Abstract

Objective

To present the major causes, diagnosis, indications, and basic principles of surgical treatment of vesico-vaginal fistulas (VVF).

Methods

From 1978 to 2004, 235 surgical procedures in 220 women with vesico-vaginal fistulas were performed at the Clinical Center of Serbia, Urological Clinic, due to primary or recurrent VVF. There were 220 primary procedures: 129 transvesical approaches (TVES), 59 transvaginal repairs (TVAG), and 32 transperitoneal approaches with flap interposition (TPA). Transvesical approach was the most common procedure in the early period (1978–1993) and less frequent in the late period (1994–2004). The main causes of VVF were hysterectomy for benign conditions (62.7%), hysterectomy for malignant conditions (30.4%), cesarean section (5.9%), and obstetric injuries (0.9%).

Results

There was no perioperative mortality. There were fifteen recurrent fistula formations: twelve after the first operation and three after the second. The recurrence rates between the procedures were comparable: TVES 6.6%, TVAG 6.4%, and TPA 5.4%.

Conclusions

The total recurrence rate of 6.4% did not differ significantly between various procedures. However, TVAG is less invasive and suitable for uncomplicated cases, whereas TPA should be recommended for great and recurrent VVF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Vesico-vaginal fistulas (VVF) are the most common urogenital fistulas; they are usually the consequence of obstetric, surgical, or radiation injury of the urogenital tract. Early in the past century, the most common cause of the VVF was complicated childbirth with tissue injury. With modern obstetric services, these fistulas are rare, and the most common cause, 75–90% of all VVF, is total abdominal hysterectomy [1, 2]. The second most common cause of VVF is malignant infiltration of various pelvic cancers, for example cervical, vaginal, endometrial, bladder, and rectal cancer. Nowadays, a significant number of VVF are the consequence of radiation therapy of pelvic tumors. These fistulas may appear late, even 20 years after the initial radiation therapy [3]. Surgical injury during various pelvic procedures is the cause of VVF in 0.5–2.0% [4]. About 10–15% of patients with VVF have coexistent ureteric injury [5]. In developing countries, the most common causes of VVF are complications of neglected, prolonged, or obstructed childbirth [6]. The main symptom of VVF is urinary leakage from the vagina. The diagnosis is usually completed after cystoscopy combined with vaginal examination.

The general principles of surgical management are to close, separately, both openings of the fistula, with interposition of the tissue flap. The ideal time for operative repair is 8–12 weeks after fistula formation or failed repair.

Methods

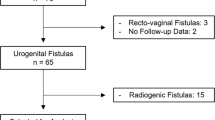

From 1978 to 2004, 235 surgical procedures in 220 women with vesico-vaginal fistulas were performed in the Clinical Center of Serbia, Urological Clinic, for cure of primary or recurrent VVF.

The main causes of VVF were hysterectomy for benign conditions (62.7%), hysterectomy for malignant conditions (30.4%), cesarean section (5.9%), and obstetric injuries (0.9%) (Table 1).

There were 220 primary procedures: 129 transvesical approaches (TVES), 59 transvaginal repairs (TVAG), and 32 transperitoneal approaches with flap interposition (TPA). Transvesical approach was the most common procedure in the early period (1978–1993) and less frequent in the late period (1994–2004).

Seventy patients had small fistula (<10 mm), 104 patients had medium sized fistula (10–20 mm), and 46 women had large fistulas, greater than 20 mm (Table 2).

Supratrigonal fistula was found at 152 patients (69.1%) and trigonal fistula was present at 68 patients (30.9%). Because of the proximity of the fistula to ureteral orifices, ureterocystoneostomy (UCN) was performed in nine women, in two cases bilateral.

Operative technique

Technical details are common for all approaches and they include excision of the diseased tissue in the bladder and vagina, separation of the bladder from the vagina with a margin of healthy tissue, and watertight closure of both bladder and vagina without tension. In the transvesical approach, cystostomy is performed using the extraperitoneal approach. After excision of the walls of the fistula, interrupted vycril-0 sutures are placed on the vaginal wall and, after that, perpendicularly on the bladder wall. The same technique is performed in transvaginal repair, with the opposite approach. In the transperitoneal approach, a midline incision is made along the posterior bladder wall, to the fistula opening. After excision of the fistula, interrupted vycril-0 sutures are placed in the manner similar to that in transvesical repair. The flap is then interposed between bladder and vagina and secured on the bladder wall. The omental flap was used as the first choice if it was of sufficient length; otherwise, a peritoneal flap was created. (In this series, the omental flap was used in 14 cases, and a peritoneal flap in 18 primary repairs and five recurrent cases.) The posterior bladder wall is closed using a running vycril-1-0 suture. Both urethral catheter and suprapubic tube were used in all patients.

