Abstract

Mania is a rare consequence of stroke, and according to the sparse published information, it is difficult to describe its demographic, clinical, and prognostic characteristics. We defined poststroke mania as a mood disorder characterized by an elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, pressured speech, distractibility, grandiosity, hyperactivity, and disinhibition. The diagnosis is based on DSM-IV-TR and Krauthammer and Klerman criteria. A recent systematic review of all cases of poststroke mania allows the collection of 49 studies describing 74 cases. Although there are some cases of mania after left-sided strokes, the majority of cases referred to right-sided lesions. These lesions were more frequently located in the area of orbitofrontal circuit that includes the orbitofrontal cortex, the basotemporal region, the thalamus, and the caudate nucleus. This circuit is crucial for mood regulation and social behavior. The typical patient with mania associated to stroke was a male, without personal/family history of psychiatric disorder, with at least one vascular risk factor, without subcortical atrophy, and with a right cerebral infarct. Similar to primary mania, treatment consists of mood stabilizers and typical or atypical antipsychotics. Mania has high potential disruptive impact after stroke, during the acute care and in the post-acute and rehabilitation phase.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Poststroke mania

- Mood disorder, DSM-IV-TR

- Elevated, expansive, or irritable mood

- Increased rate or amount of speech

- Overactivity

- Flight of ideas

- Grandiose ideation

- Orbitofrontal circuit

- Mood stabilizers

- Antipsychotics

Definition

Mania is the main symptom for the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, a mood disorder with a prevalence in community studies between 0.4 and 1.6 % and which causes a significant personal and social impairment [1]. Mania is characterized by affective disturbances, such as an elevated, expansive, or irritable mood; changes in speech, with an increased rate or amount; disturbances in language thought and content, with flight of ideas, grandiose ideation, and lack of insight; and behavioral disturbances characterized by overactivity and social disinhibition [1–4]. Primary mania refers to the psychiatric condition itself without a documented brain lesion, and secondary mania describes the manic symptoms caused by neurological, metabolic, or toxic disorders [5]. The term secondary mania was introduced by Krauthammer and Klerman in 1978. Starkstein et al. did not find significant differences between primary and secondary mania clinical profiles [6].

DSM-IV-TR presents the criteria for mood disorder due to a general condition. These criteria should be used for the diagnosis of depression and/or mania after stroke. In Table 4.1, we present the DSM-IV-TR criteria and also the Krauthammer and Klerman criteria for secondary mania.

The literature of mania after stroke is composed predominantly by case reports, small case series, and a few systematic studies. Although mania can be very disrupting during stroke hospitalization and recovery, its low prevalence limits the description of its clinical, demographic, and prognostic features and the identification of evidence-based strategies for dealing with it. Recently, we performed a systematic review of all cases of mania associated with stroke, published until December 2010, aiming to answer to those questions, in order to increase the robustness of the evidence of this neuropsychiatric complication of stroke [7].

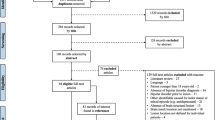

We included studies that were required to fulfill the following inclusion criteria: (1) all cases of mania associated with stroke; (2) patients with diagnosis of cerebral infarct (INF), intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), or subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH); and (3) adult patients (≥18 years old). From 265 abstracts identified by electronic search, reference lists of the studies collected, and handbooks of neuropsychiatry of stroke, 139 were potentially relevant, of which 49 studies (35 %) met the inclusion criteria. These 49 studies describing 74 cases of poststroke mania were included in the first analysis to determine the most important characteristics of those cases. In a second analysis, from those 49 studies, we selected 32 studies (49 cases), corresponding to cases in whom an explicit temporal and causal relationship between manic symptoms and stroke was documented. The results and conclusions of the systematic review will be discussed throughout this chapter along with data from previous studies and case reports.

