Abstract

In family research, the topic of remarriage and stepfamilies has been of interest to scholars since the landmark study by Jessie Bernard in 1956. In fact, the Journal of Marriage and Family decade reviews began addressing remarriage and stepfamilies in 1980 when these topics were included as a “nontraditional family form” (Macklin, 1980, citing 29 studies from 1970s) and as a “noninstitution” (Price Bonham & Balswick, 1980, citing an additional 17 studies). By 1990 when Coleman and Ganong reviewed studies of remarriage and stepfamilies from the 1980s, they noted that the literature had grown to “well over 200 published empirical works” (p. 925). They also noted that (a) stepchildren were the focus of much of the research rather than remarriage and marital functioning in stepfamilies and (b) studies typically assumed a problem-oriented or deficit-comparison approach. This approach addressed between group comparisons of those in first-marriage families with those in stepfamilies with limited attention to stepfamily strengths and processes.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

In family research, the topic of remarriage and stepfamilies has been of interest to scholars since the landmark study by Jessie Bernard in 1956. In fact, the Journal of Marriage and Family decade reviews began addressing remarriage and stepfamilies in 1980 when these topics were included as a “nontraditional family form” (Macklin, 1980, citing 29 studies from 1970s) and as a “noninstitution” (Price Bonham & Balswick, 1980, citing an additional 17 studies). By 1990 when Coleman and Ganong reviewed studies of remarriage and stepfamilies from the 1980s, they noted that the literature had grown to “well over 200 published empirical works” (p. 925). They also noted that (a) stepchildren were the focus of much of the research rather than remarriage and marital functioning in stepfamilies and (b) studies typically assumed a problem-oriented or deficit-comparison approach. This approach addressed between group comparisons of those in first-marriage families with those in stepfamilies with limited attention to stepfamily strengths and processes.

The following decade saw research on remarriage and stepfamilies burgeon, and Coleman, Ganong, and Fine (2000) reviewed over 850 published works for the decade review at the onset of the twenty-first century. Children remained a primary focus of much of the research (over 200 studies). However, there was more attention given to marital and family processes with a growing interest in the broader social context in which such families were embedded. Some attention to how studies and findings had changed over time and diversity in stepfamilies, including cohabiting, and gay and lesbian stepfamilies, also was witnessed. Since 2000, scholars have continued studying remarriage and stepfamilies with over 500 published research articles and some particularly noteworthy edited volumes (e.g., Pryor, 2008a), which were reviewed for inclusion in this chapter. The words “remarriage,” “stepfamily,” and “stepparent” are used to identify published works for review here.

Changes in family formation today require scholars interested in remarriage and stepfamilies to be more inclusive and look beyond simply those unions created following divorce or death of a spouse. Such inclusiveness means that we must also attend to couples who never marry but form committed partnerships which later dissolve. These individuals go onto repartner through marriage or cohabitation. As such, we use repartner and repartnership as broader concepts referring to those who remarry, as well as those who form nonlegal second or higher order unions, including those with or without children present. Accordingly, we support the recommendation of Teachman and Tedrow (2008) and adopt an inclusive definition of stepfamilies that also includes (a) those that form as a result of nonmarital repartnering rather than only from divorce or death of spouse and (b) those that are same-sexed partnerships. Such inclusiveness reflects much of public opinion (Weigel, 2008) and the realities of family life for children and adults today (Dunn, O’Connor, & Levy, 2002). In this chapter we provide a comprehensive synthesis and critique of the extant literature on remarriage and stepfamilies from this inclusive perspective, and we examine the theory and methods used in these studies.

Prevalence and Demography of Remarriage and Stepfamilies

Scholars generally agree that conceptualizing family is a daunting task, and there is a good deal of debate about what constitutes a family (see Chap. 3; Weigel, 2008). This task is further complicated by the increasing separation of family and household as concepts (see Cherlin, 2010). The U.S. Census (2010) defines a household as including all individuals living in one housing unit. Households are further delineated as family and nonfamily; a family household includes residents that are related by biological or legal means, such as birth, marriage, or adoption. Using this definition, a stepfamily includes a married couple living together with at least one stepchild (i.e., a child not biologically connected to one of the spouses). The obvious drawback of this definition is that it excludes stepfamilies in which a stepchild was adopted by a stepparent (these are rare occurring cases) or those with a nonresident stepchild. Additionally, couples who are partnered but not legally married and where one of the partners also has a child from a different partnership or marriage are excluded. Here, we label these repartnered families as nonlegal stepfamilies. Because “child” refers to persons 17 years or younger residing in the household, more exclusions include those stepfamilies whose stepchildren are older and or reside elsewhere.

Such complexity of family formation makes the way in which remarriages and stepfamilies are conceptualized and studied more challenging. However, even when definitions are clearly articulated, accurate estimates of their prevalence remain elusive. Decisions to discontinue the collection of certain information which previously had allowed us to develop more rich demographic profiles (see Bramlett & Mosher, 2002) and the initiation of other data collections which will permit greater accuracy in the future (Kreider & Elliott, 2009) complicate any contemporary estimates.

Estimates of Prevalence

Recent evidence (Kreider, 2005) shows that, in 2001, 30.2 % of all marriages were a remarriage for at least one of the partners; this is down from earlier estimates that 45 % were remarriages—likely a shift related to increased cohabitation rates (Cherlin, 2010; Sweeney, 2010). Further, Kreider (2005) noted that of the 30 % about 17 % were remarriages of only one of the partners, and 13 % were a remarriage for both. Our best estimates suggest that about 65 % of remarriages form stepfamilies with either stepfather-only or stepfather–stepmother families being the most common; stepmother-only families are the least common. Other data using an urban cohort showed that almost 60 % of unmarried couples had at least one child from a prior union, constituting nonlegal stepfamilies (Carlson & Furstenberg, 2006).

Other estimates from the 2004 Survey of Income and Program Participation (Kreider, 2007) show that of the 69.7 % of children living with two parents (3 % are living with unmarried parents) about 7.6 % included a stepparent, and the majority were resident stepfathers. Another 26 % lived with one parent of which 8.3 % lived with a mother and her partner, 1.9 % with a father and his partner, and 0.9 % with a single stepparent. Another estimate from these data shows that about 16.6 % of all children live in households where there is a stepparent, stepsibling, or halfsibling. Of these, 65.9 % have only a halfsibling, 8 % have only stepsiblings, and 2.4 % have both. Lastly, just under 40 % of cohabiting couples have a child living with them, although it is often unknown whether that child is the biological child of only one adult present in the household or of both adults. Given the higher probability of a child experiencing the dissolution of their parent’s cohabiting union (Cherlin, 2010), it is likely that many of these families would be considered repartnered nonlegal stepfamilies, thereby increasing the prevalence of stepfamilies in the USA.

Remarriages tend to end slightly more frequently than first marriages, a consistent finding over time (Coleman & Ganong, 1990; Coleman et al., 2000). However, Kreider (2005) reported that it takes about the same amount of time for first marriages and remarriages to dissolve with the current median of about 8 years, up from earlier estimates of 4.5 years. Also, the findings regarding the risk of postdivorce cohabiting unions dissolving are mixed, with some suggesting that it is higher than the likelihood of a remarriage ending in redivorce while others concluding that this is not the case (Cherlin, 2010).

Demographic Characteristics

Studies of individuals who remarry or form stepfamilies show that they are more likely to be White and less likely to be employed than those in first-marriage families (Sweeney, 2002). Others show that most of those who remarry cohabited prior to doing so (Xu, Hudspeth, & Bartokowski, 2006). Nonlegal stepfamilies are more likely to be Black, have lower incomes, and often have children from prior partnerships (Kreider, 2007).

Other evidence focusing on women shows that those who are younger, more educated (especially those with postbaccalaureate degrees), and had three or more children are less likely to remarry (Sweeney, 2002). Of women who do remarry, Wolfinger (2007) found that their remarriages averaged 10 years, the average time between marriage and remarriage was 5 years, most were White and had children from their first marriage, and 32 % experienced a second divorce. These findings are similar to those reported earlier by Wu and Schimmele (2005) using data from the 1995 General Social Survey. Clearly, for women, it appears that education and presence of children from a first marriage are key factors affecting future remarriage.