Results

There was no perioperative mortality. The mean patients’ age was 56 years (29–72 years).

There were 12 recurrent fistulas after 220 primary procedures, or 5.4%. There were no significant differences between three procedures, i.e. TVES, TVAG, and TPA, with recurrence of 5.4%, 5.1%, and 6.2%, respectively.

There were nine cases of recurrence in supratrigonally located fistulas (9/152, or 5.9%) and three cases in trigonal fistulas (3/68, or 4.4%).

There were three recurrent fistulas after twelve secondary procedures, which were managed successfully using flap procedures.

Finally, total recurrence was 15/235 or 6.4% and did not differ significantly between three procedures (TVES 6.6%, TVAG 6.4%, and TPA 5.4%) (Table 3).

Except for recurrence of the fistula, the major complication was wound infection, which occurred in sixteen women, or 7.3%. Twenty-one women had transient urinary incontinence, which ceased spontaneously.

Discussion

Vesico-vaginal fistulas (VVF) are the most common female genitourinary fistulas, and also the most common acquired fistulas of the urinary tract. They emerge as a complication of gynecological surgery in developed countries, or obstetric trauma in third-world countries. Obstetric fistulas are usually larger than post-hysterectomy fistulas and located more distally [1, 6].

The main symptom of VVF is leakage of urine from the vagina, apparent only when the bladder is full, or constantly in the presence of great fistula. After gynecological surgery, leakage usually appears after removal of the urinary catheter [7]. Important clinical details of VVF are the size and the localization of the fistula, its relationship with ureteral orifices, and the presence of inflammation and scar tissue around the fistula.

Cystoscopy with vaginal examination is the most important clinical examination in the evaluation of VVF. The instillation of methylene-blue solution into the bladder is helpful in the diagnosis of small fistulas. Intravenous urography with cystography in the lateral position is necessary to discover the position of the fistulous channel and to exclude ureterovaginal fistula.

Minimally invasive treatment can be tried only in women with fistulas smaller than 5 mm. Prolonged catheterization, with or without electro-coagulation, was successful in three of 151 cases [8]. Moreover, there were three successful cases of closing VVF with fibrin sealing [9].

Surgical treatment is mandatory in the treatment of VVF. Early fistula repair is often followed by the relapse because of tissue necrosis; early surgery is indicated only in intraoperatively discovered fistulas. The optimum moment for surgery is after completion of the healing reaction i.e. 2–3 months, after the appearance of the fistula. Important technical details include excision of all diseased tissue in the bladder and vagina, complete separation of the bladder from vagina with a margin of healthy tissue, and watertight closure of both bladder and vagina without tension. Interposition of vascularized tissue (peritoneum, omentum, labial fat pad, gracilis muscle, myocutaneous muscle flaps) between the closed bladder and the vagina is recommended to improve vascularity [10, 11]. Moreover, these tissues are capable of absorbing urinary extravasate and preventing the leakage from the bladder.

The approach is dependent of many factors and on the experience and training of the surgeon. The approaches most often used are vaginal, transvesical, and transperitoneal, as described by Chapple and Turner-Warwick [12], or, recently, laparoscopic.

Abdominal approach may be used to treat all types of VVF; it is the preferred approach in complex situations, when the fistula is large (wider than 4 cm), or when ureteral orifices are involved in the fistula and ureteral reimplantation is required. The success rate is 80–90% [13–16]. Interposition of well-vascularized omental or peritoneal flaps between the bladder and the uterus is recommended for prevention of relapse and for treatment of giant VVF, i.e. wider than 5 cm [17]. Vaginal approach is less aggressive and well accepted by patients. It involves tension-free closure of the fistula with creation of an anterior vaginal wall flap and is followed with high success rate, up to 96% [18]. Interposition of vascularized grafts can also be performed by this approach; the success rate is 82–97% [2, 19, 20].

In our series, the success rate was 94.6% after the primary procedure, 75% after the secondary procedure, and the total rate was 93.6%. In addition, there were similar success rates for the three procedures (TVES, TVAG, and TPA).