Epidemiology

Mania is a rare consequence after stroke and its prevalence seems to be around 1 % [8]. In large community-based studies, such as the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project and the Perth Community Stroke Study, no cases of poststroke mania were found [9, 10].

In 1922, Babinski first associated a right hemispherical lesion with euphoria, indifference, and anosognosia [11]. Since then, nearly a hundred cases have been described. In our systematic review, we had confirmed the rarity of poststroke mania, identifying only 74 cases of adult stroke patients with mania symptoms published since the 1970s (Table 4.2).

Cohen and Niska described a case of a 59-year-old man, who 2 years after a right temporal hematoma presented manic symptoms, compatible with secondary mania criteria [58]. Jampala and Abrams reported the cases of a 52-year-old man and a 40-year-old man admitted with mania after a left and right hemispherical stroke lesion, respectively [57]. After a review of the cases with mania and the type and location of intracerebral lesions, the authors questioned the association between mania and right lesions. One year later, Cummings and Mendez strengthened the relationship between right hemispheric strokes and mania, while presenting two patients with lesions in the right thalamus, followed by mania [56].

In successive studies, Starkstein et al. collected the highest number of poststroke mania patients. Until 1987, the authors found only three patients with mania among 700 stroke patients [8]. In 1987, they included 11 consecutive patients in a group of secondary mania, four of whom had stroke [6]. The same authors performed a series of studies about mania and depression and collected 17 patients with mania, of whom 9 with a stroke [61].

Caeiro et al., in a study of neuropsychiatric disturbances in consecutive acute stroke patients, investigated the presence of mania, using the Mania Rating Scale (MRS) [27]. MRS is a widely used mania scale with 11 items, in which mania is operationally defined if patients score at least 12 points [62]. Of the 188 patients, with a mean age of 56.9 and a mean of 6.6 years of education, only one (0.5 %) fulfilled the criteria for mania. This patient presented emotional and behavioral changes characteristic of a manic episode, such as an elevated mood, talkativeness, overactivity, and denial (Case 1).

Celik et al. described a case of a 69-year-old woman with vascular risk factors that after a right temporoparietal stroke had an acute change in her behavior with manic symptoms [22]. Nagaratnam et al. studied two patients with secondary mania following left- and right-sided infarctions [19]. Rocha et al. followed a 47-year-old woman without personal or familiar history of psychiatric disorder and with a right medial frontal lobe, which seems to cause elated mood, irritability, agitation, pressured speech, grandiosity, insomnia, and denial [18].

Mania can manifest in the acute phase but there are reported cases of mania until 2 years after stroke [8]. In fact, the majority of mania cases appeared in the first days after stroke, with 53 % immediately after stroke, 23 % during the first month after stroke, and 23 % after this first month. This delayed presentation may cause difficulties in the identification of manic symptoms.

As stated earlier, the clinical profile of poststroke mania is very similar to the symptom profile of primary mania. We found that the first symptom of mania associated with stroke is the presence of elevated mood, which in some cases alternates with an irritable mood. Other frequent symptoms are an increased rate or amount of speech, insomnia, and agitation. We also counted the number of core symptoms of mania and found that the majority of the patients presented five or more symptoms of mania. The difference between primary and secondary mania seems to be the symptom duration, which is longer in secondary mania probably due to the presence of other comorbidities and the usage of lower doses of antimanic agents.

Risk Factors

Since the first reported cases, the association between poststroke mania and right-sided lesions has been the most quoted risk factor for poststroke mania. Indeed, the majority of patients described in case studies and small case series had right-sided lesions. However, this association has been challenged by the description of cases of mania following left hemispheric lesions [31, 36, 42, 57]. Of the 74 cases of mania and stroke, 50 (68 %) had right-sided lesions, while only 11 (15 %) presented left-sided lesions, a difference which reaches statistical significance (Table 4.3).