Alternatively, for men having more education (even postbaccalaureate degrees), children from a prior marriage, and being more religious is associated with an increased likelihood of remarriage (Brown, Lee, & Bulanda, 2006; Goldscheider & Sassler, 2006). Also, London and Elman (2001) found that compared to Whites, Black men are more likely to marry divorced women in general, especially those with children. However, longer first marriages generally were linked to a lower likelihood of nonmarital repartnering (Wu & Schimmele, 2005).

Children and Union Formation

The presence and influence of children on repartnering in any form in general has received considerable attention. In fact, Teachman and Tedrow (2008) concluded that the most significant shift in the last decade was a significant increase in the number of households with at least one stepchild present; most commonly these were stepfather households. They further contend that this shift means an increase in the likelihood that children will spend at least some time in a stepfamily before reaching early adulthood, especially when those born into a nonmarital union are included.

As noted, children from a prior marriage or union reduce the likelihood for women of remarriage, but increase the likelihood for men (e.g., Brown et al., 2006). However, other findings (Lampard & Peggs, 1999) showed that the likelihood of repartnering via remarriage or cohabitation decreased as the number of children from a first marriage increased for both men and women, so there may be a point at which too many children negatively affect one’s willingness to repartner. There is also evidence that women with resident children tend to marry men with children, thereby forming complex stepfamilies (Goldscheider & Sassler, 2006); however, single men are more willing to marry a divorced woman without children (Goldscheider, Kaufman, & Sassler, 2009), and men with nonresident children are more likely to cohabit rather than to marry or remarry (Stewart, Manning, & Smock, 2003).

Adults and Remarriage or Repartnering

Compared to research examining the influence of family structure and processes on children in stepfamilies, less is known about the relationship dynamics and adult outcomes of those who recouple (Sweeney, 2010; van Eeden-Moorefield & Pasley, 2008). Here, we review the research on relationship transitions and adjustment, relationship quality, relationship stability, and adult outcomes for those who repartner whether through remarriage or cohabitation. The term remarriage is used only for studies that specifically delimited their samples to those entering a second or higher-order (e.g., third, fourth) marriage.

Transitioning to Remarriage and Adjustment

Research on the transition to remarriage has received less attention than other areas in the extant literature (see Coleman & Ganong, 1990; Coleman et al., 2000; Pasley & Moorefield, 2004; Sweeney, 2010). The majority of studies that address transitions also lack attention to stepfamily complexity or the diverse pathways by which repartnerships are formed. Although we know that couples entering a remarriage do so with a belief that it will operate like a first marriage and that this belief is linked to more adjustment difficulties (Bray & Kelly, 1998), we know less about how couples create satisfying and successful repartnerships, including remarriages (Coleman et al., 2000; Sweeney, 2010). A common pathway to remarriage is cohabitation (Montgomery, Anderson, Hetherington, & Clingempeel, 1992), often with multiple partners over time, and doing so delays remarriage (Xu et al., 2006). In fact, some report that cohabitation is the preferred repartnership structure for men (Stewart et al., 2003). Although less common, a study of widowed individuals, using data from the American Changing Lives Survey, found that men who received more social support following the death of a spouse also reported more interest in dating and remarriage within the first 18 months than did women (Carr, 2004). For women, being younger and less happy was linked to interest in remarriage, whereas more depression, less financial security, and being older reduced such interest.

Once a repartnership is formed, remarried couples report less cohesion compared with those in first marriages, although the difference is not clinically deficient (e.g., Bray, 1998). Other evidence shows that remarried women want and have more shared power than their first-married counterparts (Crosbie Burnett & Giles Sims, 1991; Ganong, Coleman, & Hans, 2006; Pyke & Coltrane, 1996), and this is evident of financial decisions as well (Burgoyne & Morrison, 1997; Pasley, Sandras, & Edmondson, 1994; Vogler, 2005). Specific to stepfamilies, partners who are parents in these families reported having more say in decision making, including financial decisions (Moore, 2008). Interestingly, how increased power affects other marital interactions is less well understood, especially from the husband’s point of view.

Regarding other relationship processes, couples who report high levels of adjustment also report lower levels of negative affect (DeLongis, Capreol, Holtzman, O’Brien, & Campbell, 2004). Some research (Halford, Nicholson, & Sanders, 2007) suggests that those in stepfamilies demonstrate less negativity during marital conflict and are more likely to withdraw from conflict than are first marrieds—behaviors that may facilitate consensus building and adjustment (e.g., Bray, Berger, & Boethel, 1994; Ganong & Coleman, 1994). This supports earlier findings (Hobart, 1991) that men concede more during conflict discussions, which also could be perceived as a withdrawal strategy. Other research (Bray & Kelly, 1998) found that remarried couples reported more open expressions of anger, irritation, and criticism during conflict discussions. Yet, any negative effects of these on adjustment were buffered by other supportive behaviors from a spouse.

Relationship Quality

Early studies of relationship quality found few differences between those in remarriage compared with those in first marriages based on sex, stepparent status, or stepfamily complexity (see Vemer, Coleman, Ganong, & Cooper, 1989); differences that did exist had small effect sizes, meaning that the strength of the relationship between the variables was significant but small and of little practical significance. Others (e.g., Guisinger, Cowan, & Schuldberg, 1989) argued that relationship quality in remarriages, particularly relationship satisfaction, was similar to that of first marriages, with declines experienced in the earlier years before stabilizing somewhat. More contemporary research (Kurdek, 1999) suggests that the presence of children in first marriages is related to sharper declines in satisfaction than in remarriages. Other research (Hobart, 1991) found poorer quality among complex stepfamilies and among stepfather but not stepmother families (Kurdek, 1991). Still others (e.g., Brown & Booth, 1996) reported poorer relationship quality among remarrieds compared with first marrieds, so the overall findings by the end of the 1990s were contradictory.

Few studies were published in the last decade that cleared up these contradictions. In fact, few studies examined predictors of relationship quality or how quality differs within groups, despite scholars suggesting that differences likely exist (Coleman et al., 2000; Rogers, 1996). These few studies found that satisfaction in remarriage does not differ between rural and urban couples, although feeling financially constrained or concerned over finances predicted lower satisfaction among the rural remarried couples (Higginbotham & Felix, 2009). Another study (Beaudry, Boisvert, Simard, Parent, & Blais, 2004) found that poorer spousal communication skills, lower income, and having older children were linked to lower marital satisfaction.

Relationship Stability

The stability of remarriages is slightly less than that of first marriages, with about 50–60 % of remarriages ending in divorce (Bumpass, Sweet, & Martin, 1990; Kreider & Fields, 2002). There is also some evidence that dissolution among those in cohabiting unions following divorce is common (Pevalin & Ermisch, 2004; Xu et al., 2006). When children from a prior union are present, the dissolution rates are higher, likely due to the increased potential for conflict surrounding stepchildren and former spouses—topics noted as issues in previous research (Bray, 1998; Coleman et al., 2000). In fact, Booth and Edwards (1992) suggested that stability is lower in remarriages due to being “poor marriage material,” lack of homogamy produced by the smaller marriage market, and lack of role clarity and support. Demographers show that instability is associated with race (Blacks more likely; Hispanics least likely), younger age at remarriage (less than 25), not growing up with two parents, the presence of children from prior unions, and lower income (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002). Unfortunately, few recent studies examined stability in spite of calls to do so (Ganong & Coleman, 2004), and to do so in such a way that reflects the true complexity of these families (Adler-Baeder & Higginbotham, 2004).

