Abstract

Urethral bleeding is a relatively common reported event. Different etiologies characterize this symptom in males and females. In the male patient, urethral bleeding may suggest a urethral injury requiring urgent hospital referral. Other common causes of male urethral bleeding are linked to sexually transmitted diseases such as urethritis and condylomata of the urethral meatus. In a significant proportion of patients, the etiology of urethral bleeding will remain unknown, yet a urological referral is advisable to rule out the rare possibility of urethral neoplasms. In the female patient, it is usually more difficult to ascertain the urethral origin of bleeding because of possible confusion with an underlying gynecological (vulvovaginal or uterine) disease. Urethral examination usually helps to rule out benign conditions such as caruncles and diverticula as well as the rare occurrence of urethral neoplasms. In both sexes, the presence of urinary incontinence makes the differential diagnosis with hematuria difficult; hence, patients should be investigated accordingly. Unusual sexual practices that involve transurethral insertion of traumatic foreign bodies should always be kept in mind when considering urethral bleeding. A practical algorithm is provided to help the general practitioner in making decisions about female and male urethral bleeding.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Urethral bleeding is defined as the occurrence of bleeding from the urethra separate from micturition. Patients should be asked to describe the circumstances when they noticed urethral bleeding in order to make sure they are not describing an episode of hematuria.

In a male patient, blood stained underwear in the area that is in contact with the penis is highly suggestive of urethral bleeding, after lesions in the genital skin or the gland have been excluded. Sometimes the patient has noticed one or more drops of blood pouring out of the urethral meatus not during episode of micturition. Spontaneous bleeding from the urethra implies that the site of origin of bleeding is distal to the striated sphincter, i.e., comprised in the bulbar, penile, or glandular urethra.

In the female, it is usually difficult, based only on the history of the patient, to discriminate between bleeding of uterine, vaginal, or vulvar origin (the far more common causes of bleeding) and urethral bleeding. A careful gynecological examination will help in the differential diagnosis.

For both sexes, when urine incontinence coexists, it becomes difficult to rule out bleeding from the urinary tract; hence, the patient should be investigated for hematuria.

Hints to Find a Cause for Urethral Bleeding

Table 10.1 lists the most common causes of urethral bleeding along with particular characteristics relating to the patient’s history and the examination. It should be noted that, in spite of all the diagnostic investigations, in the majority of cases, the precise etiology of urethral bleeding will remain unknown.

The most common situation is minor trauma of the bulbar-penile urethra, usually occurring after the urethra is hit by a kick at the level of the penis or perineum. If the patient is able to void his bladder without significant pain and the urethral bleeding rapidly self-resolves, conservative management can be safely adopted. Any more complex situation should be referred to the A&E.

The management of complex urethral injuries is usually conservative, leaving a transurethral or suprapubic catheter in place. Complete urethral lacerations, particularly when associated with severe bleeding, may be treated with immediate surgical realignment of urethral stumps. Most urethral injuries will heal with a urethral stricture causing obstructive urinary symptoms. This complication needs to be promptly recognized, and the patient should be sent to the urologist for treatment.

Management of Urethral Bleeding in the GP’s Office

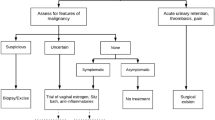

Comments About Flowchart 10.1

-

1.

A male patient describing urethral bleeding should be asked about the circumstances in which the symptom occurred (urethral injury, masturbation practices) and whether other symptoms are associated (chiefly urinary symptoms such as dysuria, frequency, difficulty in passing urine, and so on). Discussing sexual history will help to know whether to suspect sexually transmitted diseases. Inspection of the external genitalia is aimed at excluding penile or perineal hematomas (suggestive of trauma), ulcerations on the genital skin, and lesions of the glans and the urethral meatus. Milking of the urethra allows the GP to exclude the presence of urethral discharge. Indurations or nodules at the level of penile and bulbar urethra can be felt with palpation.

-

2.

If patient has a history of urinary incontinence, it may be difficult to ensure that the blood staining the pad or seen coming out of the urethra is not actually originating from the urinary tract above the urethral sphincter. In this case, the presence of hematuria cannot be ruled out and the patient should be investigated accordingly (see chapter on macroscopic hematuria).

-

3.

