Abstract

This review is an attempt to provide a comprehensive view of post-traumatic-stress disorder (PTSD) and its therapy, focusing on the use of meditation interventions. PTSD is a multimodal psycho-physiological-behavioral disorder, which calls for the potential usefulness of spiritual therapy. Recent times witness a substantial scientific interest in an alternative mind-to-body psychobehavioral therapy; the exemplary of which is meditation. Meditation is a form of mental exercise that has an extensive, albeit still mostly empiric, therapeutic value. Meditation steadily gains an increasing popularity as a psychobehavioral adjunct to therapy in many areas of medicine and psychology. While the review does not provide a final or conclusive answer on the use of meditation in PTSD treatment we believe the available empirical evidence demonstrates that meditation is associated with overall reduction in PTSD symptoms, and it improves mental and somatic quality of life of PTSD patients. Therefore, studies give a clear cue for a trial of meditation-associated techniques as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy or standalone treatment in otherwise resistant cases of the disease.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

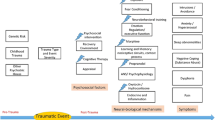

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a clinical syndrome that may develop following extreme traumatic stress. It is an important, albeit relatively uncommon, consequence of exposure to traumatic events, presumably the result of life threats and conditioned fear (Greenberg et al. 2015; Ramage et al. 2016). PTSD is recently defined by four categories of socio-psychological symptoms (DSM-V 2013): (1) intrusion that encompasses re-experiencing the traumatic event through intrusive memories, flashbacks, nightmares, and physiological responses similar to those when the traumatic event occurred; (2) avoidance that encompasses mind-numbing occurrences, such as avoiding situations and people reminding of past trauma, amnesia for trauma-related information, loss of interest in activities, social and emotional detachment, emotional numbing especially for feelings associated with intimacy, and nihilistic feelings of the future; (3) changes in arousal manifested by angry outbursts, sleep problems, startle responses, and hypervigilance; and (4) mood and cognition disorders consisting of difficulty to cope by feeling down and hopeless, dysphoric mood, problems with judgment, reasoning, and emotion perception, as well as with focusing attention on a task completion.

PTSD is a global health issue (Jindani et al. 2015; Ramchand et al. 2015). The disorder develops in approximately 20% of people exposed to a traumatic event (Freedman et al. 2015). It is more prevalent in females than males: typically about twice the rate (Jaycox et al. 2004; Kessler et al. 1995). It affects about 8% of the general US population at some point during their lifetime (Gates et al. 2012). Risk factors for PTSD in adults vary across studies. The three factors identified as having relatively uniform effects are the following: (1) preexisting psychiatric disorders; (2) family history of such disorders; and (3) childhood trauma (Breslau 2002). The lifetime prevalence in the US female population is more than 10% (Kessler et al. 1995). The prevalence rate of lifetime PTSD in Canada is estimated at 9.2%, with a rate of current (one-month) PTSD of 2.4% (Van Ameringen et al. 2008). According to the 2013 Canadian Forces Mental Health Survey, 5.3% of soldiers report experiencing PTSD at some point of service (Zamorski et al. 2016). PTSD is alleged to be associated with high rates of concurrent psychiatric disorders, particularly including, but not limited to, substance and alcohol/nicotine addictions and all kinds of depressive disorders (Williamson et al. 2017; Bollinger et al. 2000; Keane and Wolfe 1990). Further, traumatic events triple the risk of developing subsequent psychotic experiences later in life; the effect persist after adjustment for the possible presence of a mental disorder preceding the psychotic post-traumatic episode, which points to a direct and strong association between PTSD and psychosis (McGrath et al. 2017).

Aside from the socio-psychological or psychiatric consequences, PTSD may also encompass debilitating somatic disorders. In this context, comorbid metabolic and hormonal sequelae are notably underscored (Morris et al. 2012). PTSD increases two-fold the risk to develop insulin-resistant diabetes type 2, and also is conducive to the development of obesity, and other atherosclerosis-related pathological conditions (Roberts et al. 2015). Although molecular phenomena linking such comorbid conditions to PTSD remain mostly conjectural, interestingly the common denominator seems to be a proinflammatory propensity endowed by PTSD (von Känel et al. 2007). Since somatic complications of PTSD may come to light in a variably and unpredictably delayed time scale, patients with the pathologies above outlined ought to be assiduously scrutinized in the process of anamnesis taking for the past history of a traumatic imbroglio to identify the biopsychosocial disease links.