We know that relationship processes, quality, and stability are linked. For example, scholars found that marital conflict (a relationship process) influences relationship quality in remarriage (Beaudry et al., 2004; Bodenmann, Pihet, & Kayser, 2006), and that decreases in marital quality are linked with decreases in stability (Stewart, 2005; White & Booth, 1985). A recent study assessed these multiple links over time, using all three waves from the National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH; van Eeden-Moorefield & Pasley, 2008). These investigators found that higher marital conflict and lower perceived fairness at Time 1 was related to decreases in marital quality at Time 2 and higher instability, including redivorce, at Time 3. Further, these relationships were influenced by family complexity. Specifically, fairness predicted marital quality only for couples in stepfamilies and accounted for 42 % of the variance in stability compared to 29 % for those in remarriages without children. We believe that more research is needed about such processes and their linkages, because little research addresses these connections in general or differentiates them within various types of repartnerships.

Adult Outcomes

Historically, studies examining the effects of remarriage on adults most commonly addressed indicators of well-being (Spanier & Furstenberg, 1982), life satisfaction (Weingarten, 1985), health and substance use (Mitchell, 1983). These studies typically used a deficit approach (i.e., comparing those in remarriages to those in first marriages), and generally found few or no differences (e.g., Coleman et al., 2000; Richards, Hardy, & Wadsworth, 1997). However, some studies (e.g., Neff & Schlutter, 1993) found higher distress among remarrieds, whereas others found improved outcomes (Mitchell, 1983; Spanier & Furstenberg, 1982). The consensus among many early scholars was that (a) a selection effect might explain the mixed findings, and (b) individual characteristics and relationship processes likely are more important than marital status alone (e.g., Booth & Amato, 1991; Coleman et al., 2000).

More recent studies of adult outcomes have used longitudinal data, and their findings remain fairly consistent with previous results. For example, Pevalin and Ermisch (2004) found that poor mental health increases the likelihood of dissolving a first marriage, a cohabiting relationship, or a repartnership (cohabiting union following a divorce or dissolution of a second cohabiting union), and this risk holds for men and women. A recent study by O’Connor, Cheng, Dunn, Golding, and The ALSPAC Study Team (2005) found that women who were separated following a remarriage are more depressed than those who were separated after a first marriage, but their depression dissipated over time.

Overall, this research suggests that adults fair similarly in first marriages and remarriages but what remains to be determined is the nature of any within-group variations. Adoption of a normative–adaptive approach, comparing types of remarriages, nonlegal repartnerships, and both legal and nonlegal stepfamilies would provide useful information for understanding some of the conditions that affect adults.

Living in a Stepfamily

Commonly used in studies of stepfamilies, family systems theory suggests that all persons within the family are interconnected and reciprocally influential, and these connections have received increased attention by scholars. Because much literature suggests that the nature of the stepparent and stepchild relationship is a strong predictor of the stability and quality of the spousal relationship (e.g., Coleman et al., 2000), studies of stepfamily life often focus on stepparents.

Stepparenting

Compared to parenting a biological child, it is well documented that stepparenting is more difficult (e.g., MacDonald & DeMaris, 1996; Pasley & Moorefield, 2004). This difficulty often results from variations in role expectations and behaviors leading to role confusion, boundary ambiguity, and conflict, especially for new stepparents (Bray & Kelly, 1998; Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). There is evidence that role clarity and role agreement are related to positive adjustments in stepfamilies (Coleman et al., 2000). Further, when any member, dyad, or even triad experience adjustment difficulties, these difficulties also negatively influence other individuals within the family (Gosselin & David, 2007), including those external to the immediate household. Thus, understanding step- and coparenting is key to understanding stepfamily life. Unfortunately, we know more about coparenting following divorce than coparenting after at least one of the previous spouses repartners—an area deserving more attention in the future. Where appropriate we have included some of the few studies focusing on coparenting processes in the sections below.

Scholars recommend that successful stepparenting includes adopting parenting behaviors slowly and in ways less forcefully than traditional parenting, particularly around discipline and limit setting (e.g., Bray & Kelly, 1998; Fisher, Leve, O’Leary, & Leve, 2003; Hetherington & Kelly, 2002; Mason, Harrison-Jay, Svare, & Wolfinger, 2002). Other scholars add that stepparents should provide support and warmth to the stepchild (Mason et al.), allowing the stepparenting relationship to develop gradually over time. It is frequently recommended that time is required for this adjustment (e.g., Hetherington & Kelly, 2002; Marsiglio, 2004), so we speculate that when a stepparent slowly adopts a parenting role, the coparenting relationship between former spouses is less strained, thereby reducing potential for stepparent–former spouse conflict.

Research has examined a number of factors affecting stepparenting. For example, sex-matched stepparents and stepchildren (e.g., stepfathers and stepsons; Schmeeckle, 2007) and coresidence (Schmeeckle, Giarrusso, Feng, & Bengtson, 2006) aid in stepparenting. For stepparents, time is associated with decreases in depressed mood and increases in life satisfaction (Ceballo, Lansford, Abbey, & Stewart, 2004). Ambiguity in the stepparenting role (Gosselin & David, 2007), becoming more disengaged as a stepparent over time (Fisher et al., 2003), but not initially, have the opposite effect. The birth of a common child to a stepfamily is associated with less involvement by the stepparent with the stepchild (Stewart, 2005). Still other research shows that married stepfamilies exhibit higher quality parenting behaviors compared with their cohabiting counterparts (Berger, Carlson, Bzostek, & Osborne, 2008). Experiences with stepparenting also vary by age of child, and we address these findings throughout the following sections. Generally, stepfamily adjustment and stepparenting is more positive when stepchildren are younger and most negative when stepchildren are adolescents.

Lastly, stepfathers and stepmothers share many common experiences, although there are some differences, of which some are associated with residential status, and we address these below. To date, however, much less is known about the experience of stepmothers than stepfathers (e.g., Sweeney, 2010).

Stepfathering

Stepfathers have sustained scholarly interest over time, and much of the focus in the past decade is on stepfather–stepchild interactions, including quality of their parenting and involvement. Some research (e.g., Hetherington & Kelly, 2002) shows that stepfathers are given greater latitude in parenting (e.g., expectations for less responsibility in daily care and monitoring than stepmothers) and that his early disengagement is associated with more tension in the mother–child relationship (DeLongis & Preece, 2002). Other research suggests that the quality of stepfather involvement does not differ from that of a biological father (Adamsons, O’Brien, & Pasley, 2007), although stepfathers are noted to provide less monitoring (Fisher et al., 2003) and better control of their negative feelings (Bray & Kelly, 1998). There is also some research suggesting that the quality of the remarriage (Adamsons et al., 2007) and the stepfathers’ perceptions of stepchild adjustment (Flouri, Buchanan, & Bream, 2002) affect his involvement in expected ways.

Early research showed that stepfather–stepdaughter involvement is more avoidant and can quickly become hostile (Vuchinich, Hetherington, Vuchinich, & Clingempeel, 1991), and this is consistent with more recent findings. For example, studies show that the stepfather–stepchild relationship is moderated by duration of the remarriage (longer marriage = better relationship), and age and sex of the child (easier with stepsons) (e.g., Bray & Kelly, 1998; Falci, 2006; Golish & Caughlin, 2002). Other findings show that compared with father–daughter dyads stepfather–stepdaughter dyads are less close over time (Falci, 2006).

Some studies explored stepfathering from the child’s perspective. Their results suggest that when the quality of their relationship is perceived by the child to be lower, there is less involvement overall, and involvement is of poorer quality (e.g., Cooksey & Fondell, 1996; Lansford, Ceballo, Abbey, & Stewart, 2001; MacDonald & DeMaris, 2002). Also, stepchildren believe that stepfather involvement should be minor and secondary to that of the mother (Moore & Cartwright, 2005). Retrospective interviews with adult children, who were first studied 20 years earlier when their parents divorced (Ahrons, 2007), show that those whose parents remarried quickly described the quality of the stepfather–stepchild relationship as more tenuous early on and stabilizing over time. In another study, when young adult men are asked about their stepfathers, they report higher nurturance and involvement by adoptive compared with nonadoptive stepfathers (Schwartz & Finley, 2006).