With respect to stroke location, almost all cases refer to lesions in the right corticolimbic pathways, an integrated system that includes the limbic system and the basal ganglia. The orbitofrontal circuit is a complex functional network that includes the orbitofrontal cortex, the basotemporal region, the thalamus, and the caudate nucleus. This circuit is crucial for mood regulation and social behavior [6, 19, 26]. Basotemporal and orbitofrontal lesions are frequently associated with mood and behavior changes such as disinhibition, lack of spontaneity and affective control, irritability and aggression, decreased social sensitivity, and confabulation. Secondary mania caused by degenerative, infectious, and traumatic disorders was also frequently related with lesions in basal ganglia [6].

Dysregulation at this level results in decreased prefrontal modulation and mood changes expressed as manic symptoms.

Imaging studies and the systematic review of all the cases evidenced that the majority of patients had large middle cerebral artery infarctions, with lesions in the basal ganglia and frontal and temporal lobes [7]. Blumberg et al. found a decreased activation on the right rostral and orbital prefrontal cortex in patients with mania [63].

Cases of mania with left-sided stroke could be explained by a disconnection between left medial and anterior thalamus with the frontal lobe, which could cause a frontal dysfunction. In this situation the frontal lobes induce an inhibitory effect on the limbic system, which ceases to have its modulating role [24].

Mania could also be related with a biochemical dysfunction caused by right hemisphere stroke, which increases the level of brain serotonin. This mechanism seems to occur in mania caused by antidepressant therapy [13, 45]. Mood-stabilizing drugs seem to be effective in the treatment of manic symptoms due to their effect on serotonin system [18].

Establishing the causal relationship between stroke and mania has also been based on other factors than right-sided lesions, namely, a predisposing genetic factor and/or the presence of subcortical brain atrophy. Starkstein et al. found that stroke patients with mania had more subcortical atrophy than the remaining stroke patients matched by lesion size and location [6]. Krauthammer and Klerman excluded patients with previous affective disorder in the diagnosis of secondary mania [5]. In an epidemiological study about geriatric mania, the authors found that the majority of patients did not have personal or family history of affective disorder [64]. However, in our systematic review, we did not find evidence in favor of these two factors. The majority of poststroke mania cases did not have history of family or personal psychiatric disorder or subcortical atrophy (Table 4.3).

The presence of vascular risk factors, such as hypertension and diabetes, is another factor that characterizes late-onset mania [22, 65]. Fujikawa found a significant association between silent cerebral infarcts and mood disorders in elderly [66]. The desirable control of vascular risk factors has impact not only on the prevalence of stroke and other cardiovascular diseases but also on the prevalence of poststroke consequences, such as mania.

Looking at the range and average age of the poststroke mania cases reported in the literature, we observe that the onset of mania occurs much later in life than that what is characteristic of primary mania. The more recent published exception is a case of mania in a 27-year-old female with a right cerebral infarct and heart surgery 1 year and 6 months before, respectively, and without family or personal history of affective disorder [12]. Cassidy and Carroll suggested a cutoff of 47 years old to distinguish between early-onset and late-onset mania [65].

In the systematic review of poststroke mania, we found that the typical patient with mania associated to stroke was a male, without personal/family history of psychiatric disorder, with at least one vascular risk factor, without subcortical atrophy, and with a right cerebral infarct.

Outcome

The follow-up of these patients was described in a minority of cases. Some patients had recurrent episodes of mania or presented hypomania. We could not confirm that about 30 % of patients may develop a bipolar disorder [61].

Management

The mood, cognitive, and behavioral changes that characterize mania can have a strong impact in stroke management and rehabilitation. In this context, the treatment of manic symptoms should be similar to that which is recommended for primary mania. Treatment consists of mood stabilizers and typical or atypical antipsychotics [13, 18, 67, 68]. These drugs should be prescribed to poststroke mania patients with precautions for three main reasons: older patients have a highly sensitivity to psychotropic drugs, the presence of stroke itself could change their efficacy, and stroke patients had frequently other medical comorbidities [68]. Dosages should be lower and increased slower than in primary mania.

