Abstract

E-patients ‘empowered’ by Web information are much more likely to participate in health care decision processes and take responsibility for their own health. The purpose of the study was to determine the influence of Internet use and online health information on the attitude, behavior, and emotions of Polish citizens aged 50+, with special regard to their attitude towards health professionals and the health care system. A total of 323 citizens, aged 50 years and above, who used the Internet for health purposes, were selected from the Polish population by random sampling. The sample collection was carried out by Polish opinion poll agencies in 2005, 2007, and 2012. The Internet was used by 27.8 % of Polish citizens aged 50+ for health purposes in the years 2005–2012. 69.7 % of respondents were looking for health information that might help them to deal with a consultation, 53.9 % turned to the Internet to prepare for a medical appointment, and 63.5 % to assess the outcome of a medical consultation and obtain a ‘second opinion’. The most likely effects of health related use of the Internet were: willingness to change diet or other life-style habits (48.0 % of respondents) and making suggestions or queries on diagnosis or treatment by the doctor (46.1 %). Feelings of reassurance or relief after obtaining information on health or illness were reported by a similar number of respondents as feelings of anxiety and fear (31.0 % and 31.3 % respectively). Online health information can affect the attitudes, emotions, and health behaviors of Polish citizens aged 50+ in different ways.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The world population is rapidly aging, which implies a significant increase in the demand for health care and social services. At the same time, the fast development of information and communication technologies (ICT) is being observed. The increasing relevance of the Internet is undeniable, and the use of Web-derived health information is rapidly growing (Pew Internet 2014; Seybert 2012; van Uden-Kran et al. 2009; Kummervold et al. 2008; Andreassen et al. 2007; Krane Harris Poll 2006). In many countries, the increase in the number of Internet health users is relatively larger than the increase due to the number of Internet users, and cannot be explained only by reference to improved Internet access (Pew Internet 2014; Kummervold et al. 2008; Krane Harris Poll 2006). Moreover, there has been a strong growth in e-health usage by the elderly (Pew Internet 2014; Ressi 2011; Kaiser Foundation 2004; Ferguson 2000) and their use of online health services is increasing faster than any other group (Wald et al. 2007; Campbell and Nolfi 2005; Ferguson 2000).

New e-health technologies empower citizens to exhibit behavior more challenging to the traditional passive model of doctor-patient relationship (Wald et al. 2007; Akerkar and Bichile 2004; Ferguson 2004). ICT tools provide opportunities for such patients, so-called ‘e-patients’, who see themselves as equal partners with their doctors in the healthcare process (Ressi 2011; Grant 2010; Hoch and Ferguson 2005). E-patients actively gather information about medical conditions using electronic communication tools to achieve full participation in health care decision-making processes (Ressi 2011; Grant 2010).

Health professionals and researchers no longer control the production and dissemination of medical information, and citizens have become co-producers of health information that is spread via different websites, emails, and virtual communities (Santana et al. 2011; van Uden-Kraan et al. 2009). Doctor-patient interaction often becomes influenced by what patients have learned via the Web. Physicians more often meet patients who expect their doctors to interpret their Internet-acquired information (Wald et al. 2007; Ziebland et al. 2004). Better informed and knowledgeable patients may be better prepared and more likely to ask doctors relevant and critical questions as a result of researching online health information (Santana et al. 2011; Ziebland et al. 2004). Therefore, the way in which online health information is presented and discussed during medical consultation can affect not only the course of the doctor-patient relationship, but also clinical outcomes (Wald et al. 2007; Bylund et al. 2007). A study performed among British primary care doctors has revealed that 75 % of physicians had patients who presented information retrieved from the Web at some point in time (Malone et al. 2004) and a Harris Poll showed that 52 % of adults who obtained health information online reported discussing this information with their doctor at least once (Krane Harris Poll 2006). Furthermore, ‘the Cybercitizen Survey’ conducted in the U.S. has shown that among 99 million ‘empowered’ American adults the Internet was used more frequently than a doctor (61.1 %), information found online at appointment was discussed with health professionals (54.7 %) and health decisions were changed based on information obtained online (45.8 %) (Ressi 2011). General practitioners report that the length of consultation has increased due to patient questions related to the information found on the Internet, and the expectations of patients who have consulted Internet medical information are higher and sometimes unrealistic (Santana et al. 2011; McCaw et al. 2007; Murray et al. 2003).