PTSD has complex and multiple symptoms and is a highly impairing condition that imposes a significant economic and social burden (Hawkins et al. 2015; Kessler 2000). When coping with serious illness, choosing the right therapy is of key importance. However, treating patients suffering from PTSD poses a significant challenge and therapy still remains within the arcana of medical art. The existing guidelines for pharmacotherapy concern so broad and divergent groups of drugs, for instance, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) like fluoxetine and related compounds, monoamine oxidase inhibitors like phenelzine, tetracyclic antidepressants like mitrazepin, antipsychotics like risperidone, and the list goes on (Cipriani et al. 2017). Pharmacotherapy should be individually tailored, taking into account the background history and current disease manifestations, with the placebo effect being sometimes the best therapeutic solution.

2 Meditation Interventions in Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Since the available evidence is not robust enough to suggest any pharmacotherapy of PTSD of finite efficacy, psychotherapeutic interventions have come to the fore as a prioritized option (Bisson and Andrew 2007; Schäfer and Najavits 2007). A variety of psychotherapy treatments have been developed for PTSD, such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy, stress management, or eye movement desensitization and reprocessing; the therapies that also include cognitive group treatment. Among the psychological interventions, meditation has been recognized as one of the notably effective modes. Meditation is an empirically-validated treatment for PTSD. A growing body of evidence suggests that meditation-based interventions have the potential to reduce symptoms and improve mood and general well-being (Mitchell et al. 2014; Seppälä et al. 2014). Further, meditation enhances openness to experience, one of the personality traits, which is associated with improvement in coping with stress by decreasing avoidance-oriented attitude to stressful situations and with better control of one’s emotions (Pokorski and Suchorzynska 2018).

Meditation is a mind-to-body practice. It is an essential element in all of the world’s major contemplative, spiritual, and philosophical traditions (Walsh 1999; Shapiro et al. 2008). According to Manocha (2000) meditation is a discrete and well-defined experience of a state of ‘thoughtless awareness’ or mental silence, in which the activity of the mind is minimized without reducing the level of alertness. Walsh and Shapiro (2006) described meditation as the self-regulation practices that aim to bring mental processes under voluntary control through focusing attention and awareness. The effects of meditation on health are based on the principle of mind-to-body connection and there is a growing body of literature showing the efficacy of meditation in various health related problems (Hussain and Bhushan 2010). Mind-to-body practices are increasingly used in the treatment of PTSD and are associated with a positive influence on the stress-induced illnesses such as depression and PTSD in most existing studies (Kim et al. 2013). As described by Cloitre et al. (2011) meditation has been identified as an effective second-line approach for emotional, attentional, and behavioral (e.g., aggression) disturbances in PTSD. Lang et al. (2012) further suggest the meditation as a therapeutic intervention for PTSD.

Anapanasati meditation, which is a concentrative meditation that focuses on one’s respiration and suppresses other thoughts, is a tool for exploring subtle awareness of mind and life. Mindfulness of breathing helps oxygenate the body, reduces stress and anxiety, and induces peace of mind (Deo et al. 2015). The meditator is able to focus attention and see the impermanence of his experiences, which nullifies the feeling of being destroyed by them. Breathing interventions boost emotion regulatory processes in healthy populations (Arch and Craske 2006). Sack et al. (2004) have indicated that breathing-based meditation practices may be beneficial for PTSD. Seppälä et al. (2014) have reported that breathing-based meditation decreases posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in US military veterans.

