]. Since drug users face many individual and provider-level barriers to accessing STI prevention and control services, they are likely to go untreated and further transmit infections inside their networks. Clinical management of STIs also leads to reduced incidence of HIV over time [178], and provides an opportunity for health care providers to assess drug use as a risk behavior that can lead to vaccination for hepatitis A and B, screening for viral hepatitis, STIs and HIV, and appropriate treatment services for these infections along with linkages to other prevention strategies for drug users, including needle and syringe programs and drug dependence treatment [52].

As more biomedical interventions become available for the prevention and control of STIs, attention has shifted to improving health care-seeking behaviors and the behaviors of care providers [179]. Individual-level interventions can modify drug use or STI risk behaviors [180] but structural changes are also required for large-scale impact [181]. For example, routine STI screening and treatment at drug treatment admission and other primary care venues commonly frequented by drug users would facilitate access to these services [95, 182]. According to CDC, drug use is a risk factor for gonorrhea among women and routine screening is recommended [52]. STI infection is a marker for high-risk sexual behaviors, so screening for these infections presents an opportunity to provide risk reduction counseling and other effective behavioral interventions.

Gender Norms Around Female PWIDs

HIV infections are rising among female PWIDs in Asia, Eastern Europe, and other countries [123, 124] as females who use drugs face a greater risk of blood-borne and sexually transmitted infection [125]. Female PWIDs often rely on male partners to initiate drug use, procure drugs, and inject them with drugs [126–129]. As drug-using practices often follow social norms, women are more likely to use contaminated equipment as they inject after men, and refusal to use drugs or share injecting equipment results in increased risk of physical in sexual abuse, further increasing likelihood of infection [127, 130]. As stated earlier, sex work is common among females who use drugs, making them more vulnerable to infection [131].

Women who inject drugs face additional barriers to prevention and treatment services such as childcare duties, lack of power to negotiate service use and lack of access to resources [129, 132]. Men are the primary recipients of these interventions in many settings [132]. Despite evidence of their efficacy, drug treatment, harm reduction, and HIV prevention programs for women who use drugs are under-funded, and the programs that do exist rarely address intimate partner and sexual violence, reproductive health, empowerment strategies, and other risk factors among women who use drugs [133]. Provision of low-threshold services increases uptake among women and availability of gender-friendly services that include flexible hours, childcare services, social and psychological support, and programs for drug-using sex workers will further fill the coverage gap [132, 134].

Organizing and Delivering Core Intervention and Other Health Services to Persons Who Inject Drugs

New public health approaches in organizing and delivering services will require changes in their law enforcement approaches to injection drug use and HIV to be effective and have an impact on the epidemic.

Availability and Coverage of Core Interventions

Of the 151 countries reporting injection drug use, NSPs are available in 82 countries, while only 10 countries have NSPs in prisons [55]. It is estimated that about 8% of PWIDs accessed an NSP at least once in the past 12 months, and fewer than 5% of injections were covered by sterile syringes. In the 16 countries with PWIDs in Eastern Europe, it is estimated that there are 9 syringes distributed per PWID per year. The number is highest in Australia and New Zealand (213/year per PWID), comparatively high in Central Asia (92/year per PWID), and relatively low in the USA and Canada (23/year per PWID) [17]. For OST, available in 71 countries, which covers 65% of the estimated population of persons who inject drugs, only 8 PWIDs per every 100 were receiving OST. Again, there is considerable range by region with very low rates in Central Asia and Eastern Europe—about 1 per 100 PWIDs, about 4 per 100 PWIDs in East and Southeast Asia, highest in Western Europe (61 per 100 PWIDs), and much less in the U.S and Canada (13 per 100 PWIDs) [17]. The same pattern prevails for ART coverage rates. In a limited number of countries reporting coverage rates for ART among persons who inject drugs, only 4 of every 100 HIV-positive PWIDs who were in need of ART were receiving it [19].