Further research is needed to investigate the precise nature of the influence of medical information obtained from the Internet on patients’ behavior and decision-making processes. Hence, the aim of the study was to determine the influence of Internet use and online health information on the attitude, behavior, and emotions of Polish citizens aged 50+, with special regard to their attitude towards health professionals and the health care system.

2 Methods

Respondents were provided with comprehensive information concerning the objectives and scope of the survey and gave their informed consent. The survey protocol was approved by the Bioethical Committee at Wroclaw Medical University, Poland (statutory activity 481/2010).

A total of 1,162 citizens aged 50 years and more were selected from the Polish population by random sampling. Data was obtained from a subsample of adults 50+ in three subsequent surveys of Internet use in Poland in 2005 (n = 366), 2007 (n = 368), and 2012 (n = 428), conducted among adults of all age categories (n = 3,027). The sample collection was carried out by the Polish opinion poll agencies (CBOS, TNS), using computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) in November 2005, April 2007, and October–November 2012 subsequently. Random digital dialing in strata was used to ensure a randomized representative sample of the population. Quotas were constructed, based on census data for age, gender, and place of residence (size of the place of residence and region of the country) to make sure the data was representative in this regard. Both landline telephones and mobile phones were included in the survey. The poll agencies conducting the interview were instructed to follow standard procedures related to contact with a replacement if a person originally selected for interview was unavailable (i.e. because of incorrect phone number, not answering the phone, not at home, or unwilling to participate). No variables had more than 5 % missing data. Finally, among a sample of citizens 50+, a subgroup of 323 persons was chosen from respondents who answered positively to the question concerning use of Internet for health related purposes.

The questionnaire used in the study (the same in all three surveys) was designed for CATI. The subjects were asked to respond to questions investigating different aspects of use of the Internet for health purposes and consequences of its use. The frequency of some aspects of Internet use to better handle medical consultations was assessed by Set A of questions: Do you use the Internet to: (1) find health information that can help you decide whether to consult a health professional? (2) find health information prior to an appointment? (3) find information after an appointment with health professionals (e.g. for second opinion)? The response categories were “Always”, “Often”, “Sometimes”, “Rarely”, and “Never”. For transparency of analysis, the initial five options were grouped into three categories: “Always or often”, “Sometimes or rarely”, and “Never”. Different emotions triggered by using the Internet and researching online health information were measured by Set B of questions: (1) Do you worry about confidentiality related to use of the Internet? (2) Has the information on health or illness which you have obtained from the Internet led to feelings of anxiety? (3) Has the information on health or illness which you have obtained from the Internet led to feelings of reassurance or relief? The response categories were “Yes”, “No”, and “Do not know”. For clarity of analysis, the responses “No” and “Do not know” were grouped into one category: “No/Undecided”. The influence of online health information on citizens’ attitudes and behaviors towards health professionals and health systems was assessed by Set C of questions: Has the information on health or illness which you have obtained from the Internet led to any of the following: (1) Willingness to change diet or other life style habits? (2) Suggestions or queries on diagnosis or treatment to your family doctor, specialist or other health professional? (3) Changing the use of medicine without consulting your family doctor, specialist or other health professional? (4) Making, cancelling or changing an appointment with your family doctor, specialist or other health professional? The response categories were “Yes”, “No” and “Do not know”. The responses “No” and “Do not know” were grouped into one category: “No/Undecided”. The questionnaire also contained items related to socio-demographic characteristics and health conditions (e.g. the age, gender, education, place of residence, Internet and mobile phone use, and chronic diseases of the respondent).