Lithium was frequently used with favorable results, but its use is controversial in cases with cerebral lesions because the stroke itself may alter the sensitivity to lithium neurotoxicity [6, 42, 69]. Anticonvulsant mood stabilizers, such as carbamazepine and valproic acid, were effective in other patients, with the advantage of also preventing poststroke seizures [18]. Antipsychotics were used in cases of severe mania with psychotic symptoms, and in recent years atypical antipsychotics have been preferred because they had comparatively less side effects. Antipsychotics are associated with the emergence of extrapyramidal symptoms and parkinsonian syndromes [25]. Other relevant side effects of neuroleptics include drowsiness, increased risk of falls, prolonged QT interval, cardiac arrhythmias including sudden death, increased risk of cardiovascular events including stroke, decreased threshold for seizures, and weight gain. Benzodiazepines were also used as adjunctive treatment for hyperactivity and insomnia [17].

Different neurotransmitters are involved in the orbitofrontal circuit and their excess seems to mediate the relation between and affective disorder. In addition to serotonin, other neurotransmitters could be involved in poststroke mania, what could explain the diversity of therapeutic response to different substances [19].

In systematic review, we have data on the treatment for only 47 (64 %) of the 74 cases included. Mood stabilizers (lithium, carbamazepine, and valproic acid) were used in 62 %, typical antipsychotics (haloperidol) in 32 %, atypical antipsychotics (olanzapine, risperidone) in 19 %, and benzodiazepines (diazepam, lorazepam) in 13 %. We found three cases of stroke patients with depression that developed mania after antidepressant treatment [33, 36, 42]. Data on dosages, duration of the treatment, and efficacy were so scarce that it was impossible to provide any meaningful results.

The lack of placebo-controlled and double-blind trials and the marked differences in efficacy between the same or similar drugs in different cases reinforce doubts about the role of pharmacological treatment in the resolution of symptoms and impede the definition of targeted and evidence-based treatment guidelines [6, 17, 68].

Conclusion

Although rare, mania has high potential disruptive impact after stroke, during the acute care and later, in the post-acute and rehabilitation phase. A manic patient has difficulty in understanding why he is in hospital. He resists treatment and rehabilitation strategies, denying and depreciating the disease symptoms. Manic symptoms could be a part of a clinical profile characterized by other neuropsychiatric changes, such as delirium, denial, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychotic disorders, and personality changes due to stroke. We have carefully examined the patient in order to establish the differential diagnosis with these other conditions, because all of them have common symptoms which may mislead the diagnosis. Only a detailed psychiatric/psychological assessment can detect not only the more frequent neuropsychiatric poststroke changes but other rare consequences, such as mania.

Poststroke mania should also be considered in any manic patient who presents concomitant neurological focal deficits and is older than expected for the onset of primary mania. As stressed above, typically these patients are male, without psychiatric antecedents or subcortical atrophy, with vascular risk factors and right infarct.

Case 1: Mania in the Acute Phase of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

A 65-year-old female, without vascular risk factors and no personal or family history of mood disorders, was admitted because of acute onset of severe headache, vomiting, and brief loss of consciousness. She was alert but somnolent, oriented, and collaborative, with neck stiffness and left hemiparesis (Hunt and Hess’ grade 2). CT scan revealed subarachnoid hemorrhage with hematic densities in the basal cisterns, posterior fossa, third and fourth ventricles, and left lateral ventricle, with moderate hydrocephalus (Fig. 4.1). Angiography revealed an intracranial left vertebral artery dissection.