Barriers to Introducing and Scaling Up Services

There are many reasons for low coverage rates, including cultural, legal, policy, regulatory, technical, fiscal, human resource constraints, and operational barriers, and attitudes and beliefs of service providers. These factors are obstacles to introducing, scaling up and implementing innovative strategies to organize and deliver services [16, 55].Footnote 14 In many countries, persons who inject drugs are required to be registered by name and with law enforcement. This information is often shared with health providers before they are eligible for services. Mimiaga and colleagues [183] report that in one Eastern European country, harassment and discrimination by police with threats of arrest, and the need to bribe police to avoid arrest are major barriers to adherence to MAT and ART. Laws that criminalize nonmedical use of syringes, along with punitive laws for possession of small amounts of drugs, law enforcement harassment of PWIDs, detention without due process and subjecting persons who use drugs to non-evidence-based treatment interventions create obstacles to implementing and scaling up interventions and reducing vulnerability to HIV and other blood-borne and sexually transmitted infections. Carrying condoms is often used as evidence by law enforcement of engaging in sex work [184]. The public health consequences can be observed in high incarceration rates, unavailability of services, low and often delayed utilization of services, and limited progress in the prevention of HIV, hepatitis, and STIs.

Policy and service providers’ personal beliefs affect the availability and quality of services. Despite evidence from neurosciences that drug addiction is a chronic and relapsing condition that is treatable, like other diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, controversies continue relative to the treatment of addiction and providing NSP services [139, 140, 185]. Medication-assisted treatment consistently has been proven to be an effective treatment for opioid addiction and the prevention of HIV. As more PWIDs access and remain in MAT, less crime is committed and fewer drug-related arrests are conducted, meaning fewer criminal justice costs. In addition, the demand for drugs is reduced, and less money is spent on illegal drugs, meaning less money in the informal market [186]. However, myths persist that providing medication such as methadone is substituting one addiction for another, rather than a treatment.

Coordination and Integration of a Comprehensive Package of Interventions to Address Needs of Persons Who Inject Drugs

It is critically important that all public health services or facilities that have contact with persons who inject drugs have the capacity to provide a full range of integrated, colocated direct services and/or linked referrals to other services [187]. The rationale for the recommendation is clear. Persons who use drugs are at increased risk for multiple comorbid conditions, including problems associated with drug use, such as addiction and mental health issues; multiple infections, such as HIV, STIs, and hepatitis; and adverse social conditions, such as stigma, poverty, and incarceration [188–191]. Additionally, persons who use drugs are less likely to use health services due to fear of arrest or discrimination, exacerbating negative health outcomes [97, 192, 193]. Integration of prevention, care, and treatment services for persons who use drugs addresses both comorbidities and low service utilization. Ideally, integrated services are colocated and share client records to increase efficiency, access to services, the level of prevention and care for clients, and reduce costs. Services can also be integrated through a system of coordinated referrals. Programs that have provided integrated services for persons who use drugs report successful outcomes including increased testing rates, medication adherence, entry into drug treatment services and attendance of PWID at services [194–197]. And these services should be offered in multiple venues including prisons, in the community, and a range of public health clinics and other facilities. The services should include priority interventions for persons who inject drugs—NSP, MAT, and ART—sexual risk reduction services and others that include screening, risk reduction and treatment for prevalent and co-occurring conditions. Not only can these services reduce burden of disease in individual drug users and their networks of sex- and drug-using partners, they also serve as an entry point into other prevention and treatment services specific to drug users, such as syringe exchange and drug treatment. Health services in communities where drug use takes place can assess patients for drug use. In addition to prevention strategies specific to persons who use drugs, members of this population also benefit from access to health interventions such as vaccination for hepatitis A and B, and screening and treatment of HIV, STIs and hepatitis (see new CDC guidelines: www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/) using standardized assessment tools, and providing relevant linkages as necessary [52].

Low Threshold Services

According to a report from the Open Society Institute (OSI), low threshold programs are flexible in their organization, delivery of services and eligibility requirements to access services [198]. The overall objective is to make services available to the greatest number of persons who inject drugs and rely on strategies that recognize that these populations are often hard to reach and retain in services. Colocation and integration of services can be effective, as referenced earlier; however, the extent to which this new service delivery strategy works depends on adopting principles related to low threshold programs. The list that follows is illustrative and not exhaustive, and provides examples of strategies that can remove barriers and expand availability and utilization of services. Some overarching low threshold principles include not restricting eligibility for services based on current drug-using practices or not requiring persons who inject drugs to have failed other “treatment interventions” (detoxification in detention centers); active or previous injection drug use should not be a reason not to provide ART; ART should not be dependent on enrolling in MAT (often not available); and access to ART should not require “proof” that PWIDs can be adherent with the prescribed MAT regimen.