A new area of investigation related to stepfathers has focused on relationships with the biological father. These few qualitative studies demonstrate the importance of alliance building for enhancing both the involvement and quality of stepfathering (Marsiglio, 2004; Marsiglio & Hinojosa, 2007). We believe these studies provide valuable information from which future studies can explore the father–stepfather coparental relationship and stepfamily and child adjustment.

Another newer area of research examined the differences in parenting quality and cooperation between married and cohabiting fathers and married and cohabiting stepfathers. Using data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, Berger et al. (2008) found that parenting quality was higher among married fathers and stepfathers compared with cohabiting fathers and stepfathers. Findings also showed that although all stepfathers were perceived as less trustworthy, they were engaged in cooperative parenting more than were fathers. Such studies provide valuable insight into understanding stepfamilies and stepfathering in the new millennium, emphasizing within-group variation.

Stepmothering

Because the majority of nonresident parents are biological fathers, the majority of nonresident stepparents are stepmothers (Stewart, 2001). These women have received more attention than have resident stepmothers (Sweeney, 2010), although research on both groups is quite limited (e.g., Henry & McCue, 2009) and deserving of increased attention. Earlier research suggested the potential for conflict and other negative interactions is greater with resident stepmothers compared with nonresident stepmothers (e.g., MacDonald & DeMaris, 1996), and this may be a reflection of the gendered nature of daily family life, including stepfamily life (Dunn, Davies, O’Connor, & Sturgess, 2000). Other research on resident stepmothers suggests a diversity of roles that are not clearly understood by family members, although these stepmothers report difficulty establishing positive roles due to the wicked stepmother stereotype (Sweeney, 2010).

More contemporary research on nonresident stepmothers (Weaver & Coleman, 2005) identified three themes in their interviews with 11 stepmothers about their roles. These stepmothers saw their role as (a) an adult friend in which they were mentors and provided emotional support to stepchildren; (b) supporters of the father–child relationship and acting as a liaison between the father and mother—a role others have found to be linked to increased conflict, especially when the father was reluctant to intervene in parenting-related conflicts (Henry & McCue, 2009); and (c) an outsider, where they were invisible parents during father–child interactions. Other research on nonresident stepmothers shows that they report higher levels of depressed mood, anxiety, and stress often related to perceptions about their inability to take an active role in stepfamily functioning, especially in terms of parenting, financial matters, legal issues (Henry & McCue, 2009) and division of household labor (Johnson et al., 2008). Taken together, this research suggests that when nonresident stepmothers and their families are able to negotiate a balance between being an invisible stepparent and an entirely engaged parent, family and individual adjustment might be improved; however, no studies have examined this.

Residential Status, Step/Parenting, and Coparenting Dynamics

Changes in the legal context have resulted in more joint custody (sometimes referred to as shared parenting) and regular coparenting involvement of nonresident parents after divorce (Gately, Pike, & Murphy, 2006). Although coparental conflict can serve as a barrier to nonresident parent involvement (Stewart, 1999), there is mounting evidence of the value of continuing involvement by nonresident parents for child development (Jackson, Choi, & Franke, 2009). Much of the recent research on nonresident parenting used data from the NSFH, did not differentiate findings by sex of nonresident parent. The focus of this research was on issues pertaining to the nature (frequency, e.g., Aquilino, 2006) and quality of contact (e.g., White & Gilbreth, 2001) with the nonresident parent and child outcomes (e.g., Gunnoe & Hetherington, 2004).

Generally, scholars suggest that nonresident parents should not be “replaced” by stepparents or cut off from being involved in the child’s life (e.g., Clapp, 2000). Thus, the continued contact and involvement by both parents is important. Research indicates that nonresident mothers tend to have more contact and involvement with their children compared to nonresident fathers (Gunnoe & Hetherington, 2004; Stewart, 1999). Factors that are known to decrease involvement by nonresident parents include parental remarriage (Amato, Meyers, & Emery, 2009; Stewart, 1999) or repartnering (Stewart, 1999) as well as the increased age of children (Amato et al., 2009), an effect that may reverse as children make the transition to young adulthood (Aquilino, 2006). Other factors that decrease nonresident parent involvement include negativity in the coparental relationship, lower educational attainment by parents, poor parental employment (Jackson et al., 2009), failure to pay child support, and the birth of a child outside of marriage (Amato et al., 2009).

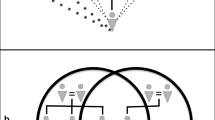

Because our interest is primarily on the relationship between nonresident parents and stepparents, we note that several models exist that explain how nonresident parent–child relationship quality affects child outcomes within the context of stepfamilies. Specifically, White and Gilbreth (2001) offered three explanations: (a) the accumulation model suggests that having a nonresident father and resident stepfather results in improved child outcomes because of the added resources brought by two fathers, (b) the substitution model asserts that the stepfather becomes the de facto father figure by replacing the biological father, and (c) the loss model suggests that stepfathers do not perform all of the functions of a biological father, and therefore, the child loses an important functional relationship when the biological father lives elsewhere. King (2006) refined and extended these models to include the following: (a) the additive model similar to the accumulation model; (b) the redundancy model suggests that as long as the child is close to one father, their well-being will not be affected and that the addition of a second father is unnecessary; (c) the primacy of biology model suggests that closeness to the biological nonresident father is most important in predicting positive child outcomes; conversely (d) the primacy of residency model suggests that residency is most important; and (e) the irrelevance model suggests that the relationship with a biological mother is most important to child outcomes above any relationship with a father. We agree with Pryor (2008b) who concluded that research findings provide the most support for the additive and accumulation models suggesting that both father and stepfather affect child outcomes. Unfortunately, none of these models have been adequately tested.

The Effects on Children

The myriad difficulties associated with union, household, and life transitions accompanying a parent’s repartnership have some negative effects on children (e.g., academic, behavioral, and emotional). Several comprehensive reviews (e.g., Coleman & Ganong, 1990; Coleman et al., 2000; Pasley & Moorefield, 2004; Sweeney, 2010) over the past decades and two meta-analyses (Amato, 1994; Jeynes, 2006) have documented these effects well, with most attention given to children with remarried parents specifically. Much of this research also takes a deficit perspective and uses between-group designs (Coleman & Ganong, 1990; Coleman et al., 2000) and has provided little insight into within-group differences. Over the past 20 years increasingly studies have relied on longitudinal data, thereby lending confidence to the findings.

In general, results from studies suggest that children living in a stepfamily fare worse than children living in an intact family and similar to those living in single-parent households. These differences tend to be small (Amato, 1994; Jeynes, 2006), and many dissipate over time particularly when a remarriage occurs earlier in a child’s life (e.g., Zill, Morrison, & Coiro, 1993). Overall, scholars conclude that most children do well (Coleman et al., 2000), with the recognition that some findings have been mixed or vary in strength, especially when demographic controls are not used (e.g., Hoffman, 2002; Jeynes, 2006). Research using a normative–adaptive perspective focuses on within-group designs (Coleman & Ganong, 1990), and this approach has been used recently to identify family processes that support or hinder child development (e.g., Dunn, 2004).

In this section, we address common findings in the research as well as unique findings from recent studies. We focus on children’s academic outcomes, behavior problems (internalizing, externalizing, conduct problems), and substance use. A strength of many of the recent studies is their use of longitudinal data.

Academic Outcomes

Consistent with previous reviews (e.g., Coleman & Ganong, 1990; Coleman et al., 2000; Pasley & Moorefield, 2004) and compared with children from intact families, children living in stepfamilies, on average, fare worse. In contrast, children from stepfamilies fare slightly better in some indicators of academic outcomes (e.g., school engagement; Teachman, 2008) compared with those in single-parent homes (cf. Jeynes, 2006). As noted, the effect sizes are smallest for academic outcomes (Amato, 1994), but the effects last longer (Cavanagh, Schiller, & Riegle-Crumb, 2006) and are stronger when children experience more transitions (Halpern-Meekin & Tach, 2008; Hanson & McLanahan, 1996; Jeynes, 2006). Transitions that occurred more recently had less effect on academic outcomes than those occurring in the more distant past (Tillman, 2008). Importantly, recent research that produced such findings typically used longitudinal data (e.g., Heard, 2007) and examined the role of stepfamily complexity and diversity in ways that promote greater confidence in the findings (Foster & Kalil, 2007; Tillman, 2007).