2.1 Statistical Analysis

Variables were compared in terms of their average scores to identify significant predictors. The type of distribution for all variables was determined. Two quantitative variables (age and numbers of doctor’s visits during the previous 12 months) had no normal distribution, which was verified with the Shapiro-Wilk test of normality. Arithmetic mean, standard deviations, median, as well as the range of variability (extremes) were calculated for measurable (quantitative) variables, whereas for qualitative variables, a frequency (percentage) with a 95 % confidence interval was determined. A nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test was conducted to compare the distribution of quantitative variables between groups studied (equivalent to the Mann-Whitney U test). For qualitative variables, Fisher’s exact test for contingency tables, or the chi-squared test (when the computational complexity did not allow for the implementation of Fisher’s exact test) were used to determine statistically significant dependencies. All tests were two-sided, and the significance level was set at 0.05. A statistical analysis was carried out with R version 3.0.2 (for Mac OS X 10.9.4) software.

Analyses were made within the total sample, in the subsamples of younger and older respondents, and subsamples of three subsequent surveys from 2005, 2007, and 2012. Studies of the total sample enabled the results for the population to be generalized, whereas study of the subsamples led to a better understanding of changes over time and factors affecting the attitudes and behaviors of the respondents.

3 Results

3.1 Characteristics of Respondents

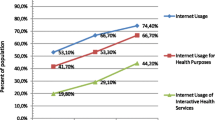

Among a total of 1,162 citizens aged 50 years and over, 27.8 % of Polish citizens 50+ (n = 323) used the Internet for health related purposes, and were included into the study. The study group consisted of 164 males (50.8 %) and 159 females (49.2 %), and the median age was 56 (min-max: 50–83). Two age categories were taken into consideration: 50–59 years of age (n = 217) and 60 years of age and over (n = 106). Three subgroups corresponding to each of the surveys have also been highlighted: Internet users for health purposes (IUHP) 2005 (n = 56), IUHP 2007 (n = 96), and IUHP 2012 (n = 171). With respect to location, 34.8 % of total respondents (n = 112) lived in cities (over 100,000 residents), 34.9 % (n = 113) in towns, and 30.4 % in rural areas (n = 98). As far as employment status is concerned, 43.8 % (n = 141) of older citizens still had paid work, whereas 5.9 % (n = 19) were permanently sick or disabled. The median number of doctor’s visits during the previous 12 months was 4 (min-max: 0–99); and more than 90 % of citizens 50+ assessed their health as at least ‘fair’. Further information on the study population is provided in Table 1.

3.2 Internet Use to Better Handle the Medical Consultation

70.3 % of citizens aged 50 and over were looking for health information that might help them take a decision as to whether to consult a health professional; 54.5 % turned to the Internet to find medical information prior to an appointment, and 63.8 % were looking for health information to assess the outcome of the medical consultation and get a ‘second opinion’. The younger group of respondents (50–59) had a rather more proactive stance, and used the Internet for these purposes slightly more often when compared with older respondents (60+). However, this trend has statistical significance only in the case of searching for online health information prior to an appointment (p = 0.017). Analyzing subsequent surveys, citizens 50+ in 2012 used the Internet significantly more often than in 2005 and 2007: to find health information that could help them make a decision about consulting a health professional (p = 0.030), to be prepared for a medical consultation (p = 0.035) and to assess the outcome of the consultation with the doctor (p = 0.008) (Table 2).

3.3 The Influence of Online Health Information on the Attitudes and Behavior of Citizens 50+

Willingness to change diet or other life-style habits (48.0 % of positive answers), or making suggestions or queries on diagnosis or treatment to the doctor (46.1 %), were the most likely effects of health-related use of the Internet. Feelings of reassurance or relief after obtaining information on health or illness were reported by a similar number of respondents as feelings of anxiety and fear (31.0 % and 31.3 %, respectively). On the other hand, online health information caused 20.4 % of citizens aged 50 and over to make, change or cancel an appointment with a doctor, and 7.7 % of respondents took a critical decision to change their use of medicines without consulting their family doctor, specialist or any other health professionals. Concerns about confidentiality of transmitted data were expressed by 7.4 % of older citizens (Table 3).