All who seek treatment should be eligible. As reported by OSI, some specific low threshold strategies for MAT include quick service on demand and without complex paperwork, no waiting lists, service delivery by medical and nonmedical staff, limited or no urine screening without being used for disqualification from the program, abstinence from drugs not required, treatment by prescription (both buprenorphine and methadone), no registration of users, no biological testing, no requirement for any type of counseling or directly observed dose-taking before beginning unsupervised administration, flexible eligibility requirements, treatment in prisons, and take-home doses [198]. For MAT and other services, most critical is a nonjudgmental harm-reduction philosophy that does not insist on complete abstinence from drug use. Also important is reducing operational constraints, such as hours of operation, location of facilities, costs for services and ensuring multiple models of service availability in multiple venues. For NSPs, OSI reports that this means multiple service delivery models and maximizing the number of needles and syringes distributed by supporting secondary exchange of syringes, and with no limits on the number of syringes to be distributed. Other strategies that will contribute to coverage and effectiveness include ensuring there are no stock outs of commodities like syringes and needles, and that the types of syringes and needles distributed reflect the needs of the persons who use drugs. Ensuring that services are responsive to PWIDs requires that these persons participate in planning, program development and implementation [6].

Public Health Role of the USA

The USA plays an important role on the issues mentioned above through its international influence on drug control policies related to reducing supply and demand for drugs and protecting the safety and public health of persons who inject drugs, through their financial and technical support to the Global Fund, and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) program. PEPFAR provides technical and fiscal resources to countries with HIV epidemics, including those with concentrated epidemics of HIV among persons who inject drugs, and countries with expanding rates of injection drug use and HIV among persons who inject drugs [199]. In 2010, the USA issued a new drug control strategy through the Office of National Drug Control Policy, a new domestic HIV/AIDS policy through the Office of the National AIDS Policy in the White House, and policy and program guidelines through PEPFAR [200–202]. Implementing evidence-based law enforcement strategies—scaling up and increasing access to treatment for addiction, integrating addiction services into the health system with support through health services, recognizing and acting on the public health consequences of use of drugs, such as overdose deaths and HIV/AIDS, and recognizing the evidence supporting interventions in the comprehensive package of services—allows for better coordination and collaboration with the PEPFAR program.

On July 10, 2010, PEPFAR released a revised technical guidance document titled Comprehensive HIV Prevention for People Who Inject Drugs (www.pepfar.gov).Footnote 15 This document affirmed PEPFAR’s support for comprehensive, evidence-based, and human rights-based HIV prevention programs for persons who inject drugs. Along with the guidance, PEPFAR explicitly allowed funds to be used for needle and syringe exchange programs (NSPs) for the first time as one component of comprehensive HIV prevention programs among PWIDs [202]. The policy shift was announced following congressional lifting of the domestic ban on NSPs as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2010 in December 2009. As mentioned earlier, studies have consistently shown that NSPs—providing clean, unused syringes and a range of other services, including referrals and linkages with drug treatment, HIV testing and counseling and antiretroviral (ARV) treatment for PWIDs—result in marked decreases in drug-related risk behaviors (e.g., sharing of contaminated injection equipment, other unsafe injection practices and frequency of injections) and decrease the risk of HIV transmission. PEPFAR also supports procurement of methadone and buprenorphine and provides funds for interventions along with technical assistance to host governments and partners. The USG policy and programs are consistent with the 2009 World Health Organization, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, and UNAIDS Technical Guide for countries to set targets for universal access to HIV prevention, treatment and care for PWIDs. PEPFAR works with partner governments and civil societies to address the imbalance between the high levels of HIV risk and disease burden among PWIDs and the low level of coverage of a comprehensive package of prevention, treatment and care services. The PEPFAR policy and comprehensive HIV prevention package, including NSP, is now accepted by The Office of National Drug Control Policy for the first time, and endorsed in the 2010 National Drug Control Strategy [200, 201]. The PEPFAR 5-year strategy seeks to expand prevention, treatment and care services for PWIDs in both concentrated and generalized epidemics.