Mindfulness meditation, which is a sensitive non-concentrative type of meditation that notices things and picks up the object of attention as it pleases, helps reduce the level of stress in PTSD patients by cultivating awareness and acceptance of dysfunctional mental behaviors and helping change emotional experiences (Steinberg and Eisner 2015). The term ‘mindfulness’ has been used to refer to a psychological state of awareness, a practice that promotes this awareness, a mode of processing information, and a characterological trait. Germer et al. (2005) defines mindfulness as moment-by-moment awareness. The evidence concurs that mindfulness helps develop effective emotion regulation in the brain (Davis and Hayes 2011; Siegel 2007). Mindfulness is associated with low levels of neuroticism, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, as well as high levels of self-esteem and satisfaction with life (Tanner et al. 2009; Brown and Ryan 2003). Mindfulness meditation is indicated in PTSD as it leads to positive outcomes in trauma survivors (Christelle et al. 2014; Follett et al. 2006).

Likewise, Vedananupassana meditation or awareness of sensations and feelings is a form of mindfulness meditation which is useful in the treatment of PTSD. Chronic pain and PTSD commonly co-occur in the aftermath of a traumatic event (Palyo and Beck 2005). In addition, both are mutually maintaining conditions, and pain sensations can trigger PTSD symptoms (Sharp and Harvey 2001). People with chronic pain and co-morbid PTSD report poorer quality of life (Morasco et al. 2013). Vedananupassana meditation is beneficial in alleviating pain in the individuals with PTSD.

Loving-kindness meditation is a practice designed to enhance feelings of kindness and compassion for self and others. Self-compassion is considered a promising change mode of behavioral approach in the treatment of PTSD (Hoffart et al. 2015). Kearney et al. (2014) have conducted a loving-kindness meditation study in 42 military veterans with active PTSD and found the effect of increased positive emotions. According to Kearney et al. (2013), this kind of meditation appears safe and acceptable, and is associated with reduced symptoms of PTSD and depression. Hinton et al. (2013) have demonstrated that loving-kindness meditation has a potential to increase emotional flexibility and to decrease rumination. It may regulate emotional stability and form a new adaptive processing mode centered on psychological flexibility.

Research has shown that transcendental meditation can also be an effective technique to treat PTSD. Transcendental meditation is derived from the ancient yoga teaching (Lansky and St. Louis 2006). It is a purely mental technique that falls within the category of ‘automatic self-transcending’ because the practice allows the mind to effortlessly settle inward, beyond thought, to experience the source of thought, pure awareness (Rees 2011; Travis and Shear 2010). Chhatre et al. (2013) have described transcendental meditation as a behavioral stress reduction program that incorporates mind-to-body approach, and demonstrated its effectiveness in improving outcomes through stress reduction. Rees et al. (2013) have shown a reduction in posttraumatic stress symptoms in Congolese refugees practicing transcendental meditation. Rosenthal et al. (2011) have highlighted the successful use of transcendental meditation on the veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom suffering from PTSD. Further, Orme-Johnson and Barnes (2014) have explored a reduction in anxiety in response to transcendental meditation.

The therapeutic added value of meditation may be its hypnotic-like effect. Zazen, ‘seated meditation’ in which the body and mind are calmed, has an apparent hypnotic influence as evidenced by blocking the cortical alpha wave EGG response to repeated click stimuli (Kasamatsu and Tomio 1966). Hypnogenic engagement of attention with imaginary resources prevents the perception of the sense of reality and hinders the passage of external painful remembrances (Tellegen and Atkinson 1974), with understandably beneficial effects in PTSD. Hypnotherapy alone has a beneficial effect on PTSD symptoms. The largest to-date meta-analysis on the subject, performed on the selected 6 studies covering 391 subjects, has demonstrated positive effects of hypnotherapeutic techniques specifically related to avoidance and intrusion, and to overall PTSD symptomatology (O’Toole et al. 2016). Meditation-associated hypnosis, although seldom by far considered for PTSD treatment, appears to be of distinct efficacy (Lesmana et al. 2009).