Comparative analysis showed that the older group of respondents (60+) had significantly more concerns about the lack of confidentiality of contact via the Internet (4.9 % in IUHP 50–59 vs. 12.5 % in IUHP 60+, p = 0.030). At the same time, they felt anxiety caused by information obtained from the Internet significantly less often than the younger group of citizens (35.0 % in IUHP 50–59 vs. 23.6 % in IUHP 60+, p = 0.041). In subsequent surveys, the need for making suggestions or queries on diagnosis and treatment to a doctor, as a result of researching online information, had diminished, and citizens aged 50+ in 2012 discussed information obtained from the Internet with their doctors significantly less frequently than in previous years (57.2 % of respondents in 2005, 52.1 % in 2007, and 39.2 % in 2012, respectively, p = 0.024). Similarly, in 2012, older citizens had significantly more frequent feelings of anxiety caused by using the Internet than in 2005 and 2007 (30.4 % of respondents in 2005, 21.9 % in 2007, and 36.8 % in 2012, respectively, p = 0.039) (Table 3).

3.4 Factors Affecting the Attitudes and Behavior of Citizens 50+ Using the Internet for Health Purposes

Multivariate analysis of different factors influencing the attitudes and behavior of citizens aged 50 and over using the Internet for health related purposes was conducted, see Table 4, part 1 and 2. As regards sex, women reported significantly more feelings of anxiety (p = 0.016); as regards education, a low level of education was more frequently related to feelings of reassurance or relief (p = 0.028), and higher education with more frequent suggestions or queries on diagnosis or treatment to the doctor (p = 0.05). Citizens aged 50 years and over, living in rural areas, and suffering from chronic diseases or disability, had feelings of anxiety caused by Internet use significantly more often. The least common anxiety was found in people from smaller towns and with no chronic diseases/disability (p = 0.044 and p = 0.024, respectively). Furthermore, a higher frequency of visits to the doctors was related to more frequent changes of use of medicines without consulting a physician or other health professionals (p = 0.043). As would be expected, mobile phone use was significantly associated with reduced fear concerning confidentiality of contact via the Internet (p = 0.009). The relationship between older age and worries about confidentiality, together with a lack of feeling of anxiety, has not been confirmed. There were no significant factors affecting a willingness to change life-style habits, and making, canceling or changing appointment with a doctor. No significant associations were found between the attitudes and behavior of citizens 50+ and other variables, such as employment status, type of residency and subjective assessment of health status.

4 Discussion

Patient use of Internet-acquired health information continues to grow (Pew Internet 2014; Wald et al. 2007; Krane Harris Poll 2006). The study performed by Murray et al. (2003) showed that 85 % of physicians had experienced a situation when a patient had brought information obtained via the Internet on a visit; 59 % of them stated that approximately up to one fifth of their patients had done this. The majority of health-related Internet searches by patients are for specific medical conditions and affect an encounter with a doctor. They are carried out by patients for different purposes: (1) before the medical appointment to find information on how to manage their own healthcare independently or decide whether to consult a health professional; (2) to find health information prior to an appointment to be prepared for a medical consultation; and (3) to find information after an appointment with a health professional to assess the consultation, to get a ‘second opinion’, to be reassured or to expand information received from the doctor (Santana et al. 2011; Wald et al. 2007; Akerkar and Bichile 2004; Ziebland et al. 2004). In our study, more than 70 % of citizens 50+, using the Internet for health purposes, had researched health information that could help them decide whether to consult a health professional, more than half used the Internet to gather health information before a medical encounter, and 64 % had searched for health information to assess the outcome of a medical consultation and obtain a ‘second opinion’. Similar, but somewhat lower, results were found by other authors (Andreassen et al. 2007; Krane Harris Poll 2006). According to a Harris Poll, 45–52 % of ‘cyberchondriacs’ had searched for health information based on a discussion with a doctor in 2005–2006 (Krane Harris Poll 2006). In turn, Rainie and Fox (2000) reported that 61 % of Internet users who sought medical information for themselves, and 73 % of those who sought information for others, turned to Web resources in connection with a visit to the doctor: 55 % of online ‘health seekers’ gathered online information before a consultation (Akerkar and Bichile 2004; Fox and Rainie 2002), and 50 % were seeking a second opinion from another physician (Akerkar and Bichile 2004; Rainie and Fox 2000). In the present study, the younger group of those surveyed (50–59 years) used the Internet slightly more often for these purposes, and the number of people over 50 in 2012, who had looked online for health information to help deal with a consultation, had significantly increased compared with studies from 2005 to 2007.