In 2009, President Obama committed additional funds through the Global Health Initiative (GHI) to support the work of PEPFAR with an additional focus on women and children through infectious diseases, nutrition, maternal and child health, and safe water programs (http://www.pepfar.gov/ghi/index.htm). GHI activities initially focused on eight countries and have now spread to include over 20 more, many of which are countries with emerging epidemics of HIV among persons who use drugs [42, 203]. Increasing impact through strategic coordination and integration, strengthening and leveraging of key multilateral organizations, global health partnerships and private sector engagement, a women, girls and gender equality-centered approach, and promoting research and innovation are four key principles underlying implementation of GHI. These principles align with the a public health approach to addressing HIV and other blood-borne and sexually transmitted infections among drug users, in terms of providing a comprehensive package of evidence-based services and coordinated participation across public and private sectors.

The New Public Health Approach

Public Health Challenges

Persons who use drugs are at increased risk for multiple, comorbid conditions, including problems associated with drug use, such as addiction and mental health issues, multiple infections such as HIV, STIs and hepatitis, overdose, and adverse social conditions such as stigma, poverty, discrimination, and incarceration. While burden of disease is high in persons who inject drugs, availability and access to needle and syringe programs, medication-assisted treatment, and antiretroviral therapy (ART) services are limited, particularly in many low- and middle-income countries. In large part, services are limited because of structural barriers (laws, policies, and regulations and other and programmatic and operational barriers) and strongly held but unfounded beliefs by many about drug users. All of these can impede the implementation of prevention, treatment, and care services.

New Public Health Response

The challenge for the public health community is to embrace the concept that harm reduction should be a core element of a public health response to HIV/AIDS where injecting drug use exists. A ‘comprehensive package of harm reduction’ has been described in this chapter as outlined by the WHO, UNODC and UNAIDS, and provides guidance to countries on the selection of evidence-based policies and interventions, including interventions for reducing HIV transmission and treatment of HIV/AIDS and associated comorbidities [204]. For these interventions to have an impact on HIV epidemics in different countries, political will and leadership are necessary across government and nongovernment sectors to align drug control policies with public health goals, in accordance with human rights principles for the prevention, treatment and care of persons who inject drugs and are at risk for or currently are living with HIV and other blood-borne and sexually transmitted diseases. More specifically, supportive policy, legal and social environments that facilitate rather than impede the implementation of appropriate models of service delivery need to be created.

Notes

- 1.

…to “enact, strengthen or enforce, as appropriate, legislation, regulations and other measures to eliminate all forms of discrimination and against and to ensure the full enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by people living with HIV/AIDS and members of vulnerable populations” [5].

- 2.

- 3.

In this article, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) include bacterial infections, syphilis, gonorrhea and Chlamydia unless otherwise noted.

- 4.

Not all drug users inject drugs, and the proportion of injecting drug users to non-injection drug users varies by the type of drug used.

- 5.

A major challenge to understanding the burden of drug use comes from the data as definitions of drug use and methods of calculation vary.

- 6.

In 2009, there were 4.4 syphilis cases, 99.1 gonorrhea cases and 409.2 Chlamydia cases per 100,000 population in the United States [64].

- 7.

For more on ATS, trafficking, and patterns of use, see World Drug Report 2010 [27].

- 8.

After the 21 years of banning the use of Federal funds for needle and syringe programs, in 2009 the law changed although some states still challenge Federal allowance of these programs. Subsequently, the Congress of the United States reinstated the ban on using federal funds to support needle exchange programs by adding restrictive language to the spending bill of 2012. The ban was reinstated despite strong evidence and the endorsement of major scientific bodies that needle exchange programs as a component of a comprehensive HIV prevention programs are highly effective in preventing the spread of HIV among persons who inject drugs. This ban impacts both domestic and global programs

- 9.

In this document, medication assisted therapy (MAT), methadone maintenance therapy (MMT), and opioid substitution therapy (OST) all define similar treatment modalities. The text reports the data according to the terms used by the study authors.

- 10.

Gostin and Lazzarini (1997) provide a fuller discussion of the theory and science and consequences of public health and criminal justice approaches [66].

- 11.

Pharmacies only in some cities.

- 12.

See IOM for a review of the evidence and discussion of the limitations of the studies.

- 13.

Methadone maintenance treatment has been available in the United States since 1964 [141].

- 14.

See the following reports for more elaborate discussion: International Harm Reduction Association. Global State of Harm reduction, 2010; Needle & Zhao, HIV Prevention among Injection Drug Users: Closing the Coverage Gap, 2010.

- 15.

The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), works in more than 80 developing countries-those with generalized and concentrated HIV epidemics. The program focuses on prevention strategies to decrease new infections, and life-saving treatment and care for those already living with HIV.