However, it is difficult to compare success rates for each procedure, because of differences between indications (size and the location of the fistula, co-morbidity), different surgeons, and surgical preference. Moreover, the transvesical approach was the most popular approach in the early period of this study. Finally, we recommend the vaginal approach in non-complicated cases, and for small and distally located fistulas. The transvesical approach is rarely required today, and is used only in complex cases, with great fistulas, and in situations in which an additional surgical procedure, for example ureterocystoneostomy, is required. However, the transperitoneal approach with use of tissue flaps is the most secure technique for treatment of complex cases, giant, and, especially, recurrent fistulas.

References

Haferkamp A, Wagener N, Buse S, Reitz A, Pfitzenmaier J, Hallscheidt P et al (2005) Vesicovaginal fistulas. Urologe A 44(3):270–276. doi:10.1007/s00120-005-0766-z

Eilber KS, Kavaler E, Rodriguez LV, Rosenblum N, Raz S (2003) Ten-year experience with transvaginal vesicovaginal fistula repair using tissue interposition. J Urol 169(3):1033–1036. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000049723.57485.e7

Graham JB (1965) Vaginal fistulas following radiotherapy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 120:1019–1030

Mattingly RF (1978) Acute operative injury to the urinary tract. Clin Obstet Gynecol 5:123–149

Goodwin WE, Scardino TT (1980) Vesicovaginal and ureterovaginal fistulas: summary of 25 years of experience. J Urol 123:370–374

Williams G (2007) The Addis Ababa fistula hospital: an holistic approach to the management of patients with vesicovaginal fistulae. Surgeon 5(1):54–57

Woo HH, Rosario DJ, Chapple SR (1996) The treatment of vesicovaginal fistulae. Eur Urol 29:19

Pancer NL (1980) The post total hysterectomy (vault) vesicovaginal fistula. J Urol 123:839–840

Welp T, Bauer O, Diedrich K (1996) Use of fibrin glue in vesico-vaginal fistulas after gynecologic treatment. Zentralbl Gynakol 118(7):430–432

Punekar SV, Buch DN, Soni AB, Swami G, Rao SR, Kinne JS et al (1999) Martius’ labial fat pad interposition and its modification in complex lower urinary fistulae. J Postgrad Med 45:69–73

Horch RE, Gitsch G, Schultze-Seemann W (2002) Bilateral pedicled myocutaneous vertical rectus abdominus muscle flaps to close vesicovaginal and pouch-vaginal fistulas with simultaneous vaginal and perineal reconstruction in irradiated pelvic wounds. Urology 60(3):502–507. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(02)01823-X

Chapple C, Turner-Warwick R (2005) Vesico-vaginal fistula. BJU Int 95(1):193–214. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.04531.x

Khan RM, Raza N, Jehanzaib M, Sultana R (2005) Vesicovaginal fistula: an experience of 30 cases at Ayub Teaching Hospital Abbottabad. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 17(3):48–50

Wein AJ, Malloy TR, Carpiniello VL, Greenberg SH, Murphy JJ (1980) Repair of vesicovaginal fistula by a suprapubic transvesical approach. Surg Gynecol Obstet 150(1):57–60

Pinter J, Feher M, Szokoly V, Varga A (1988) Transvesical and transabdominal closure of vesicovaginal fistulas. Acta Chir Hung 29(2):143–149

Husain A, Johnson K, Glowacki CA, Osias J, Wheeless CR Jr, Asrat K et al (2005) Surgical management of complex obstetric fistula in Eritrea. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 14(9):839–844. doi:10.1089/jwh.2005.14.839

Bissada NK, McDonald D (1983) Management of giant vesicovaginal and vesicourethrovaginal fistulas. J Urol 130(6):1073–1075

Catanzaro F, Pizzoccaro M, Cappellano F, Catanzaro M, Ciotti G, Giollo A (2005) Vaginal repair of vesico-vaginal fistulas: our experience. Arch Ital Urol Androl 77(4):224–225

Cortesse A, Colau A (2004) Vesicovaginal fistula. Ann Urol (Paris) 38(2):52–66

Raz S, Bregg KJ, Nitti VW, Sussman E (1993) Transvaginal repair of vesicovaginal fistula using a peritoneal flap. J Urol 150(1):56–59

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hadzi-Djokic, J., Pejcic, T.P. & Acimovic, M. Vesico-vaginal fistula: report of 220 cases. Int Urol Nephrol 41, 299–302 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-008-9449-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-008-9449-1