Online health information can affect the attitude, emotions, and health behaviors of older Polish citizens in different ways. Using the Internet for health purposes may result in triggering both negative and positive emotions. There is little research specifically exploring emotions that Internet users exhibit during the search process. Web-based patient information may serve to augment the information provided by doctors, and supplemental web information post-visit may help patients feel reassured, more comfortable, and satisfied with the medical consultation and treatment decision (Wald et al. 2007). In spite of its many advantages, the quality of Internet information is highly variable, and health information on the Web may be misleading or misinterpreted by the patients, inducing anxiety and resulting in inappropriate health decisions (Wald et al. 2007; Mc Caw et al. 2007). A few studies have also raised concerns regarding negative emotions, such as increased depression, fear, anxiety, worry and tension after being exposed to online health information (Gadahad et al. 2013). In our study, feelings of reassurance or relief after obtaining information on health or illness were reported by a similar number of respondents as feelings of anxiety and fear. Among different factors influencing attitudes and behaviors of citizens 50+ using the Internet for health purposes, significantly more feelings of anxiety were reported by women, persons living in rural areas and those suffering from chronic diseases or disability. Analyzing the subsequent surveys, older citizens in 2012 were significantly more frequently afflicted by anxiety caused by using the Internet than citizens in 2005 and 2007, which raises our concern and requires further in-depth observation. The European study of the use of e-health services by citizens, conducted in 2005, showed that it was twice as common for users to feel reassured after accessing the Internet for health purposes as it was to experience anxiety (Andreassen et al. 2007). However, in the Harris Poll in 2006, the percentage of those who indicated that online medical information was ‘very reliable’ had declined substantially from 37 % in 2005, to 25 % in 2006 (Krane Harris Poll 2006). This also raises anxiety and shows how important an issue the credibility of websites and up-to-date information is.

Willingness to change diet or other life-style habits, or making suggestions or queries on diagnosis or treatment to a doctor, were the most likely effects of health-related use of the Internet. According to the Pew Internet Health Report (Fox and Rainie 2002), 65 % of online health researchers has looked for information concerning nutrition, exercise or weight control. It is such material, as well as information concerning diseases and facts about prescription drugs, which topped the list of their interests (Wald et al. 2007). Our study revealed that almost half of all 50+ citizens were ready for a change of diet or other life-style habits, based on information they had found on the Web. These results were somewhat higher than those of other researchers; Campbell and Nolfi (2005) reported that 39 % of elderly adults were willing to change the way they eat or exercise, as were 33 % of adult Internet users reported by Andreassen et al. (2007). ‘Cyberchondriacs’ are also found to be using the Internet to assist them in their discussion with their physicians. The Harris Poll found that patients who searched the Internet for health information were more likely to ask more specific and informed questions of their doctors and to comply with recommended treatment plans (Harris Interactive 2001). On the other hand, Ferguson had already reported in 1998 that a third or more of patients were asking their physicians about health information they had found on the Internet, requesting them to recommend the best websites for their conditions, and asking for their e-mail addresses (Ferguson 1998). Various studies report that 28–55 % of those who looked for Internet health information had had a discussion concerning the information with their doctors (Ressi 2011; Bylund et al. 2007; Akerkar and Bichile 2004; Rainie and Fox 2000). Compared to those who did not discuss their Internet health information, those who did have poorer health and rate the quality of information higher (Santana et al. 2011; Bylund et al. 2007). Similar results were obtained in our study, with 46 % of older citizens making suggestions or queries on diagnosis or treatment to a doctor on the basis of information found on the Internet. However, a relationship with health status was not confirmed, and the only significant factor was a high level of education, which positively correlated with the need for discussion with a physician. A worrying phenomenon is, however, the gradual decrease in the need for a conversation with a doctor in subsequent surveys, which was also observed by Krane (Harris Poll 2006).