Psychiatric/psychological assessment was performed on the third day of hospitalization. The patient was oriented, but she presented attention and short-term memory mild defects. In the Mania Rating Scale, she presented an elevated mood, with euphoria, elation, and ecstasy (item 1). This period of intense self-satisfaction and optimism alternates with anger (item 9). She presented a mild overactivity (item 2), a severe increased rate or amount of speech (item 6), and hyper-religiosity (item 8). The patient reported also a decreased need for sleep (item 4) and eating. She admitted a change in his behavior but denied his neurological disease and psychiatric disturbances (item 11), alluding that there was nothing really wrong with her and presenting a carefree, cheerful, and jovial approach to life, with coolness behavior. She scored 12 on Mania Rating Scale. Her behavioral changes were treated with diazepam (5–20 mg). Thirteen days after the first psychiatric assessment, the manic symptoms had regressed, remained only a hyper-religiosity and a decreased need for sleep. The patient was discharge on the 21st day with a modified Rankin Scale score of 1.

Case 2: Bipolar Disorder After Stroke

A 68-year-old male, active University Professor, with diabetes, hypertension, and coronary heart disease suffered a minor left hemispheric deep parietal ischemic stroke (Fig. 4.2). He had anomic aphasia, alexia with agraphia, and a slight distal upper limb paresis. No cardiac cause of embolism was detected, and apart from <50 % ipsilateral carotid stenosis, no other abnormal results were found in a comprehensive workup in search of the cause of his stroke. He recovered completely and returned to his previous academic and social activities. Two months later he had a fist hypomanic episode characterized by multiple and grandiose plans, optimism, and decreased sleep, which was shortly followed by a prolonged major depressive episode, during which the patient had very depressed mood, pessimism, and decreased energy, avoiding social contacts and staying in bed for prolonged periods. Except for what could be judged retrospectively as a hyperthymic temperament, he had no previous psychiatric history. During the next 2 years, he alternated depressive and manic episodes. Although the patient complained mainly of his depressive symptoms, manic episodes were particularly disturbing because of overactivity, engagement in multiple commitments, decreased sleep, and excessive spending including traveling to foreign countries. Depressive episodes were treated with venlafaxine and manic episodes controlled with haloperidol, although the patient frequently missed medical appointments during these periods. The clinical condition was finally stabilized with lithium and lamotrigine.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Mood disorders. In: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed, text revision. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2002. p. 345–428.

Ferro JM, Caeiro L, Santos C. Poststroke emotional and behavior impairment: a narrative review. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27 Suppl 1:197–203.

Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Mood disorders. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. Behavioural sciences/clinical psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. p. 534–72.

Vuilleumier P, Ghika-Schmid F, Bogousslavsky J, Assal G, Regli F. Persistent recurrence of hypomania and prosoaffective agnosia in a patient with right thalamic infarct. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1998;11:40–4.

Krauthammer C, Klerman G. Secondary mania. Manic syndromes associated with antecedent physical illness or drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35:1333–9.

Starkstein SE, Pearlson GD, Boston JD, Robinson RG. Mania after brain injury. A controlled study of causative factors. Arch Neurol. 1987;44:1069–73.

Santos CO, Caeiro L, Ferro JM, Figueira ML. Mania and stroke: a systematic review. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32:11–21.

Starkstein SE, Boston JD, Robinson RG. Mechanisms of mania after brain injury. 12 case reports and review of the literature. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988;176:87–100.

House A, Dennis M, Mogridge L, Warlow C, Hawton K, Jones L. Mood disorders in the year after first stroke. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:83–92.

Burvill PW, Johnson GA, Jamrozik KD, Anderson CS, Stewart-Wynne EG, Chakera TM. Prevalence of depression after stroke: the Perth Community Stroke Study. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166:320–7.

Babinski J. Réflexes de défense. Brain. 1922;45:149–84.

Semiz M, Kavakçı O, Yontar G, Yıldırım O. Case of organic mania associated with stroke and open heart surgery. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;64:587.

Duggal HS, Singh I. New-onset vascular mania in a patient with chronic depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;21:480–2.

López JD, Araúxo A, Páramo M. Late-onset bipolar disorder following right thalamic injury. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2009;37:233–5.