A variety of indicators of academic outcomes have been included in these studies (e.g., grades, school completion, achievement test scores; Coleman et al., 2000) and continue to be used. For example, compared with children from intact families, Ham (2004) found that those in single-parent homes had GPAs 17.6 % lower, and for those in stepfamilies GPAs were 19.2 % lower. Adolescent males in stepfamilies had higher GPAs, but the reverse was true for adolescent females. Within stepfamilies, having a half- or stepsibling (Halpern-Meekin & Tach, 2008; Tillman, 2008) or being from a cohabiting stepfamily (Heard, 2007) was related to lower GPAs, especially for stepfather cohabiting stepfamilies (Tillman, 2008). Further, having half- or stepsiblings also was related to a decreased likelihood of graduating high school, obtaining higher education (Ginther & Pollak, 2004), and overall lower academic performance (Tillman, 2008). Other research (Heard, 2007) shows that those in a cohabiting stepfamily are 12 % more likely to be suspended, expelled, and score lower on math, reading, and general knowledge tests (Artis, 2007). Whereas most studies control for variables such as race and ethnicity (e.g., Heard, 2007) rather than study their effects, Foster and Kalil (2007) examined the role of race and ethnicity in relation to family structure and literacy. They found a weak relationship between family structure and literacy, except for Latino children from stepfamilies who outscored children from single-parent families.

Problem Behaviors

Internalizing

Coleman et al. (2000) concluded from the studies published in the 1990s that stepchildren experience more internalizing problems than do children in intact families, although the results by sex of child are mixed. Once again, these effects are generally small to moderate (Amato, 1994). Newer research continues to report mixed findings. For example, results from a recent meta-analysis of 61 studies (Jeynes, 2006) suggest that stepchildren experience more internalizing behavior compared with children in intact and single-parent families. Other studies (e.g., Cavanagh et al., 2006; Saint-Jacques et al., 2006; Willetts & Maroules, 2004) did not find a direct effect of family structure on internalizing behaviors using both cross-sectional and longitudinal data. Instead, the number of transitions that children experience and other factors were more predictive of internalizing. For example, Saint-Jacques et al. (2006) found that internalizing was higher among children in a higher-order stepfamily compared with children in a first step-, intact, or single-parent family. Others (Foster & Kalil, 2007) found that family structure negatively influences internalizing only for Blacks, but these effects disappear when controls are added. Still others (Breivik & Olweus, 2006) reported higher internalizing behaviors among children in step- and single-parent families compared with children in intact families, especially when the family is a stepfather family (Sweeney, 2007). Overall, these studies suggest that there are several factors affecting the link between family structure and child internalizing behaviors, especially the number of transitions, race, and type of stepfamily; some studies also show that positive stepparenting can buffer these effects (e.g., Rodgers & Rose, 2002; Willetts & Maroules, 2004).

Externalizing

Regarding externalizing behavior problems, previous research suggests slightly more consistent findings, with children living in stepfamilies exhibiting higher levels (Coleman et al., 2000), though some mixed results also are evident. Recent research on family processes shows that positive stepparenting buffers the effects on externalizing behavior similar to the buffering of internalizing behaviors (e.g., Rodgers & Rose, 2002; Willetts & Maroules, 2004). Results from a cross-sectional study (Attar-Schwartz, Tan, Buchanan, Flouri, & Griggs, 2009) indicated that conduct-related behaviors and difficulties with peers are also higher for children from step- and single-parent families than those from intact families. Other research shows that these findings are most pronounced in single-father families compared to step- and single-mother families (Breivik & Olweus, 2006). Yet, other scholars report no differences in externalizing behaviors of children by family structure (Willetts & Maroules, 2004) or differences only among higher-order stepfamilies (Saint-Jacques et al., 2006). Findings from longitudinal studies indicate that externalizing behaviors are lower than in previous decades (see Collishaw, Goodman, Pickles, & Maughan, 2007), but children in stepmother families and those in which half- and stepsiblings are present are most at-risk for these problems (Hoffman, 2006). Although there has been less attention in recent research on sex of child, some research suggests that, after controlling for parenting and maternal depressed mood, aggressive behavior is 2.5 times higher among girls than boys in stepfamilies and than those in single-parent families regardless of sex.

Substance Use and Health

Although some attention was paid to the substance use of children in stepfamilies in the past (Coleman et al., 2000), the topic gathered more attention recently with some attention also paid to health outcomes in these children. Studies using composite measures of substance use found that, compared to children in intact families, those in stepfamilies (Hoffman, 2002) and single-parent families report more use (Barrett & Turner, 2006). When examining individual drugs, a more mixed picture emerges. Specific to tobacco use, Griesbach, Amos, and Currie (2003) reported that living in a stepfamily was related to adolescent smoking even after controlling for socioeconomic status (SES), parental smoking habits, disposable income, and presence of a stepfather (Bjarnason et al., 2003); such findings were not confirmed in longitudinal analyses (Menning, 2006). Compared with those in intact families, children in stepfamilies also are 1.5 times more likely to use marijuana, but not more likely to use alcohol (Longest & Shanahan, 2007). Compared to children in single-parent families, other studies found a significantly higher rate of alcohol use in children from stepfamilies (Bjarnason et al., 2003).

Regarding global health, after controlling for education and SES, the health of stepchildren appears comparable to children in intact families (Heard, Gorman, & Kapinus, 2008). In some cases, there is evidence that stepfamilies may be more protective of children’s health compared to intact families (Wen, 2008).

Sibling Interactions

Although not the focus of much past research (Coleman & Ganong, 1990; Coleman et al., 2000), several recent studies examined sibling relationships within stepfamilies. However, this remains and understudied area. Consistent with previous decades (Baham, Weimer, Braver, & Fabricius, 2008; Coleman et al., 2000), research focused on parental treatment of siblings in complex stepfamilies and on children’s perceptions of being part of a stepfamily. Findings from both qualitative (Wallerstein & Lewis, 2007) and longitudinal quantitative studies (Jenkins, Simpson, Dunn, Rasbash, & O’Connor, 2005) indicated that stepparents argued more about and responded less to stepchildren than biological children. Also, differential treatment related to arguments was more pronounced in stepfather families, whereas stepmothers were less engaged with stepchildren overall. Contrary findings exist, as Deater-Deckard, Dunn, and Lussier (2002) reported no differences in the amount of sibling conflict between those in intact and stepfamilies, although the level of conflict was slightly higher among biological siblings than stepsiblings. Regardless of type of sibling, higher sibling conflict and perceiving differential treatment by parents was related to more internalizing problems (Yuan, 2009). Other findings indicate that siblings in stepfamilies experience decreased academic achievement (Ginther & Pollak, 2004; Tillman, 2008), and that these negative effects decreased over time (Tillman).

When asked about their families, children with stepsiblings were more likely to exclude them as family regardless of their residency (Roe, Bridges, Dunn, & O’Connor, 2006); such exclusion was related to a decreased sense of family belonging (Leake, 2007). In another study that followed children of divorce over 20 years, Ahrons (2007) found that age and frequency of contact was related to feelings of exclusion by stepchildren, but these feelings were less dramatic when a halfsibling was present. Interestingly, Dunn et al. (2002) reported that exclusion was related to higher levels of both internalizing and externalizing behaviors, and Leake found that the presence of stepsiblings decreased contact with the nonresident parent, which continued into young adulthood (Ward, Spitze, & Deane, 2009).

Unfortunately, much less is known about these sibling interactions and perceptions in other types of stepfamily structures, although some evidence suggests higher negativity and exclusion (Sweeney, 2010). Clearly, more research on sibling relationships in diverse stepfamilies is needed. To this end, Baham et al. (2008) provided a testable model to guide these endeavors. They assert that psychosocial outcomes are influenced by the various child and family demographic characteristics, and that the quality of the parent–child relationship is mediated by the quality of sibling relationship. Given the lack of previous research, studies that test this model may provide meaningful insights.