As was mentioned earlier, the ‘e-revolution’ has caused a shifting of power within the health care relationship, and e-patients ‘empowered’ with Web information are much more likely to make decisions and take responsibility for their own health. Many e-patients believe that the medical information and guidance they can find online is more complete and useful than the expertise they receive from their doctors (Ferguson 2004). On the other hand, some physicians may feel that patients are challenging their authority during the visit and experience conflict with more assertive patients (Murray et al. 2003). Moreover, some studies report that online health information negatively influences users’ healthcare decisions as wrong self-diagnosis, resulting in their engaging in treatment options inconsistent with professional recommendations and buying over-the-counter drugs (Gadahad et al. 2013). In our study, more than 20 % of citizens aged 50+ decided to make, change, or cancel an appointment with a doctor as a result of researching online health information, and almost 8 % took a critical decision to change their use of medicines without consulting their family doctor, specialist, or any other health professionals. Comparing the outcomes with the European survey reported by Andreassen et al. (2007) (9 % and 4 %, respectively), our results are higher, and older citizens proved to be less reliant on their providers to make decisions concerning their care. This has also been observed by other researchers (Ressi 2011; Akerkar and Bichile 2004; Rainie and Fox 2000). It is also interesting to note that the only factor significantly related to a more frequent change of use of medicines without consulting a physician or other health professionals, was higher frequency of visits to the doctors. This seems to indicate that patients regularly visiting their physicians are more willing to make independent decisions concerning their health.

5 Conclusions

The Internet has profoundly changed the way patients search for health information. The attitudes, emotions and health behaviors of citizens have all been affected in different ways by information derived via the Web. Physicians should be aware of how much influence the Internet and online health information has had on their patients and the resulting risks and benefits. On the one hand, the Internet can empower patients and increase their sense of control over disease by providing patients with the knowledge and self-awareness necessary to make informed decisions about their health and improve the quality of their lives. On the other hand, depending on the source, health information on the web may be misleading or misinterpreted, influencing patients’ health behaviors and health outcomes, triggering patient anxiety and other negative emotions, and even resulting in their taking inappropriate decisions with regard to their health or illness.

References

Akerkar SM, Bichile LS (2004) Doctor-patient relationship: changing dynamics in the information age. J Postgrad Med 50(2):120–122

Andreassen HK, Bujnowska-Fedak MM, Chronaki CE, Dumitru RC, Pudule I, Santana S, Voss H, Wynn R (2007) European citizens’ use of e-health services: a study of seven countries. BMC Public Health 7(1):53

Bylund CL, Gueguen JA, Sabee CM, Imes RS, Li Y, Sanford AA (2007) Provider-patient dialogue about Internet health information: an exploration of strategies to improve the provider-patient relationship. Patient Educ Counc 66:346–352

Campbell RJ, Nolfi DA (2005) Teaching elderly adults to use the Internet to access health care information: before-after study. J Med Internet Res 7(2):e19

Ferguson T (1998) Digital doctoring: opportunities and challenged in electronic patient-physician communication. JAMA 280:1261–1262

Ferguson T (2000) Online patient-helpers and physicians working together: a new partnership for high quality health care. BMJ 321:1129–1132

Ferguson T (2004) The first generation of e-patients. These new medical colleagues could provide sustainable healthcare solutions. BMJ 328:1148–1149

Fox S, Rainie L (2002) Vital decisions: a pew internet health report. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2002/05/22/vital-decisions-a-pew-internet-health-report/. Accessed on 7 November 2014

Gadahad PR, Theng J-L, Sin Sie Ching J, Pang N (2013) Web searching for health information: an observational study to explore users’ emotions. Hum Comput Interact Appl Serv 8005:181–188

Grant P (2010) Consumer health trends. Healthcare engagement in a digital world. Creationhealthcare. Available from: http://www.slideshare.net/paulgrant/consumer-health-trends. Accessed on 7 Nov 2014