References

Wodak A, Cooney A. Effectiveness of sterile needle and syringe programming in reducing HIV/AIDS among injecting drug users. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

Needle R, Burrows D, Friedman S, et al. Effectiveness of community-based outreach in preventing HIV/AIDS among injection drug users. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

Farrell M, Marsden J, Ling W, Ali R, Gowing L. Effectiveness of drug dependence treatment in preventing HIV among injecting drug users. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

Piot P, Zewdie D, Turmen T. HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment. Lancet. 2002;360(9326):86–8.

UNGASS. Declaration of commitment on HIV/AIDS. New York: United Nations; 2001.

UNAIDS. Call for urgent action to improve coverage of HIV services for injecting drug users. UNAIDS 2010 March 10; Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/Resources/FeatureStories/archive/2010/20100309_IDU.asp.

Jurgens R, Ball A, Verster A. Interventions to reduce HIV transmission related to injecting drug use in prison. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(1):57–66.

Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, et al. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet. 2008;372(9651):1733–45.

Gordon RJ, Lowy FD. Bacterial infections in drug users. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(18):1945–54.

Hoffmann CJ, Thio CL. Clinical implications of HIV and hepatitis B co-infection in Asia and Africa. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(6):402–9.

Roy KM, Goldberg DJ, Hutchinson S, et al. Hepatitis C virus among self declared non-injecting sexual partners of injecting drug users. J Med Virol. 2004;74:62–6.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for acute viral hepatitis—United States, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(SS-2):1–24.

Urbanus AT, van de Laar TJ, Stolte IG, et al. Hepatitis C virus infections among HIV-infected men who have sex with men: an expanding epidemic. AIDS. 2009;23(12):F1–7.

Danta M, Brown D, Bhagani S, et al. Recent epidemic of acute hepatitis C virus in HIV-positive men who have sex with men linked to high-risk sexual behaviours. AIDS. 2007;21(8):983–91.

Des Jarlais C, Semaan S. HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in injection drug users and crack cocaine smokers. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit JN, Corey L, et al., editors. Sexually transmitted diseases. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. p. 237–55.

Needle R, Zhao L. HIV prevention among injection drug users: closing the coverage GAP. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies Global Health Policy Center; 2010.

Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Ali H, et al. HIV prevention, treatment, and care services for people who inject drugs: a systematic review of global, regional, and national coverage. Lancet. 2010;375(9719): 1014–28.

Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Adam P, et al. Estimating the level of HIV prevention coverage, knowledge and protective behavior among injecting drug users: what does the 2008 UNGASS reporting round tell us? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52 Suppl 2:S132–42.

Degenhardt L, Mathers B, Vickerman P, Rhodes T, Latkin C, Hickman M. Prevention of HIV infection for people who inject drugs: why individual, structural, and combination approaches are needed. Lancet. 2010;376(9737):285–301.

Gostin LO, Lazzarini Z. Prevention of HIV/AIDS among injection drug users: the theory and science of public health and criminal justice approaches to disease prevention. Emory Law J. 1997;46(2):587–696.

Jurgens R, Csete J, Amon JJ, Baral S, Beyrer C. People who use drugs, HIV, and human rights. Lancet. 2010;376(9739):475–85.

UNODC. World Drug Report. New York: United Nations; 2008.

International HIV/AIDS Alliance. Global commission on HIV and the law. International HIV/AIDS Alliance 2010. Available from: http://www.worldaidscampaign.org/en/Global-Programmes/Global-Commission-on-HIV-and-the-Law.

International HIV/AIDS Alliance, Commonwealth HIV and AIDS Action Group. Enabling legal environments for effective HIV responses: a leadership challenge for the Commonwealth. 2010.

UNAIDS. Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Beyrer C, Razak MH, Lisam K, Chen J, Lui W, Yu XF. Overland heroin trafficking routes and HIV-1 spread in south and south-east Asia. AIDS. 2000;14(1):75–83.

UNODC. World Drug Report. New York: United Nations; 2010.

Ditton J, Frischer M. Computerized projection of future heroin epidemics: a necessity for the 21st century? Subst Use Misuse. 2001;36(1–2):151–66.

Hughes PH, Rieche O. Heroin epidemics revisited. Epidemiol Rev. 1995;17(1):66–73.