If urethral bleeding is the consequence of a urethral injury, some degree of urethral disruption has occurred. The possibility of self-inflicted urethral trauma by psychiatric patients or as a consequence of masturbation practices should always be suspected. It is imperative to refer the patient to the A&E unit, particularly when urinary difficulties or penile and perineal hematoma are associated. Any suspicion of the presence of foreign bodies in the urethra or the bladder can be ruled out with a simple X-ray of the pelvis. Conservative management without hospital referral can be adopted in cases of minimal and rapidly self-resolving bleeding with no urinary difficulties. The patient should be counseled on the significant risk of developing a urethral stricture following any urethral trauma accompanied by urethral bleeding.

-

4.

When urethral bleeding is not accompanied by other symptoms, no traumatic event is reported, and no sign of urethral diseases can be found during examination, the patients should firstly be reassured. The cause of the disease will most probably remain unknown. A urological referral is however wise to rule out the rare occurrence of a urethral polyp or urethral carcinoma by an endoscopic evaluation of the urethra (urethroscopy).

-

5.

Dysuria associated with urethral discharge leads to the suspicion of urethritis. Testing for gonorrhea, chlamydia, and gram stain for gram-negative diplococci and polymorphonucleates is recommended. This can be done on a sample of urethral discharge obtained through urethral milking or endourethral swab. Chlamydia is currently more accurately detected via a nucleic acid amplification test on a sample of the first-catch urine. Alternatively, patient with suspected urethritis can be referred to a sexually transmitted disease clinic.

-

6.

Persistence of urinary symptoms and urethral bleeding after antibiotic therapy warrants a urological referral. The same applies to condylomata detected at the urethral meatus, which are usually managed with endoscopic evaluation of the urethra, biopsy for viral subtyping and fulguration.

Comments About Flowchart 10.2

-

1.

The diagnostic algorithm in cases of suspected urethral bleeding in a female can be extremely simplified, focusing on deciding the most appropriate specialist for referral.

-

2.

History and examination of the patient should be oriented to determining whether the bleeding is more likely to be due to a urethral disease or has a genital (uterus, vaginal, or vulvar) origin. The female urethral meatus should be carefully inspected for the presence of urethral caruncles or urethral polyps. Any abnormality of the whole urethra can be felt by digital inspection of the anterior vaginal wall. A lump or induration of the urethral contour suggests a urethral origin. Vulvar inspection and digital examination of the vagina and cervix can help to identify genital sources of bleeding.

-

3.

Any abnormality during the inspection of the urethral meatus or following digital examination of the anterior vaginal wall warrants a urological referral. A urethral caruncle usually presents as a reddish, soft, polypoid growth protruding from the urethral meatus. Urethral diverticula or paraurethral cysts (arising from embryological Mullerian remnants) are not uncommon findings and usually appear as lumps bulging from the urethra, with a regular surface and of soft consistency. Primary or metastatic urethral neoplasms are rare and appear as irregular, hard alterations of the urethral profile. Incontinent patients, like their male counterparts, should be investigated for hematuria to rule out the possibility of bleeding from the urinary tract. Bleeding from the urethra may often be associated with various urinary symptoms, unlike genital bleeding.

-

4.

When history and examination of the patient are in keeping with a low probability of urethral origin of the bleeding (no urinary symptoms with a normal-looking urethral meatus and absence of palpable urethral abnormalities in a continent patient), it may be reasonable to refer the patient to the gynecologist in the first instance. This is particularly true when a genital source of bleeding is clearly demonstrated.

Conclusions

Urethral bleeding is a urological symptom to be managed with a careful history-taking and a scrupulous clinical examination in the GP’s office. By doing so, the majority of identifiable underlying etiologies can be suspected. The rare possibility of a urethral malignancy should always be kept in mind. It is advisable to refer most male patients to the urologist. The choice of the most appropriate specialist referral for the female patient – urological or gynecological – depends very much on the findings of the genital examination.

Bibliography

Conces MR, Williamson SR, Montironi R, Lopez-Bertrand A, Scarpelli M, Cheng L. Urethral caruncle: clinicopathologic features of 41 cases. Hum Pathol. 2012;43(9):1400–4.

Huguet Pérez J, Errando Smet C, Regalado Pareja R, Rosales Bordes A, Salvador Bayarri J, Vicente Rodríguez J. Urethral condyloma in the male: experience with 48 cases. Arch Esp Urol. 1996;49(7):675–80.

van der Horst C, Martinez Portillo FJ, Seif C, Groth W, Jünemann KP. Male genital injury: diagnostics and treatment. BJU Int. 2004;93(7):927–30.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer-Verlag London

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gontero, P. (2013). Urethral Bleeding. In: Gontero, P., Kirby, R., Carson III, C. (eds) Problem Based Urology. Springer, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-4634-6_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-4634-6_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-4471-4633-9

Online ISBN: 978-1-4471-4634-6

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)