Hoch D, Ferguson T (2005) What I've Learned from E-Patients. PLoS Med 2(8): e206. Available from:http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020206. Accessed on 8 Nov 2014

Houston TK, Allison JJ (2002) Users of Internet health information: difference by health status. J Med Internet Res 4:e7

Interactive H (2001) The increasing influence of eHealth on consumer behavior. Health Care News 1:1–9

Krane D (2006) The Harris poll. Harris Interactive. Available from: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/harris-poll-shows-number-of-cyberchondriacs---adults-who-have-ever-gone-online-for-health-information---increases-to-an-estimated-136-million-nationwide-5580 8632.html. Accessed on 6 Nov 2014

Kummervold PE, Chronaki CE, Lausen B, Prokosch HU, Rasmussen J, Santana S, Staniszewski A, Wangberg SC (2008) E-Health trends in Europe 2005–2007: a population-based survey. J Med Internet Res 10(4):e42

Malone M, Haris R, Hooker R, Tucker T, Tanna T, Honnor S (2004) Health and the Internet – changing boundaries in primary care. Fam Pract 21(2):189–191

McCaw B, McGlade K, McElnay J (2007) The influence of the internet on the practice of general practitioners and community pharmacists in Northern Ireland. Inform Prim Care 15(4):213–217

Murray E, Lo B, Pollack L, Donelan K, Catania J, Lee K, Zapert K, Turner R (2003) The influence of health information on the Internet on health care and the physician-patient relationship: national U.S. survey among 1.050 U.S. physicians. J Med Internet Res 5(3):e 17

Pew Research Internet Project (2014) Pew internet: health fact sheet. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/health-fact-sheet/. Accessed on 6 Nov 2014

Rainie L, Fox S (2000) The online health care revolution. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2000/11/26/the-online-health-care-revolution/. Accessed on 7 Nov 2014

Ressi M (2011) Today’s empowered consumer: the state of digital health in 2011. Manhattan Research 2011. Available from: https://kelley.iu.edu/CBLS/files/conferences/Ressi - Indiana University.pdf. Accessed on 6 Nov 2014

Santana S, Lausen B, Bujnowska-Fedak M, Chronaki CE, Prokosh H-U, Wynn R (2011) Informed citizen and empowered citizen in health: results from an European survey. BMC Fam Pract 12:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-20

Seybert H (2012) Internet use in households and by individuals in 2011. EUROSTAT. Industry, trade and services. Statistics in focus. Available from: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-SF-12-050/EN/KS-SF-12-050-EN.PDF. Accessed on 6 Nov 2014

The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation Survey Report (2004) E-Health and the elderly: how seniors use the internet for health – survey. Available from: http://kff.org/medicare/poll-finding/e-HealthE-Health-and-the-elderly-how-seniors-2/. Accessed on 7 Nov 2014

van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CHC, Taal E, Smit WM, Moens HJB, Siesling S, Seydel ER, van de Laar MAFJ (2009) Health-related Internet use by patients with somatic diseases: frequency of use and characteristics of users. Inform Health Soc Care 34:18–29

Wald HS, Dube CE, Anthony DC (2007) Untangling the Web – the influence of Internet use on health care and the physician-patient relationship. Patient Educ Counc 68(3):218–224

Ziebland S, Chapple A, Dumelow C, Evans J, Prinjha S, Rozmovits L (2004) How the internet affects patients’ experience of cancer: a qualitative study. BMJ 328(7439):564

Acknowledgements

This article forms a part of national surveys on the use of the Internet and e-health services in Poland; the surveys in 2005 and 2007 were conducted within WHO/European project on e-health consumer trends. The authors would like to thank Tomasz Kujawa and Marcin Opęchowski for their methodological and statistical help.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no interests, financial or otherwise, that might lead to a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bujnowska-Fedak, M.M., Kurpas, D. (2015). The Influence of Online Health Information on the Attitude and Behavior of People Aged 50+. In: Pokorski, M. (eds) Respiratory Health. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology(), vol 861. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/5584_2015_130

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/5584_2015_130

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-18792-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-18793-8

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)