Experiences of Gays and Lesbians in Stepfamilies

Since 1999 there has been a slight increase in the number of published research studies examining the experience of gays and lesbians in stepfamilies, consistent with calls from scholars to study stepfamily diversity more (e.g., Coleman et al., 2000). However, the need to understand these families is more important now, given recent changes in how stepfamilies are conceptualized in general and the changing legal situations for gays and lesbians regarding partnership, marriage, and adoption laws (Robson, 2001), as well as advances in reproductive technologies (e.g., van Dam, 2004).

Research on gay and lesbian stepfamilies most often has focused on those formed when one or both partners have a child from a prior heterosexual marriage that ended in divorce (e.g., Berger, 2000; Crosbie Burnett & Helmbrecht, 1993). Conceptualizing stepfamilies as including those formed after a prior marriage and those formed through prior cohabiting relationships, consideration of the diverse pathways by which gay and lesbian stepfamilies are formed and how these pathways differentially influence stepfamily life is needed. Because the number of family transitions experienced is linked with the possibility of negative outcomes (Demo, Aquilino, & Fine, 2004), the general literature on gay and lesbian relationships often fails to ask about previous cohabiting unions. When this information was garnered, both types of couples were included together in analyses without controlling for prior union influences. From an inclusive perspective, gay and lesbian couples in current cohabiting relationships or marriages with at least one prior cohabiting relationship or marriage are considered a repartnership or a stepfamily when a child from a previous union is present, regardless of how the child was conceived.

Previous research suggested differences in relationship processes and outcomes by type of heterosexual family structure (e.g., Bradbury, Fincham, & Beach, 2000; Brown & Booth, 1996). Other research suggested similarity between gay and lesbian couples and heterosexual married couples (e.g., Kurdek, 2004, 2006). Although there is limited comparative data between heterosexual and gay and lesbian couples, little is known about the diversity of gay and lesbian families in general, and even less is known about gay and lesbian repartnerships and stepfamilies particularly. Certainly it follows that much can be done in the future to better understand the experiences of these families; however, efforts to better conceptualize and theorize within-group diversity among gay and lesbian families is needed.

Aside from research suggesting similarity between gay and lesbian families and their heterosexual counterparts, recent research has provided some additional insights into gay and lesbian stepfamilies specifically. For example, Berger (2000) suggested that gay male stepfamilies are stigmatized for being gay, for being a stepfamily, and for being parents, and this stigma can negatively influence stepfamily functioning (e.g., Crosbie Burnett & Helmbrecht, 1993). Other research suggests that this negative influence might be more indirect than direct. For example, Lynch (2000) interviewed 17 lesbian and 6 gay stepfamilies and found that parents in stepfamilies experienced difficulty integrating their gay/lesbian and parenting identities which resulted in reduced family functioning. Other evidence suggests that the lack of legal connections may further exacerbate these difficulties (Moore, 2008; Robson, 2001). Certainly, legal ambiguity can strain both the couple and the step/parent–child relationships. In fact, results from a longitudinal study (Hatzenbuehler, Keyes, & Hason, 2009) showed that, over 12 months, gays and lesbians experience more psychological distress when they lived in states without supportive and protective policies specific to them. It might be that geographic location (serving as a proxy for state-level policies) moderates the link between stress and various family outcomes in gay and lesbian stepfamilies. Also, potential mediators of stress might include process around certain family functions, parenting interactions, and couple dynamics.

Children living in gay and lesbian stepfamilies report more stigmatization from having gay or lesbian parents than from being part of a stepfamily (Robitaille & Saint-Jacques, 2009). Further, reports from interviewing 11 children indicated that most identified internalizing the stigma experienced which resulted in ambiguity concerning when and how to disclose their family structures; most decided to not disclose (Robitaille & Saint-Jacques). Unfortunately, van Dam (2004) found that adults in lesbian stepfamilies earned lower wages, were younger, had less education, came out later, and were less likely to be involved in gay and lesbian family organizations than were lesbian mother families. Although all of these factors increase the risk and vulnerability of lesbian stepfamilies, they also are characteristics consistent with their heterosexual counterparts (Coleman et al., 2000). Interestingly, there is no research to suggest these risks translate into detrimental outcomes for these families. As such, more research that focuses on the resilience of gay and lesbian stepfamilies is needed, especially that which focuses on the identification of protective factors for the adults and children involved.

Communication and Conflict

Much of what we have discussed about stepfamily living included aspects of communication and conflict underlying family interactions, especially around step- and coparenting processes. In fact, greater attention has been paid to communication and conflict in recent research than in the past (see Coleman & Ganong, 1990; Coleman, et al., 2000). Generally, the potential for conflict is greater in stepfamilies than first married families (Pasley & Lee, 2010), although the top two sources of conflict identified by both groups are the same (children/stepchildren and finances) but the order is different (Stanley, Markman, & Whitton, 2002). That is, remarried couples report children as being the primary source of conflict, whereas first-marrieds report money as the primary source. This increased potential for conflict around children/stepchildren stems from issues with former spouses (e.g., Adamsons & Pasley, 2006; Ganong & Coleman, 2006) and about parenting/stepparenting or the relationship between stepparents and stepchildren (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002; Shelton, Walters, & Harold, 2008), especially stepdaughters and stepfathers or when the stepchild is an adolescent (e.g., Feinberg, Kan, & Hetherington, 2007). Understandably, conflict also often is focused on issues specific to rule setting and boundaries as these new families form (Afifi, 2008).

From studies using only stepfamily samples, and thus adopting a normative–adaptive approach, results indicate that open communication and flexibility is predictive of the ability to negotiate new rules and boundaries and deal with loyalty conflicts (Golish, 2003). Other results indicated that these families also have a higher probability of successful stepfamily development (e.g., Braithwaite, Olson, Golish, Soukup, & Truman, 2001). Not surprising, primary communication about everyday life and problems rather than unintrusive small talk occurs more frequently between resident parents and children than between children and stepparents or nonresident parents (Schrodt et al., 2007). However, in their study that included all family members, no differences in the use of conflict were found between children and any type of parent. Alternatively, studies find that avoidance can deter stepfamily development, and that the use of avoidance communication techniques are higher among stepfamilies compared with first-married families (Halford et al., 2007) and among adolescents and young adults in stepfamilies (Golish & Caughlin, 2002).

The influence of communication and conflict on individual, couple, and family adjustment also received considerable attention recently. For example, among men and women, the spouse’s perceived communication abilities predicted marital satisfaction, and the strength of this relationship was stronger for men (Beaudry et al., 2004). Further, age and number of children from previous unions and income level moderate this link—a finding consistent with other studies (Gosselin & David, 2007). The nature of the remarital relationship also is influenced by conflict with former spouses and stepchildren. Interparental conflict has strong links to mother–child and stepfather–stepchild conflict (Dunn, Cheng, O’Connor, & Bridges, 2004), and more frequent stepfather–stepchild conflict is linked with more frequent child involvement in stepfamily arguments and siding with their mothers (Dunn, O’Connor, & Cheng, 2005). Certainly, this creates potential for feedback loops to occur that likely undermine family adjustment if continued, and there is evidence to support this (Ruschena, Prior, Sanson, & Smart, 2005). Alternatively, when relationships are not laden with conflict, stepfamily and individual adjustments are better (Greff & Du Toit, 2009; Yuan & Hamilton, 2006).

Interestingly, Shelton et al. (2008) showed that the mechanism through which interparental conflict affected children differed for those in first-married and remarried families. Specifically, those in first-married families were affected by perceived threat and their own experiences with self-blame. For children in stepfamilies, findings were that neither threat or self-blame affected their outcomes. However, when conflict between mother and stepfather resulted in more hostile and rejecting parenting/stepparenting, the child was negatively affected. Studies such as this one demonstrate the increased sophistication of the research questions asked and answered, as scholars seek to understand the mechanisms through which certain factors influence outcomes and adjustment processes for all involved in stepfamily life.