Havle N, Ilnem MC, Yener F, Dayan C. Secondary mania after brain stem infarct. Anadolu Psikiyatri Dergisi. 2009;10:163–4.

Rocha FF, Carneiro JG, Pereira Pde A, Correa H, Teixeira AL. Poststroke manic symptoms: an unusual neuropsychiatric condition. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2008;30:173–4.

Dervaux A, Levasseur M. Risperidone and valproate for mania following stroke. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;20:247.

Rocha FF, Correa H, Teixeira AL. A successful outcome with valproic acid in a case of mania secondary to stroke of the right frontal lobe. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:587–8.

Nagaratnam N, Wong KK, Patel I. Secondary mania of vascular origin in elderly patients: a report of two clinical cases. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2006;43:223–32.

Goyal R, Sameer M, Chandrasekaran R. Mania secondary to right-sided stroke-responsive to olanzapine. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:262–3.

Mimura M, Nakagome K, Hirashima N, et al. Left frontotemporal hyperperfusion in a patient with post-stroke mania. Psychiatry Res. 2005;139:263–7.

Celik Y, Erdogan E, Tuglu C, Utku U. Poststroke mania in late life due to right temporoparietal infarction. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58:446–7.

Huffman J, Stern TA. Acute psychiatric manifestations of stroke: a clinical case conference. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:65–75.

Gafoor R, O’Keane V. Three case reports of secondary mania: evidence supporting a right frontotemporal locus. Eur Psychiatry. 2003;18:32–3.

Colenda CC. Mania in late life. The challenges of treating older adults. Geriatrics. 2002;57(50):53–4.

Benke T, Kurzthaler I, Schmidauer C, Moncayo R, Donnemiller E. Mania caused by a diencephalic lesion. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40:245–52.

Caeiro L, Ferro JM, Albuquerque R, Figueira ML. Mania no AVC agudo. Sinapse. 2002;2:90.

Inzelberg R, Nisipeanu P, Joel D, Sarkantyus M, Carasso RL. Acute mania and hemichorea. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2001;24:300–3.

Franco K, Chughtai H. Steroid-induced mania in poststroke patient involving the right basal ganglion and right frontal region. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:446–7.

Leibson E. Anosognosia and mania associated with right thalamic haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:107–8.

Fenn D, George K. Post-stroke mania late in life involving the left hemisphere. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1999;33:598–600.

De León OA, Furmaga KM, Kaltsounis J. Mirtazapine-induced mania in a case of post-stroke depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;11:115–6.

Börnke C, Postert T, Przuntek H, Büttner T. Acute mania due to a right hemisphere infarction. Eur J Neurol. 1998;5:407–9.

Kumar S, Jacobson RR, Sathananthan K. Seasonal cyclothymia to seasonal bipolar affective disorder: a double switch after stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63:796–7.

Kulisevsky J, Berthier ML. A new case of fluoxetine-induced mania in post-stroke depression. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1997;20:180–1.

Liu CY, Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Yang YY, Liu HC. Bipolar disorder following a stroke involving the left hemisphere. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1996;30:688–91.

Trillet M, Vighetto A, Croisile B, Charles N, Aimard G. Hemiballismus with logorrhea and thymo-affective disinhibition caused by hematoma of the left subthalamic nucleus. Rev Neurol (Paris). 1995;151:416–9.

Kulisevsky J, Avila A, Berthier ML. Bipolar affective disorder and unilateral parkinsonism after a brainstem infarction. Mov Disord. 1995;10:799–802.

Tohen M, Shulman KI, Satlin A. First-episode mania in late life. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:130–2.

Kumar KR, Kuruvilla K. Secondary mania following stroke. Indian J Psychiatry. 1994;36:33.

Berthier ML, Kulisevsky J. Fluoxetine-induced mania in a patient with post-stroke depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:698–9.