3 Conclusions

PTSD is a psycho-physiologic-behavioral disorder, which calls for psychobehavioral ways of treatment. Meditation is an important part of health and spiritual practice. It is a form of mental exercise that has an extensive therapeutic value. There are three major types of meditative practices: mindfulness of breathing, non-concentrative mindfulness, and transcendental meditation. Due to a multitude of meditative techniques and approaches, it is hard to average meditations together to define the underlying mechanisms and clinical benefits. The difficulty consists in the paucity of verifiable research, small sample sizes of patients, variable methods of meditation, setting different outcome measures, and other issues. Despite these shortcomings, empirical evidence accumulates to demonstrate that meditation is associated with overall reduction in PTSD symptoms, and it improves mental and somatic quality of life of PTSD patients. Meditation interventions seem justifiable as an adjunct to the ill-defined polypharmacy arsenal in PTSD treatment or a standalone trial in otherwise failed treatment efforts of this multimodal disease.

References

Arch JJ, Craske MG (2006) Mechanisms of mindfulness: emotion regulation following a focused breathing induction. Behav Res Ther 44:1849–1858

Bisson J, Andrew M (2007) Psychological treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD003388

Bollinger AR, Riggs DS, Blake BDD, Ruzek JI (2000) Prevalence of personality disorders among combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress 13(2):255–270

Breslau N (2002) Epidemiologic studies of trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and other psychiatric disorders. Can J Psychiatr 47(10):923–929

Brown KW, Ryan RM (2003) The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 84(4):822–848

Chhatre S, Metzger DS, Frank I, Boyer J, Thompson E, Nidich S, Montaner LJ, Jayadevappa R (2013) Effects of behavioral stress reduction transcendental meditation intervention in persons with HIV. AIDS Care 25(10):1291–1297

Christelle AI, Ngnoumen T, Langer EJ (2014) Mindfulness meditation for posttraumatic stress disorder. Wiley

Cipriani A, Williams T, Nikolakopoulou A, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Ipser J, Cowen PJ, Geddes JR, Stein DJ (2017) Comparative efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: a network meta-analysis. Psychol Med 19:1–10

Cloitre M, Courtois CA, Charuvastra A, Carapezza R, Stolbach BC, Green BL (2011) Treatment of complex PTSD: results of the ISTSS expert clinician survey on best practices. J Trauma Stress 24(6):615–627

Davis DM, Hayes JA (2011) What are the benefits of mindfulness? A practice review of psychotherapy-related research. Psychotherapy (Chic) 48(2):198–208

Deo G, Itagi RK, Thaiyar MS, Kuldeep KK (2015) Effect of anapanasati meditation technique through electrophotonic imaging parameters: a pilot study. Int J Yoga 8(2):117–121

DMS-5 (2013) American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8

Follett V, Palm KM, Pearson AN (2006) Mindfulness and trauma implications for treatment. J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther 24(1):45–61

Freedman SA, Dayan E, Kimelman YB, Weissman H, Eitan R (2015) Early intervention for preventing posttraumatic stress disorder: an Internet-based virtual reality treatment. Eur J Psychotraumatol 6:25608

Gates MA, Holowka DW, Vasterling JJ, Keane TM, Marx BP, Rosen RC (2012) Posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans and military personnel: epidemiology, screening, and case recognition. Psychol Serv 9(4):361–382

Germer CK, Siegel RD, Fulton PR (2005) Mindfulness and psychotherapy. Guilford Press, New York

Greenberg N, Brooks S, Dunn R (2015) Latest developments in post-traumatic stress disorder: diagnosis and treatment. Br Med Bull 114(1):147–155

Hawkins EJ, Malte CA, Grossbard JR, Saxon AJ (2015) prevalence and trends of concurrent opioid analgesic and benzodiazepine use among veterans affairs patients with post-traumatic stress disorder, 2003–2011. Pain Med 16(10):1943–1954

Hinton DE, Ojserkis RA, Jalal B, Peou S, Hofmann SG (2013) Loving-kindness in the treatment of traumatized refugees and minority groups: a typology of mindfulness and the nodal network model of affect and affect regulation. J Clin Psychol 69(8):817–828

Hoffart A, Øktedalen T, Langkaas TF (2015) Self-compassion influences PTSD symptoms in the process of change in trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapies: a study of within-person processes. Front Psychol 6:1273

Hussain D, Bhushan B (2010) Psychology of meditation and health: present status and future directions. Int J Psychol Psychol Ther 10(3):439–451