The Broader Social Context

Three areas outside of immediate family relationships have garnered the attention of scholars as influential to family processes within stepfamilies. These areas include extended family members (i.e., grandparents), societal views (e.g., stigmatization and stereotyping), and the legal context.

Grandparenting in Stepfamilies

Bengston (2001) and others (e.g., Johnson, 2000) argued for the inclusion of a multigenerational component in the conceptualization of family, partially because of changes due to remarriage and stepfamily life witnessed in the past. From a social capital perspective, grandparents and stepgrandparents can play a significant role in child adjustment to stepfamily life and to other life transitions (Demo et al., 2004). Few studies occurred before 2000, and their primary focus was on the nature and role of step-/grandparent–step-/grandchild relationships, particularly changes in grandparent–grandchild relationships post-divorce and into remarriage. Although limited, research published in this decade relied almost entirely on convenience samples (e.g., Christensen & Smith, 2002; cf. Lussier, Deater-Deckard, Dunn, & Davies, 2002), whereas later publications relied on analyses of existing longitudinal data (e.g., Bridges, Roe, Dunn, & O’Connor, 2007; Ruiz & Silverstein, 2007; cf. Attar-Schwartz et al., 2009).

Generally, this body of research suggests that grandparent–grandchild dyads experience reduced contact post-divorce (Bridges et al., 2007) and after a parent’s remarriage (Ruiz & Silverstein, 2007). Further, this reduction in contact is highest when the grandparent’s adult child is the nonresident parent (Lussier et al., 2002). However, the quality of these relationships is less affected by family transitions and changes in structure. Most studies find no negative reductions in relationship quality (e.g., closeness, cohesion, satisfaction) over time from longitudinal data (Bridges et al., 2007) or from cross-sectional data (Lussier et al., 2002). One study using Wave 2 data from the NSFH did find that remarriage was negatively linked with the quality of the grandparent–grandchild relationship (Ruiz & Silverstein, 2007).

It may be that overtime the initial negative effect on the quality of this relationship stabilizes and is reduced. In fact, some research (Attar-Schwartz et al., 2009) found that the presence of a grandparent was linked with enhanced adjustment and reduced internalizing symptoms (Lussier et al., 2002; Ruiz & Silverstein, 2007) in grandchildren. However, such effects may vary by age, sex, and status of the grandparent. For example, Block (2002) found that grandmothers were perceived by stepgrandchildren to be more supportive than stepgrandfathers, and other research found that younger grandparents perceived the relationship to be higher quality compared to older grandparents (Christensen & Smith, 2002). However, stepgranddaughters reported their relationship with stepgrandparents to be of higher quality compared with stepgrandsons, and stepgrandfathers reported more conflict with stepgrandchildren than stepgrandmothers.

Overall, we speculate that grandparents and stepgrandparents are an untapped resource to other family members. However, more research is needed to understand such possibilities.

Societal Views

The decade reviews of the 1990s, Coleman et al. (2000) presented findings from a number of studies addressing societal views of stepfamilies. Overwhelmingly, the results of these studies (e.g., Ganong & Coleman, 1997; Levin, 1993) indicate that participants viewed stepfamilies negatively. Beyond stigmatization, there was research suggesting that they were invisible to other social contexts (e.g., schools, Crosbie-Burnett, 1994). There is also past research showing fewer norms for steprelationships regarding obligations and other role expectations (Grizzle, 1999), with similar results appearing in more recent studies (Coleman, Ganong, Hans, Sharp, & Rothrauff, 2005; Ganong & Coleman, 2006).

Interestingly, stereotypes about stepfamilies continue to be a topic of empirical studies. For example, Claxton-Oldfield, Goodyear, Parsons, and Claxton-Oldfield (2002) surveyed two groups of college undergraduates (N = 99) and found that they were likely to suspect stepfathers of sexual abuse more than biological fathers. Other contexts showed similar negative stereotyping. For example, a content analysis of 27 commercially produced films (Leon & Angst, 2005) that included stepfamilies showed that half of the movies portrayed stepfather families, with about 39 % depicting stepfamilies in an entirely negative manner. Almost 35 % of these films depicted stepfamilies in both positive and negative ways. Moreover, a recent study (Planitz & Feeney, 2009) of two samples provided results suggesting that children believe the negative stereotypes about stepfamilies, especially those revolving around conflict and negativity. Certainly, children who are exposed to such stereotypes and then enter a stepfamily are likely to experience a more difficult transition, potentially undermining the union formation itself.

Legal Context

Consistently, there has been little research addressing legal or social policy applied to stepfamilies and their members over time (see Coleman & Ganong, 1990; Coleman et al., 2000; Sweeney, 2010). Kisthardt and Handschu (1999) and Mahoney (2000) reviewed a variety of legal issues specific to stepparents who want to maintain contact or gain custody over a stepchild following divorce or death of the parent. They suggested that stepparents have almost no legal standing. Mason (2001) reviewed the area of family law specific to stepfamilies for the preceding 3 decades and concluded that stepparents and stepchildren have few family rights, thereby placing them at risk. From the stepparent’s perspective, there are benefits in being afforded legal recognition, and stepparents report a desire for such benefits (Mason et al., 2002); yet legally, they more often perceive themselves as invisible parents during court proceedings (Gately et al., 2006). Clearly, this remains an area requiring more attention and advocacy.

Methodological and Theoretical Trends

Although we have mentioned methods and theories as part of other sections in this chapter, here we present a broader look at trends in these two areas. As with most substantive areas of research, both the methods and theories used became more sophisticated and complex. Given the changing nature of families, new methods and theories are needed to address such changes, and scholars have applied this argument to remarrieds and stepfamilies (Coleman & Ganong, 1990; Coleman et al., 2000; Pasley & Moorefield, 2004). As Coleman and Ganong (1990) cautioned, conceptual advances also influence the choice of methods and theory. For example, conceptualizing remarriage (with or without the presence of children) as a dynamic event which unfolds overtime is consistent with two comprehensive models of stepfamily development (Papernow, 1993) and adjustment (Fine & Kurdek, 1994b). Conceptualizing remarriage and stepfamily adjustment as processes overtime and across households requires the use of longitudinal methods and family process theories (e.g., life course, family systems) which is evident in more recent research efforts (see Sweeney, 2010 for a summary), and this produced a depth of knowledge not witnessed earlier. Accordingly, the use of multimethod approaches increased slightly since 2000, as has the use of sophisticated data analytic techniques (e.g., latent grow curve modeling and HLM approaches; see Langenkamp, 2008, as an example). However, we argue that much of the literature lacks attention to both methods and theory. We then discuss some of the basic methodological and theoretical issues and trends noted in this body of work, with emphasis on the last 10 years.

Methodological Issues and Trends

Overtime the use of data from longitudinal studies has become increasingly common (e.g., ALSPAC, Add-Health, NELS, NSFH, the Virginia Longitudinal Study of Divorce and Remarriage). As new waves of data become available, we expect their use will continue. When longitudinal data are available, multiple waves should be used rather than relying on only a single wave of data, as is common. Although panel data allows for some level of causal inference, several limitations to generalizability exist, especially regarding remarriage and stepfamilies. For example, scholars suggest that stepfamilies are less likely to participate in research (Hobart & Brown, 1988) often due to the stigma from stereotypes about them (Coleman & Ganong, 1987); they are more mobile, increasing their attrition from participation in a longitudinal efforts (Spanier & Furstenberg, 1982); and there is difficulty identifying correct addresses when using marriage license records (Clingempeel, 1981; Hanzal & Segrin, 2008). Additionally, samples tend to be overrepresented by those who are White, middle-class, and highly educated, as well as including responses from a single family member.