Turecki G, Mari Jde J, Del Porto JÁ. Bipolar disorder following a left basal-ganglia stroke. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:690.

Kulisevsky J, Berthier ML, Pujol J. Hemiballismus and secondary mania following a right thalamic infarction. Neurology. 1993;43:1422–4.

Berthier ML. Post-stroke rapid cycling bipolar affective disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;160:283.

Starkstein SE, Fedoroff P, Berthier ML, Robinson RG. Manic-depressive and pure manic states after brain lesions. Biol Psychiatry. 1991;29:149–58.

Blackwell MJ. Rapid-cycling manic-depressive illness following subarachnoid haemorrhage. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:279–80.

Fawcett RG. Cerebral infarct presenting as mania. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52:352–3.

Snowdon J. A retrospective case-note study of bipolar disorder in old age. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:485–90.

Drake ME, Pakalnis A, Phillips B. Secondary mania after ventral pontine infarction. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1990;2:322–5.

Starkstein SE, Mayberg HS, Berthier ML, Fedoroff P, Price TR, Dannals RF, et al. Mania after brain injury: neuroradiological and metabolic findings. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:652–9.

Danel T, Comayras S, Goudemand M, et al. Troubles de l’ humeur et infarcts de l’hémisphère droit. Encéphale. 1989;15:549–53.

Mendez MF, Adams NL, Lewandowski KS. Neurobehavioral changes associated with caudate lesions. Neurology. 1989;39:349–54.

Stone K. Mania in the elderly. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;155:220–4.

Goldschmidt TJ, Burch EA, Gutnisky G. Secondary mania from cerebral embolization with nonfocal neurologic findings. South Med J. 1988;81:1309–11.

Bogousslavsky J, Ferrazzini M, Regli F, Assal G, Tanabe H, Delaloye-Bischof A. Manic delirium and frontal-like syndrome with paramedian infarction of the right thalamus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51:116–9.

Cummings JL, Mendez MF. Secondary mania with focal cerebrovascular lesions. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:1084–7.

Jampala VC, Abrams R. Mania secondary to left and right hemisphere damage. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:1197–9.

Cohen MR, Niska RW. Localized right cerebral hemisphere dysfunction and recurrent mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137:847–8.

Shulman K, Post F. Bipolar affective disorder in old age. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;136:26–32.

Rosenbaum AH, Barry Jr MJ. Positive therapeutic response to lithium in hypomania secondary to organic brain syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1975;132:1072–3.

Robinson RG, Boston JD, Starkstein SE, Price TR. Comparison of mania and depression after brain injury: causal factors. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:172–8.

Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, et al. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–35.

Blumberg HP, Stern E, Ricketts S, Martinez D, de Asis J, White T, et al. Rostral and orbital prefrontal cortex dysfunction in the manic state of bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1986–8.

McDonald WM. Epidemiology, etiology, and treatment of geriatric mania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61 Suppl 13:3–11.

Cassidy F, Carroll BJ. Vascular risk factors in late onset mania. Psychol Med. 2002;32:359–62.

Fujikawa T, Yamawaki S, Touhouda Y. Silent cerebral infarctions in patients with late-onset mania. Stroke. 1995;26:946–9.

Robinson RG. Neuropsychiatric consequences of stroke. Annu Rev Med. 1997;48:217–29.

Wijeratne C, Malhi GS. Vascular mania: an old concept in danger of sclerosing? A clinical overview. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2007;116 Suppl 434:35–40.

Evans DL, Byerly MJ, Greer RA. Secondary mania: diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56 Suppl 3:31–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer-Verlag London

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Santos, C.O., Caeiro, L., Ferro, J.M. (2013). Mania. In: Ferro, J. (eds) Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Cerebrovascular Diseases. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Neurological Disease. Springer, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-2428-3_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-2428-3_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-4471-2427-6

Online ISBN: 978-1-4471-2428-3

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)