Jaycox LH, Ebener P, Damesek L, Becker K (2004) Trauma exposure and retention in adolescent substance abuse treatment. J Trauma Stress 17:113–121

Jindani F, Turner N, Khalsa SB (2015) A yoga intervention for posttraumatic stress: a preliminary randomized control trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015:351746

Kasamatsu A, Tomio T (1966) An electroencephalographic study on the Zen meditation (Zazen). Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 20(4):315–336

Keane TM, Wolfe J (1990) Comorbidity in post-traumatic stress disorder: an analysis of community and clinical studies. J Appl Soc Psychol 20:1776–1788

Kearney DJ, Malte CA, McManus C, Martinez ME, Felleman B, Simpson TL (2013) Loving-kindness meditation for posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot study. J Trauma Stress 26(4):426–434

Kearney DJ, McManus C, Malte CA, Martinez ME, Felleman B, Simpson TL (2014) Loving-kindness meditation and the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Med Care 52(12 Suppl 5):S32–S38

Kessler RC (2000) Posttraumatic stress disorder: the burden to the individual and to society. J Clin Psychiatry 61(Suppl 5):4–12

Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB (1995) Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatr 52(12):1048–1060

Kim SH, Schneider SM, Kravitz L, Mermier C, Burge MR (2013) Mind-body practices for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Investig Med 61(5):827–834

Lang AJ, Strauss JL, Bomyea J, Bormann JE, Hickman SD, Good RC, Essex M (2012) The theoretical and empirical basis for meditation as an intervention for PTSD. Behav Modif 36(6):759–786

Lansky EP, St Louis EK (2006) Transcendental meditation: a double-edged sword in epilepsy? Epilepsy Behav 9(3):394–400

Lesmana CB, Suryani LK, Jensen GD, Tiliopoulos N (2009) A spiritual-hypnosis assisted treatment of children with PTSD after the 2002 Bali terrorist attack. Am J Clin Hypn 52(1):23–34

Manocha R (2000) Why meditation. Aust Fam Physician 29(12):1135–1138

McGrath JJ, Saha S, Lim CCW et al (2017) Trauma and psychotic experiences: transnational data from the World Mental Health Survey. Br J Psychiatry 211(6):373–380

Mitchell KS, Dick AM, DiMartino DM, Smith BN, Niles B, Koenen KC, Street A (2014) A pilot study of a randomized controlled trial of yoga as an intervention for PTSD symptoms in women. J Trauma Stress 27:121–128

Morasco BJ, Lovejoy TI, Lu M, Turk DC, Lewis L, Dobscha SK (2013) The relationship between PTSD and chronic pain: mediating role of coping strategies and depression. Pain 154(4):609–616

Morris MC, Compas BE, Garber J (2012) Relations among posttraumatic stress disorder, comorbid major depression, and HPA function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 32(4):301–315

Orme-Johnson DW, Barnes VA (2014) Effects of the transcendental meditation technique on trait anxiety: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Altern Complement Med 20(5):330–341

O’Toole SK, Solomon SL, Bergdahl SA (2016) A meta-analysis of hypnotherapeutic techniques in the treatment of PTSD symptoms. J Trauma Stress 29(1):97–100

Palyo SA, Beck JG (2005) Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, pain, and perceived life control: associations with psychosocial and physical functioning. Pain 117(1–2):121–127

Pokorski M, Suchorzynska A (2018) Psychobehavioral effects of meditation. Adv Exp Med Biol 1023:85–91

Ramage AE, Litz BT, Resick PA, Woolsey MD, Dondanville KA, Young-McCaughan S, Borah AM, Borah EV, Peterson AL, Fox PT, STRONG STAR Consortium (2016) Regional cerebral glucose metabolism differentiates danger- and non-danger-based traumas in post-traumatic stress disorder. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 11(2):234–242

Ramchand R, Rudavsky R, Grant S, Tanielian T, Jaycox L (2015) Prevalence of, risk factors for, and consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems in military populations deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Curr Psychiatr Rep 17(5):37

Rees B (2011) Overview of outcome data of potential meditation training for soldier resilience. Mil Med 176(11):1232–1242