Given the large number of questions asked of respondents in panel studies, the depth of the information obtained can be problematic. For example, large studies often lack information on relationship histories, making it difficult to ascertain particular subsamples and distinguish certain family relationships and structures; some first-married families may actually be stepfamilies, if prior cohabiting information was available. Also, family processes (e.g., relationship quality, communication) are not measured adequately (Coleman et al., 2000; Pasley & Moorefield, 2004). Further, the use of secondary data limits the questions that can be asked and, accordingly, the theories used to explain them. Certainly, the benefits of having such data outweigh the deficits, but such issues suggest a need to initiate new studies to overcome some of these problems, if greater insight into stepfamily life is to be forthcoming. In fact, some advances in measurement have been made recently, as with the development and validation of the Stepfamily Life Index (Schrodt, 2006a) and the Stepparent Relationship Index (Schrodt, 2006b).

The depth of our understanding about the experiences of stepfamilies has improved greatly with our increased use of diverse methods, such as qualitative interviewing (e.g., Marsiglio & Hinojosa, 2007; Weaver & Coleman, 2005) and observational approaches (Halford et al., 2007). The use of daily diaries (e.g., Moore, 2008; O’Brien, Delongis, Pomaki, Puterman, & Zwicker, 2009), the Internet to obtain samples (e.g., Johnson et al., 2008), and mixed methods (Langenkamp, 2008) are evident in recent studies of stepfamilies. The diversity of methods that is now becoming evident is promising and should enhance both our theory development and understanding of the phenomena.

Theoretical Trends

Theoretically, the extant literature on remarriage and stepfamilies predominantly relied on either implicit use or no use of theory (Coleman et al., 2000), and this has continued (e.g., Bir-Akturk & Fisiloglu, 2009; Hanzal & Segrin, 2008). Consistent with suggestions from others (e.g., Coleman et al., 2000; Price Bonham & Balswick, 1980), we believe that scholars need to explicitly use theory to guide their research, continue to refine existing theories, and develop new theories to better explain the complexity of stepfamily life. The increased use of grounded theory (e.g., Brimhall, Wampler, & Kimball, 2008; Marsiglio & Hinojosa, 2007; Sherman & Boss, 2007) has resulted in a more rich understanding of these families, but much of this work has not informed larger, quantitative studies. For example, Brimhall et al. developed a model suggesting that trust plays an important role in mediating the effect of a previous marriage on current remarriages. Testing the findings with larger samples is an important next step, especially in understanding variation among those in remarriages and stepfamilies.

Our intent in making these observations is not to suggest that theory use has been scant. In fact, studies have generated and tested several important theoretical hypotheses and models that are influential in this literature. We summarize this literature in two tables. In Table 22.1 we provide an overview of the most widely used hypotheses and models. Due to space limitations we do not offer a thorough discussion (see Coleman & Ganong, 1990; Coleman et al., 2000; Stewart, 2007, for a more complete discussion), but we do offer a basic explanation of each theory with sample references. In Table 22.2, we provide an overview of theories commonly used in this literature with examples of research questions and citations for further reading. Our purpose in constructing these tables is to demonstrate the explicit connection between theory and research in this literature.

Based on our review, we believe that certain theories hold the most potential for increasing our understanding of remarriage and stepfamilies, especially their diversity, variations in family processes, and successful stepfamily development. These theories include stress perspectives, grounded theory, family systems theory, life course theory, and risk and resiliency theory. Lastly, as evident in both tables, the majority of the theoretical work focuses on children in stepfamilies. As such, the development and use of theories to better understand and explain couple relationships and the multiple pathways of relational development deserves more attention in the future.

Conclusions

Since the 1980s, there are many consistent findings regarding remarriages and stepfamilies and consistency in many of the methods and theories used. In fact, although many questions asked since 1999 have been largely similar to those asked earlier, we have more confidence in many of the findings because of the methods and theories used. Overwhelmingly, the extant literature has focused on children rather than relational dynamics, so we have greater confidence in the findings related to children in general and child outcomes specifically. Ideologically, the literature on child outcomes upholds the advantages of being reared in a nuclear family. However, from a pluralistic perspective the opposite is true, and we believe that assuming a pluralistic perspective is consistent with the diversity of families in the twenty-first century (Levin, 1999). Following, we summarize some of the key consistencies across these two views and highlight a few areas to guide future research.

Compared to those in nuclear families, adults in remarriages and stepfamilies experience largely similar levels of well-being, life satisfaction, and marital quality. In spite of this, those in remarriages have slightly higher probabilities of redivorce, and this likely is most related to problems associated with stepchildren and being a stepparent. We believe there is good evidence across studies to support a bidirectional effect of remarital and stepparent–stepchild relationships. Although adjustment to life in a stepfamily is difficult and prone to more conflict, particularly related to defining the stepparent role and interacting with stepchildren, many stepfamilies adjust well overtime (Gosselin & David, 2007). The academic, social, and psychological outcomes of children in stepfamilies are lower than those reared in nuclear families (Amato, 1994; Jeynes, 2006). However, these differences are small and of limited practical meaning, even when statistically significant. On average, children in stepfamilies tend to do well over time and into adulthood. Age of children, sex of children, match of sex between stepparent and stepchild, and duration of remarriage all moderate these outcomes (Bray & Kelly, 1998; Falci, 2006; Golish & Caughlin, 2002; Schmeeckle, 2007).

In the past few years we have learned more about the diversity and complexity of stepfamilies (e.g., Johnson et al., 2008; Tillman, 2007). It appears that diversity and complexity moderate many of the above outcomes with those in cohabiting stepfamilies faring worse than those in legal stepfamilies. However, greater understanding of these cohabiting stepfamilies and other stepfamily variations, especially those of different races/ethnicities and sexual orientations, is required in the future (cf. Stewart, 2007).

We continue to know much less about successful stepfamilies. We concur with others (e.g., Coleman et al., 2000) that a shift in focus is needed to glean insight into how some stepfamilies develop successfully rather than focusing on deficits. However, this shift was not apparent in a good number of the studies in this recent decade (see Sweeney, 2010). Using family process-related theories and those that incorporate family systems perspectives in concert with more observational methods may serve us well here. That said, we do know of several factors that appear to enhance successful stepfamily development. For example, adoption by a stepparent (Schwartz & Finley, 2006) and cooperation between a stepparent and nonresident parent (Marsiglio, 2004; Robertson, 2008) seem to ease transitions and enhance child adjustment and outcomes. Changes in family laws that allow legal recognition of stepparents might aid adjustment, as might participation in educational programs directed toward both parenting within and coparenting across and within households (Adler-Baeder & Higginbotham, 2004; Mason et al., 2002). However, more research is needed to better support any legal suggestions we might advocate, and this is consistent with a general need to better understand the interface between stepfamilies and social institutions. Importantly, there is growing evidence that specialized programs that address parenting processes and stepfamily adjustment are also helpful (e.g., Whitton, Nicholson, & Markman, 2008), but more research is needed. Clearly, family systems, ecological, and feminist theories are positioned well to guide such studies.

Taken together, we believe that stepfamilies are functioning well in spite of the many challenges they experience both within their family system and within the broader social and legal contexts. Such resilience is an important stepfamily strength and one that we hope scholars will dedicate more energy toward understanding in the future.

References

Adamsons, K., O’Brien, M., & Pasley, K. (2007). An ecological approach to father involvement in biological and stepfather families. Fathering, 5, 129–147.

Adamsons, K., & Pasley, K. (2006). Coparenting following divorce and relationship dissolution. In M. A. Fine & J. H. Harvey (Eds.), Handbook of divorce and relationship dissolution (pp. 241–262). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Adler-Baeder, F. (2006). What do we know about the physical abuse of stepchildren? A review of the literature. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 44(3–4), 67–81.

Adler-Baeder, F., & Higginbotham, B. (2004). Implications of remarriage and stepfamily formation for marriage education. Family Relations, 53, 448–458.

Afifi, T. D. (2008). Communication in stepfamilies. In J. Pryor (Ed.), The international handbook of stepfamilies: Policy and practice in legal, research, and clinical environments (pp. 299–322). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Ahrons, C. R. (2007). Family ties after divorce: Long-term implications for children. Family Process, 46, 53–65.

Amato, P. R. (1987). Family processes in one parent, stepparent, and intact families: The child’s point of view. Journal of Marriage and Family, 49(327), 337.