Rees B, Travis F, Shapiro D, Chant R (2013) Reduction in posttraumatic stress symptoms in Congolese refugees practicing transcendental meditation. J Trauma Stress 26(2):295–298

Roberts AL, Agnew-Blais JC, Spiegelman D, Kubzansky LD, Mason SM, Galea S, Hu FB, Rich-Edwards JW, Koenen KC (2015) Posttraumatic stress disorder and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in a sample of women: a 22-year longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiat 72(3):203–210

Rosenthal JZ, Grosswald S, Ross R, Rosenthal N (2011) Effects of transcendental meditation in veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom with posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot study. Mil Med 176(6):626–630

Sack M, Hopper JW, Lamprecht F (2004) Low respiratory sinus arrhythmia and prolonged psychophysiological arousal in posttraumatic stress disorder: heart rate dynamics and individual differences in arousal regulation. Biol Psychiatry 55:284–290

Schäfer I, Najavits LM (2007) Clinical challenges in the treatment of patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and substance abuse. Curr Opin Psychiatr 20(6):614–618

Seppälä EM, Nitschke JB, Tudorascu DL, Hayes A, Goldstein MR, Nguyen DT, Perlman D, Davidson RJ (2014) Breathing-based meditation decreases posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in U.S. military veterans: a randomized controlled longitudinal study. J Trauma Stress 27(4):397–405

Sharp TJ, Harvey AG (2001) Chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder: mutual maintenance? Clin Psychol Rev 21(6):857–877

Shapiro SL, Oman D, Thoresen CE, Plante TG, Flinders T (2008) Cultivating mindfulness: effects on well-being. J Clin Psychol 64(7):840–862

Siegel DJ (2007) The mindful brain: reflection and attunement in the cultivation of well-being. Norton & Company, New York

Steinberg CA, Eisner DA (2015) Mindfulness-based intervention for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Int J Behav Consult Ther 9(4):11–17

Tanner MA, Travis F, Gaylord-King C, Haaga DA, Grosswald S, Schneider RH (2009) The effects of the transcendental meditation program on mindfulness. J Clin Psychol 65(6):574–589

Tellegen A, Atkinson G (1974) Openness to absorbing and self-altering experiences (‘absorption’), a trait related to hypnotic susceptibility. J Abnorm Psychol 83:268–277

Travis F, Shear J (2010) Focused attention, open monitoring and automatic self-transcending: categories to organize meditations from Vedic, Buddhist and Chinese traditions. Conscious Cogn 19(4):1110–1118

Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Patterson B, Boyle MH (2008) Post-traumatic stress disorder in Canada. CNS Neurosci Ther 14(3):171–181

von Känel R, Hepp U, Kraemer B, Traber R, Keel M, Mica L, Schnyder U (2007) Evidence for low-grade systemic proinflammatory activity in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Res 41(9):744–752

Walsh R (1999) Essential spirituality: the seven central practices. Wiley, New York

Walsh R, Shapiro SL (2006) The meeting of meditative disciplines and Western psychology: a mutually enriching dialogue. Am Psychol 61:227–239

Williamson V, Stevelink SAM, Greenberg K, Greenberg N (2017) prevalence of mental health disorders in elderly U.S. military veterans: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2017.11.001

Zamorski MA, Bennett RE, Boulos D, Garber BG, Jetly R, Sareen J (2016) The 2013 Canadian forces mental health survey. Can J Psychiatr 61(1 Suppl):10S–25S

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to Rev. Harispaththuwe Ariyawansalankara Thero from Vipassana Meditation Center in Colombo, Sri Lanka; Dr. David R. Leffler, Executive Director of the Center for Advanced Military Science (CAMS) Institute of Science, Technology and Public Policy, Iowa; and Dr. Fred Travis, a post-doc fellow in basic sleep research at the University of California, Davis, CA.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Jayatunge, R.M., Pokorski, M. (2018). Post-traumatic Stress Disorder: A Review of Therapeutic Role of Meditation Interventions. In: Pokorski, M. (eds) Respiratory Ailments in Context. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology(), vol 1113. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/5584_2018_167

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/5584_2018_167

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-04024-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-04025-3

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)